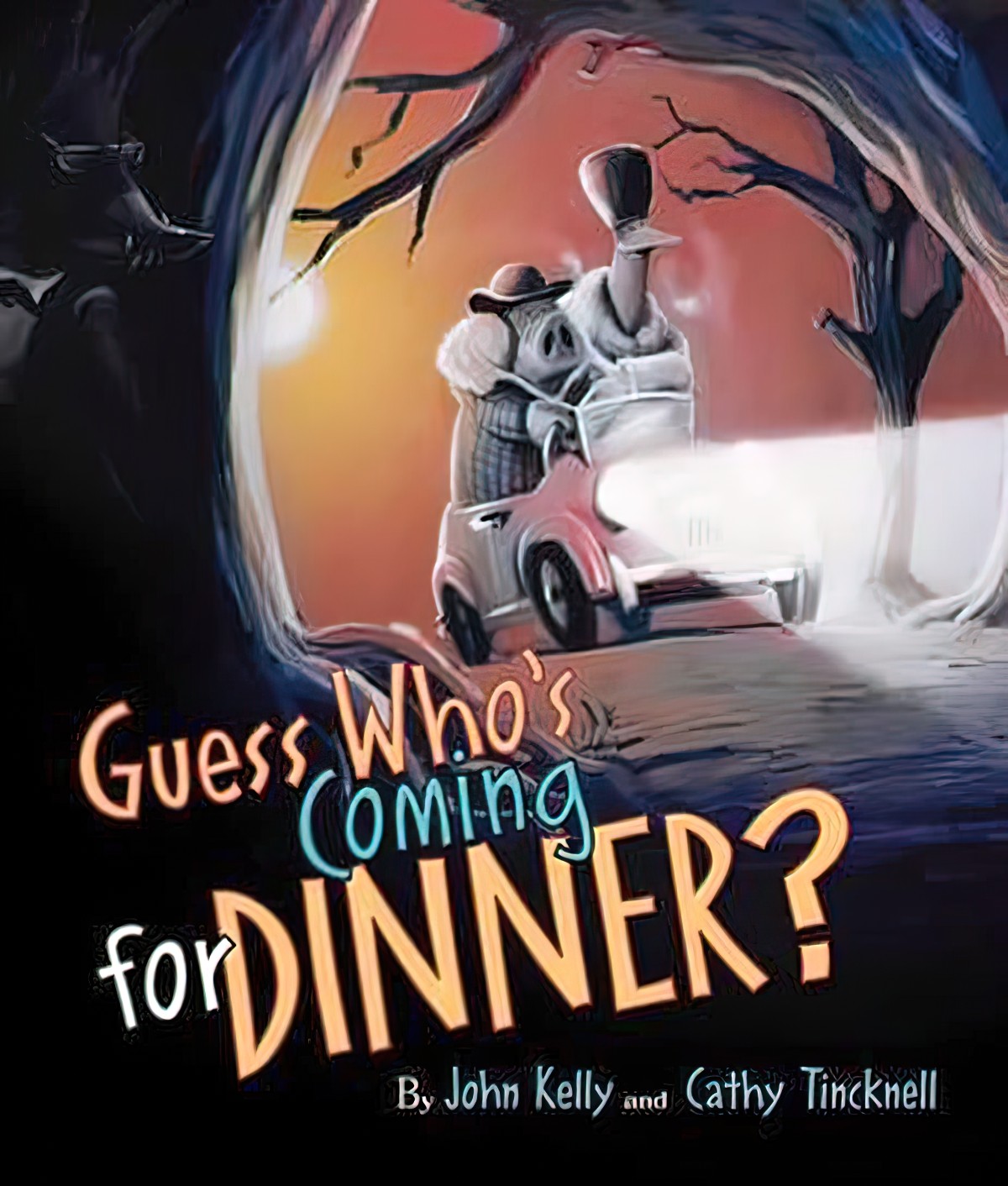

Guess Who’s Coming For Dinner is one of my all-time favourite picture books and funnily enough, it has been created by a husband and wife team. Some of the very best picture books are obviously created with a lot of collaboration between writer and illustrator, and it amazes me that so many (also good) picture books are created without writer and illustrator ever meeting.

