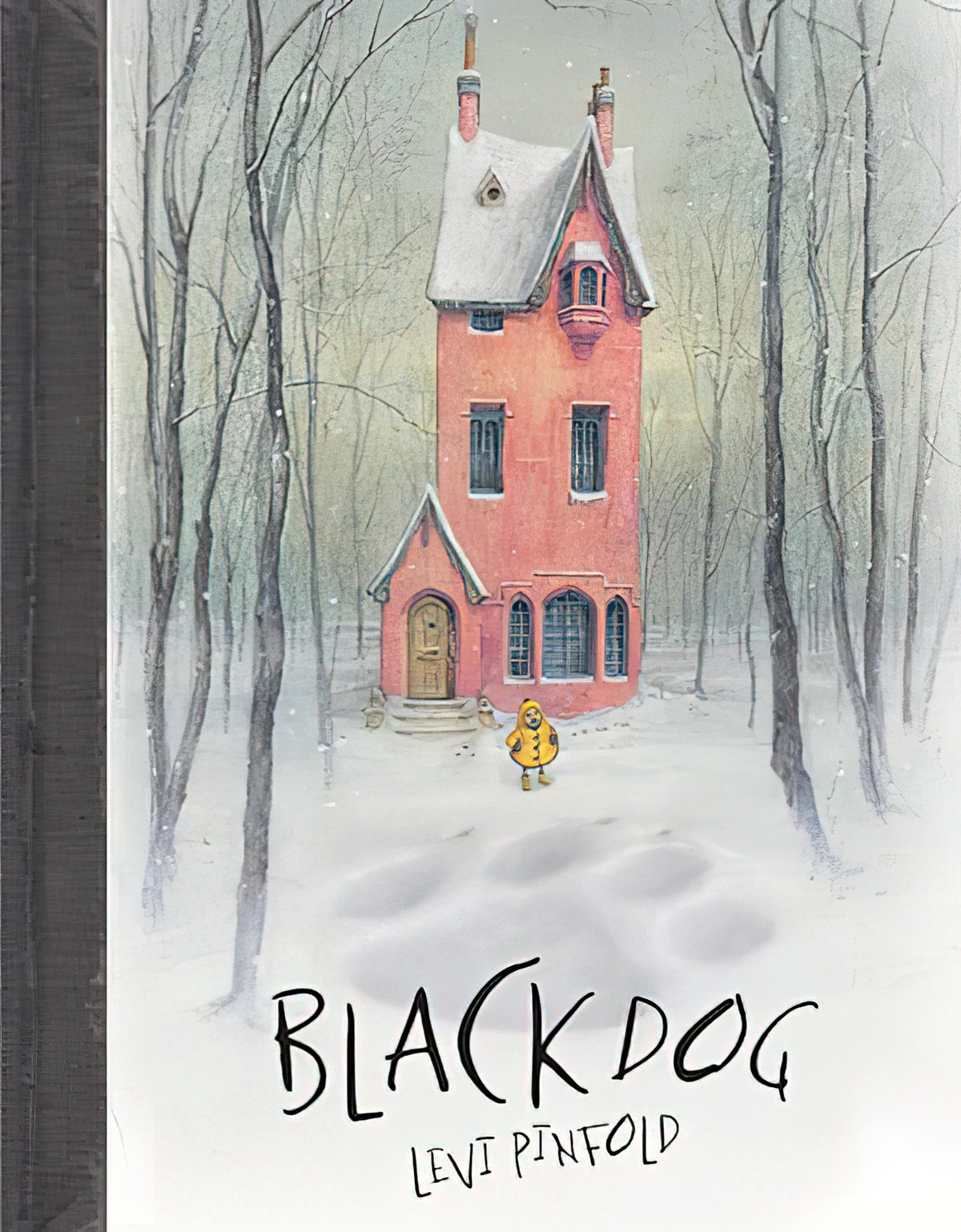

Throughout history, folklore has included stories of dogs who roam towns at night, especially in Britain. There’s Wiltshire’s Wilton dog or the fierce mastiff that roamed the streets of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Anyone who has ever seen a huge unfriendly dog standing right outside their glass door will know how frightening it can be. Pinfold takes that fear and now we have Blackdog.

A black dog is the name given to an entity found primarily in the folklore of the British Isles. The black dog is essentially a nocturnal apparition, often said to be associated with the Devil or a hellhound. Its appearance was regarded as a portent of death. It is generally supposed to be larger than a normal dog, and often has large, glowing eyes. It is often associated with electrical storms (such as Black Shuck’s appearance at Bungay, Suffolk) and also with crossroads, places of execution and ancient pathways.

Black dog (ghost) – Wikipedia

The illustrations are so beautiful in this author/illustrator picture book I suspected the story wouldn’t quite reach the same level. Readers will have varied responses to this, but for me, the story is structurally fine but the message problematic: Readers are taught to face their fears head-on, using the metaphor of a big dog outside the house. The problem is, I’ve been trying to teach my kid the opposite when it comes to dogs, as there are a lot of dangerous ones in our neighbourhood: If a dog looks scary, it probably is! I’m therefore left wishing the dog could have been some mythical, non-existent creature. The final scene shows a young child hugging the dog in a way that dogs should never, ever be hugged, as it’s a sign of domination, and little kids tend to be right at eye-level too. Even when picture books are to be read at the metaphorical level, we can’t forget that the literal level doesn’t suddenly cease to exist. So for entirely practical/safety purposes I do have a couple of issues with this book.

ALLEGORY AND SYMBOL

There may be a good symbolic reason for using a black dog, however, as the black dog has been used as a metaphor for depression and other mental illness, i.e. The Black Dog Institute. I have absolutely no idea if this were intended by the author/illustrator, but because of the black dog connection I can’t read this book as anything other than an allegory for agoraphobia/anxiety. (Update: I’m more sure of the symbolism since happening across the history of black dogs as metaphors of mental illness.)

Let’s look at Blackdog through this lens and see if it holds up.

Agoraphobia isn’t contagious insofar as I know, so it would be unusual for an entire family to be simultaneously terrified of going outside. For this reason, I’m interpreting the family as ‘different aspects of the same individual’, in much the same way as the Winnie-the-Pooh characters are each different facets of a child’s single personality. Sometimes this person looks out of the window and is not quite so scared — other days the size of the menace is overwhelming. But there is one small part inside this individual which has sufficient bravery to face the world. This is the classic mouse tale trope, in which the smallest character is ironically the bravest. (And anyone who’s ever had a mouse infestation knows they’re not timid at all — mice are stupid brave for their size, relying on speed more than smarts!) This technique definitely lends the feel of ‘fable’ to this story, with thanks to Aesop and The Lion and the Mouse.

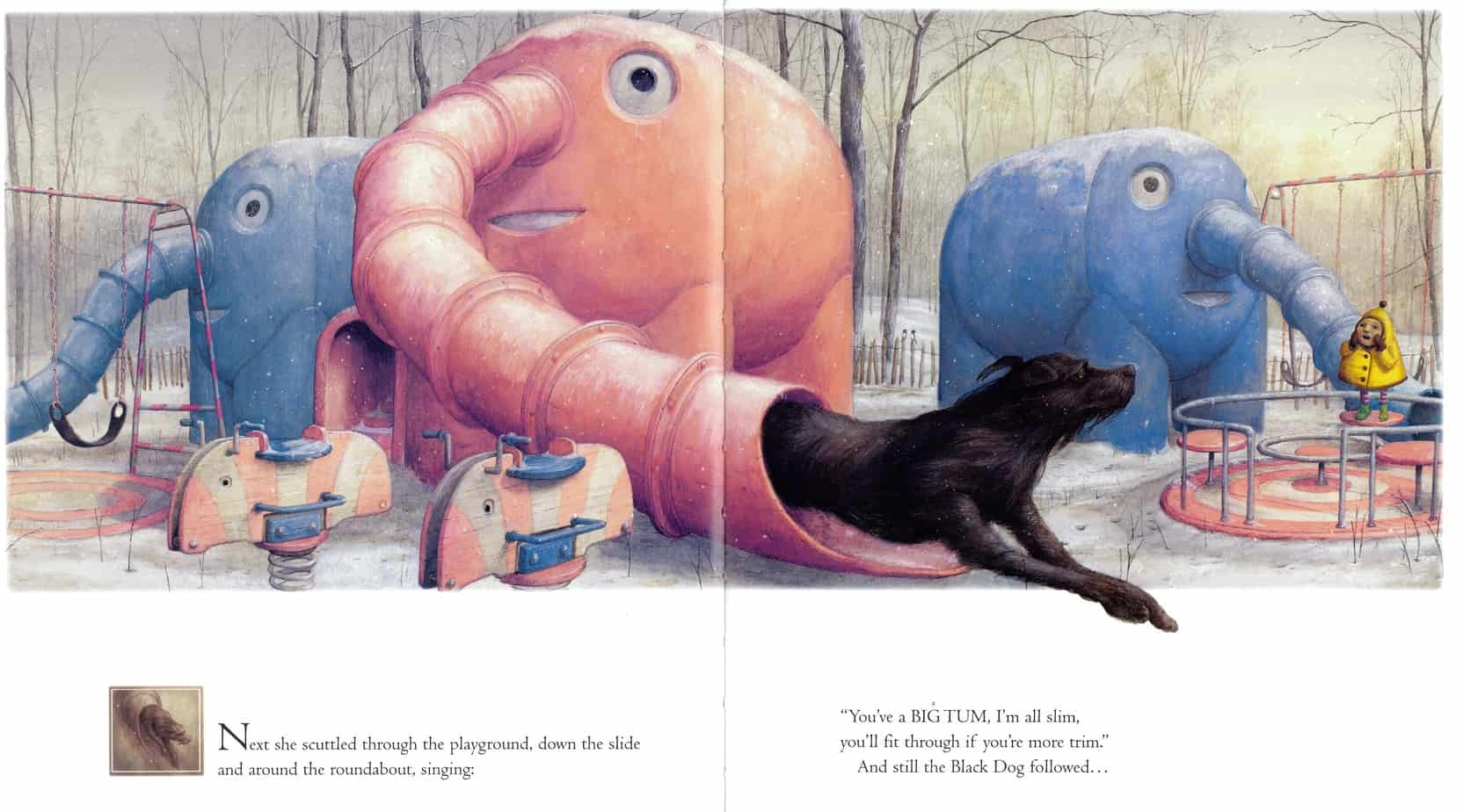

By going out into the world and practising exposure therapy the small child in this story shrinks the black dog down to size. Again, a metaphor for mental illness: mental illness is always a part of you, but it can be reduced to a manageable size.

A MINIATURE WORLD

The presence of a massive dog temporarily turns this family into miniatures, of the type you’ve seen in The Borrowers and Stuart Little.

