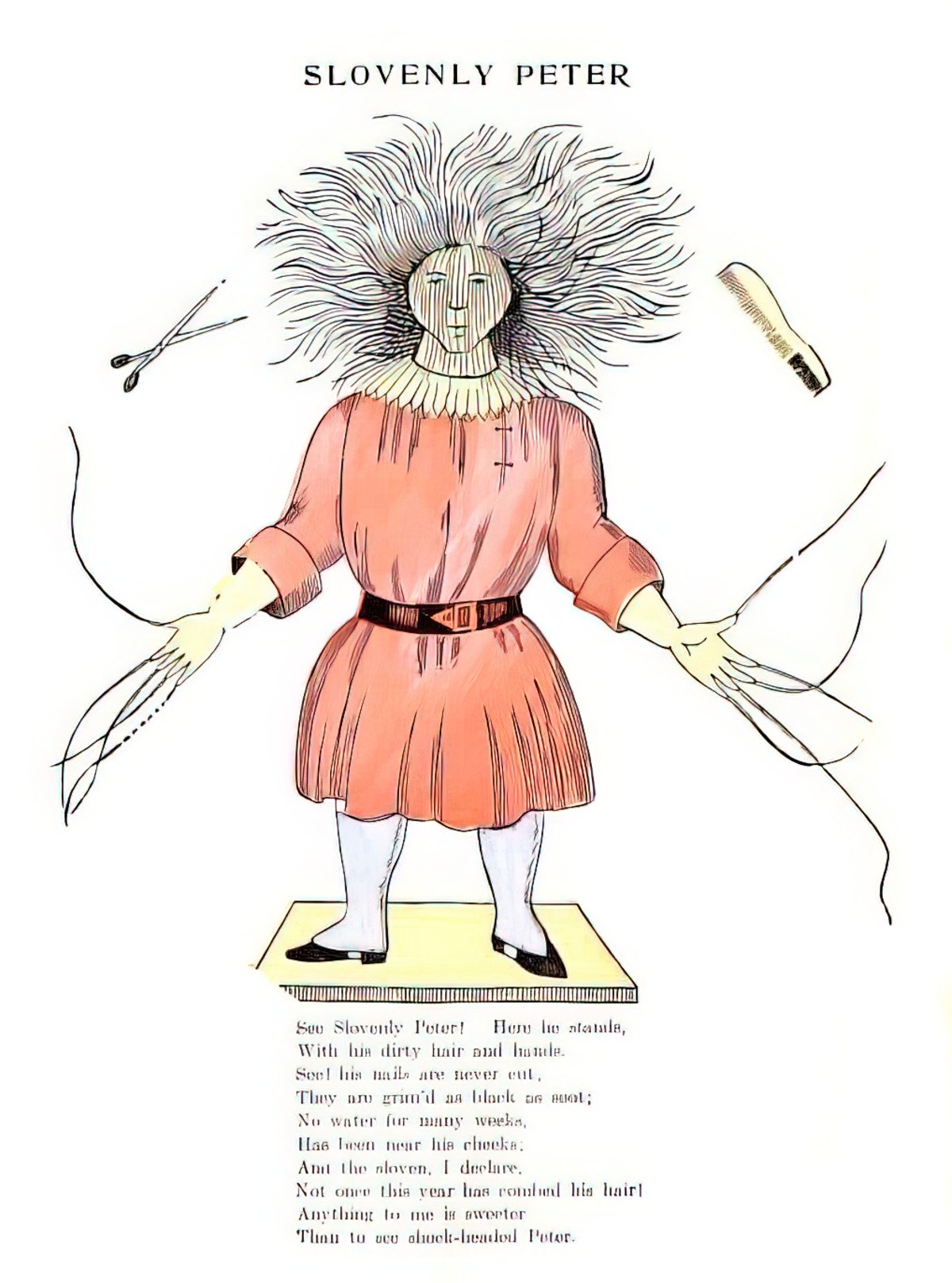

Harry The Dirty Dog (1956) is a good example of what Bakhtin termed ‘the material bodily principle‘ — the human body and its concerns with food and drink (commonly in hyperbolic forms of gluttony and deprivation), sexuality (usually displaced into questions of undress) and excretion (usually displaced into opportunities for getting dirty).