PLOT OF GUESS WHO’S COMING FOR DINNER

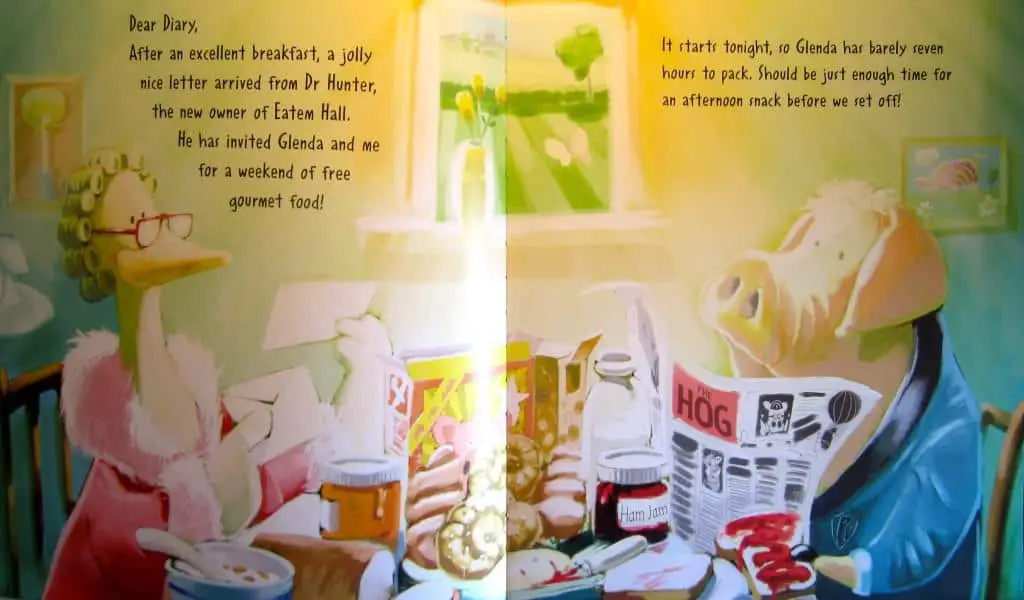

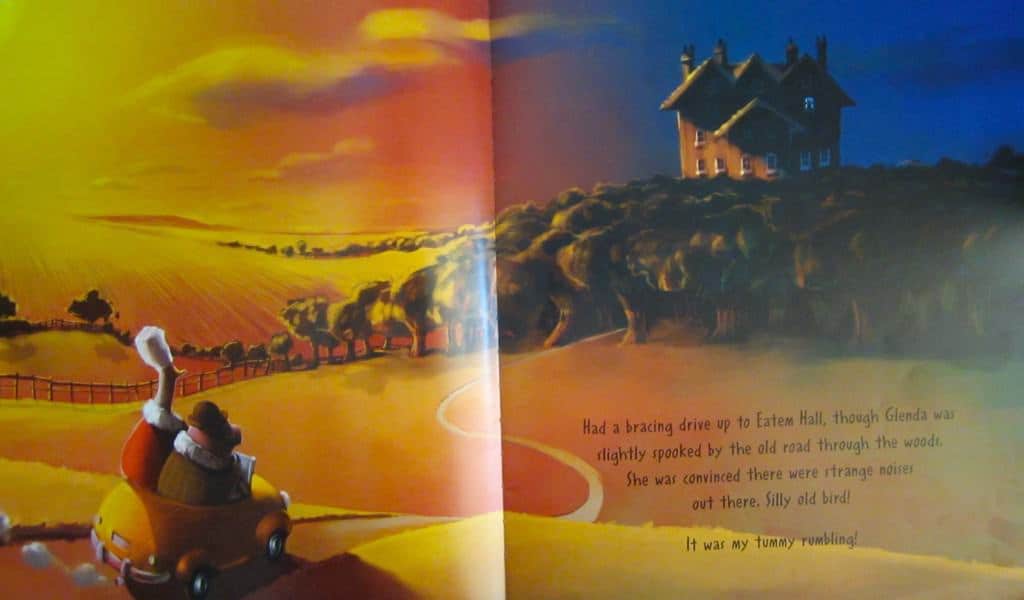

Horace and Glenda Pork-Fowler hav one an “all-you-can-eat” weekend at Eatum Hall – a dream come true for the pair for whom no plate is too big. However, their greed and desire to make the most of their luxurious surroundings distract them from the true purpose of why they are there!

