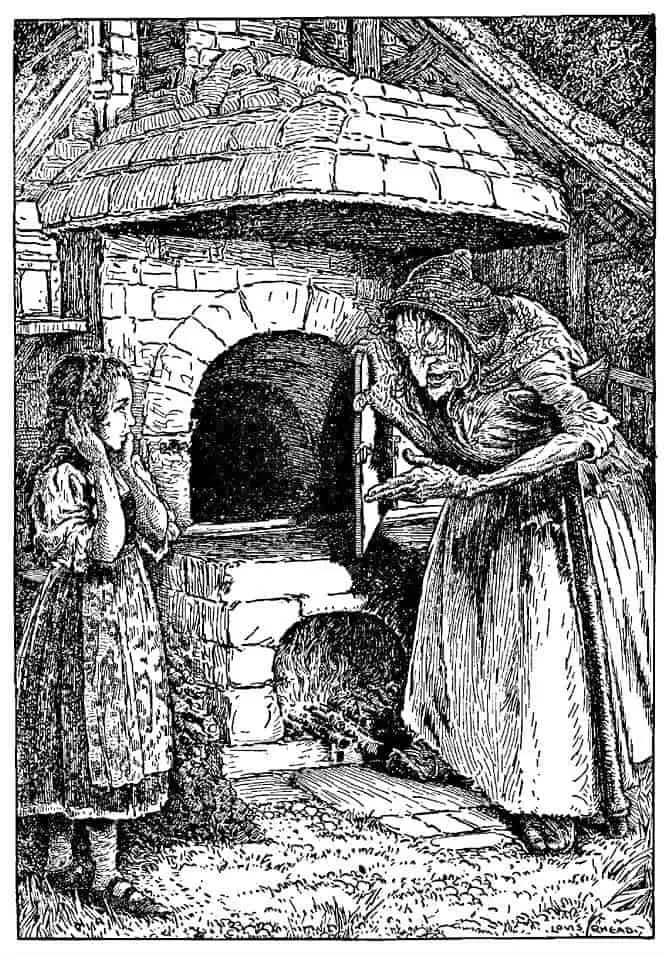

Hansel and Gretel is one of the best-known fairytales. Almost everybody knows the basic story but, more than that, this tale is the ur-story for many seemingly unrelated modern ones. For example, whenever a character meets a character in a ‘forest’ (whether the forest is symbolic or not), the audience is put in mind of wicked cannibalistic witches.

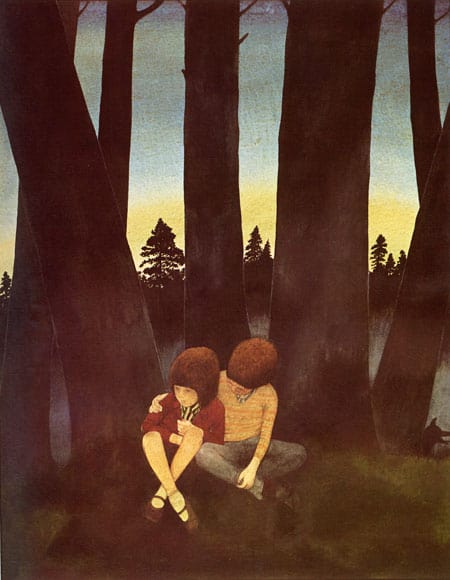

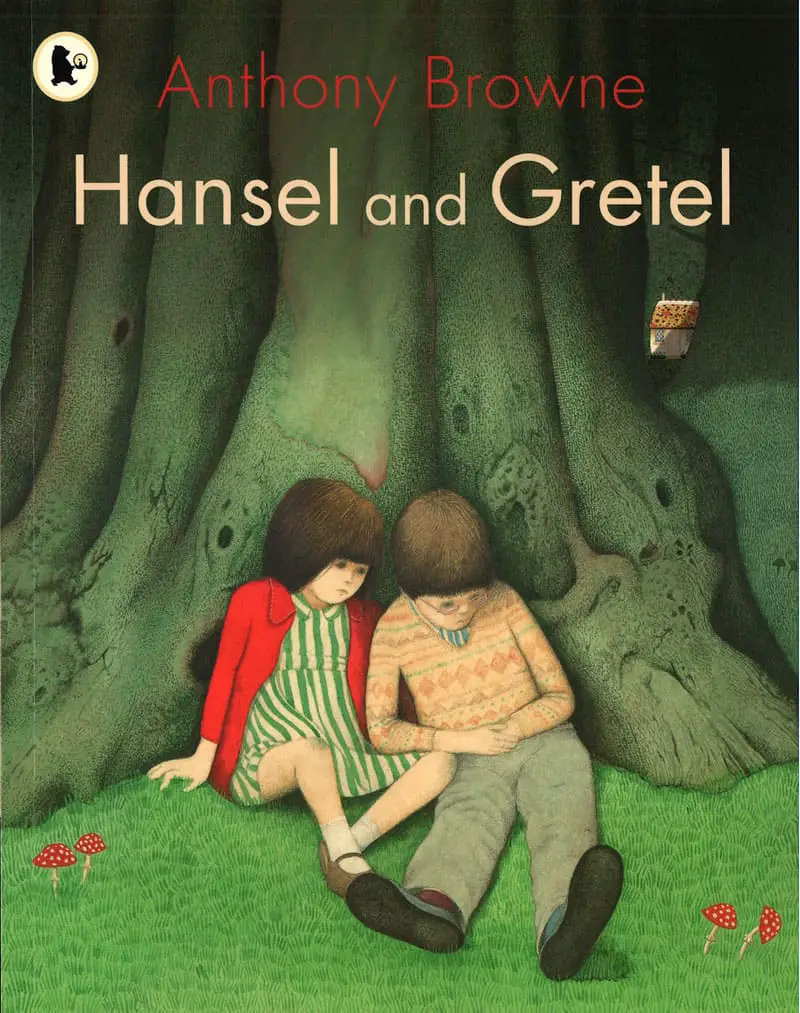

Let’s face it: The tale itself is basically terrifying. Anthony Browne, with his postmodern approach to its retelling, does not shy away from the terror. Later, Neil Gaiman and Lorenzo Matotti created an even darker version.

If you’d like to hear “Hansel and Gretel” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Hansel” was published in two parts in January 2021.

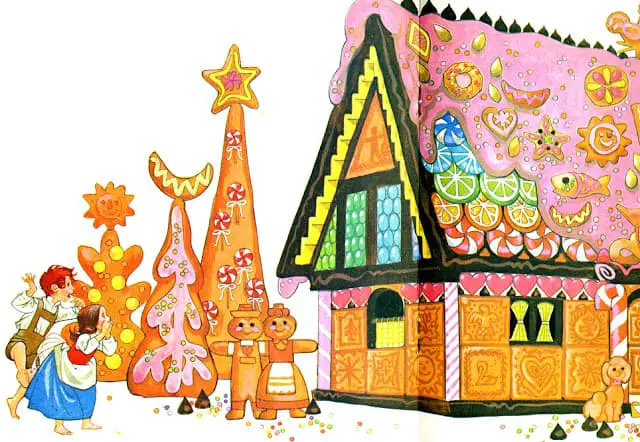

‘Sweetened’ Versions of Hansel and Gretel

My kid does not like the Anthony Browne version of Hansel and Gretel. For them it is too scary. They don’t like the dark version illustrated by Lorenzo Mattoti, either, preferring the cheap Ladybird edition with its brighter colours. This might explain why many illustrators of Hansel and Gretel — and there have been many — are not interested in what the story is really about, because the original is just too horrible.

