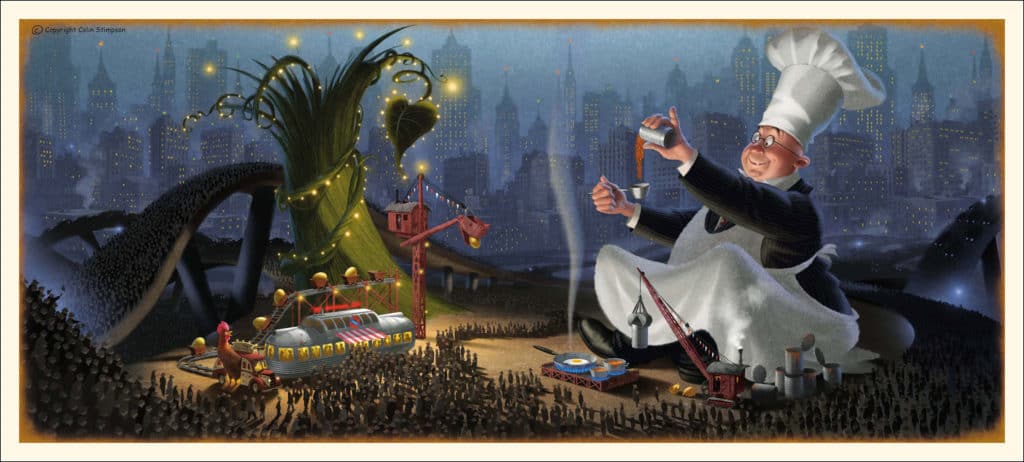

As you can see from the cover art, this picture book has been illustrated by someone with a lot of experience in digital art — as a coffee table book of illustrations this stands alone as an exhibition of beautiful colour, wonderfully composed perspective drawings and interesting character design.

The O.G. Jack And The Beanstalk is, at its heart, a male coming-of-age tale, in a milieu where boys must learn to be the income earners for the females in their family. You’ve probably also heard theories about what the beanstalk symbolises. I think that’s a bit of a stretch.

CRITIQUE OF CAPITALISM

As a story for older readers, this modern retelling would be good for discussing ideas such as industrialisation and its impact on small vendors, the problems with large fast food companies and a capitalist economy.

Normally in stories like these, the ‘giant’ stands for ‘the corporation’. Is that what the giant stands for here? If so, would the world really run better if these corporations suddenly quashed the structures they’ve worked to build?

The ideology of the original tale is a bit dodgy actually, when you think about it: Modern picturebook writers don’t get away with glamorising thieves. Just take a look at the one-star reviews of This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen, which is a great story, but rubs some gatekeepers of children’s literature completely up the wrong way. I would add, in the case of the modern Klassen story, the thief is duly punished. (He — or she? — gets eaten.) Not so in the original Jack and the Beanstalk. Jack is richly rewarded for his thievery and daring.

In Stimpson’s modern retelling, however, the setting is different and so must be the ideology. What do you think of when you think ‘capitalism’? Those in favour of capitalism probably conjure up a (traditionally) picture book township, with a milk bar, a greengrocer, a picture theatre and butcher on each side of main street. The butcher who sells better sausages ends up making more money and eventually puts the inferior butcher out of business. Consumers win.

We’ve seen over the past centure or so that, actually, capitalism has a much darker side than that; in a capitalist society the rich can become super wealthy simply by having money in the first place, while the poor become increasingly destitute and are unable to work their way out of the pit.

What about the ideology in this book? This is no idealistic view of capitalism; it is a critique. The ‘little guy’ can easily get screwed over due to the machinations and schemings of people with far more money. This ‘flyover’ symbolises the way in which the super wealthy build their empires without a second thought to the little people, passing them over, so to speak. And in any narrative, the little people are the ‘underdogs‘. We love stories starring underdogs.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

Stimpson’s wonderful illustrations emphasise the similarity between the beanstalk and the flyover. Both are very high, thick structures wending and twisting high into the sky. There are other hints of beanstalk, too, foreshadowing what’s to come. Take a closer look at this wooden pole below, with the electrical cabling wound around it; this city hasn’t completely given itself over to industrialism — vestiges of the more wholesome natural world remain.

The bright green of the beanstalk contrasts beautifully against the monochromatic, drab and rainy city.

STORY STRUCTURE

The story structure is interesting. It’s only after looking closely I realise that Jack and The Giant share the character arc, which suggests that — symbolically, at least — Jack and The Giant are the same. By ‘one and the same’ I mean that Jack starts off the story with a shortcoming and desire, but it’s the giant who has the anagnorisis. They both share the new situation, along with the mother. Fairytales often go by a number of different titles and this one is no different, sometimes known as Jack and the Giant Man, which underscores my theory, don’t you think?

What might be the reason for uniting Jack and The Giant like this? Ultimately, this is a fantasy revenge tale. If only the little guy could crush the big corporations with a bit of magic.

Our hero Jack also has a trusty dog called Bella, but apart from just being there, Bella plays no huge role in the story. I do wonder if the inclusion of a dog with a specifically female name serves a political purpose, though; to ameliorate the depiction of the only human female — the mother, who is almost always portrayed in Jack and the Beanstalk retellings as awful.

WEAKNESS

Jack and his mother run a very small food truck type business in a down-and-out looking part of the city. When a new overpass is built right over their food truck, they no longer have a living income. The engine of this truck broke down a long time ago, as explained on the first page. This lampshades that particular plot problem: Normally food trucks can go elsewhere but these two are stuck in this spot.

DESIRE

Jack wants to have enough money for his mother and himself and also wants to be a man. Being a man involves going out in the world, contrasted with what it is to be a woman, which is staying in the home. Although the mother tells him to go to the shops and buy coffee and milk, he finds some manly autonomy on the road. When the travelling salesman with the magic baked beans convinces him to buy them, this is possibly the first time he’s ever disobeyed his mother.

Readers of the original tale would have been immediately suspect of this travelling salesman, renowned sellers of snake oil, travelling from town to town for the express purpose of running from their bad reputation. But a modern audience knows that this particular travelling salesman is legit.

OPPONENT

The mother in this modern retelling is basically the same character as the mother in the original; she doesn’t ‘beat’ him, but she definitely yells at him and tries to cut him back down to size. The mother is the human opponent. Compared to Jack she is massive. Her size is emphasised when she stands at the door of their caravan, hands on hips, standing above Jack. Since the giant in this tale is benign, the mother becomes the giant.

It’s a very common storytelling technique — pitting a main male character against a woman in his own family to make the audience feel sorry for him. You can see in many modern stories, for example in the pilot episode of Breaking Bad, where Walt is painted very much as an underdog character, ‘pussy whipped’ by his wife. (Vince Gilligan put cries of sexism back upon the audience, but look closely at the pilot and tell me again how it wasn’t of his very own making.)

There is also a non-human opponent in this tale — the unseen corporation who designed the overpass: Capitalism and progress at the expense of that specific kind of human-to-human interaction that occurs when a small restaurant cooks for its customers. This tale also has a very Michael Pollan view of food and cooking.

PLAN

The original plan — devised by the mother — is to sell coffee instead of run a fuller menu as before, but Jack’s plans change when he is convinced by the travelling baked bean man to buy his wares.

They change once again after the huge stalk grows. Now he’ll climb it.

BIG STRUGGLE

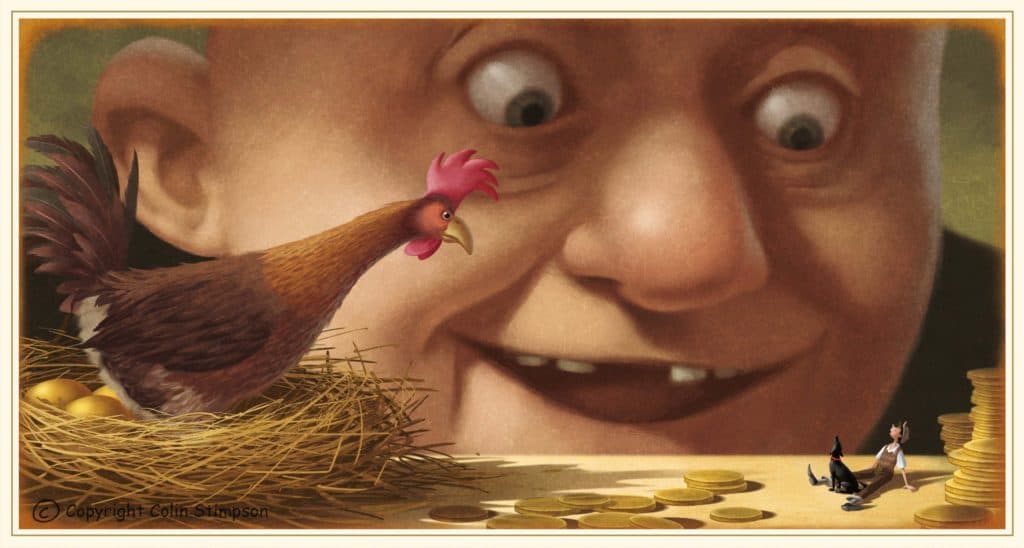

The giant in in this tale is not an opponent, which is where the ‘twist’ comes in. (It’s only a twist if you’ve read the original — and it’s assumed the young reader has.)

Instead, the giant is presented as a possible opponent, but it is revealed soon enough that he is in fact a secret ally, who has been waiting for someone to visit.

This friendly giant loves to cater for other people, but his immense riches have required lots of counting and he hasn’t, until Jack’s arrival, been able to fulfil this passion.

The giant uses his immense weight to crush the overpass.

ANAGNORISIS

It’s the giant who has the anagnorisis. If he stops focusing on his immense wealth, he can have the job he always wanted: working in a downtown cafe.

NEW SITUATION

The giant uses his wealth to build an excellent restaurant where the food truck once was. Jack, the Giant and the mother all work together, running their food business.