This book is also an example of an ‘interrogative text’ in which authority is questioned. The main, childlike character (which happens to be a somewhat anthropomorphised dog) runs away and has fun even though he is supposed to be having a bath.

There’s an entire category of stories about family members who are so dirty that, once cleaned up, even their own kin don’t recognise them.

| W115.3 | Rancher is not recognized by his wife and family after he has cleaned up in town at hotel. | U.S.: Baughman.NEVADA: Hart Sazerac 201, 1878. |

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STORY?

Harry is a dog who hates having a bath. One day, he hears the bath water running, assumes he is up for a bath, and decides to skip out on it. The story starts on the front endpapers.

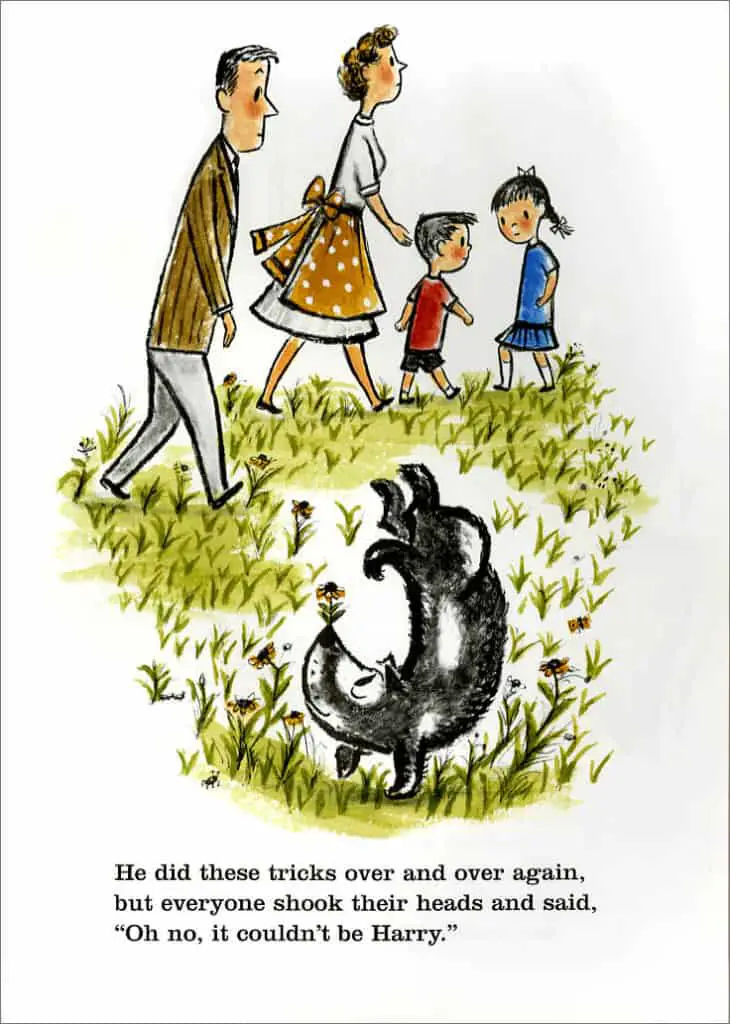

He takes the scrubbing brush, buries it in the backyard, then runs off into town. On his adventures he gets dirtier and dirtier, until he is unrecognisable. Eventually he gets hungry and must return home. But his family don’t recognise him and refuse to believe it’s him. He tries all sorts of familiar tricks, to no avail.

In order to prove that he is indeed a white dog with black spots (rather than the inverse) he gives himself a bath.

After that he is welcomed back into the family fold. He will never skip out on bathtime again, though we know he’s still not entirely happy about it. This time he’s hidden the scrubbing brush under his bed.

WONDERFULNESS

To a young audience, Harry is a very funny character. Many child readers don’t much like bathing and showering (‘won’t get in, won’t get out’), and will relate to Harry’s distaste for the bathroom.