The sweetening of this tale started with the Grimm brothers, who needed to make money to support their collection hobby, so they rewrote some of the horrible tales into versions they considered appropriate for middle class children.

Japanese Story With Similar Plot Points

There is a Japanese folktale called ‘The Three Brothers and the Oni‘ that is similar to the German tale known as Hansel and Gretel. In the Japanese tale, a mother who couldn’t afford to feed her three children takes them deep into the woods and asks them to wait while she goes to hunt for food. The three boys soon realised that she was not coming back. The two youngest boys began to cry, but the older boy (who was only seven years old) suggested they climb up a nearby tree to see if they could find anywhere that they could sleep for the night. In the distance they noticed a little house and so they set off and wandered through the woods towards it. By the time they arrived at the house it was already dark.

Curious Ordinary

The Grimm Brothers Made It Worse, As Usual

By that I mean, they made it horribly patriarchal. And we’ve been using their version ever since, sweetening it up a little, but the basic patriarchal message is the same:

The Grimm brothers rewrote and refined their version of the tale before it was published in 1857. It bears little resemblance to the original oral tale told to Wilhelm in 1810. While the mother figure is clearly demonized in this story, the father’s involvement in abandoning his children is carefully downplayed.

from Carolyn Daniel’s book Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

The main differences in the oral version:

- The opponent was originally a mother, not a stepmother. The Grimm brothers obviously thought that having your blood mother turn on you was too scary. They did retain the shortened form of ‘mother’ in some passages though.

- The mother/stepmother grows harsher.

- The father grows more introspective and milder.

- Wilhelm made the tale more dramatic, more literary, and more sentimental. For example, the children’s escape from the sinister woods across a large body of water, one at a time, on the back of a duck. In the original they simply run home.

Anthony Browne’s Hansel and Gretel

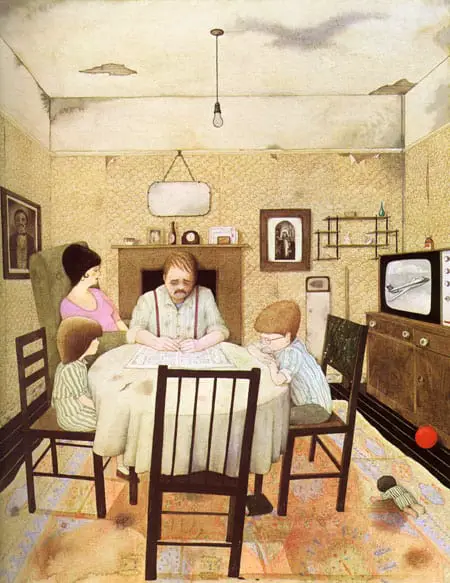

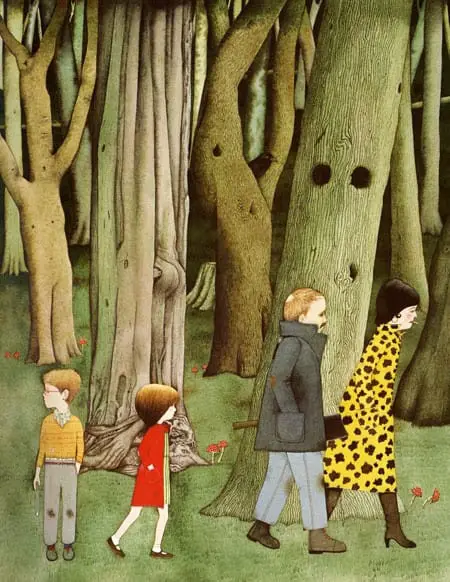

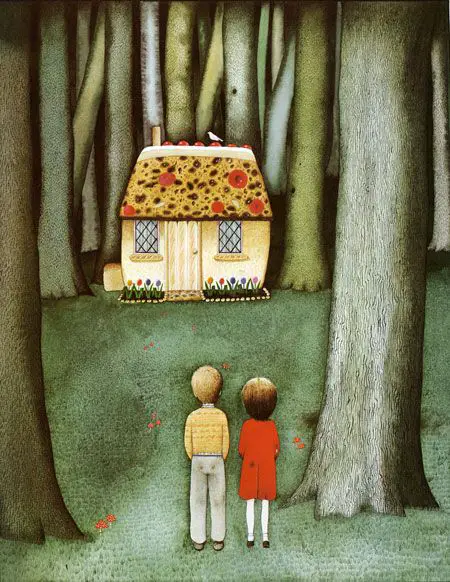

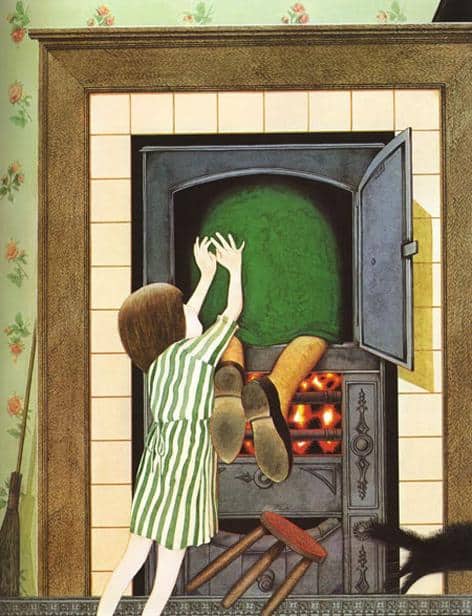

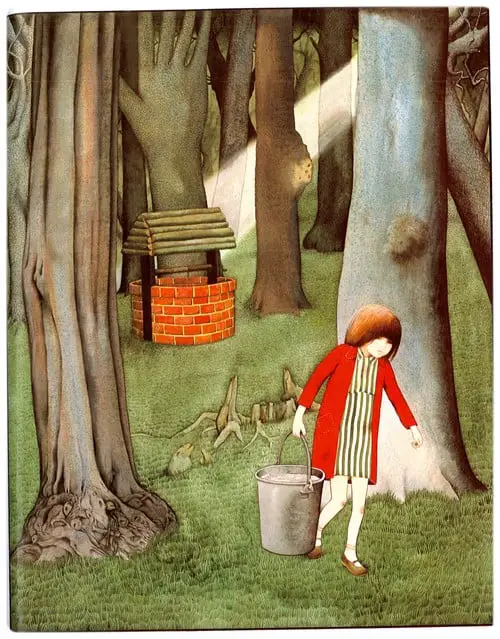

Anthony Browne is one writer/illustrator who does understand what this tale is really about, though he does go with something more like the Grimm modification rather than the original, oral tale.

This is no sweetened version. The fact that this is a modern setting, with a TV and a step-mother who smokes cigarettes, and that they live in a brownstone detached house mean that the child reader can no longer pretend abandonment and famine happen only in ‘fairytale land’.