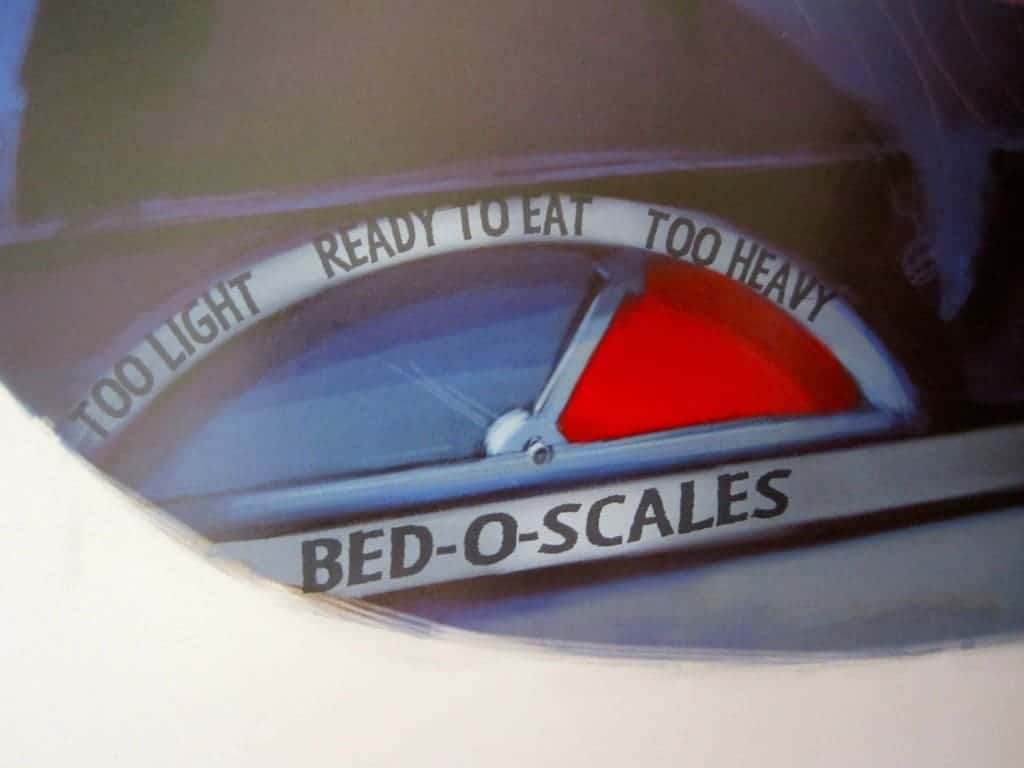

Gradually we are fed details about the wolf’s intentions: He intends to fatten up his dinner guests then trap them in a giant pie machine. After he has cooked bacon and goose pie, he will invite his wolf cronies for a feast.

Needless to say, the wolf’s plan backfires. The Pork-Fowlers escape unharmed.

WONDERFULNESS IN GUESS WHO’S COMING FOR DINNER

Although marketed at ages 5+*, I have to admit not fully understanding what had happened after the first time I’d read it. Everything became clear on second reading. The more I read the story, the more I marvel at the intricate plot — I have no doubt that this was a difficult plot to pull off. On second reading, certain details will be discovered: The wolf who hasn’t left Eatem Hall at all, but who looks with freaky, shiny eyes upon the Pork-Fowlers’ car approaching the mansion.

The Kate Greenaway Judges suggest 7+ and I tend to agree. Picture books are increasingly difficult to sell for whatever reason, and there’s a temptation for publishers to market even the most sophisticated picture books to younger readers, sometimes turning quite difficult texts into board books, knowing that older children are being pushed into reading chapter books and novels exclusively. Please don’t push your young readers completely away from picture books! Buy them picture books as presents!

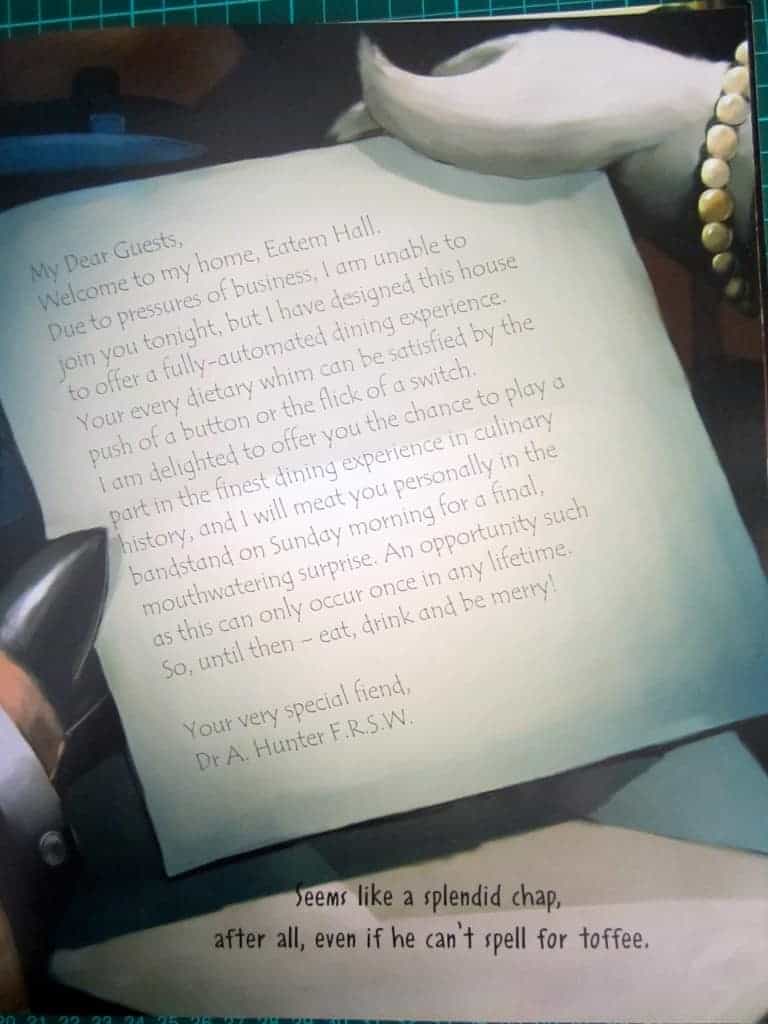

Intratext provides humour throughout:

In fact, reading the intratext is necessary, if you want to fully understand the plot:

Gradual Revelation Of The Baddie

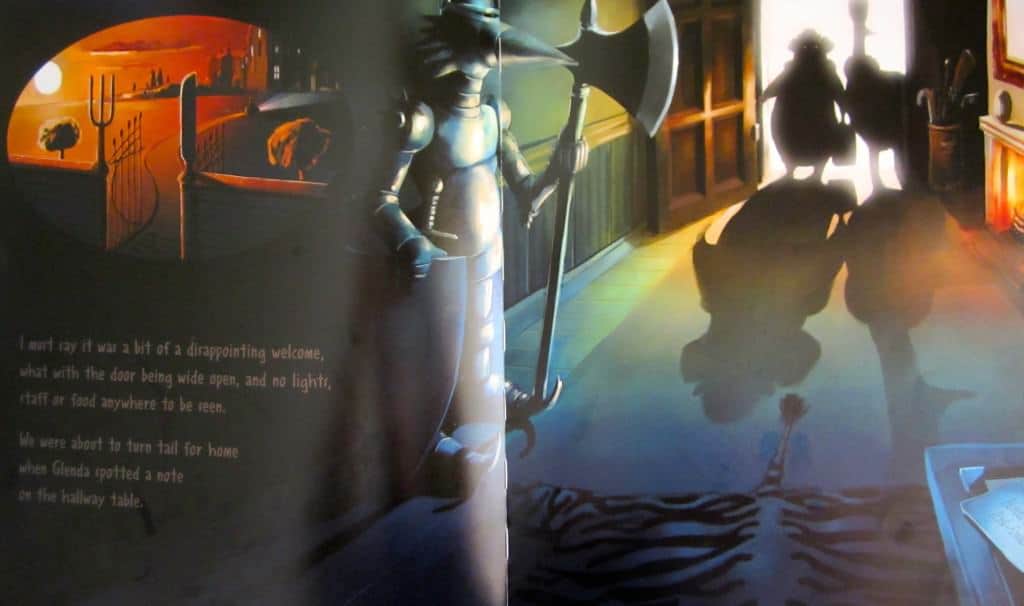

Especially masterful is the way in which the wolf is gradually revealed, body-part by body-part, to the reader. On the front cover we can see the wolf but only if we look very closely: He’s hiding in darkness to the left of the page. His fangs gleam. Unusual for wolves in picturebooks, he’s wearing spectacles. (This is a picture book about middle-aged characters — not a toddler, child or baby in sight.) The title page depicts a furry hand with sharp, white claws holding the invitation to dinner, though the reader doesn’t know what it is yet. Next is a second title page, brightly coloured, forming a double-page spread with the colophon. Most picture books don’t have two title pages, but this one helps to set the scene and is very much meant to be read: The reader now sees the wolf’s tail disappearing off the page. Wolves don’t like to be seen, especially when their motivations are nefarious. The next we see of the wolf is his shining eyes gleaming from a distant window, then, for the rest of the story, a Where’s Wally sort of game of ‘spot-the-wolf’ has been set up for the reader: Where is the wolf on this page? Where might he be hiding on this one? Sometimes the reader never knows — he might be inside the suit of shining armour. At other times, the reader is given enough clues to work it out — on one page he has poked the eyes out of a portrait and looks at his dinner guests through the wall. Interestingly, the reader never is given a good, clear view of the wolf. The best we get is a drawing of his face in semi-darkness under his pie-contraption, but this is enough. There is not ‘Aha! The wolf!’ surprise moment. The surprise moment for the reader comes only when the reader works out what the wolf is up to, and why he has not turned up for his own feast.

Wickedness Is Humorous; Each Side Is Balanced

The comic wickedness of the wolf (why doesn’t he just shoot them or bite them?) is amplified by the wonderfully naive and good-natured victims, who escape unscathed, none-the-wiser that they were ever in any danger at all. In fact, reading this book feels like watching Road Runner: You don’t know which side to root for. After all, the coyote needs to eat. And the road runner seems to take so much pleasure out of foiling the coyote you almost want him to get caught. This story is an inversion of that: The Wolf is obviously very smart, and the Pork-Fowlers are sinfully greedy. Each side is evenly matched in avarice.

Dramatic Irony

Children love to know things before the characters do — perhaps we all do, so long as we’re not presented with fools for protagonists. The naivety of the Pork-Fowlers achieves this feeling in the reader, as well as providing for a happy ending. Note the body language of Glenda, who offers a friendly wave to a pack of wolves who have turned up to eat her:

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

This is a book with a strong sense of place: Think of that wonderful series from the 1970s, To The Manor Born. This story is the picture book equivalent, set in rural England where old money live luxurious lives to varying degrees. Though the Pork-Fowlers live comfortably in a cottage-like house, the real wealth resides with the wolf, an eccentric aristocrat who lives in a gothic mansion from the old world.

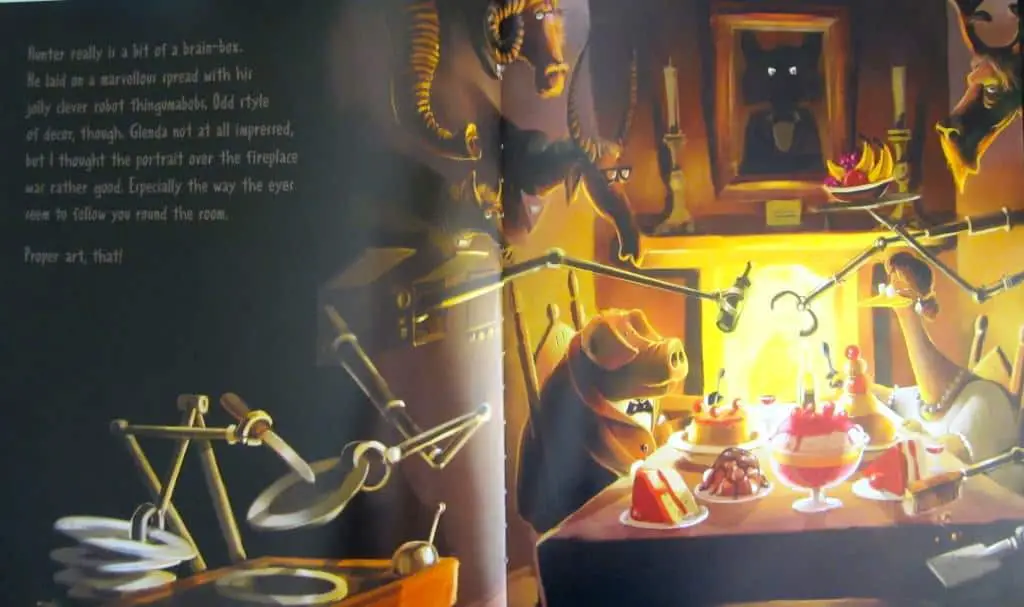

The time period is less clear, but could well be set in the 1970s or 1980s — the contraptions built by the wolf have a steampunkish vibe. He listens to music on a gramophone but has a room full of CCTV set up. Technology in picture books is often an anachronistic mixture of things and, if the book is good, matters not a jot. Perhaps this is set in 2004, with the wolf still living in ‘the past’.

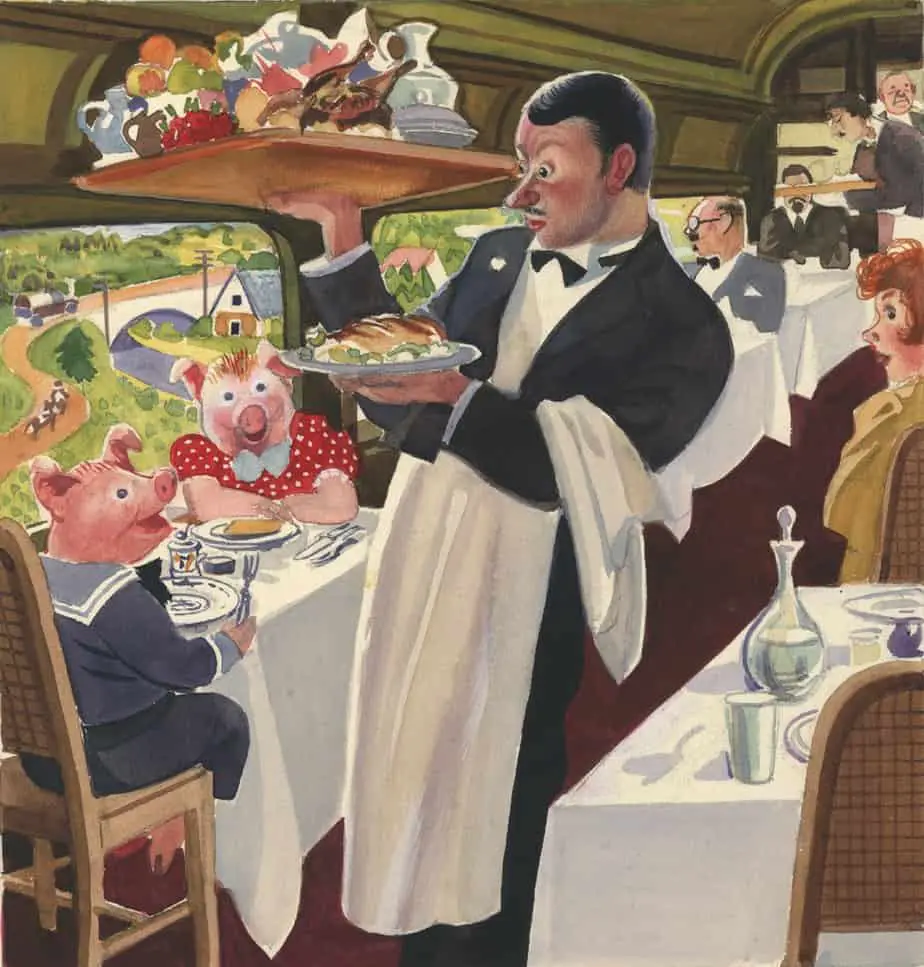

The cover is a combination of dark and warmth, with the sun setting behind the Pork-Fowlers as they drive into a dark forest. The pages themselves are a mixture of cheery brightness and ominous dark. The Pork-Fowlers are not only happy and naive — their kitchen scene is filled with light and joy. The cheerful kitchen scene is filled with humorous details: Ham Jam, Mr Pork-Fowler reads a newspaper called The Hog. One of them has used a knife to spread jam then plunged it back into the butter, in a piggy display of happiness and greed. Then, of course, is the fact that we are looking at two animals behaving like people, though we’ve seen this so much in picture books now that it has probably lost some of its humour — the humour must come from elsewhere.