The language avoids clunkiness while at the same time speaking across to children: ‘He played where they were fixing the street and got very dirty.’ An adult text would be more specific about what, exactly, the workmen are up to. But this is all we need to know. We see barrels of tar and street equipment. This page functions a bit like a look-and-learn page of a Richard Scarry book — there is so much going on in the double-page spread.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF HARRY THE DIRTY DOG

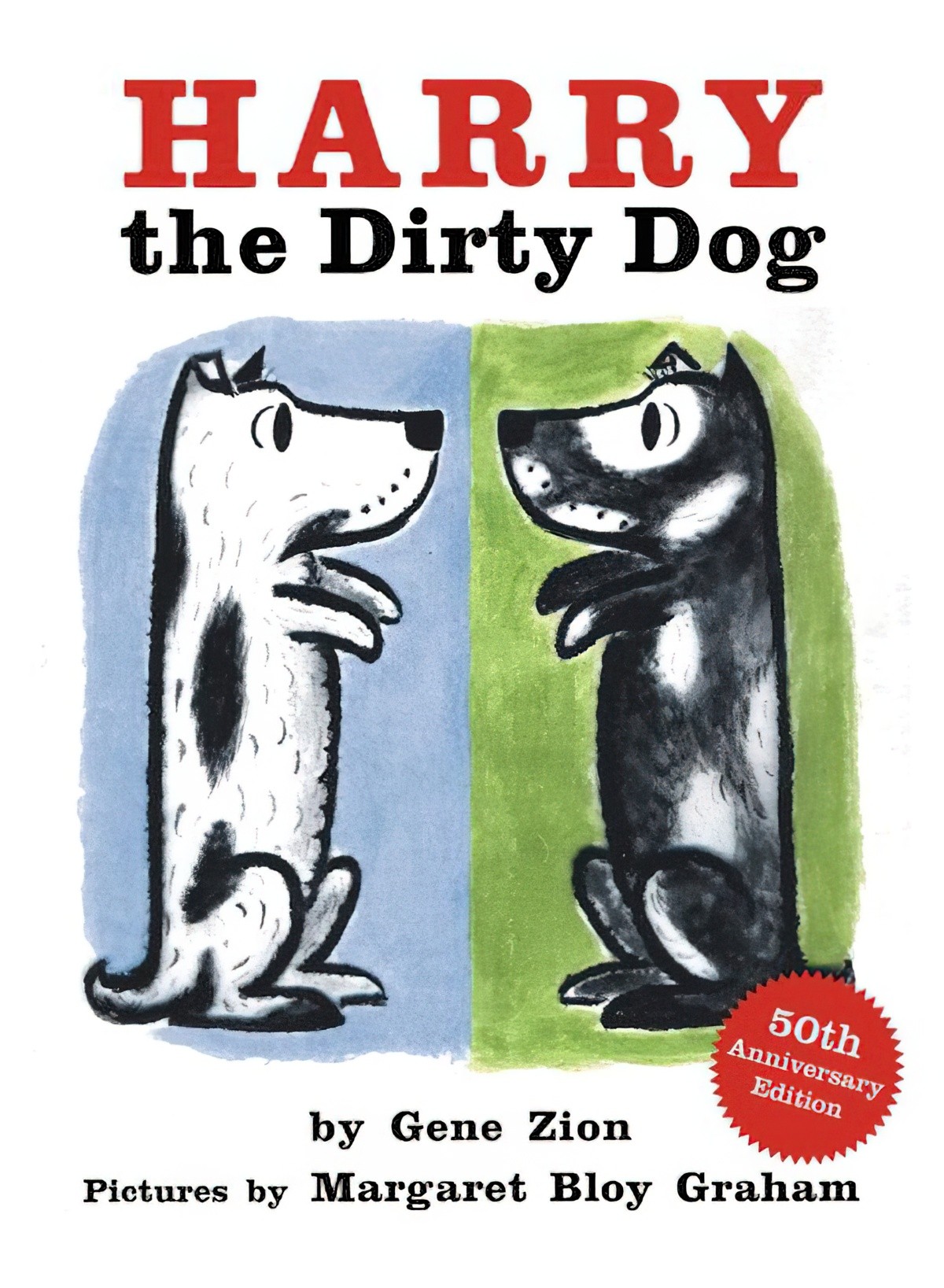

There are is a larger colour palette in this picturebook than on the subsequent book in this series, No Roses For Harry. The dominating colours are green, yellows and blues. But the distinctive ‘colour’ in these pictures is the use of sketchy black. The smudgy black outlines of the objects, complemented by the rough colouring-in of skies, floors and walls, lends a ‘dirty’ look to the illustrations, which naturally reflect the ‘dirtiness’ of the story itself.