Here’s the thing Browne underscores the most:

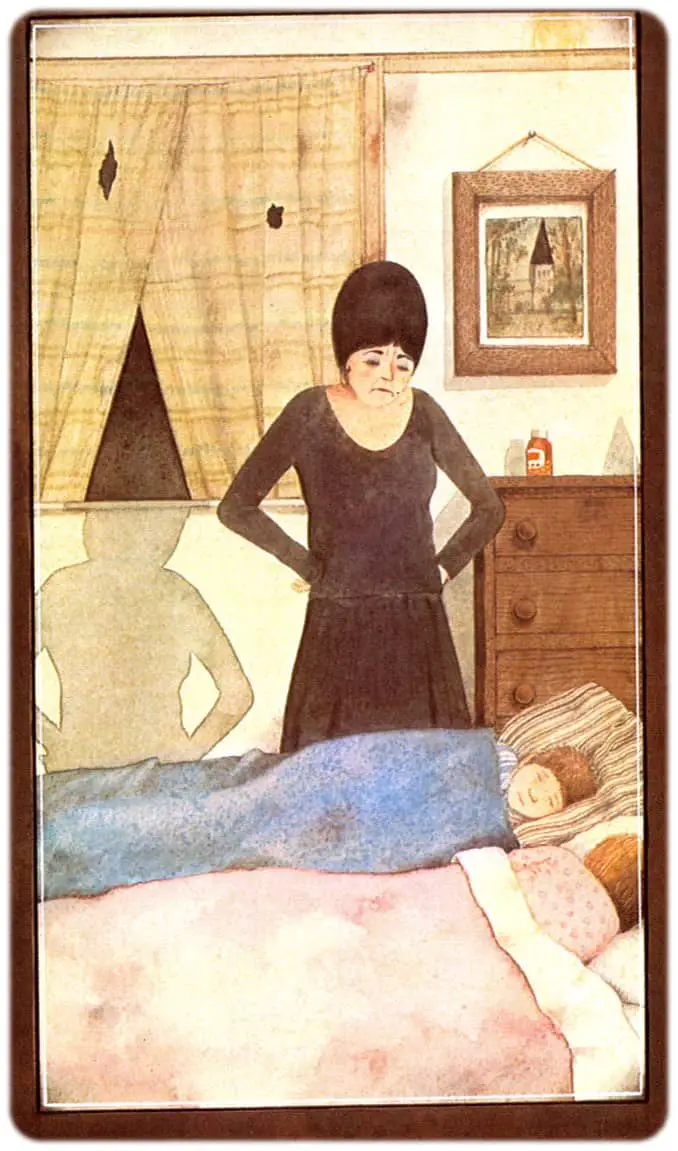

The mother and the witch are the same person.

In Hansel and Gretel, the mother figure is split … and clearly has cannibalistic desires.

from Carolyn Daniel’s book Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Daniels further explains the double/duplicitous/split nature of the (step)mother/witch with the help of some 20th C psychoanalysis:

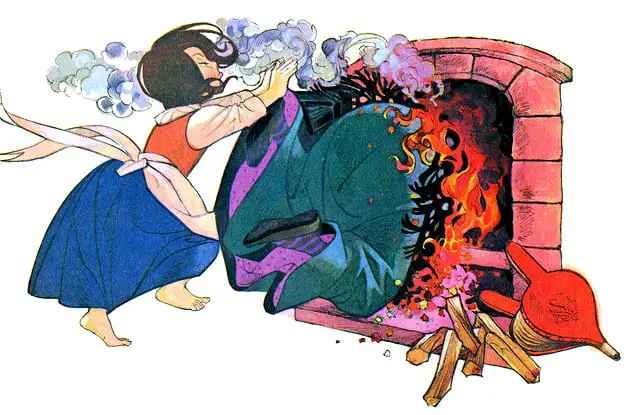

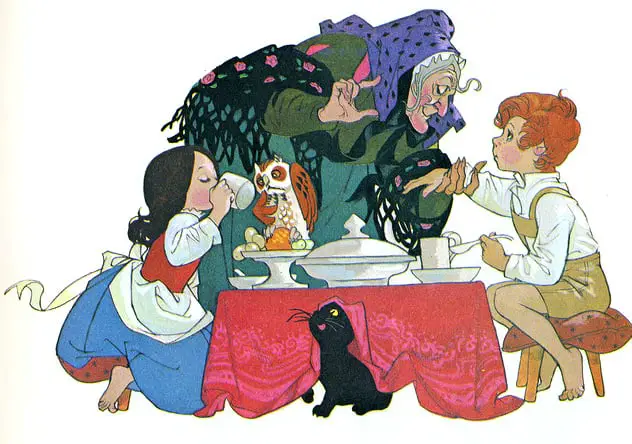

The witch locks Hansel up in a cage and wakes Gretel up by yelling: “Get up you lazybones! I want you to fetch some water and cook your brother something nice. He’s sitting outside in a pen, and we’ve got to fatten him up. Then, when he’s fat enough, I’m going to eat him.”

This is a portrait of a powerful cannibalistic woman, the bad mother, who is directly juxtaposed with the good mother figure. Two facets of the mother figure are represented in this fairy tale: the evil, threatening, cannibalistic one embodied by the witch/stepmother and the comforting, feeding persona initially presented by the old woman to lure the children. The link between the stepmother and the witch is made explicitly — they both wake the children with the phrase “Get up, you lazybones” and they are both dead by the end of the story: the stepmother is the facet of the bad mother/breast who denies the children nourishment and abandons them; the witch is the mother/breast who threatens to retaliate. The duplicitousness of the bad mother is also emphasized: in her manifestation as the stepmother she pretends to be as pleased when the children find their way home; as the witch she pretends to be a kind, generous, good mother in order to lure the children into her house.

Oral Aggression?

Bruno Bettelheim [who was a total asshole, by the way — I can’t write about him without slipping that in there] considers “Hansel and Gretel” to be a tale about a child’s inappropriate oral aggression, that “gives body to the anxieties and learning tasks of the young child who must overcome and sublimate his primitive incorporative and thus destructive desires.” But it is noteworthy that in this tale the children are orally nonaggressive. They do break off pieces of the house and “nibble” them but then they are about to “perish of hunger and exhaustion” (Grimms.) It is the witch who is aggressive and cannibalistic, but Bettelheim does not discuss this.

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

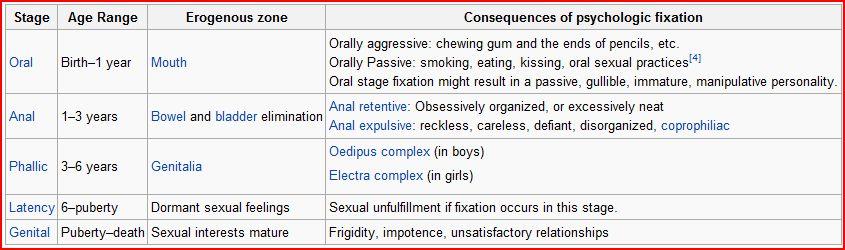

Hansel and Gretel and Child Development

I’m no Freudian, but here’s some quoted psychoanalysis if you like.

It is interesting to consider the ending of the tale in terms of psychoanalytic notions of child development. The children’s task is to escape the clutches of the devouring mother and to proceed from the oral phase to the oedipal stage and a meaningful relationship with their father. They live in her house for a month while she feeds Hansel on “the very best food” and waits for him to get fatter. Hansel, then, partakes of the good breast while Gretel, who “got nothing but grab shells” to eat, is denied it. They are clearly in the oral, pre-oedipal phase. By threatening to eat Hansel, the witch/bad mother clearly intends to incorporate and psychically obliterate him. Gretel kills the witch/bad mother by pushing her into the oven so that she is “miserably burned to death”. The threat of incorporation she poses is thus neutralized.

Since the children have now successfully separated from the witch/mother, they are able to re-enter her house/domain “since they no longer had anything to fear.” There are children find “chests filled with pearls and jewels all over the place” and they fill pockets and apron with this treasure before leaving the house for good. Tracy Willard contends that while the good mother is not reclaimed literally or explicitly in this tale, she is symbolically reclaimed through the treasure the children find in her house. I suggest that this tale illustrates the process whereby children reconcile themselves to the duality of the mother; her presence and absence, her giving and withholding of food, and the gratification and frustration that result. The children in the tale not only kill off the bad mother but they also leave behind the oral phase. When they arrive at the house in the forest, all they are interested in is food (gratification from a maternal source), but when they leave the house/maternal domain they take treasure (economic wealth associated with the father) with them which enriches their lives, so that they can enter the paternal oedipal domain, and live with their father in “utmost joy”.