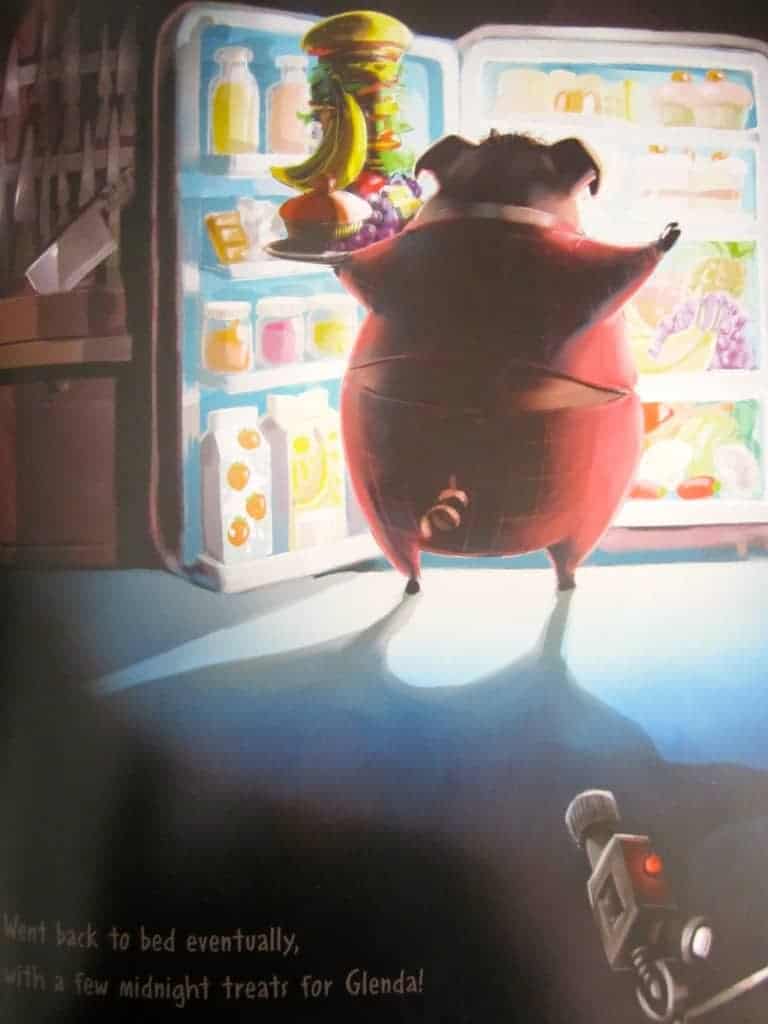

Food is important across children’s storytelling in general, but pigs and food are particularly well-suited. If you see a pig in a picture book, they are almost certainly enjoying their food.

Use of Light and Dark

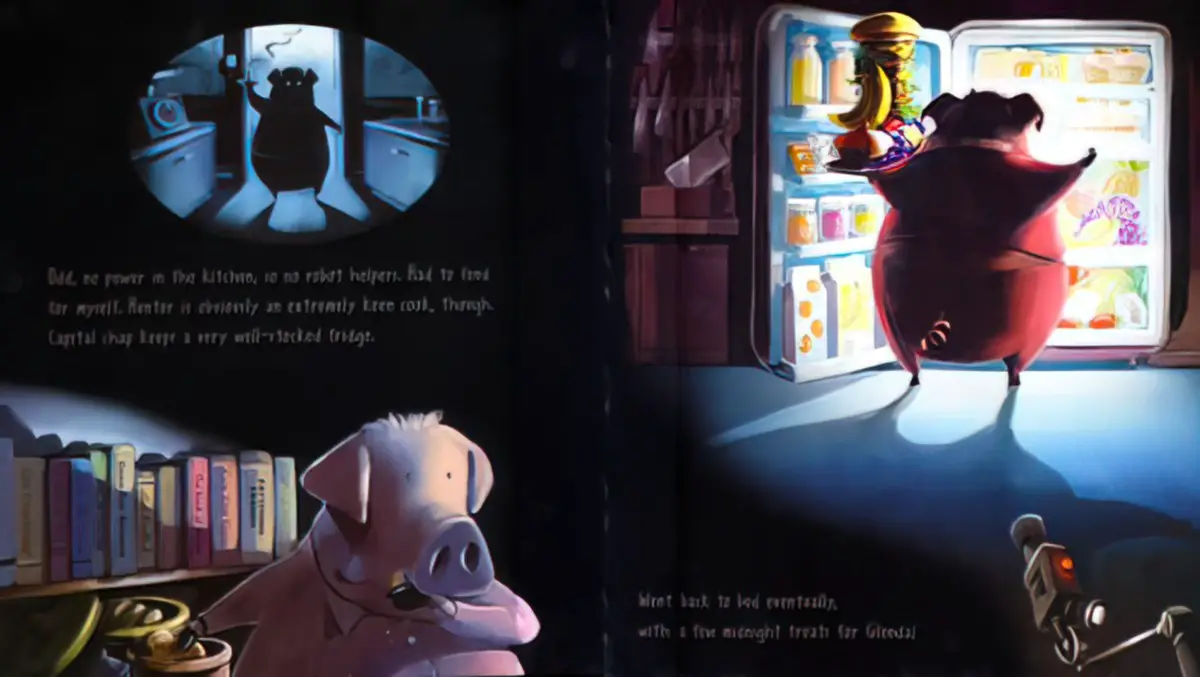

Apart from the light-dark contrast between the happy Pork-Fowlers’ cottage and the gothic darkness of Eatem Hall, we usually see the light-dark contrast in a single page. Lightness follows the Pork-Fowlers around.