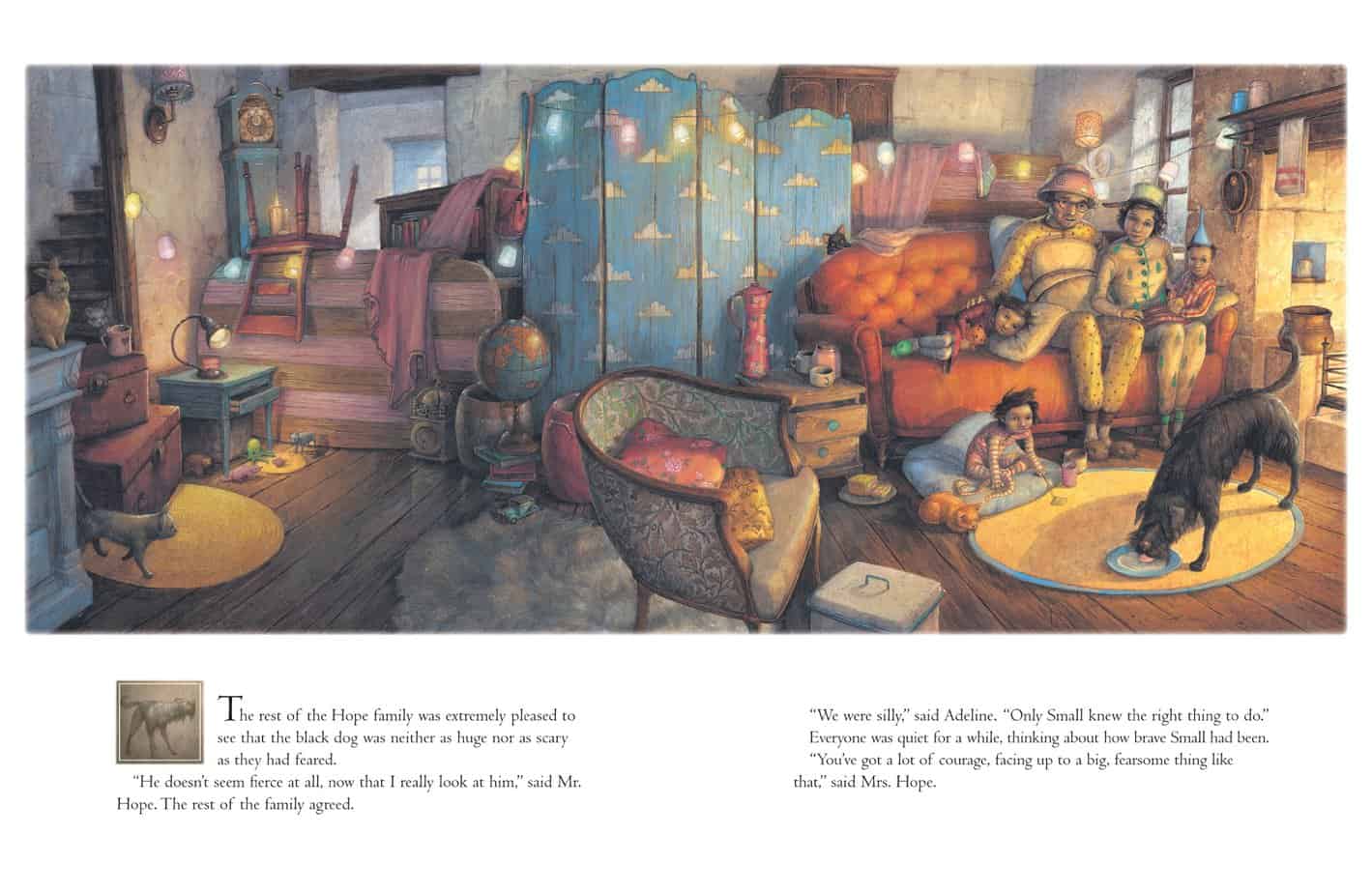

All three reasons are at play in Blackdog: We see the warm interior/foggy, cold exterior all at once; we see each member of the family react differently to the same event; we can easily imagine how scared we would be at this tyrannical creature outside our house.

JUXTAPOSITION OF SETTING

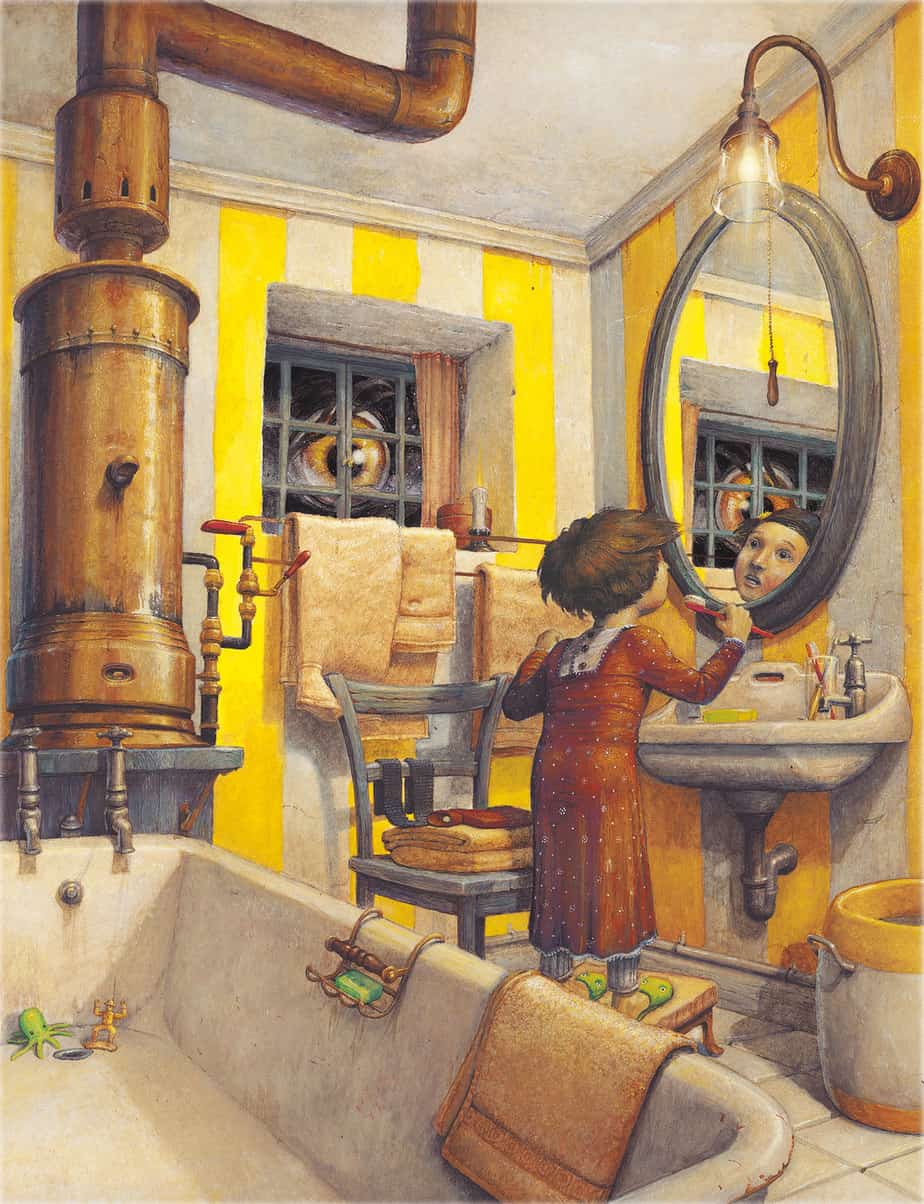

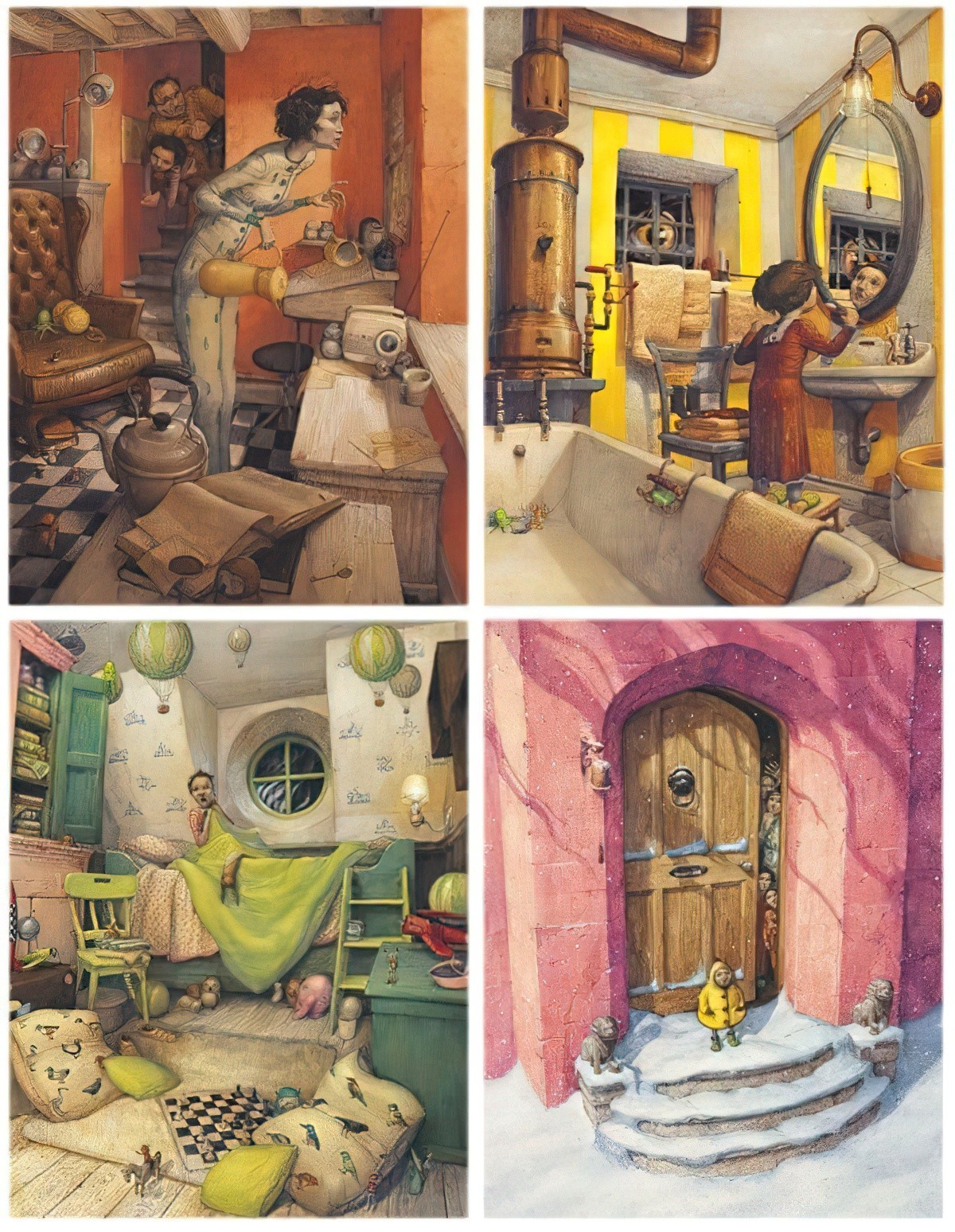

The snowy, ethereal setting of Blackdog is a brilliant choice, and is in stark contrast to the warm, but oddly grotesque interior:

There’s something steampunk about this house, and the scene of the bathroom and playground, with the rivets and steel, remind me very much of Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing.

Though Pinfold has his own distinctive style, the colour choice, too, is very Shaun Tan, especially when you look at the accent colours. Pinfold makes use of inset thumbnails, too, and in this book we have tiny sepia drawings decorating the text. It’s tempting to skip over these thumbnails because the eye tends to linger on the full-colour spreads, but if you go back and examine them closely, these thumbnails offer the ‘alternative view’ of the story: While the full colour spreads in the first half of the story depict only the inside of the house and a little of what can be seen through the window, the thumbnails show us the massive dog outside in a long shot view of the tall, skinny house.

There’s something gothic about that house. It’s a three-storied structure with an attic which would never get approved by any local council, and must have therefore come from another era. This is the trope of the Terrifying House. But this house is both terrifying and warm.

It’s warm because it’s cosy, with the roaring fire and comfort of family. It’s cheery like a rainbow, in fact, with each room having its own dominant hue. This is more obvious when you view the various parts of this house together in a single image. Orange, yellow, green, pink…

But the accoutrements scattered around — the stone animals with their staring eyes, the cluttered chaos, the soap-holder that looks almost like a mechanical hand reaching into the dirty old bath, the red tricycle that will always scare anyone who ever watched Saw — there’s something definitely spooky here. (The stone animals also remind me of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe.) And of course your warm house is also spooky… when you can never leave. The mother looks a lot like a Marionette as she clutches the jug in the orange image above. This particular form of spookiness was utilised by Neil Gaiman in Coraline.

WEATHER SYMBOLISM

Shaun Tan’s The Lost Thing — as well as his other work — features industrial smoke and city smog, but here the outside world is shrouded in a clean, forest mist — a great choice given the accepted symbolism of fog and mist. In fiction, fog equals obfuscation and mystery. In Blackdog I think it also has connections to ‘mental fug’ and not being able to see more than a couple of metres ahead, but ploughing on anyway.

WEIRD THING I DON’T GET

What on earth is a Big Jeffy, though? I expected to be rewarded with the answer after looking closely at the pictures, and I did see much earlier in the story a child’s sketch of Jeffy on the sideboard, but in the end I resorted to the internet and learned that Big Jeffy is off Sesame Street. His inclusion in this story puzzles me. Big Jeffy is a member of Little Jerry and the Monotones, supplying bass back-up for the group. He is considered to be the fourth member of the band. Maybe the author is a particular fan of Sesame Street and will reference a muppet in every picture book? Chris Van Allsburg puts a little white dog in all of his books. (It’s not even his own dog — it was his brother-in-law’s!) I haven’t read Pinfold’s other work so I can’t tell if they also include Sesame Street characters. Also, I wouldn’t be brave enough to try those guys on copyright. It’s possible that Pinfold’s Big Jeffy has no connection to the minor Sesame Street character at all.