Willard […] sees the children’s home (or mother’s body) as a place that becomes hostile to them, expelling them into the forest and denying them food. They try to return but are rejected and thrust out to fend for themselves. The children find a house in the woods that appears to offer them what they desire (a return to the mother’s body) but it turns out to be a trap. Thus “the dangers of returning home are clearly outlined.” The children, Willard argues, must deal with the image of the split mother so that they can attain “a fully integrated image of the mother”. They do this by committing matricide, an act which Kristeva argues is the clearest path to autonomy. By killing the witch/bad mother, the children are free to return to their father, but they take with them the “best parts” of the split mother figure, symbolically represented by the jewels. […] The symbolism of food and the theme of eating (including cannibalism) in the story have profound psychic resonances with infantile anxieties relating to the mother which is arguably why the story continues to be popular.

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

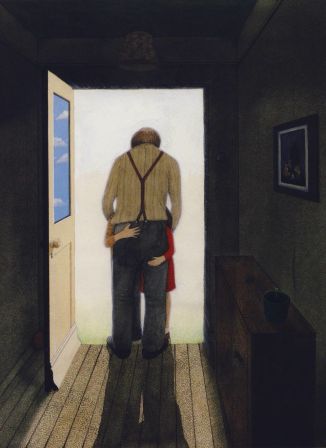

The Role Of The Father and ‘Mothers In Fridges’?

But what of the role of the father in this tale? The Grimm brothers’ version celebrates the oedipal complex and reinforces patriarchal hegemony. As Zipes argues, this story twice demonizes the omnipotent mother figure but it also, significantly, was rewritten by the Grimms in order to rationalize the abandonment of the children by their father and to bolster phallocentric discourses.Hansel and Gretel must, Zipes argues, “seek solace and security in a father, who becomes their ultimate authority figure” while the mother is conveniently killed off. This situation marries with Jessica Benjamin’s theorization of object relations whereby the child identifies with the mother and maternal power and turns to the father for help in order to overcome the perceived negative aspects of the mother. However, once his help/authority has been accepted the father figure remains in control, continues to dictate the child’s life, and can be “benevolent or sadistic”. Patriarchal hegemony and phallocentric logic are thus reinforced in the Grimms’ narrative and the outcome is rendered natural or rational.

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

SYMBOLISM IN “HANSEL AND GRETEL” BY ANTHONY BROWNE

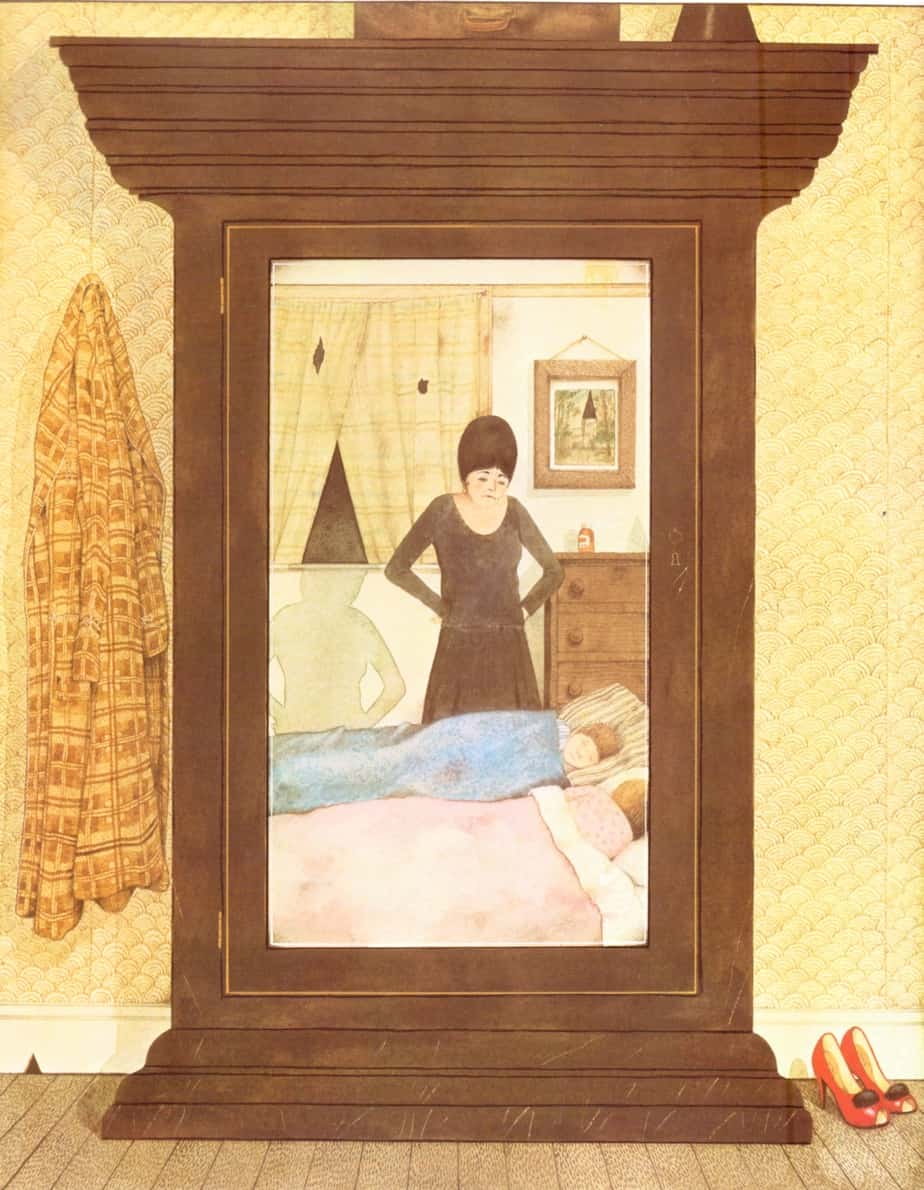

The Red Shoes

What do you associate red shoes with? Perhaps you associate them with the film version of The Wizard of Oz, in which the bad witch is squished under the house, her ruby slippers poking out?

“The Red Shoes” is a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, so not of the Grimm variety, but ‘fairytale’ enough for readers to get the possible meaning in the picture above, in which red shoes sit next to the mirrored wardrobe door.

A peasant girl named Karen is adopted by a rich old lady after her mother’s death and grows up vain and spoiled. Before her adoption, Karen had a rough pair of red shoes; now she has her adoptive mother buy her a pair of red shoes fit for a princess. After Karen repeatedly wears them to church, they begin to move by themselves, but she is able to get them off. One day, when her adoptive mother becomes ill, Karen goes to a party in her red shoes. A mysterious soldier appears and makes strange remarks about what beautiful dancing shoes Karen has. Soon after, Karen’s shoes begin to move by themselves again, but this time they can’t come off. The shoes continue to dance, night and day, rain or shine, through fields and meadows, and through brambles and briers that tear at Karen’s limbs. She can’t even attend her adoptive mother’s funeral. An angel appears to her, bearing a sword, and condemns her to dance even after she dies, as a warning to vain children everywhere. Karen begs for mercy but the red shoes take her away before she hears the angel’s reply. Karen finds an executioner and asks him to chop off her feet. He does so but the shoes continue to dance, even with Karen’s amputated feet inside them. The executioner gives her a pair of wooden feet and crutches, and teaches her the criminals’ psalm. Thinking that she has suffered enough for the red shoes, Karen decides to go to church so people can see her. Yet her amputated feet, still in the red shoes, dance before her, barring the way. The following Sunday she tries again, thinking she is at least as good as the others in church, but again the dancing red shoes bar the way. Karen gets a job as a maid in the parsonage, but when Sunday comes she dares not go to church. Instead she sits alone at home and prays to God for help. The angel reappears, now bearing a spray of roses, and gives Karen the mercy she asked for: her heart becomes so filled with sunshine, peace, and joy that it bursts. Her soul flies on sunshine to Heaven, where no one mentions the red shoes.