When illustrating animals in picturebooks, in which they are most often personified/anthropomorphised to a certain degree, it’s often wise to forget some of what you know of animal anatomy, in favour of postures and gestures that look full of movement. On the first page we see Harry running down stairs with the scrubbing brush in his mouth, and behind him we see one of his hind legs kicked up in a position that you wouldn’t see in real life. Yet it is exactly this sort of artistic licence that gives Harry his personality.

On page two, Harry digs a hole and has his head inside it. We can’t see much of him. But the reader’s eye is lead straight to Harry because of the placement of three birds as audience — one in the tree, one in the foreground and one on the fence. Each bird is looking straight at Harry, and seem to be saying something to him. These birds are stand-in readers, direction our line of vision.

On page three, kittens and human passersby are given the same role, as Harry struts down the main street.

By the railroad page it’s clear that Harry is enjoying himself immensely. This is clear from the smiles on the people around him. Although to an adult mind each of these passersby each have their own independent emotions, unrelated to whatever a dog is getting up to, the fact that they are all smiling benevolently shows the child reader that Harry is having a lot of fun as he gets filthy dirty. There are no disapproving glares to be seen here.

Overleaf on the construction site, you may recognise a bit of visual humour that dates back to Peter Rabbit, as we see the front of one dog and the hind legs of another, different dog entering a piece of concrete pipe. This almost looks as if one very long dog is running through the pipe. Also on this page, notice the way the sun has been drawn, in true childlike fashion, with sun rays emanating out from a yellow circle, in the same way children tend to depict the sun.

The expressions of the passersby have started to become more alarmed on the following page, after Harry turns into a very dirty dog. The young reader should sense impending doom… (The children, however, are delighted.)

Since separation from the family is a child’s biggest fear, young readers will naturally empathise with Harry when he starts to wonder if his family thinks he’s gone for good. The sight of people inside the restaurant eating only serve to remind Harry and the readers that if he doesn’t hurry on home he’ll go without his basic needs met. The intratext of ‘No Dogs’ on the sign reminds readers that although Harry is humanlike, the human world is nonetheless closed to a dog. He has no choice but to hurry on home.

Harry is in classic ‘shamed dog’ position after crawling in the back door. A large letter H on the roof of the kennel tells us unambiguously that this is Harry’s kennel. He’s almost back to safety. One bird chirps at him from the tree. Like the reader, this bird is somewhat ‘in the know’.

Then we have the dramatic irony that children love — they love to know something that characters in a story have not worked out yet. We know where Harry is, but the family simply cannot find him. Next we have the rule of threes, with three pages of Harry doing various tricks to prove who he is. Then, the family walk away. Oh no!

Almost defeated, he thinks of giving up. This is the classic hero’s journey. Suddenly he thinks of a solution — he remembers where he has buried his scrubbing brush!

The entire family watches in delight as Harry gives himself a bath and turns back into Harry. The era of this book comes to the fore when we see the mother wearing an apron. It’s the mother who holds the mop, and who is obviously going to clean up this bubbly bathroom mess afterwards. That said, not all that much has changed when it comes to gender roles in modern picture books.

The final page offers an easter egg, and young readers will feel smart when they notice the scrubbing brush sticking out from under his cushion. This is also called a ‘wink‘.

The nice thing about this brush is that Harry has had a character arc — he is no longer 100% against baths, but nor has he had an unrealistic complete turnabout in character — he’ll put up with baths but only if necessary.

STORY SPECS OF HARRY THE DIRTY DOG

Between 28 and 32pp

First published 1956.

Harry The Dirty Dog is favoured for use in the preschool classroom to about year 3. Teachers can use the story to teach comparative adjectives, for example (dirty, dirtier, dirtiest). The story encourages a multi-sensory approach.

There are three more Harry books, and there may have been more had the writer and illustrator not divorced.

The Harry books have remained in print. There is now a companion DVD and various merchandise available.

COMPARE WITH

Harry The Dirty Dog is an example of a ‘carnivalesque‘ picture book. When a work of literature is ‘carnivalesque’, this refers to a literary mode that subverts and liberates the assumptions of the dominant style or atmosphere through humour and chaos. A naughty childlike character misbehaves, goes out into the world and returns home to safety and order.

Another classic which follows this storyline — this time with a human protagonist and an imaginary adventure — is Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak.