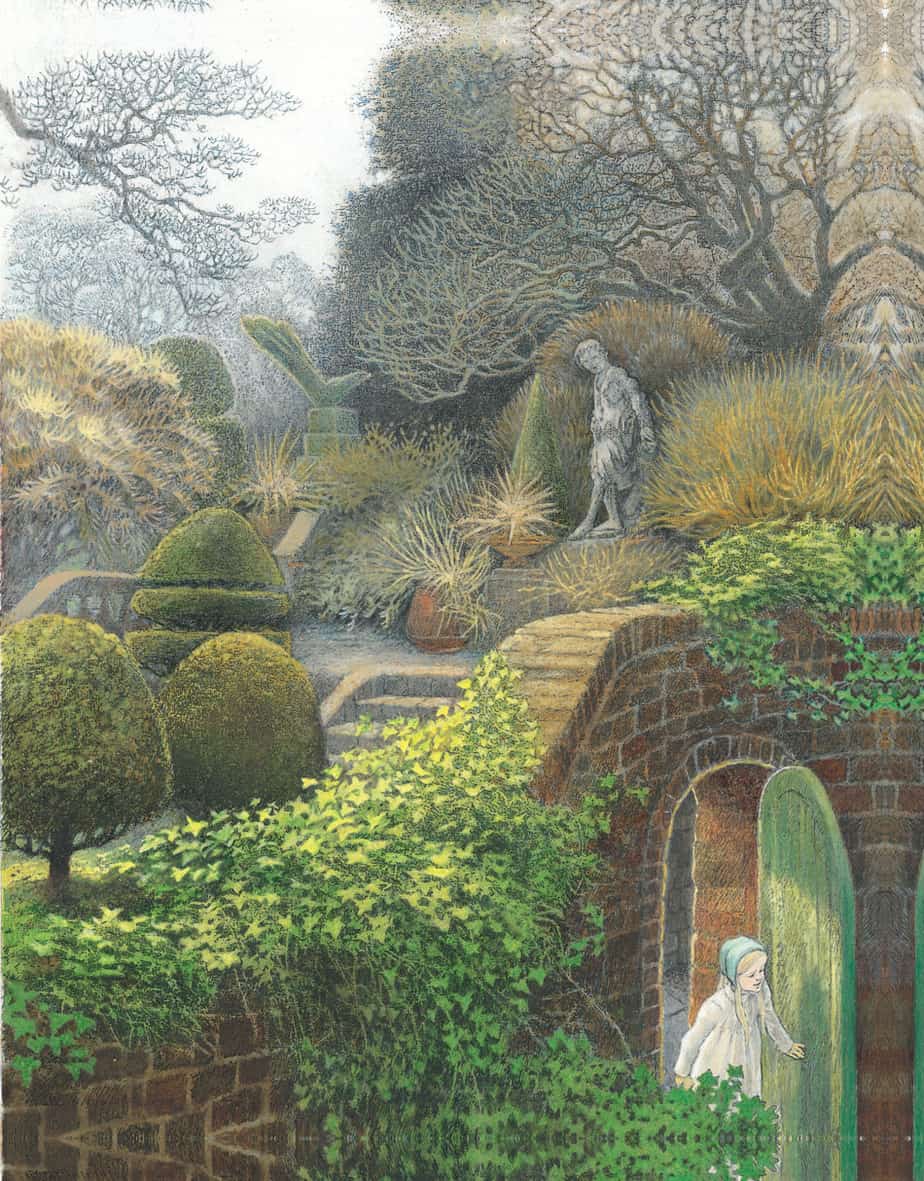

The Secret Garden

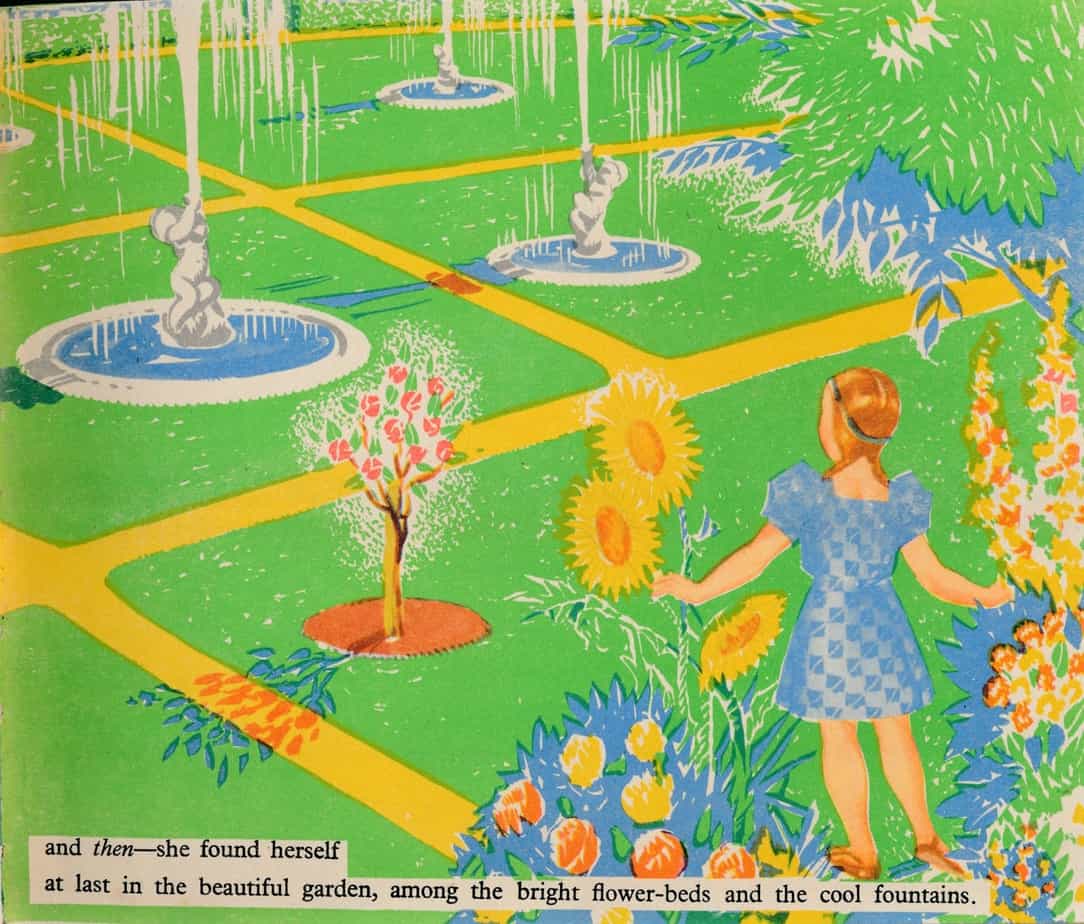

This is perhaps the most famous, and certainly the most analysed, of the English country gardens in children’s literature.

Below is an illustration by the wonderful Inga Moore, also well-known for her illustrations of The Wind In The Willows. Though Inga Moore is a modern illustrator, her style has a classical style which you might almost expect to have been published with the originals.

Inga Moore is unexpectedly Australian, though these very English landscapes make more sense once you learn she was born and in and moved back to England.

Jerry Griswold writes about The Secret Garden in this post, talking mainly about ‘snugness’ (which I refer to as ‘hygge‘).

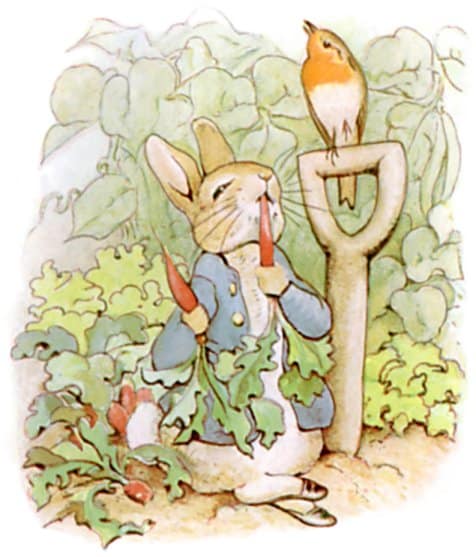

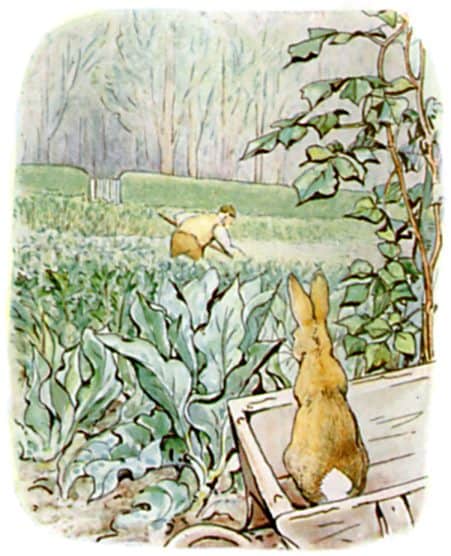

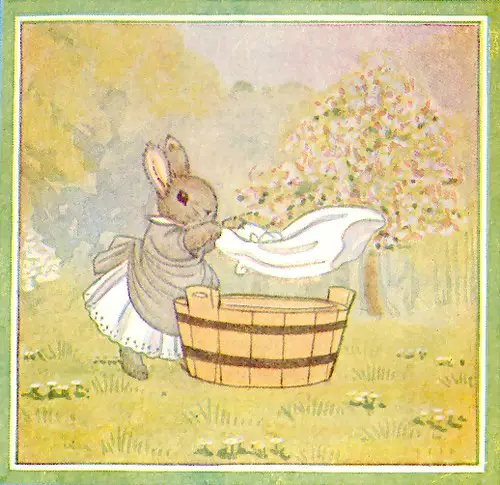

Beatrix Potter

Here is my post on Peter Rabbit.

Mr McGregor’s Garden is the most perfect vegetable and flower garden ever seen — its vague topography makes it one’s idea of what an old-fashioned country garden should be. The interesting adventures that Peter Rabbit had there have, at first sight, a familiar moral basis of filial obedience, but that is not what one remembers them for; it is the rural magic, the delicate beauty of the pictures, the few words, precise and perfect, that describe them, and the idealised view of the longed-for North Country of Beatrix Potter’s childhood holidays to which she eventually returned.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Allison Uttley

Blount continues: The work of Alison Uttley has many of the same strains as Beatrix Potter. There is the same Northern countryside, populated exclusively by small animals living their lives in holes, burrows and tiny houses. These books were published from 1929 onwards.

- fire from wood

- water from the well

- candles made of rushes

- a village community

- a magic truce is observed at all times: no predators, no marauders, Wise Owl does not catch mice, the Rat only steals a few provisions and makes up for it by giving unexpected presents.

- sometimes the animals talk in baby language

- even the adult characters have childlike qualities

- female adults are old enough to keep house and cook but young enough to enjoy games, tricks and picnics.

- At Jonathan Rabbit’s school lessons are about flowers and nursery rhymes.

- elements of folklore and animal fairy tale — the animals have magic that humans have lost

- There’s a nearby woodland which might be based on Shere or Finchingfield or Tunbridge Wells but with tiny ‘doll’s house improvements which make this kind of art so satisfying’.

There are no humans in these animal garden utopias because if humans were to appear, the illusion of magic would be gone for the reader. In Potter’s A Tale Of Two Bad Mice, there must be a human who plays with the doll house, but the story isn’t about when the human is there.

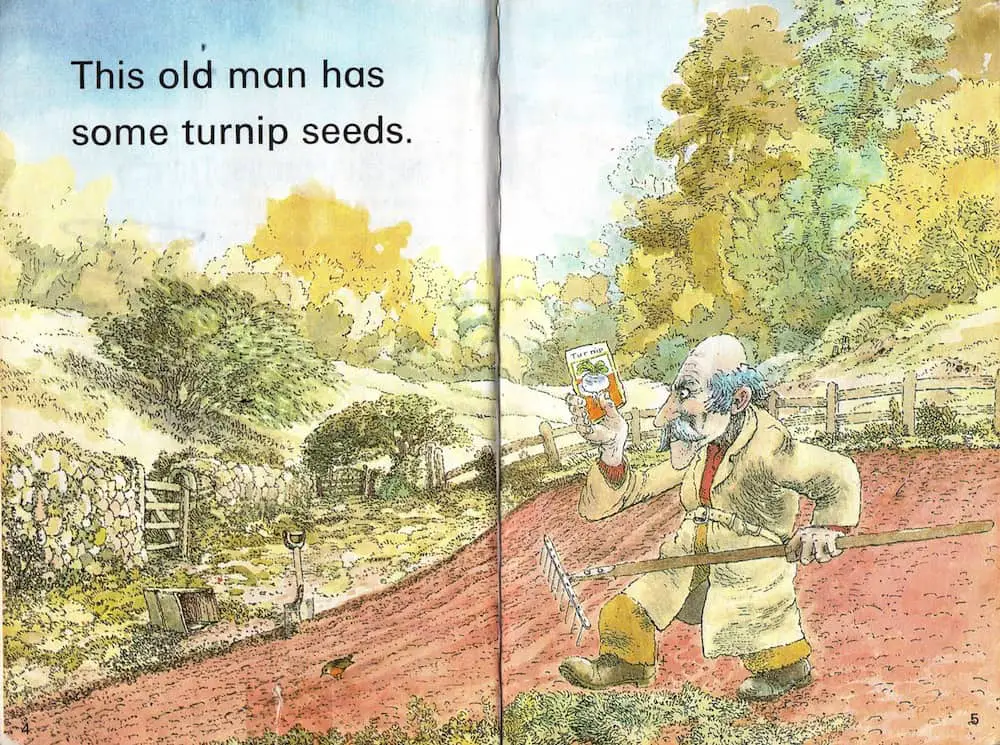

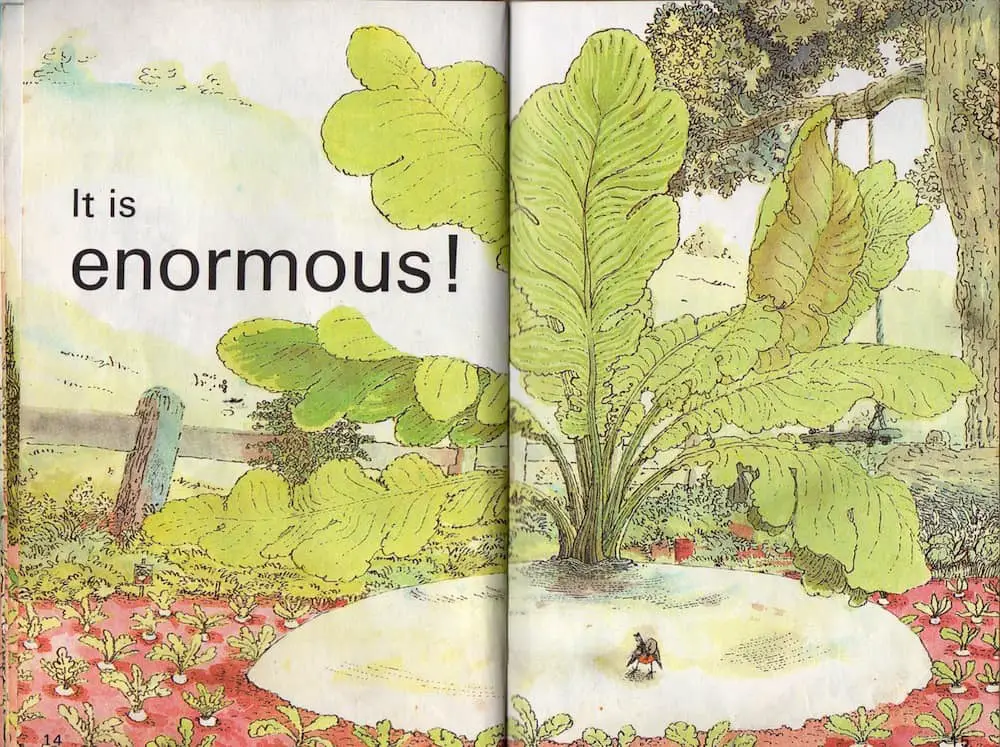

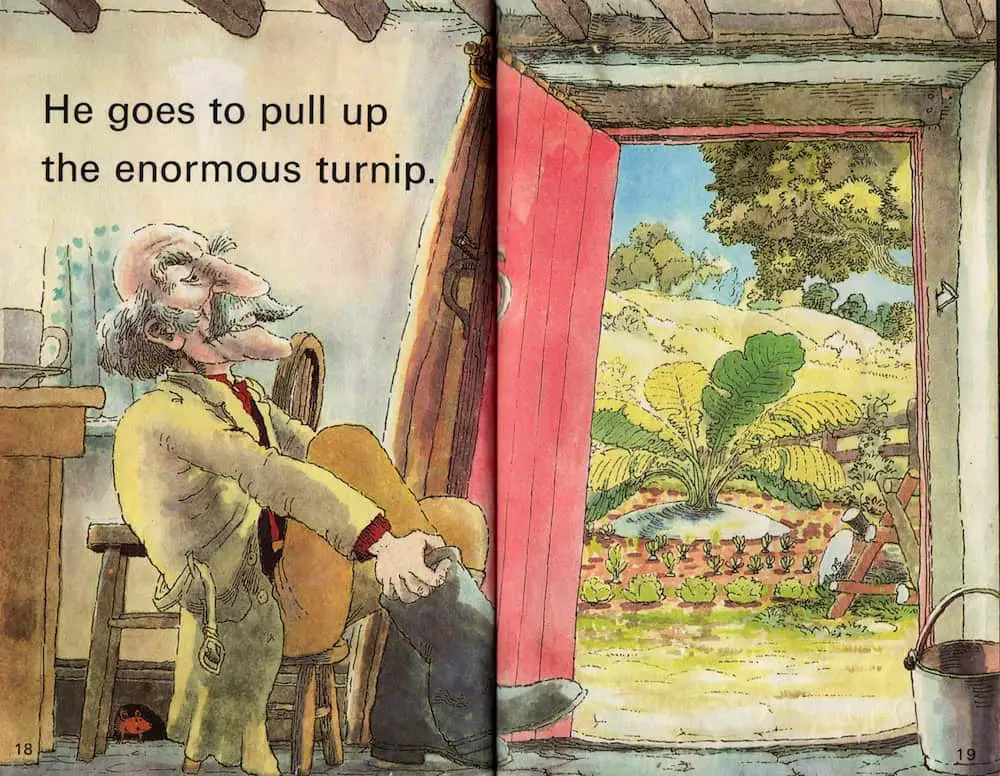

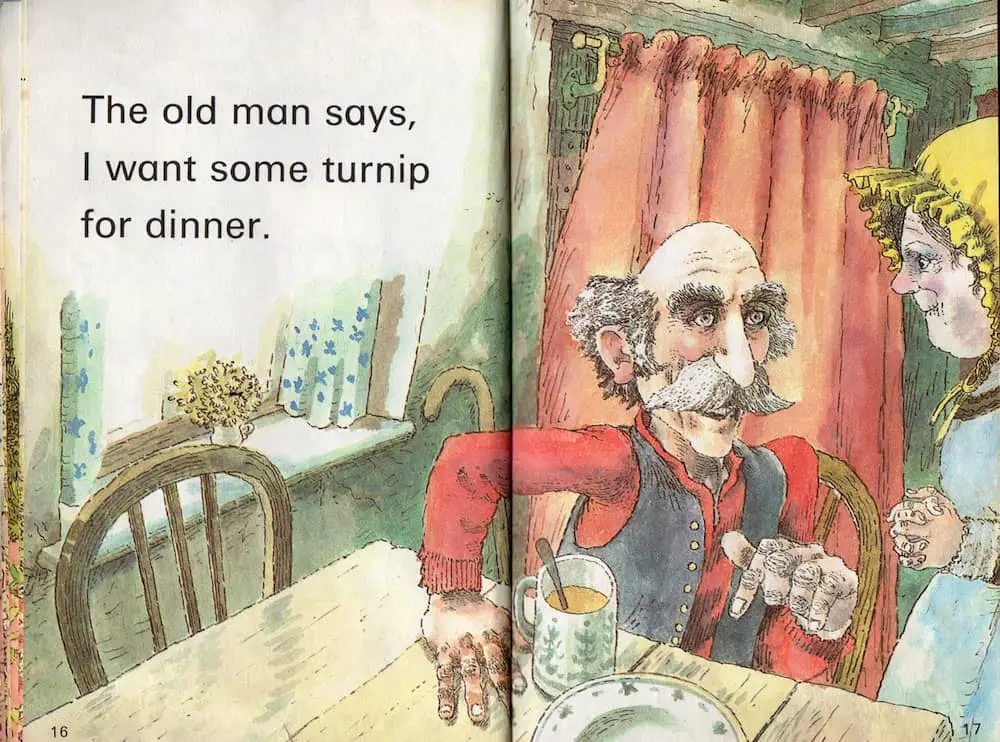

The Enormous Turnip

A garden always has the potential for surprises. If left alone, pumpkins and other root vegetables can grow huge. The gardener’s concern is, ‘What’s happening right outside, under the earth?’ Especially in earlier times when homegrown food was essential as a measure against starvation, this concern would’ve been much more.

A classic tale such as The Enormous Turnip is about that mindset.

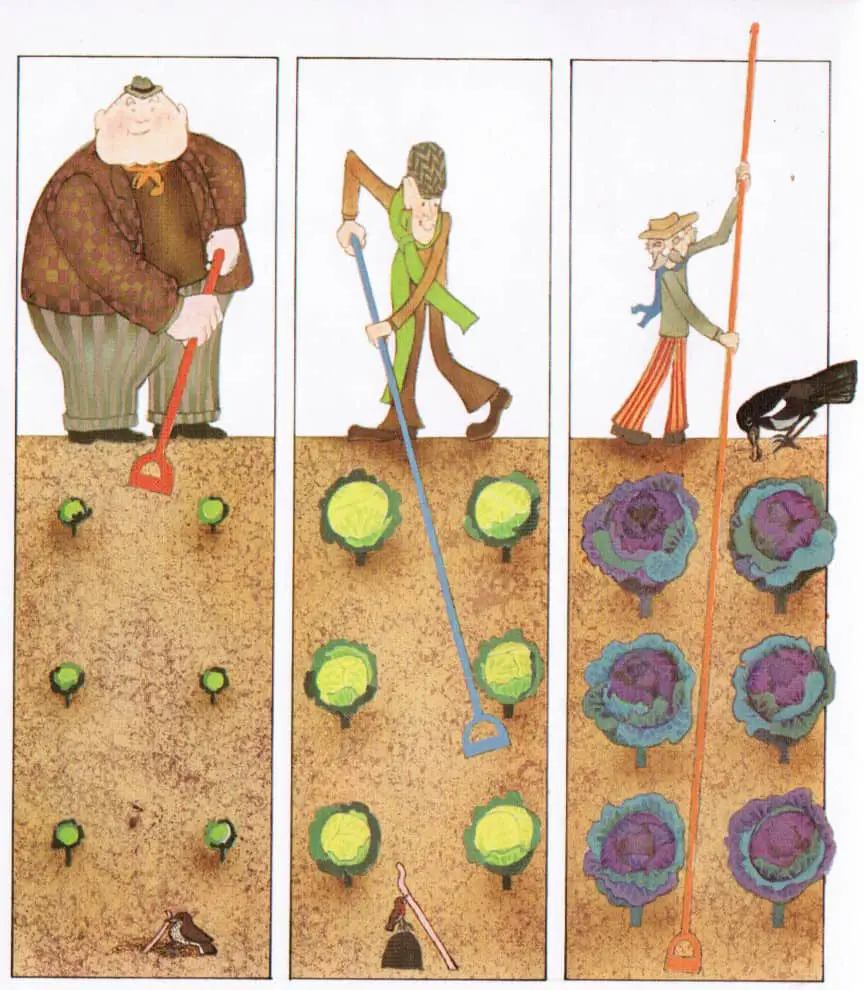

Here we see another English country garden illustrated by John Dyke for Ladybird. (Dyke also illustrated the Pigwig series.) There is a painter by the same name.

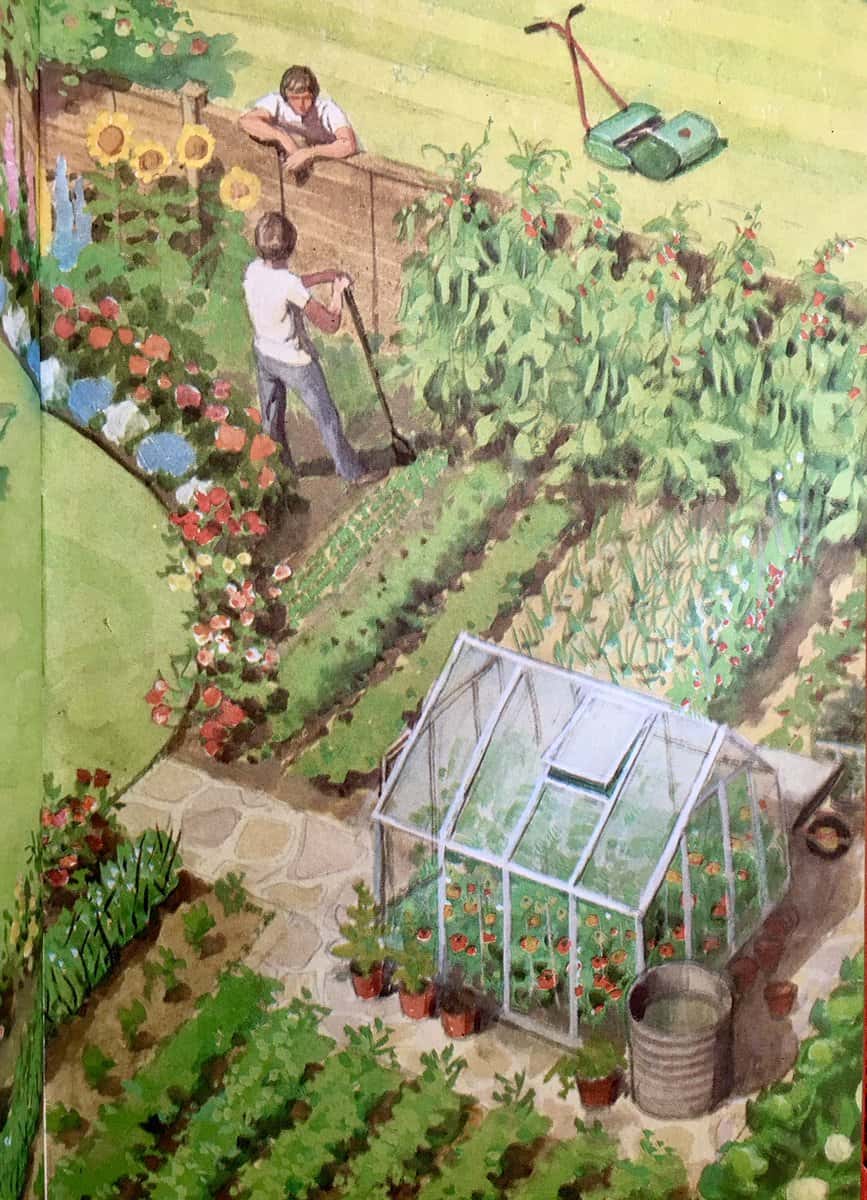

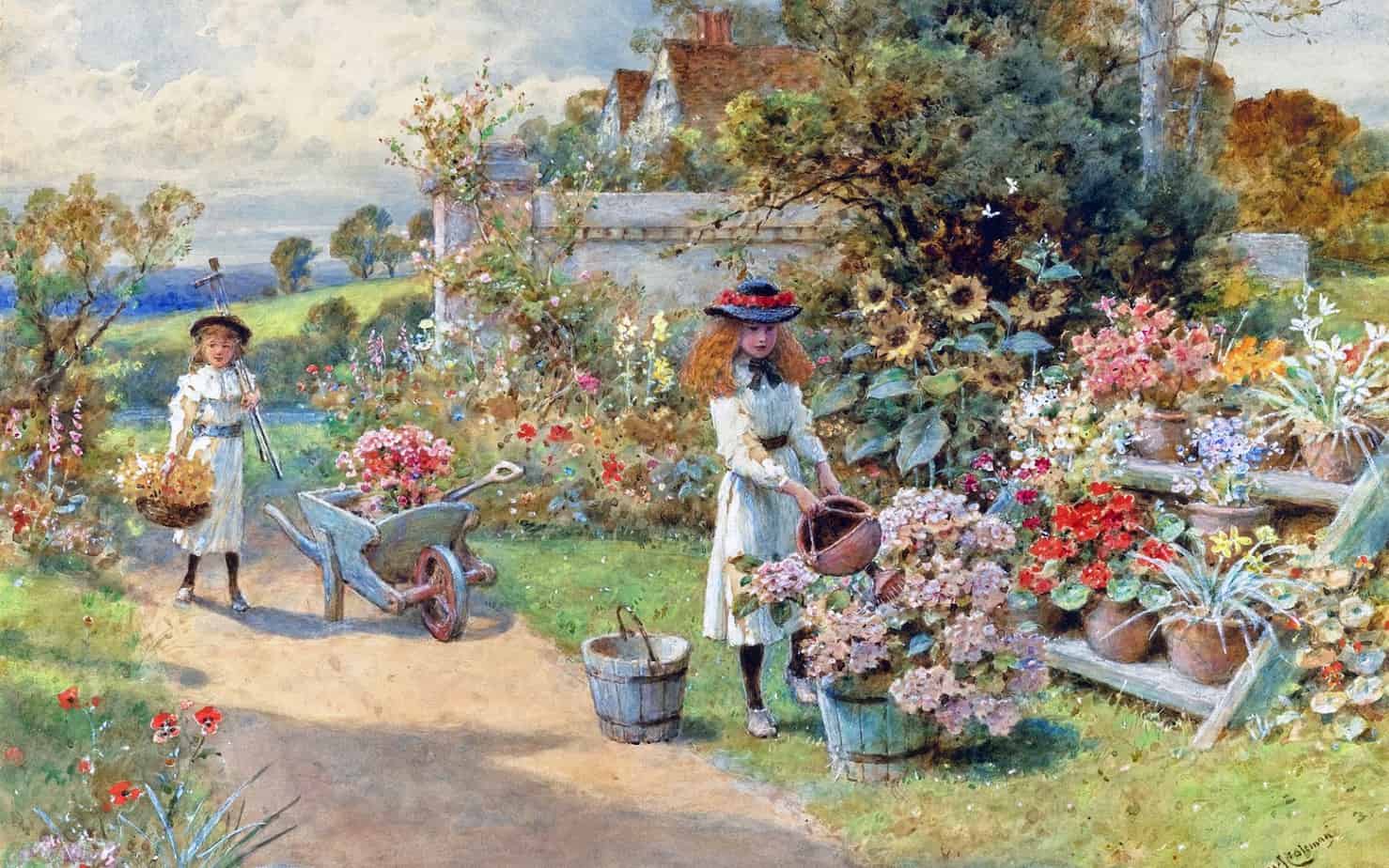

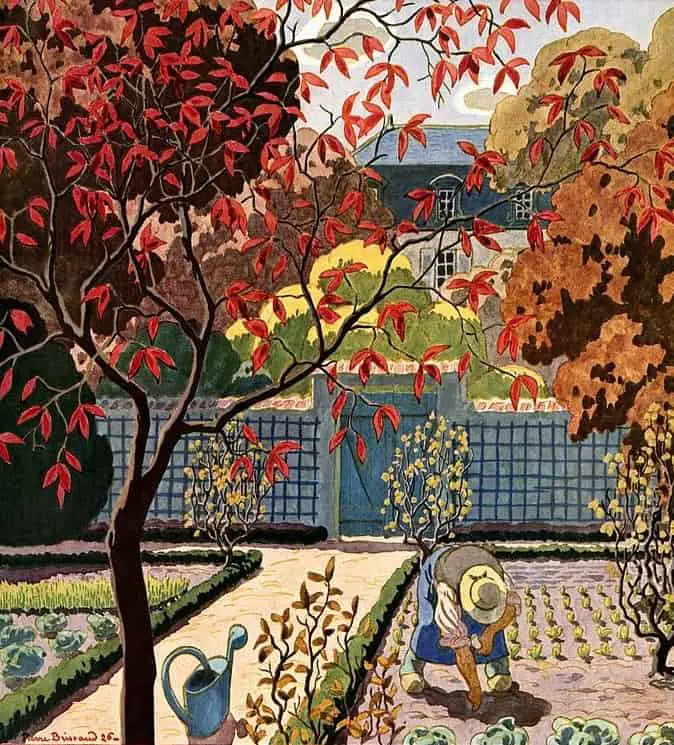

The English country garden includes robins, two beam fences, gates with cross bars, stone walls, undulating hills in the background and basic equipment like rakes, shovels and watering cans.

In an English country garden it is neither too bright nor too overcast, but just right for working up a light sweat.

from a Ladybird edition of The Enormous Turnip

from a Ladybird edition of The Enormous Turnip

Garden illustration-for Ladybird by Harry Wingfield

FURTHER READING

“I cannot say exactly how nature exerts its calming and organizing effects on our brains, but I have seen in my patients the restorative and healing powers of nature and gardens, even for those who are deeply disabled neurologically. In many cases, gardens and nature are more powerful than any medication.”

The NYT