Wikipedia summary

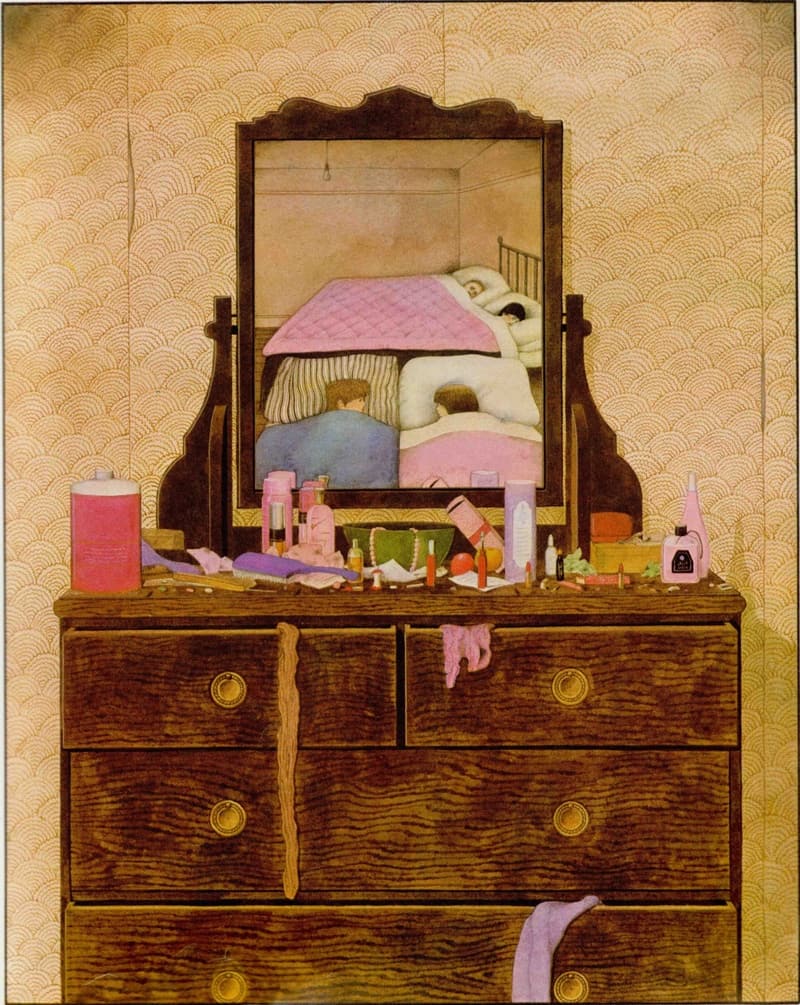

The pink fripperies spilling out of the dresser drawers suggest several things about this step-mother:

- She is not a good housewife (when the implication is that a good housewife is also a good mother, and that being a good housekeeper is the job of the woman.

- That women who are over-the-top feminine — look at all the feminine accoutrements, signified by the colour pink — are over-the-top vain. The mirror adds to the impression of vanity, and we will subconsciously conjure up Snow White and the magic mirror in that tale.

Note that the step-mother has not one but two mirrors in her bedroom, which is considered excessively vain, but apart from that, there’s the whole ‘witch/mother’ mirroring going on.

CANNIBALISM

10 Historic Famines That Caused Cannibalism

Repulsive as it sounds in times of plenty, cannibalism in times of famine isn’t all that unusual.

George Devereaux, citing “Multatuli (1868),” pseudonym of novelist Edward Douwes Dekker, reports that during medieval famines and “even during the great postrevolutionary famine in Russia” the “actual eating of one’s children or the marketing of their flesh” occurred. He concludes that “the eating of children in times of food shortage is far from rare.”

Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Maria Tatar argues that although mothers did eat their children, it was generally only due to mental derangement caused by her own starvation. In medical/legal documents it was always a baby who was eaten rather than an older child.

In modern literature, there is a horrific scene in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in which the main characters happen across a baby being roasted on a spit. It seems McCarthy, also, understands that babies are more likely to be eaten than older children in times of famine.

Paternal cannibalism is of a different nature and can be seen in The Juniper Tree (sometimes called The Almond Tree). In cases where the father eats his child in a fairytale, Tatar sees it as an expression of ‘biological ownership through incorporation’. The child can (in a strange sort of way) live on via being made into the father’s own body. The father in the Juniper Tree is not cast as good or evil in the same way fairy tale mothers are.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH HANSEL AND GRETEL

Other fairytales that start in a time of famine:

- Tom Thumb

- The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn

- God’s Food

- The Sweet Porridge — better known in English speaking countries as The (Magic) Porridge Pot

- The Children of Famine — exemplifies the plight of families unable to feed their kids. The mother becomes unhinged and desperate when she is unable to feed her own children.

- Little Red Riding Hood also has cannibalistic elements which are sometimes sanitised. This tale is pretty much the only European tale in which a good — a good girl no less — is involved in cannibalism.

Anthony Browne wasn’t the first to take two separate women from “Hansel and Gretel” and merge them together as one. In her short story “Angel Maker” (1996), Sara Maitland Maitland rewrites ”Hansel and Gretel” from the perspective of the witch. Over her adult lifetime, Gretel regularly visits the witch for abortions. At the age of 38 she now wishes to become pregnant, and this time visits the witch for a different reason. The witch and Gretel are the same person.

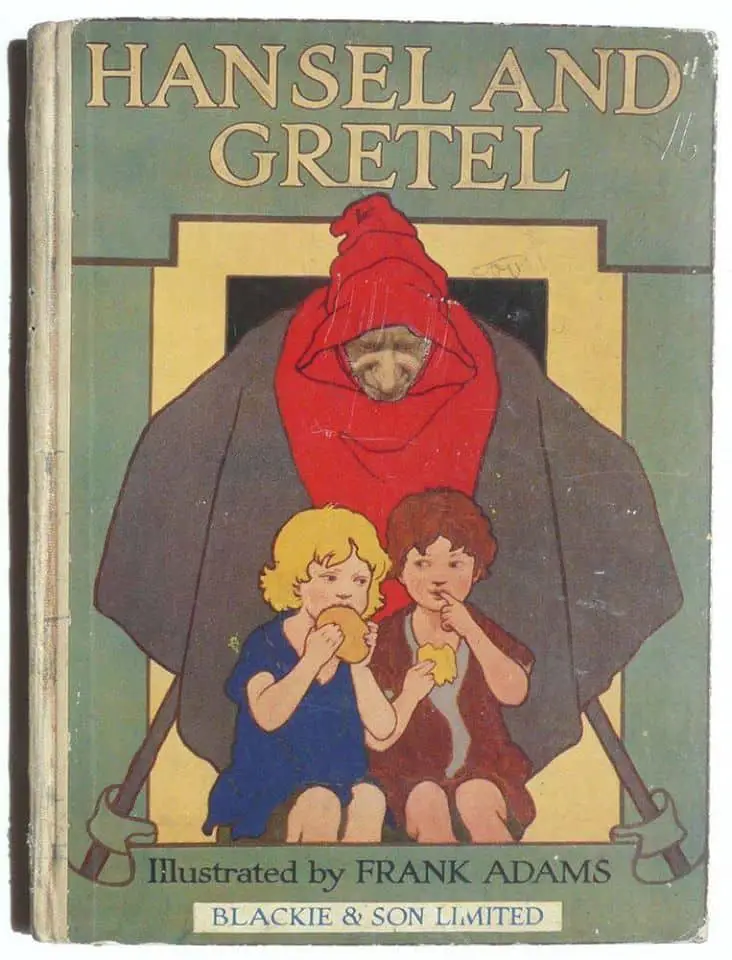

Anthony Browne’s compositions remind me of the version below, illustrated by Frank Adams.

Many fairy tales have their roots in a much darker past, but these origins are watered down to make the tales more wholesome or moral. But did the story of Hansel and Gretel really stem from a case of entrepreneurial intrigue and murder in 17th century Germany? And did the Grimm Brothers know more than they were letting on it their version of the story? Why do the illustrations in their book look so similar to modern day locations? In this episode of The Folklore Podcast, creator and host Mark Norman examines a case to which their is certainly more than it seems at first glance.

Gaiman and Matotti’s Hansel and Gretel

One of the best ways to retell a familiar story is to add plenty of minor detail. The trick is to make this detail seem both unexpected and surprising. There are things I really like about Gaiman’s retelling of Hansel and Gretel:

1. In earlier retellings, it is Hansel who has all the bright ideas. Hansel realises what the parents/step-mother has done to them — abandoned them in the woods. By comparison, Gretel seems naiive and even stupid. In this retelling, Gaiman offsets this interpretation by making Hansel — but not Gretel — privy to an overheard midnight conversation between the mother and the father.

2. So often in fairytale retellings, it is a step-mother rather than a birth mother who is evil. It is generally thought that a story with an evil mother is too terrible for a young reader to contemplate. If there are unwritten rules in children’s literature (and indeed, there must be few these days, if we include young adult literature), it is that mothers must love their children unconditionally, even if they themselves are too screwed up to care for them properly. If you went looking for terrible mothers in children’s literature you’d be hard pressed to count the evil ones on one hand. But Neil Gaiman does not shy away from the reality that some women do indeed lack mothering instincts, just as many men lack fathering instincts.

3. Not only that, Neil Gaiman portrays gut-wrenching emotion in the father. Counterintuitively, this is what makes this story feminist — a story in which women are not put on a pedestal as mothers, where women have only one representation: self-sacrificing and emotional. In stories, men are often allowed to be just men, even when they have children. They are not judged so much on how effective they are as fathers. In this story, however, the father is the parent with the nurturing instinct, and is at the mercy of his wife’s terrible decisions rather than the other way around. We won’t have gender equality until we have as many bad mothers as there are bad fathers, I guess.

Food In Fairytales

Carolyn Daniel writes in Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature:

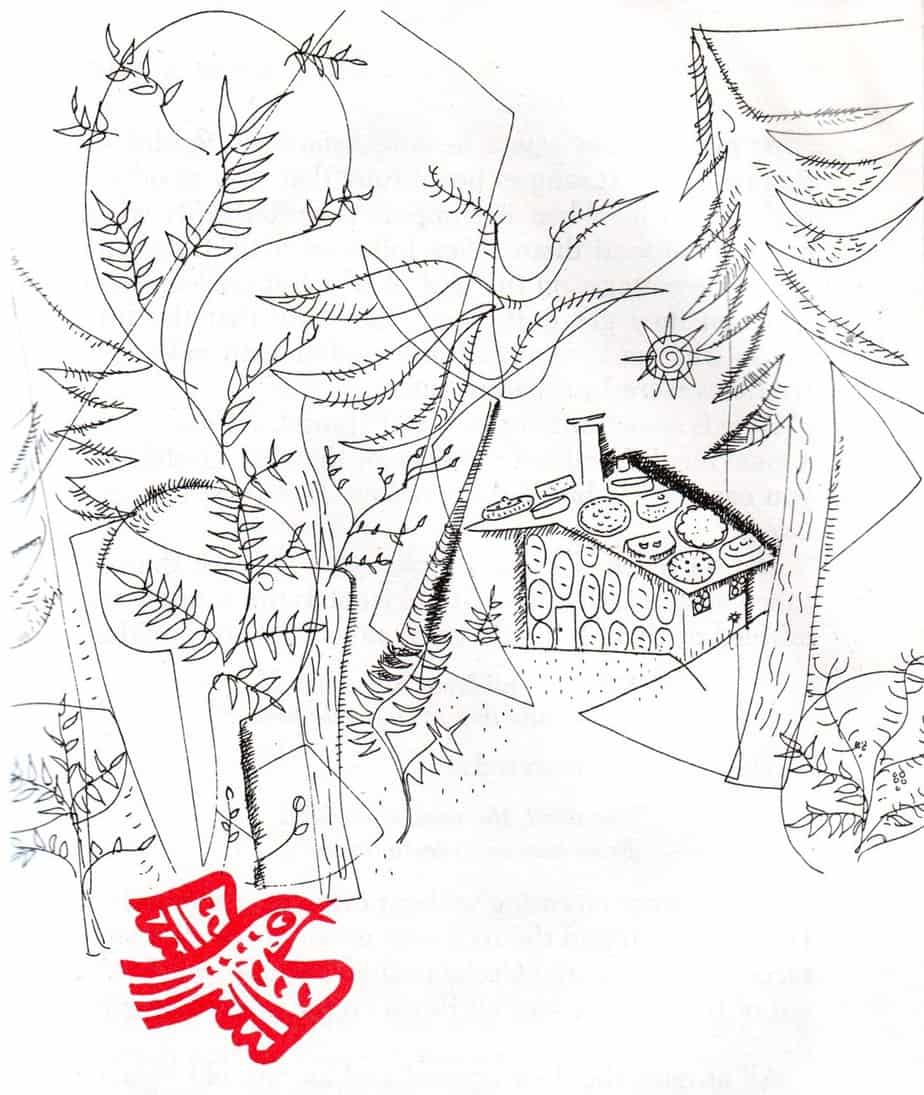

The woodcutter’s family is poor and they “did not have much food around the house, and when a great famine devastated the entire country, [the woodcutter] could no longer provide enough for his family’s daily meals”. At the suggestion of their stepmother, Hansel and Gretel are abandoned in the woods. The hungry children come across a house made, in the Grimm version, of “bread” with “cake for a roof and pure sugar for windows”. Cane sugar was a very costly commodity and had been imported from India or Arabia since the eleventh century. It was used for making marzipan and other sweetmeats. Sugar would only have been available to rich nobles and not to woodcutters and their families. The house made of sweet food represents something exotic, very rich, and beyond the reach of the peasantry. When your diet is poor and monotonous, a story featuring plentiful, appetizing food is bound to have appeal, but I believe this fantasy goes beyond the desire to alleviate hunger: it also represents economic desire. The exoticism and richness of the sugary food in the fantasy represent not only the riches of the nobility but also their ability to avoid the hunger and drudgery of the peasants’ daily life. The Grimm version ends with the children filling apron and pockets with the pearls and jewels they have found in the witch’s house and taking them home to their father. “[In] the meantime” their stepmother has died and so “Now all their troubles were over, and they lived together in utmost joy”. Their future is secured by the wealth with which, like the nobility, they can now live in relative ease and luxury. Unlike the magic porridge pot that merely alleviated hunger, the jewels provide the woodcutter’s family with riches and instant freedom from their menial existence.

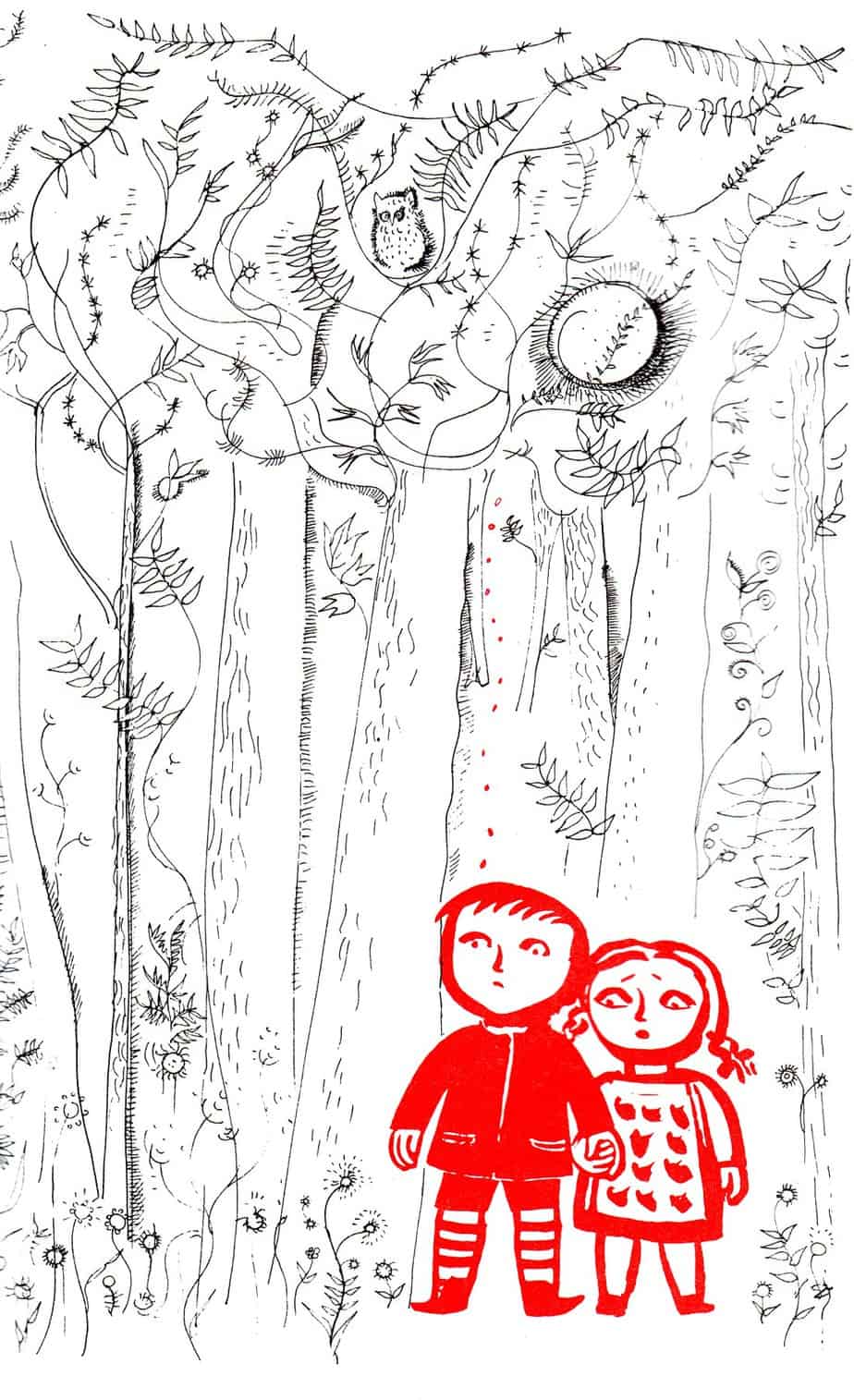

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS IN HANSEL AND GRETEL BY GAIMAN AND MATOTTI

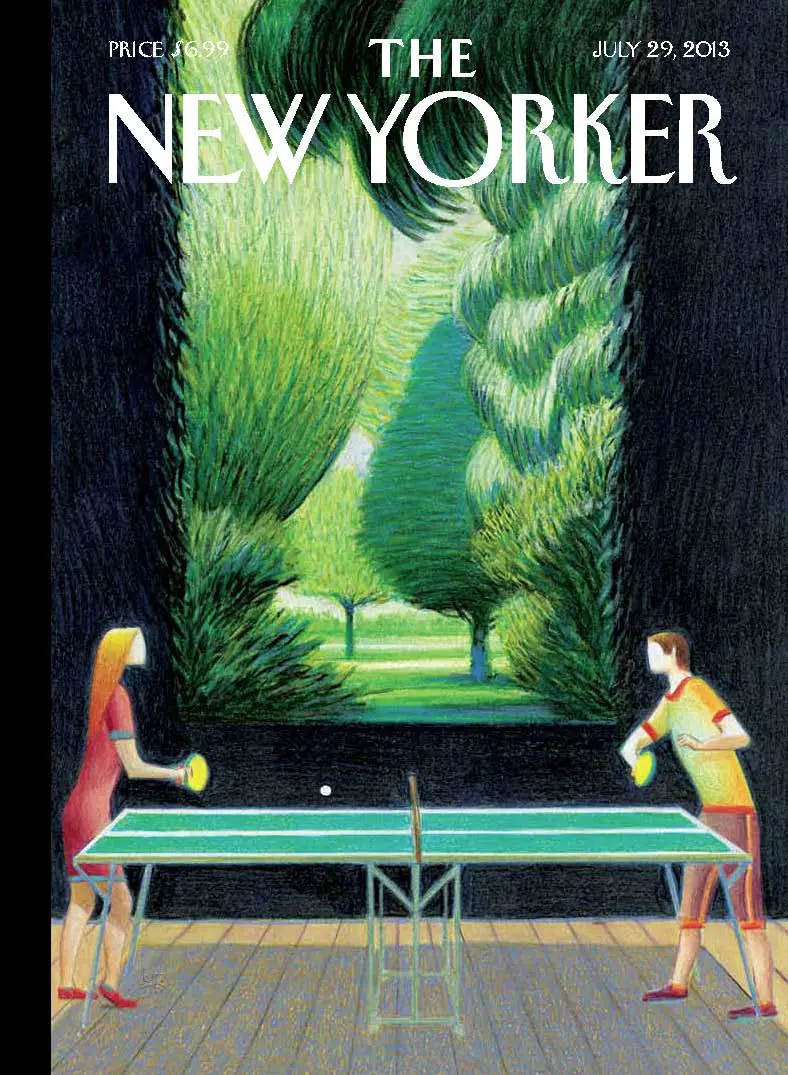

I knew before picking this book up that the illustrations were in black and white, but what I didn’t expect was that many of the illustrations would be — literally — black and white, with basically no greys, just #FFFFFF and #000000. There is a little green on the cover, but not within the pages. Mattotti does not always paint in black and white. In fact, a lot of his work has quite interesting use of colour. Note all the different colours in the shadow of the ping-pong table — the shadow is as alive as the foliage. The woman’s blonde hair turns to red as it blends into her dress. The green of the table reflects onto the yellow t-shirt. Colour or no colour, there’s something ‘creepy’ about Mattotti’s people. Here they have no faces, and their profiles are uncompromisingly angular, as are the elbows. Body proportion is slightly morphed, with an unusually long-waisted man.

For Hansel and Gretel, the choice was made to leave out any colour. It is extraordinarily difficult to paint detailed scenes using only the whitest white and the blackest black, unless you’re working with black outlines on white paper, of course, but these illustrations are filled in with blocks of black and we still know what the scenes are. This is quite a magic trick.

Why the absence of colour?

Of David Macaulay’s book Unbuilding, Perry Nodelman writes in Words About Pictures:

In black and white, [the drawings] achieve the tongue-in-cheek pseudoconviction of fairy tales, that characteristically matter-of-fact reporting of utterly nonfactual events.

Is that partly what’s going on here, too, when the publishers decided to employ an artist who would work in black and white? I suspect the ‘documentary realism’ is part of it; added to that is the universal fear of darkness, most dramatically rendered in black. Nodelman says that although some artists achieve a sense of reality by imitating and thus evoking our conventional expectations of conventionally realistic depictions/photographs and artists’ sketches

in other circumstances, black-and-white drawing is not necessarily a good medium for the representational depiction of the way the world looks. It shows us less of the visual world than our eyes do—shades, but no hues—and forces us to fill in what is not actually shown. Perhaps that explains why black-and-white documentary seems so truthful and serious—it demands our mental activity, so that we cannot just sit back and soak it in. But since black-and-white pictures are, in fact, less complete than those in colour, they actually reveal less of surfaces, of physical objects and facial characteristics.

Furthermore, colour, placed in between the lines that represent objects, fills in shapes and gives the objects solidity; so without colour, the lines become more obvious, and without the solidifying qualities of weightiness and bulk they can more forcefully depict motion. Generally speaking, and unlike the work of Van Allsburg and Macaulay, most of the black and white drawing in picture books is cartooning and caricature, and most of it emphasizes action over appearance-not how objects look but what they do.

This focus also explains why black-and-white illustrations seem so much more appropriate in longer books than in picture books. Picture books emphasise showing as much as telling, and their pictures often fill in the details of emotion and of setting that their words leave out and that color seems most suited to convey. But in longer books, words can convey at least some of those details, and pictures in color seem superfluous when they merely duplicate information the text itself communicates. On the other hand, good black-and-white pictures that emphasize line over shape can add energy to long books in which details of emotion and of setting might otherwise retard the action.

If you enjoy Lorenzo Mattotti’s illustrations for Hansel and Gretel, you may also enjoy illustrations by Savva Brodsky.

As examples, Nodelman offers the work of Garth Williams (Charlotte’s Web), Tenniel (Alice In Wonderland) and Shepherd (Winnie the Pooh). All three examples emphasize line over shape. Even the blackest of spaces retains evidence of crosshatching in small bits of un-inked white, but not in the work of Mattotti. Mattotti’s pictures are without cross-hatching or other traditional methods of rendering form.

STORY SPECS

At 54 pages, this is longer than a picturebook for preschoolers. This is more of an ‘illustrated short story’ for older children and adults.

Published October 28th 2014

This book was released in a ‘Standard Edition’ and in an ‘Oversized Deluxe Edition (A Toon Graphic)‘. In the deluxe edition the pages are larger (9.125″ x 12.625″), there is a die cut in the front cover, and some of the after matter is missing. Due to the larger size, there is more white space around the text. This raises interesting questions about what a ‘deluxe’ version of a picture book should include over the standard version. There is also a collector’s edition, which is signed and includes a screen-printed box and artist print.

Juliet Blake has the rights to turn this version of Hansel and Gretel into a film. (See Juliet Blake at IMDb, in which we learn the film stars Josh Hutcherson and Elle Fanning.)

COMPARE WITH

For A Similar Art Style

Wanda Gag (1893-1946) illustrated the children’s book Millions of Cats (1928), and pioneered the double-page book spread, using both pages for one illustration that furthered the story. In Millions Of Cats there is use of bright colour, but a lot of her work is high-contrast black-and-white. This is achieved via lithography, whereas Mattotti uses a paint brush.

The billowing tree and off-kilter palings of the foreground fence remind me of similar techniques used by Mattotti in Hansel and Gretel. This way of drawing makes for a creepy vibe.

Perry Nodelman in Words About Pictures finds the curved forms comforting as much as creepy, and speaks of the comfort of a predictable, oft-told tale:

[Not all] artists in black and white focus on the energies of line. Some, like Wanda Gag, use black-and-white’s potential for heavy contrast to create more restfully decorative effects. Even though there’s must use of line to create shadow in Gag’s Millions of Cats, the heavy contrasts between light areas and dark ones orient the pictures toward pattern rather than toward action. In techniques like block printing, in which the ink is not laid down on the paper by the line of a pen, the blocks of black and white tend to operate more like colors, creating solid shapes rather than energetic lines. Furthermore, such a technique associates these pictures with the static conventions of folk art, which tends to be more oriented to pattern than to action. Not surprisingly, Gag’s story also focuses more on pattern than on movement, on repetition rather than on forward movement. While a lot happens in Millions of Cats, the story tends to offer more pleasure to those who have heard it before than to those who are hearing it for the first time. It is comfortingly predictable rather than threatening or even very exciting.

But if Millions of Cats is comfortingly secure, it is not just because it emphasizes shape over line, pattern over energy; it is also because the shapes happen to be primarily rounded and curved ones—the sort of shapes we associate with softness and yielding. Such associations have an obvious effect on our attitudes to pictures.

Nodelman then mentions the art of Tim Burton, which has been replicated by subsequent animators in films such as Paranorman.

I would also compare the art of Manttotti to that of Armin Greeder, who has illustrated The Great Bear and The Island in a style which you’re more likely to find in an unsettling art exhibition than a book for children:

When a fairytale is republished for the modern reader, the new story may function as several different things: Is it a comfort read, ideally suited to pre-bedtime reading? Or is the very familiarity of the tale a great bedrock upon which to branch out with unsettling art, creating something brand new?

For Another Re-visioned Classic Fairytale For Older Readers

Shameless plug: Compare with our own retelling of a classic fairytale, Lotta: Red Riding Hood. Of course, there are many other modern retellings of fairytales, and like ours, many of them are written for young adults and above, as were the original tales. (I mean pre-Grimm. The Grimm brothers needed to raise money, so published old tales as children’s stories, because children’s stories are what sold.)

WRITE YOUR OWN

Is there a classic tale from your childhood which feel to you like some parts are missing? Perhaps one character doesn’t get a fair deal. I often feel that way about female characters in fairytales when retold by Perrault and Grimm; in the Victorian era, women were ideally stupid and innocent. Around this time step-mothers started to become most vilified. Beautiful people are portrayed to be good; ugly people are bad.

What might an ameliorated, more socially just version of your tale look like? Like Gaiman’s Hansel and Gretel, it may be quite similar to the classic version, but with a few details altered.

SEE ALSO

Maria Popova of Brainpickings links to some videos of Gaiman talking about fairy tales.

American author Robert Coover wrote a short story called ‘The Gingerbread House’ and it can be found in his collection Pricksongs and Descants. It’s Angela Carter style, if you’re familiar with those.

GRETEL & HANSEL

Oz Perkins’ Gretel & Hansel attempts to reimagine the folktale ‘Hansel & Gretel’ as an empowering coming of age story for its titular female heroine, complete with an ecoGothic stylistic flare. However, the film is just that: style over substance. While it seeks to, on the one hand, prioritise the feminist development of Gretel and, on the other, foreground its moody natural environment, it ultimately falls short on both counts. The overall result is a rather overwritten and poorly executed ‘girl power’ film which fails to unnerve or excite us with its ecoGothic aesthetic

Folktale Failure: Gretel & Hansel by Shelby Carr

Header illustration by Sheilah Beckett.