Of course, some sort of light-source is necessary when illustrating a dark, gothic room, but the light is always positioned near-to and highlighting the naive dinner guests, with the brightness serving as a symbol of innocent utopia. Note that Mr Pork-Fowler’s bulky shadow bleeds into the darkness of the mansion. His greed may well be his downfall. (With pure dumb luck, it isn’t.)

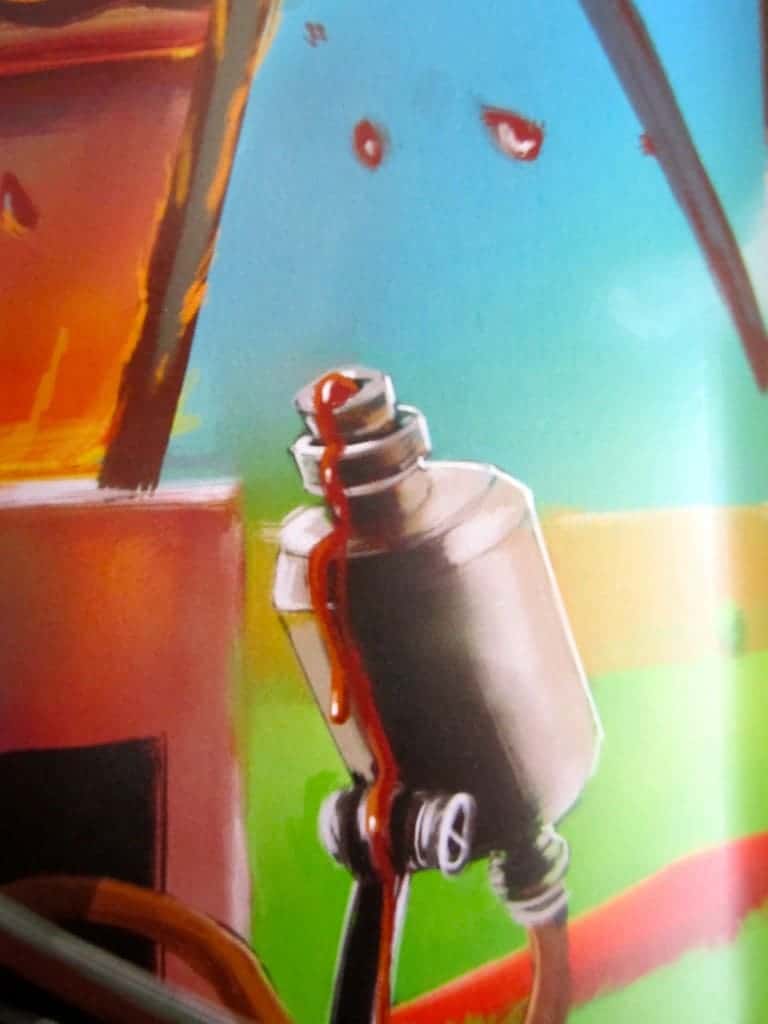

Hints Of Bad Things To Come

Like an Anthony Browne forest scene, there are slightly surreal and comical hints that there will be blood:

STORY SPECS OF GUESS WHO’S COMING FOR DINNER

This is a generously sized book at 10.2 x 0.4 x 11.7 inches, published by Templar Publishing in the UK. Here are their other picture books. It’s worth checking them out if only because they don’t seem to have any ‘Picture Book Superstars’ on their list (you know, Lemony Snickett, Jon Klassen, Oliver Jeffers, Julia Donaldson), though you will recognise a number of names.

Published in 2004, GWCFD was shortlisted for the 2005 Kate Greenaway Medal.

Horace and Glenda Pork-Fowler take up an invitation to enjoy a weekend’s hospitality at Eatem Hall, and only narrowly escape being on the menu themselves. The dead-pan text contrasts with the illustrations: children love looking for the visual clues which suggest the pantomime fate which awaits the weekend guests. A very distinctive book which works fantastically with children.

Judges’ Commentary

This is a beautiful production in all respects but I do wish it had been printed on matte paper. If ever there was a case for matte paper in a picture book, this is it. With its dark pages and quite dark text, the book must be positioned just right if reading before bedtime in winter under artificial light.

COMPARE WITH

Another fictional animal character who ‘lives to eat’ and takes great delight in food is Winnie the Pooh.

For hints of bad things to come, see a picture book by Anthony Browne, such as Hansel and Gretel, in which the trees look like gnarled creatures. Into The Forest is similar, with the boy’s worry symbolised by the legless soldier statue in his bedroom, or the lightbulb over the dining-room table that seems to be melting into tears.