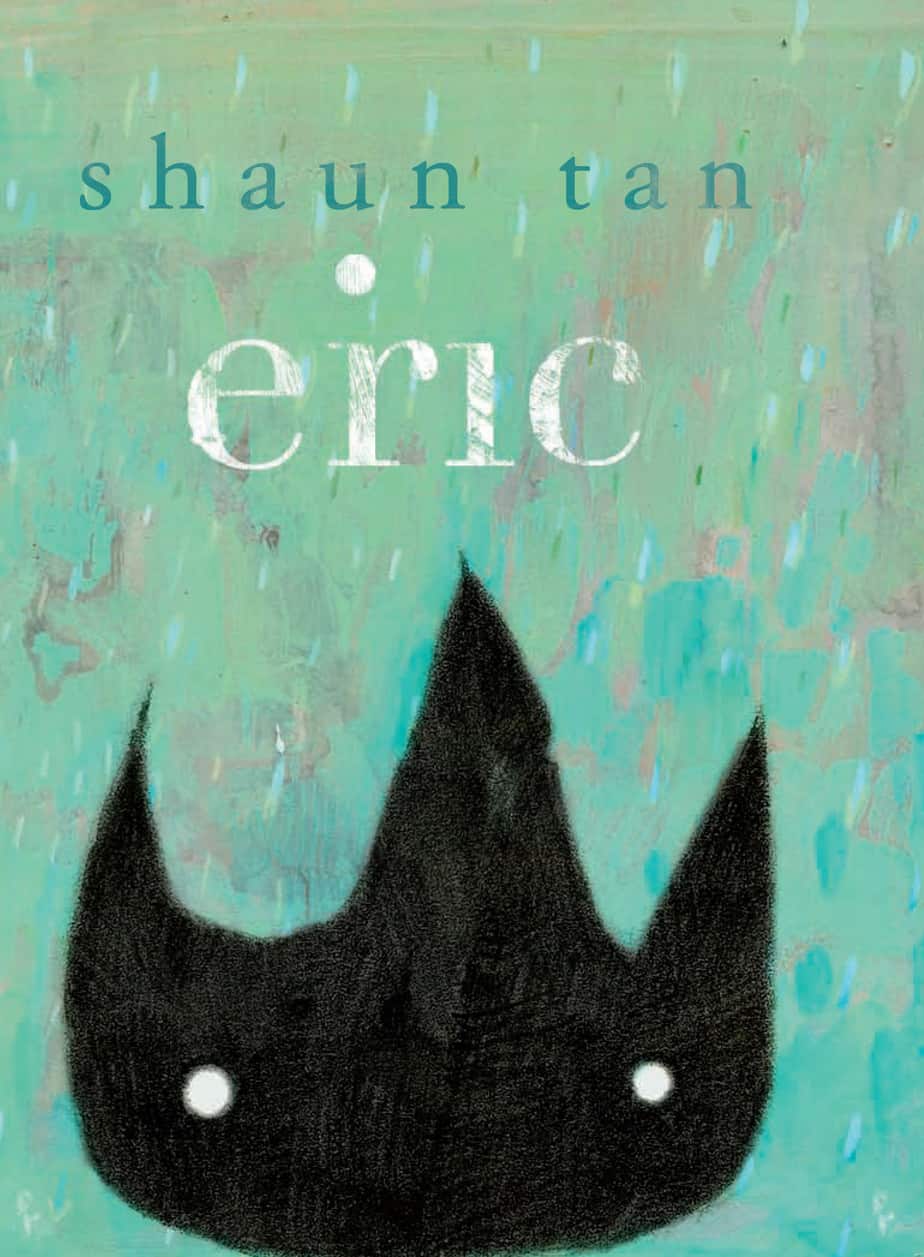

Eric is a miniature, post-modern picture book by Australian author illustrator Shaun Tan. This simple story says big things about cultural difference.

The character design of Eric looks to me a little like Vertebrae C6, which could lead me in the direction of an absolutely ridiculous reading, but we shan’t be doing that today.

NOTES ON THE COVER OF ERIC

Eric’s cover is inviting; the embossed title and author are both prominently displayed, taking about a third of the already small space. Yet even here there is playfulness and subversion. There is no capitalisation on the page, and the dot of the ‘i’ in ‘eric’ has been displaced, appearing slightly to the left above the ‘r.’ Already, we have the implication that not all the rules will obeyed, and that Eric himself is a little different. This idea is reinforced by the image on the cover. Against the mottled green background suggestive of Eric’s jungle origins, Eric peeps up, dominating the lower half of the spread whilst remaining intriguing and inviting the reader to look further.

Unlikely Normal

A similar cover layout is used on the Judy Moody covers by Megan McDonald:

Another author whose books often avoid adult-like punctuation such as capitalisation is Lauren Child, whose own name is known for being lower case, like bell hooks:

For artists who eschew capitalisation of their names, it’s often because they are making a statement against prescriptivism, and the rules set down by adults. The practice may also symbolise rejection of the ego.

THE MINIATURE

Only in picture books do you regularly find the size and shape of the book itself has something to do with the content. This green version of Eric is only about as big as your hand.

Notice the peanut: Eric uses a peanut for suitcases. We see the peanut again at the end of the story, with a single peanut on a dinner plate. Surely the family isn’t suddenly eating peanuts for dinner? What is the significance of this?

Since the peanut was used as a suitcase, the peanut now stands in for travel and foreignness. The family’s own dinner may now feel foreign to them, now that they’ve had a glimpse of another culture. The peanut is of course used commonly in the West to symbolise the miniature, further linking the peanut to Eric. When set upon a dinner plate, its small size is emphasised. I don’t believe the family is really eating a peanut for dinner. I believe the peanut is a symbol.

Eric is included in the (full size) Shaun Tan collection: Tales From Outer Suburbia. However, just as an anthology of Beatrix Potter stories doesn’t do justice to the individual tales compared to the individual, child-sized editions, Eric is best experienced in miniature, as I’m sure it was designed to be read. Page breaks and publication size are more important than sometimes given credit.

Hannah Love explains the significance of the page breaks:

The first page has no picture, and indeed Tan never places words and pictures on the same side of the gutter; the spreads may be two images, two paragraphs of narration, or text on one page and image on the other. This separation fully emphasises the two different stories and the division between them, and even creates comic effect in places, such as the account of Eric studying displayed opposite a picture of the tiny Eric having to stand on the book in the middle of his page to read.

Unlikely Normal

Eric is similar to The Lost Thing (written and illustrated by the same author) in that:

- The narrator is a first person character, though off stage in this story

- It’s set a number years in the past, with the storyteller looking back

- The main character is a strange creature who comes from another place/time/dimension, who disappears before the end.

- The narrator wonders if this strange creature is happy.

- The creature in this story is interested in small things whereas the boy in The Lost Thing is the one who is the noticer. (Noticing this creature is a noticer is itself a form of noticing… mise en abyme.)

- Behind the doors, in the darkness, is a world full of interesting artifacts.

- The narrator is encouraged at the end to wonder what it all means.

ERIC AS A POSTMODERN PICTUREBOOK

What is a postmodern picturebook?

Eric may not seem like a typical postmodern picture book. It is tiny (15cmx12cm) in comparison to many of its counterparts, lacking the large double spreads that allow for hugely detailed drawings. Yet on closer examination, the book’s inter-relationship of text and image is as complex as its contemporaries; being playful whilst simultaneously breaking boundaries. With the combination of a matter-of-fact narrative and endearing pencil drawings of the diminutive aspects of Eric which are never mentioned in the text, Tan effectively explores issues of identity and cultural difference. Grigg (2003) claims that visual images create bridges between cultures and languages, and Tan plays with this idea, showing how determination to appreciate our own culture can be detrimental to acknowledging the culture of others, a particular danger in a multicultural society. He defines Eric as being about a kind of misunderstanding and cultural miscommunication. According to Tan, the character of Eric is based on a combination of a foreign guest that Tan had to stay, and his own budgerigar. This creates a book that opposes … speculation that modern life undermines childhood as a time of play and engaging with the natural world. Eric and his fascination with the world around him show a childlike innocence compromised by an adult narrator who is baffled by and unable to fully interact with his/her guest.

Unlikely Normal

STORY STRUCTURE OF ERIC

The main character is the storyteller narrator.

SHORTCOMING

This kid (I assumed it is a boy, but she could just as easily be a girl) is overconfident about her ability to explain her world to a newcomer. She feels she knows her own world very well. But her Shortcoming is that she can’t possibly know her own world until she experiences someone else’s.

Because what is her point of reference?

