Beauty and the Beast is a strongly mythic tale: A girl goes on a journey and ultimately finds her true self.

PARATEXT

“The Beauty and the Beast” is a tale featuring multiple levels of misogyny and much has already been said about that. For example, Was Disney’s Beauty and the Beast Re-Tooled Because Belle Wasn’t Enough Of A Feminist? Angela Carter has rewritten the tale in a way that feminists may find cathartic. One of Carter’s re-visionings is called “The Courtship of Mr. Lyon” and can be found in Carter’s collection of feminist fairy tales retold: The Bloody Chamber.

WHO FIRST WROTE BEAUTY AND THE BEAST?

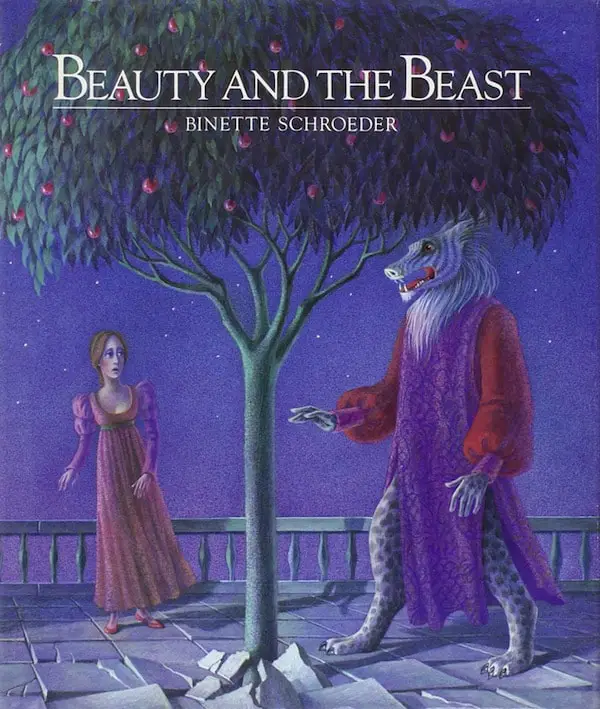

In a picture book version, intelligently illustrated by German artist Binette Schroeder in the mid 1980s, the coincidentally similarly named Anne Carter retells a tale which — I was surprised to learn — dates only so far back as the mid 1700s. This is a ‘literary fairy tale’, meaning that unlike a ‘true’ fairy tale, it did not originate from any oral tradition. It was written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740 in La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins (The Young American and Marine Tales).

The story was then bowdlerised (rewritten for children) in 1756 by a French governess who had the most erudite sounding name. It almost sounds fictional in its own right: Mme Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont.

BEAUTY AND PSYCHE

Anne Carter explains in the afterword of the Carter/Schroeder version that “Beauty and the Beast” is similar to a Greek myth about Cupid and Psyche called “The Golden Ass”. This myth dates from the second century C.E. Both stories feature:

- the palace

- nasty sisters

- the return home

The main differences:

- In the Greek myth the monster turns out to be merely invisible

- Psyche’s journey is towards intellectual/spiritual love; Beauty’s is a journey towards understanding the difference between the superficial and the real.

The main differences between the original literary tale and many modern retellings is that the original author:

- Wrote the tale for adults, not children

- Emphasised that what makes for a good partnership is respect, understanding and the ability to see past your partner’s superficial charm and into their deeper soul. Modern retellings tend to sensationalise the romance.

Perhaps surprising to a modern audience, Villeneuve’s novel doesn’t force the character of Beauty into anything. When we think of women in antiquity, we tend to think of them owned by men as chattels, and this is certainly true in some eras and some parts of the world, but the original “Beauty and the Beast” reflects the 1700s emphasis on individual rights and freedoms. The story is suggesting to its audience that even women might be afforded this right. Subsequent retellings lost this early feminist message. 1800s and 1900s retellings took Beauty’s agency away from her.

The ideas of Sigmund Freud had an impact on how “Beauty and the Beast” was retold. These are the retellings which go into themes of self-awareness and psychological development, in line with what Freud had to say about adolescent development.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “BEAUTY AND THE BEAST”

(the Carter/Schroeder version)

SHORTCOMING

With a modern reading, Beauty is indeed a flawed character. She is far too willing to please. But to a contemporary audience, Beauty was perfection itself. A model of feminine virtue, sacrificing herself to the needs of the men around her and acquiescing to her older sisters in the family hierarchy.

It’s possible that Beauty’s mother died in childbirth. I think that because she is the youngest in a large family and because women often died in childbirth in the 1700s. Perhaps Beauty’s ‘ghost’ or backstory, is that she feels guilt for bringing this misfortune upon the family, and why she feels she needs to be her father’s stand-in female companion in his old age.

DESIRE

Beauty wants to stay with her father and be his loyal companion.

OPPONENT

Beauty’s opponents are her older sisters.

Below, we see how psychologically separate the sisters are from the heroine. There are not one but two frames (doorways) between them; the sisters are from another world entirely.

The Beast appears to be an opponent but we find out he is a false-enemy ally. (Or he’s meant to be. I code him as a coercively controlling menace.)

PLAN

When Father returns with the news that one of his daughters must marry a terrifying Beast, Beauty offers herself as sacrifice, feeling that the rose incident, too, is her fault.

It’s worth remembering that Christianity in the 1700s looked a bit more like modern-day fundamentalist Islam in the respect that the devout really, truly believed that if they lived their lives according to the word of God, they would find themselves in a Heavenly paradise. When Beauty sacrifices herself to the Beast it is clear that she believes she is going there to die. But she also believes she will end up in celestial Heaven due to having been good all her life.

The Hans Christian Andersen tales are based on the same belief. That’s why the ending of “The Little Match Girl“, in which the eponymous main character dies from hypothermia (I guess) and goes to meet her grandmother in Heaven, was written to be a ‘happy ending’, and the evolution of Christian belief is why modern young readers usually fail to find it so.

BIG STRUGGLE

The Battle is a Christian-like test. The Beast (in god-like fashion) is testing Beauty when he allows her to go home to visit her natal family. Will she come back or not?

It is the Beast who goes to the edge of death rather than the beautiful and noble Beauty.

ANAGNORISIS

As Anne Carter says in the afterword: ‘for Beauty the challenge is to move from the superficial to the real, to see through the loathsome outward appearance to the goodness within. Only then, when Beauty knows and loves the virtue of her Beast, can the transformation take place.

NEW SITUATION

Beauty and the prince were married in great state and lived together throughout the length of their lives in the most perfect and deserved happiness.

RESONANCE

Why is this fairy tale so resonant? No one seems to know why. It may have appealed to a middle class wish fulfilment fantasy in which a middle-class girl can become a member of the aristocracy, elevating her entire family. (We just need to teach her to settle for someone she’s not personally attracted to, I guess.)

Today you can find this story adapted as plays, operas, film, picture books and in works of fine art. Disney adapted the tale for film in 1991. Contemporary re-visionings tend to be more feminist. Sometimes the genre of science fiction is chosen to tell a more feminist Beauty and the Beast tale e.g. “Beauty” by Tanith Lee (1983). This is an intersectionally feminist tale which also challenges homophobia and racism.

Angela Carter wrote a famous feminist re-visioning of The Beauty and the Beast in “The Tiger’s Bride” (1979). A man loses his daughter and everything else he owns in a card game. The beautiful daughter is also the narrator. She is taken to the Beast’s run-down palazzo in Northern Italy where it is, symbolically, winter. Horses live in the ruined dining room and the Beast sleeps in the den. In this story, it’s not the beast who undergoes a transformation but the virgin daughter. She takes off her clothes and even her skin and turns into a tiger.

Some modern revisionings convey the message that fear comes from resisting knowledge and difference. This is a tale which is especially prone to reinterpretation, according to the politics of the day.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

“Beauty and the Beast” continues to be popular and a wide variety of re-visionings are available from various points of view. Some allow readers to enjoy the fantasy of an S&M type romance while others critique it.

A sumptuously magical, brand new take on a tale as old as time—read the Beast’s side of the story at long last.

I am neither monster nor man—yet I am both.

I am the Beast.

The day I was cursed to this wretched existence was the day I was saved—although it did not feel so at the time.

My redemption sprung from contemptible roots; I am not proud of what I did the day her father happened upon my crumbling, isolated chateau. But if loneliness breeds desperation then I was desperate indeed, and I did what I felt I must. My shameful behaviour was unjustly rewarded.

My Isabeau. She opened my eyes, my mind and my heart; she taught me how to be human again.

And now I might lose her forever.

Belle is convinced she has the wrong name, as she lacks her sisters’ awe-inspiring beauty. So she withdraws from society, devoting her time to wood carving. Secretly, Belle longs to find the fabled Heartwood Tree. If carved by the right hands, the Heartwood will reveal the face of one’s true love.

During a fierce storm, Belle’s father stumbles upon the mysterious Heartwood — and encounters a terrifying and lonely Beast. Now Belle must carve the Heartwood to save her father, and learn to see not with the eyes of her mind, but with the eyes of her heart.

There is a pale, penetrating loneliness etched into the walls of this forgotten place. A kind of loneliness made living… is this what it feels like to be a ghost, alone in some kind of half world?

Taking shelter from a storm, Rose accidentally strays into a deserted fairy realm, and finds herself trapped there with only a mysterious talking beast for company. Although initially reluctant to befriend her strange companion, Rose quickly finds herself growing closer to him. She names him Thorn, and as the castle blossoms into a place of beauty, so too does their friendship. But something else lurks within the walls, a dark force that will stop at nothing to be free once more…

If Rose is to survive and lift the curse placed upon the castle, she will have to face her fears and conquer the nightmares that have haunted her since childhood, as well as confront the terrifying creature that stalks the shadows in the night.

Once upon a time, a girl from our world found a gate to the Faerie realm…

All Isobel wants is a quiet place to read, but apparently that’s too much to ask. She only needs to make it through one last summer with her broken family before she can leave for university and get on with her life. At least she has her books and the solitude of the woods.

But there are wolves in these woods.

Caught out in the forest after dark, Isobel is pursued by a disturbingly intelligent pack of wolves. When the grizzly bear who rescues her turns out to be a cursed fae prince, she realizes her life isn’t the only thing in danger. She could lose her heart.

Trapped by the wolves at the prince’s home in Faerie, Isobel tries to unravel the mystery behind the surly prince’s scars. Because time is running out for the castle’s inhabitants, and if Isobel can’t find a way to break the spell and save the prince from the Unseelie Queen, she may lose everything she’s come to love.

When Maren runs away from the threat of a forced marriage, the last place she expects to end up is the Malvagarian Palace, home to the enchanted gardens, a cursed prince, and a magical rose that traps her there. Crown Prince Briar isn’t pleased to be stuck with a troublesome guest, especially one as mischievous and curious as Maren. She, on the other hand, is determined to escape, but instead finds herself inconveniently falling in love with him. Despite her lack of beauty, feelings steadily blossom between her and the prince.

Their budding romance is soon threatened when sinister magic begins to eclipse the enchanted gardens, a darkness which quickly spreads not only to the kingdom, but to the king himself. In order to stop it, Briar and Maren will both be forced to make a heart-wrenching sacrifice, only to realize that the gardens’ requirements may prove too high a price.

“How? How do I make her fall in love with someone I fear and hate?”

It’s been ten years…

Since she’s seen winter.

Seen her best friend.

Seen her own hand.

When the fairy transformed the prince into a beast, she made all his servants invisible. Claudette has spent ten years without seeing a soul, cleaning the same rooms day after day, for nothing ever changes.

Candles replenish.

Flowers ever bloom.

Escape, even through death, impossible.

Until now.

For someone has found the castle. Only problem is, Beast no longer cares. It is up to Claudette to bring about the epic love story… without losing her own heart in the process.

“Beauty and the Beast” meets Pride and Prejudice in this beautiful fairy tale behind the fairy tale.

Exogamy is the word we use to describe the practice of marrying daughters out. This still happens in some cultures today. Daughters are expected to adapt to a completely new family, and sometimes these new families speak an entirely different language.

My own revisioning of Beauty and the Beast is called Winter Rose.

Even going by the most generous estimates, Mrs. Potts, the Beast’s faithful housekeeper, is clearly way too goddamn old to have given birth to her “son,” Chip. […]

A Theory That Will Change How You See Beauty And The Beast

Honest Movie Trailer for the Emma Watson adaptation

Beauty and the Beast taught me that I can be just an awful shitmongrel and still expect a beautiful woman to find and save me if I accidentally start doing the least. Am I doing this right

Studio Glibly

Stockholm syndrome is often mentioned in relation to Beauty and the Beast, but Pop Culture Detective makes an argument in favour of avoiding that term, because it heaps undue blame on the female victim, assuming she has been brainwashed. In fact, these characters show great resilience in the face of extreme abuse.

Also, Stockholm Syndrome is an invention of media. Before continuing to use this term, take a look at what Jess Hill had to say about it in her book See What You Made Me Do.

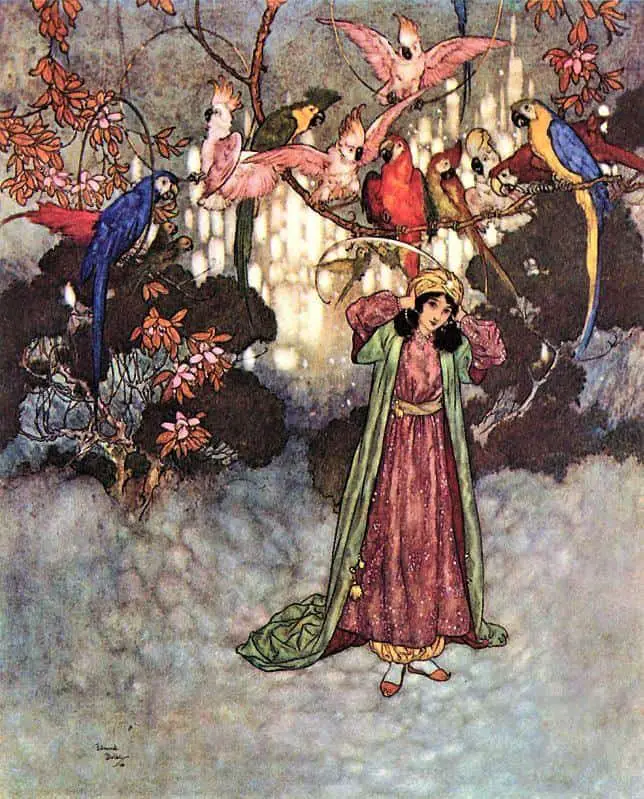

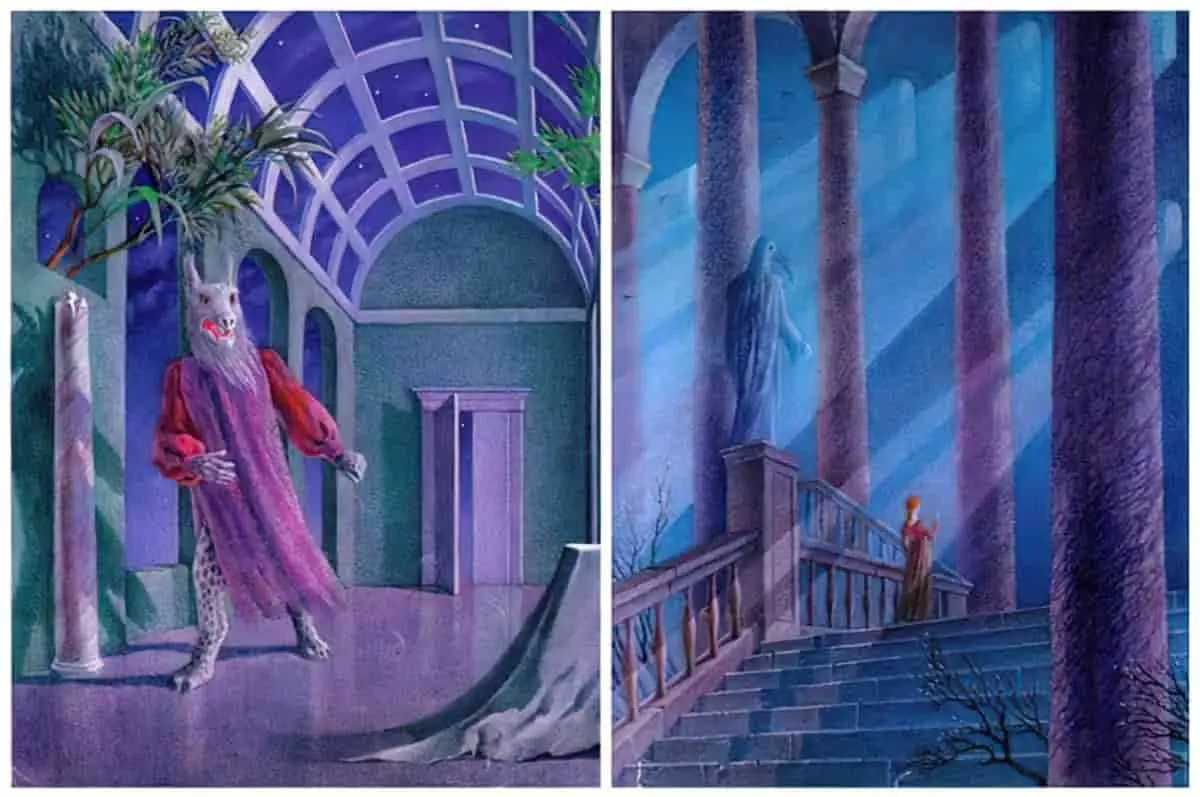

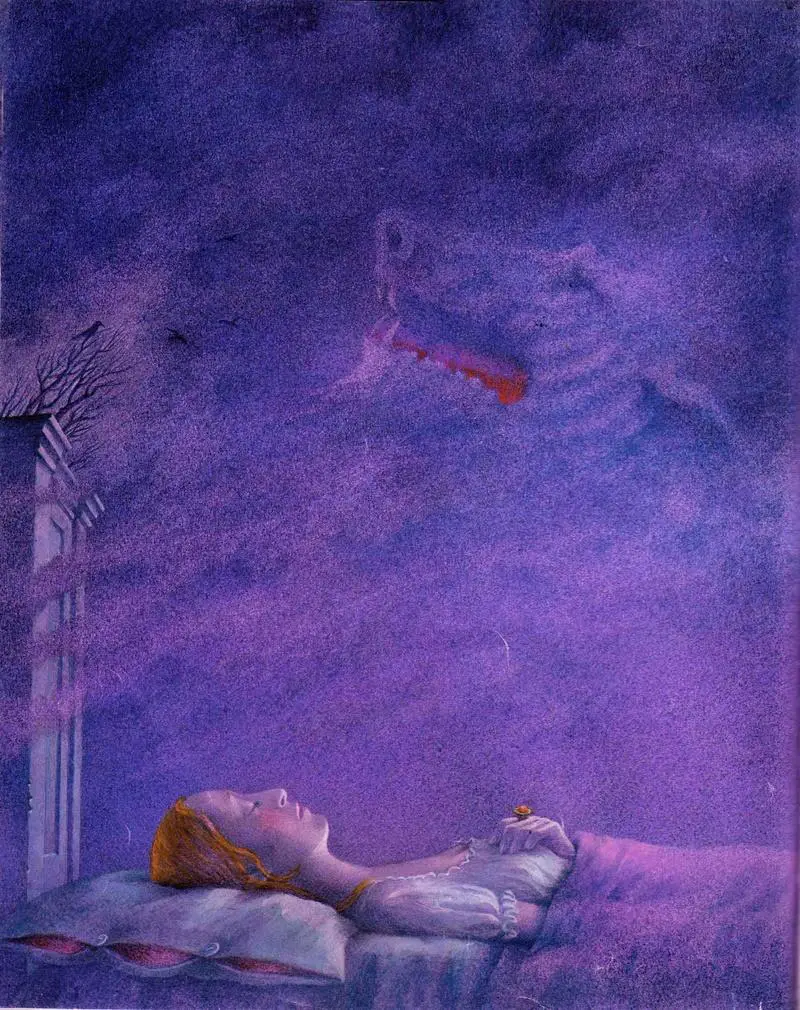

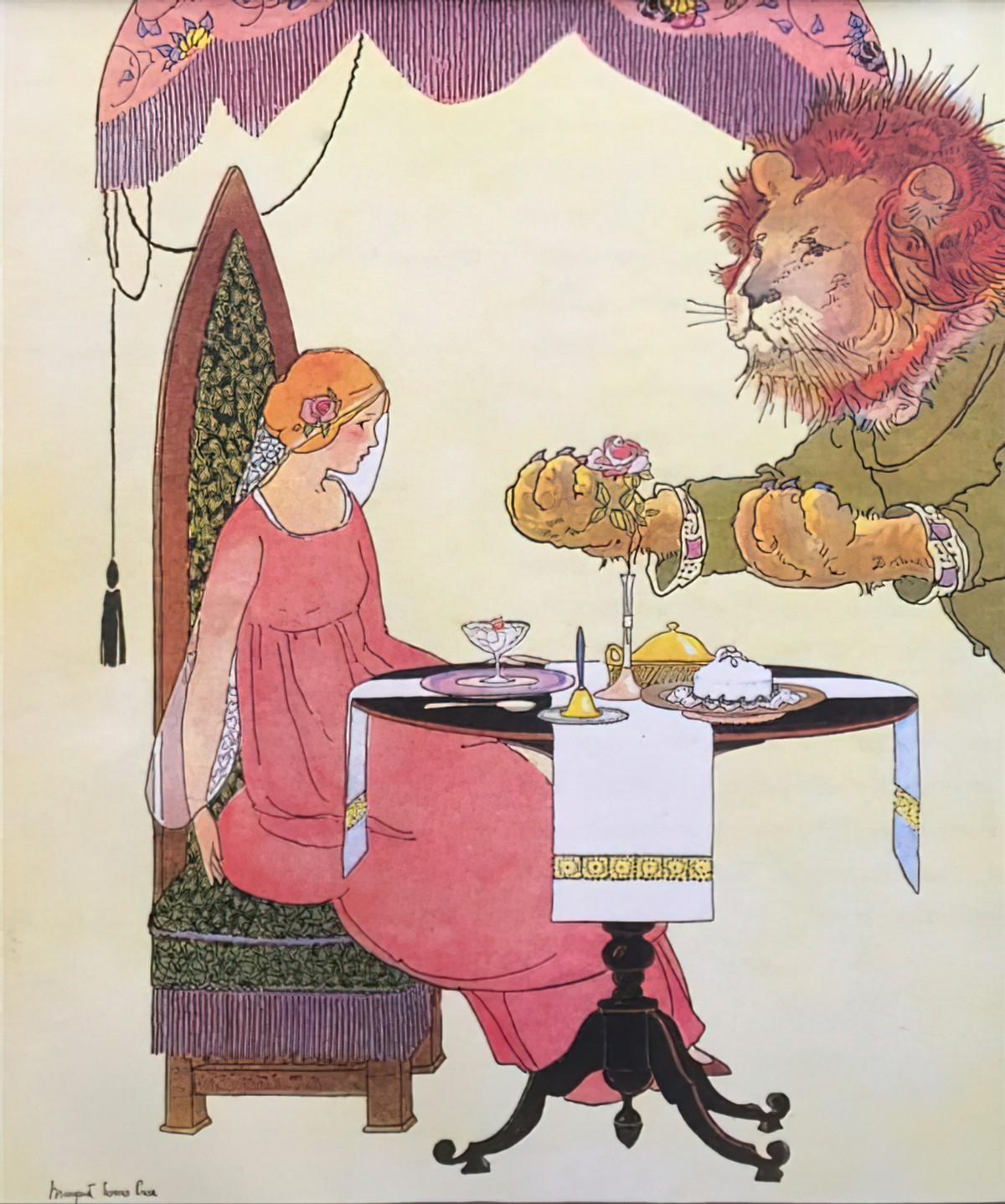

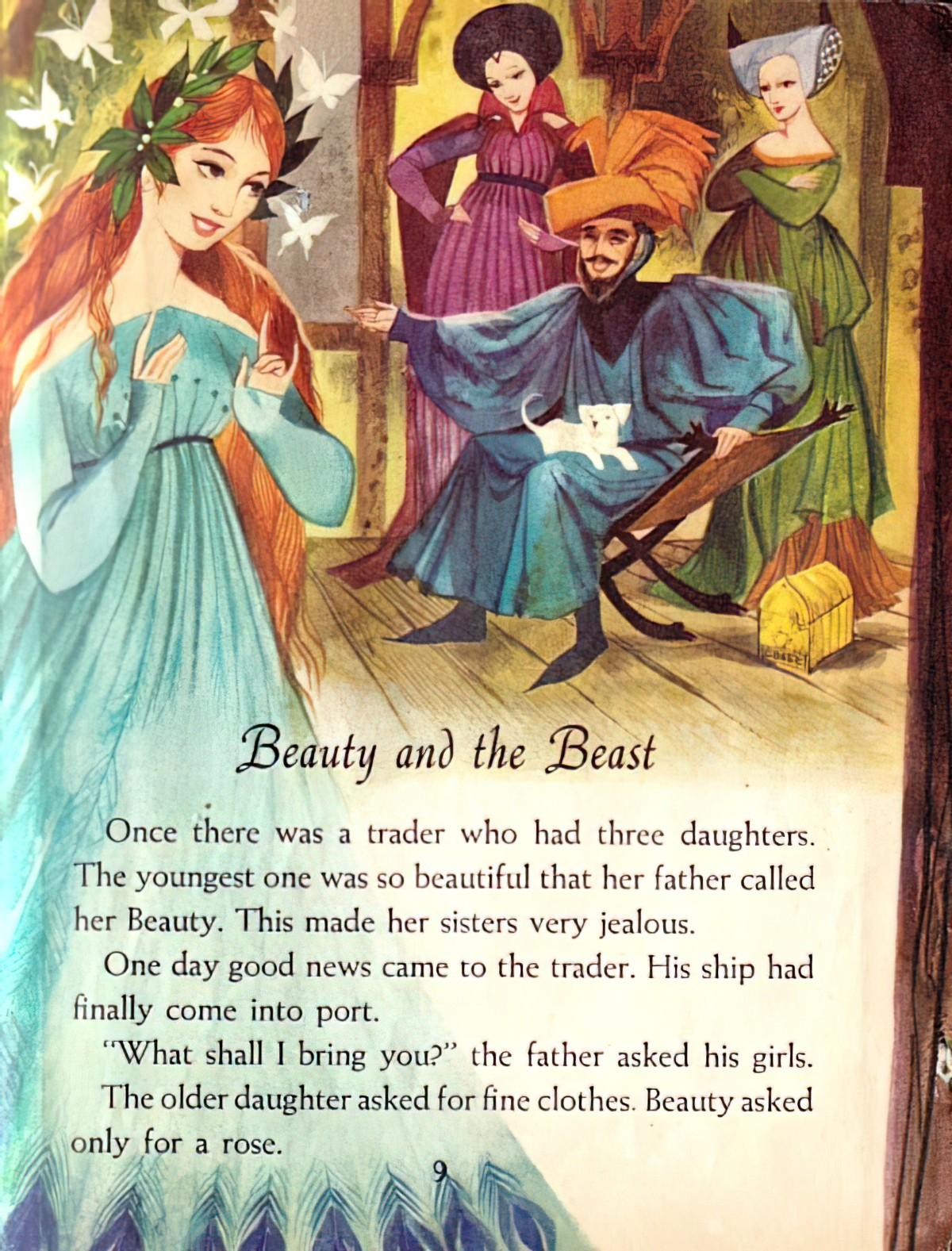

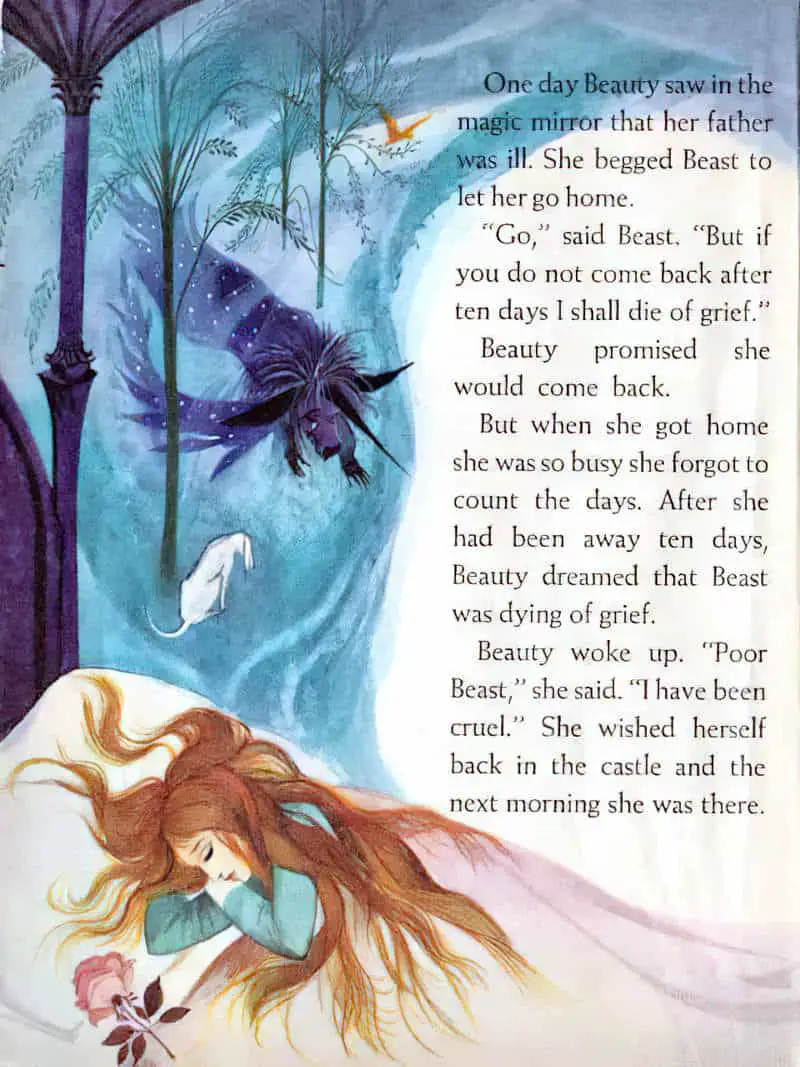

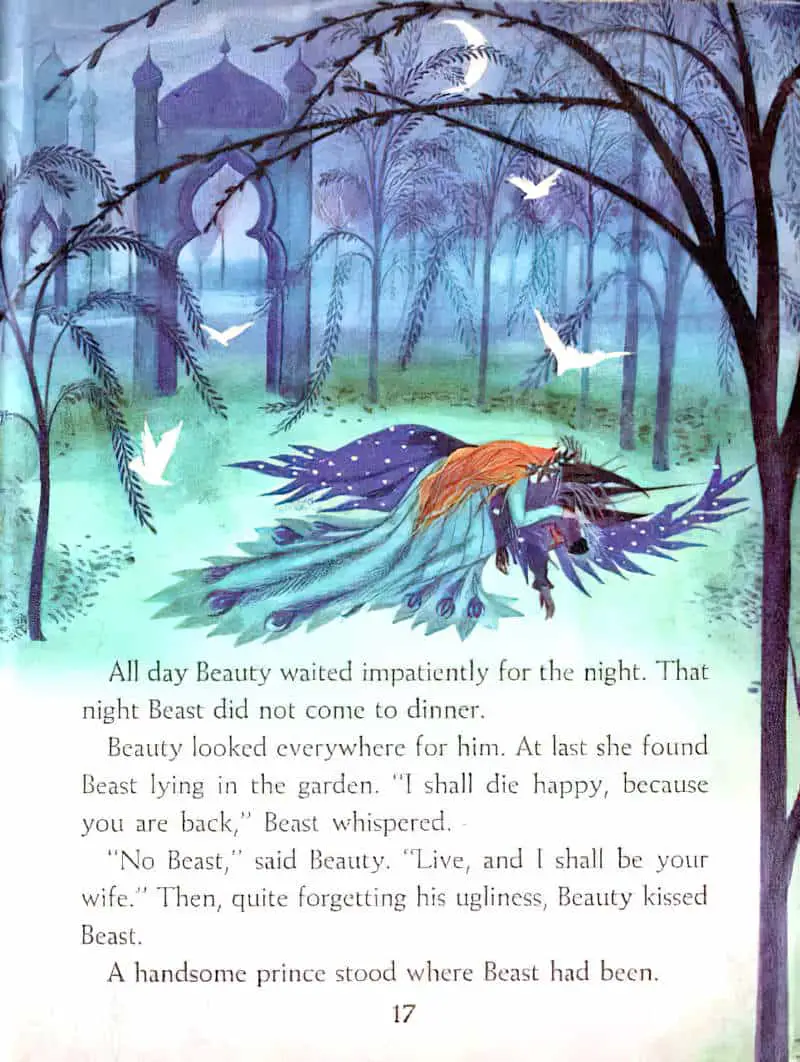

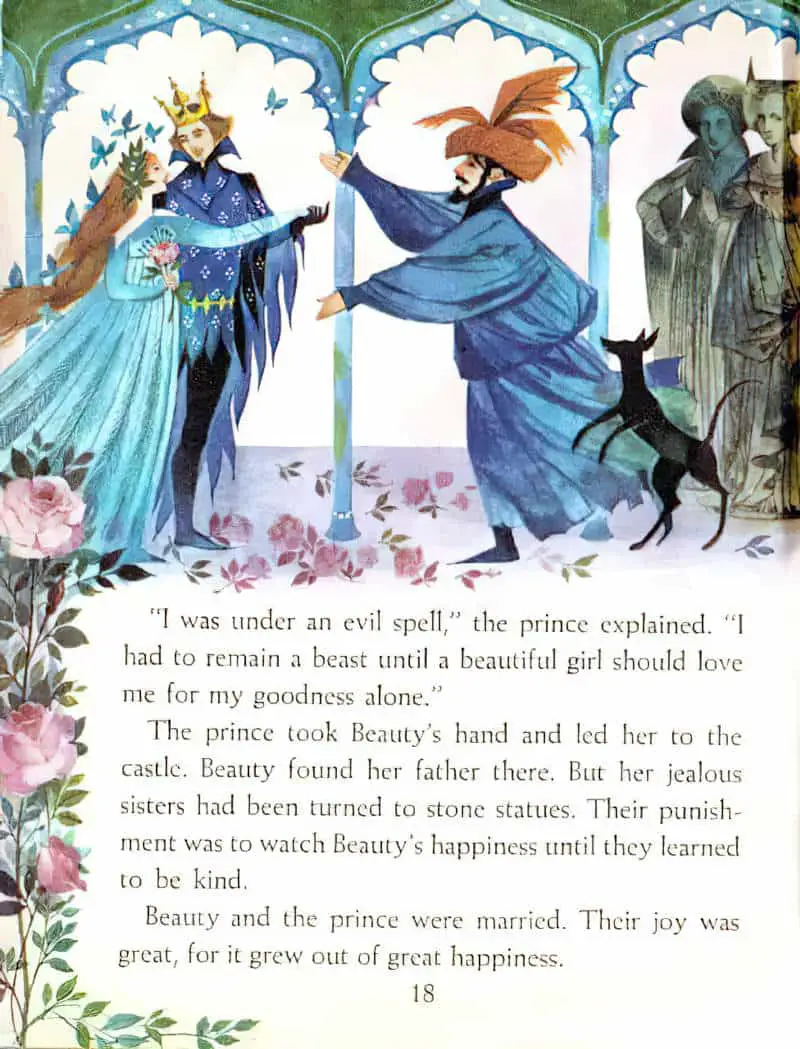

The Blue Book of Fairy Tales illustrated by Gordon Laite (1959) Beauty and the Beast

Purples and pinks are a popular choice for illustrations of Beauty and the Beast, though certainly not the only palette. The following illustrations are by Gordon Laite for a 1959 Little Golden Book.

The composition of the opening page foregrounds Beauty, marking her as the main character. Laite has also given the father a small white dog, which is an interesting addition. (Why are there not more dogs mentioned in fairy tales?)