DESIRE

She is looking forward to teaching an exchange student everything about her local environs. This will make her feel like an expert. She will feel heard. She will feel important and useful.

OPPONENT

Eric, however, is not on the same wavelength at all. He asks her questions that simply can’t be answered. This means she doesn’t get to feel like the expert anymore. She never predicted these questions. She didn’t realise there was anything odd about things which are, to her, banal.

Eric the exchange student, I believe, is a metonym for ‘foreign culture’.

PLAN

Shaun Tan tends to be very specific about the plan part of his narratives:

I had planned for us to go on a number of weekly excursions together, as I was determined to show our visitor the best places in the city and its surrounds.

Despite the past participle, they did go on these excursions, but while the narrator wanted to show Eric the local landmarks, Eric was only interested in little things. For example, at the zoo, Eric sees only the elephant’s foot. This reminds me of the parable The Blind Men And The Elephant.

“The Blind Men And The Elephant” was published in 1873 as part of a collection of rhymes and poems by John Godfrey Saxe. Saxe (1816-87) baed his moral tale — more of a parable in the guise of a rhyme — upon a story of Indian origin that he called a ‘Hindoo Fable’. It is probably quite ancient in origin, as similar tales are told in other religions, including Buddhism, Sufism, Islam and Jainism. In each, the number of blind men varies and sometimes they are not blind at all, but men in a darkened room with an elephant (clearly the only elephant in a room not to be ignored). The Hindu version of the tale goes something like this:

One day three blind men met, as usual, and sat under their favourite tree, talking about many things. All of a sudden, one of them said, ‘I have heard that an elephant is a strange creature.’ Another replied, ‘Yes, it is too bad we are blind and do not have the good fortune to see this strange beast.’ But the third said, ‘Why do we need to see? Just to feel it would be wonderful.’ At that moment a passing merchant with a group of elephants came conveniently along and overheard their conversation. ‘You fellows,’ he called, ‘if you really want to feel an elephant then come with me.’ The three blind men were surprised but very happy. Taking each other by the hand, they quickly followed the merchant and began to speak excitedly about how the animal would feel and how they would form an image of it in their minds.

When they reached the elephants, the merchant told two of them to sit on the ground and wait while he led the first man to one of the beasts. With an outstretched arm, the man touched one of the elephant’s front legs and then the other, stroking each from top to bottom. ‘So’, he said, ‘the strange animal is just like that.’ Then the second man was led to the elephant. With an outstretched arm, he touched the creature on the trunk, stroking it up and down and from side to side. ‘Ah! So now I know, I truly know!’ he cried. The third man encountered the elephant’s tail and wagged it from side to side. ‘That’s it,’ he said, ‘now I know too.’

The three blind men thanked the merchant and returned to their spot under the tree, each one excited about what he had learned. The first man said, ‘This strange animal is just like two big trees, without any branches.’ Luckily, he was unable to see the expressions on his friends’ faces, for they were horrified. ‘No, no!’ they cried in disbelief at what they had just heard. The second man then said, ‘This animal is like a snake, long, strong and flexible.’ ‘What!’ exclaimed the third man. ‘You are both quite wrong. the elephant resembles a fly whisk, swishing from side to side.’

They argued about this for days, each insisting that he alone was correct, and of course, as Saxe points out in the conclusion to his rhyme — all three of them were partly in the right / and all of them were wrong. The moral is that nobody can claim to fully understand a subject until they have grasped — in this case, quite literally — the whole thing. Even then, it is never possible to know the full truth about something, simply because everyone, however knowledgeable or experienced will view it in a different way. Hence, on a deeper level, the elephant can be seen as reality, and we are all the blind men, each of us able to perceive only a tiny part of a much greater whole.

Pop Goes The Weasel: The secret meaning of nursery rhymes by Albert Jack

Blind Men & An Elephant: People assume their experiences are a representative sample of the universe, and thus base their assumptions about reality on a few meagre impressions. They shrink the world to fit their minds and think they’ve expanded their minds to grasp the world.

@G_S_Bhogal

In short, I believe Shaun Tan has chosen the detail of the elephant’s foot in reference to this ancient parable, turning Tan’s contemporary story of Eric into a parable as well, though its moral is less clearly spelt out: Our own countries are our own separate pieces of the elephant.

This intertextual detail is followed by ordinary, more relatable ones: At the casino Eric gets onto the table and looks at a chip. At the movies he is taken by a dropped piece of popcorn.

BIG STRUGGLE

I might have found this a little exasperating, but I kept thinking about what Mum had said, about the cultural thing. Then I didn’t mind so much.

The Battle is with herself — between the self that wants to show Eric everything she knows, and the self that’s open to learning from the foreigner.

We see more of this psychological big struggle at the dinner table when ‘There was much speculation over dinner later that evening. Did Eric seem upset?’ and so on.

ANAGNORISIS

In Shaun Tan’s work, Anagnorisiss are often accompanied by images of doors and windows.

In this particular story we see Eric fly out the window on a leaf and flower sail.

It actually took us a while to realise he wasn’t coming back.

The window, however, comes before the Battle scene.

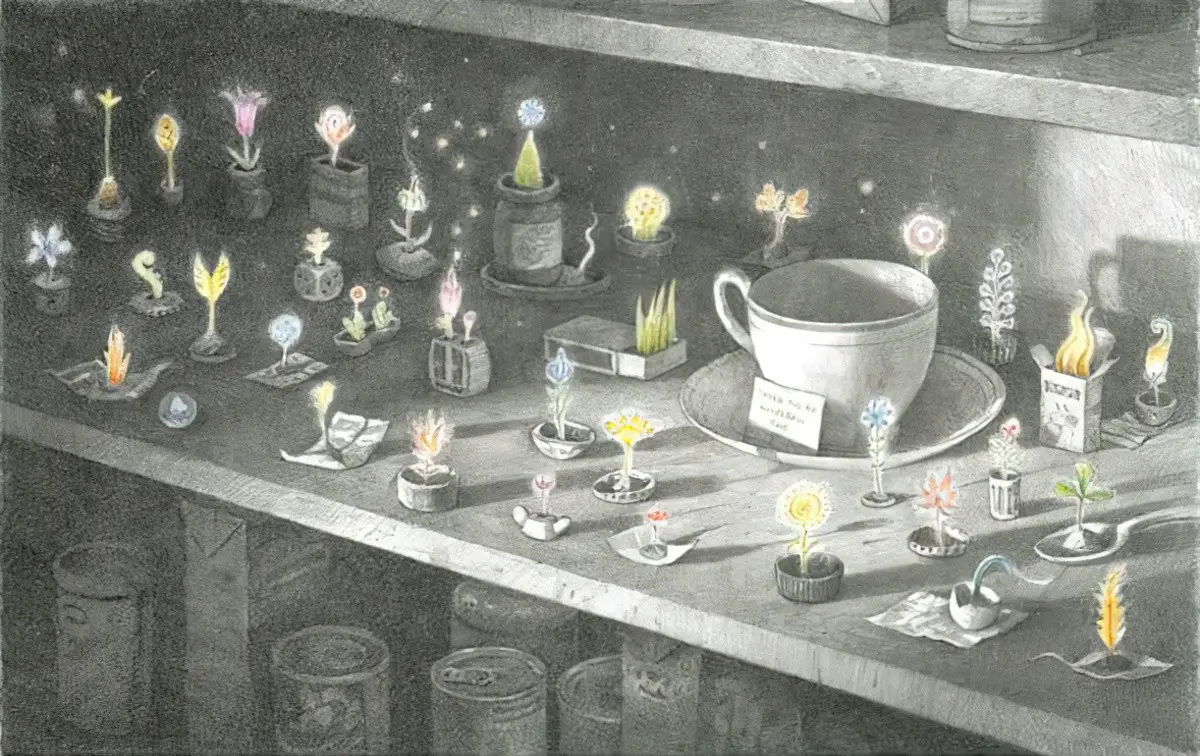

So in this case we have a door: the pantry door functioning as symbolic anagnorisis. Always look at whether a door is open or shut, because the meaning is highly dependent upon that.

NEW SITUATION

Although Eric has gone for good, he has left as a gift a different worldview for his host family. They will never see their own environs in quite the same way, ever again. They’ve seen another piece of the elephant.

This is the reason often cited for hosting exchange students. Other people think they’re doing an exchange student a favour by hosting them, without anticipating the benefits they’ll derive themselves.

Shaun Tan, in this picture book, has conveyed these two views with poignancy.

SEE ALSO

Another story with fetching illustrations of a very small character living in a human-scale world is Little Tom (1922).