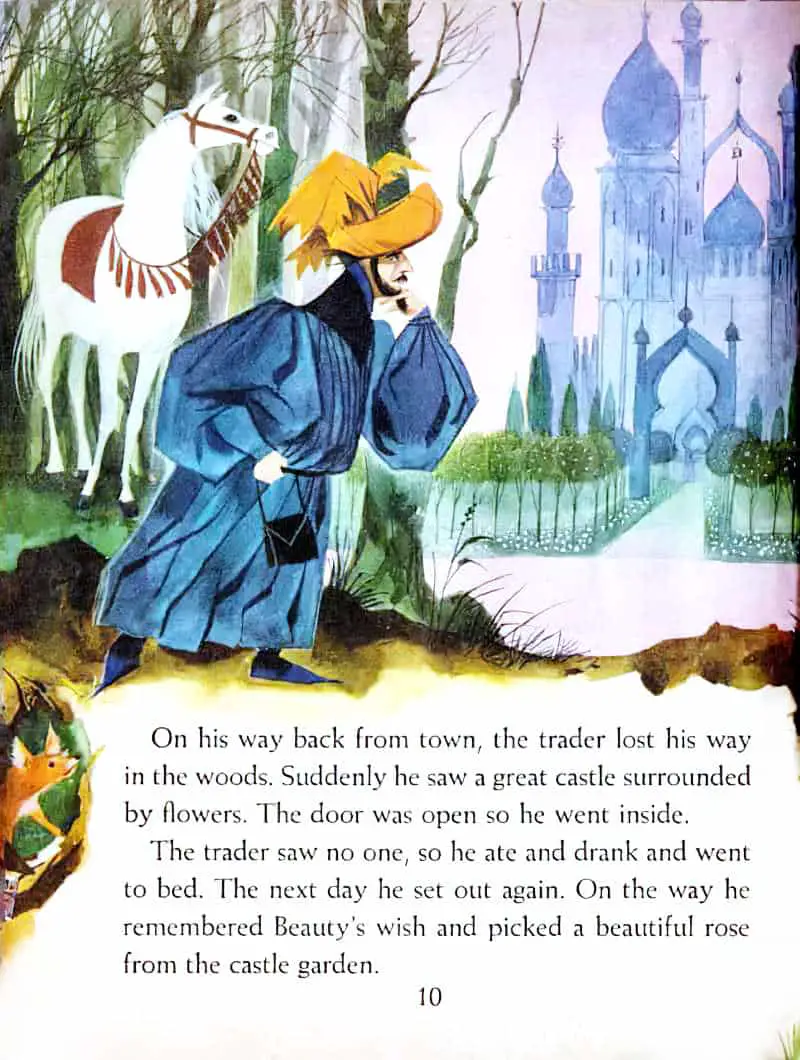

Characters who embark upon journeys frequently lose their way. In this case, I wonder what the father has been smoking. Notice the pinkish purplish aerial perspective. The father is about to enter the magical realm. In the bottom left corner, Laite adds a fox. I’m guessing Laite was a canine lover.

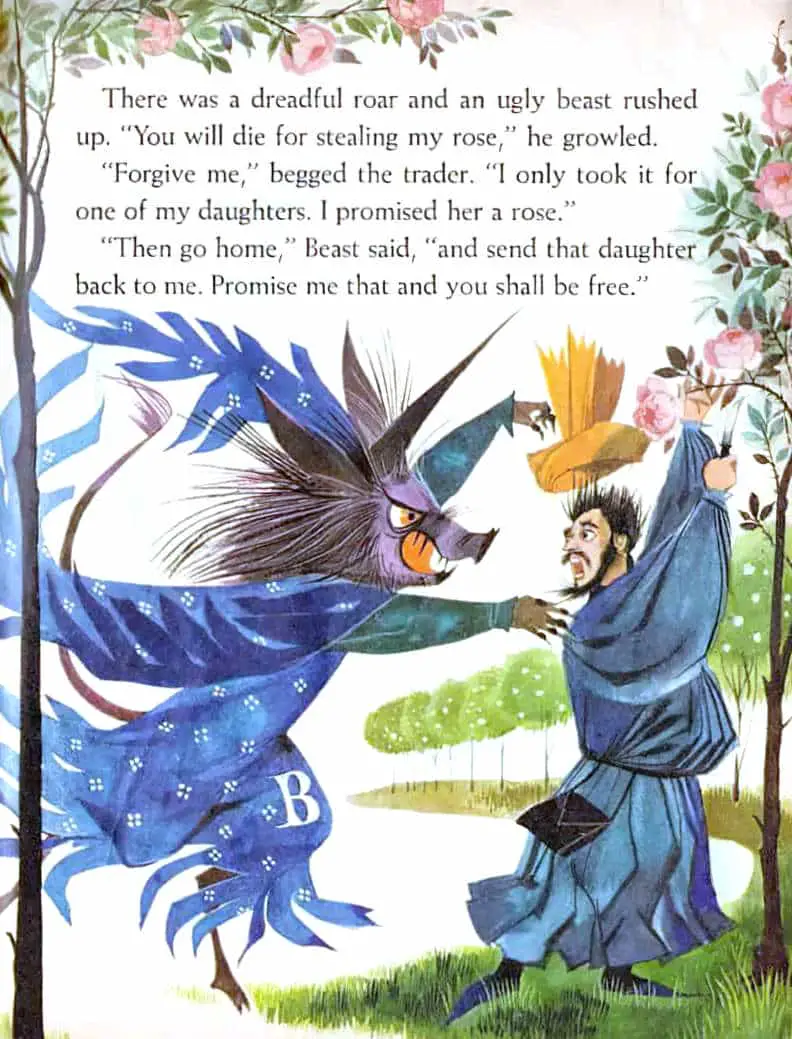

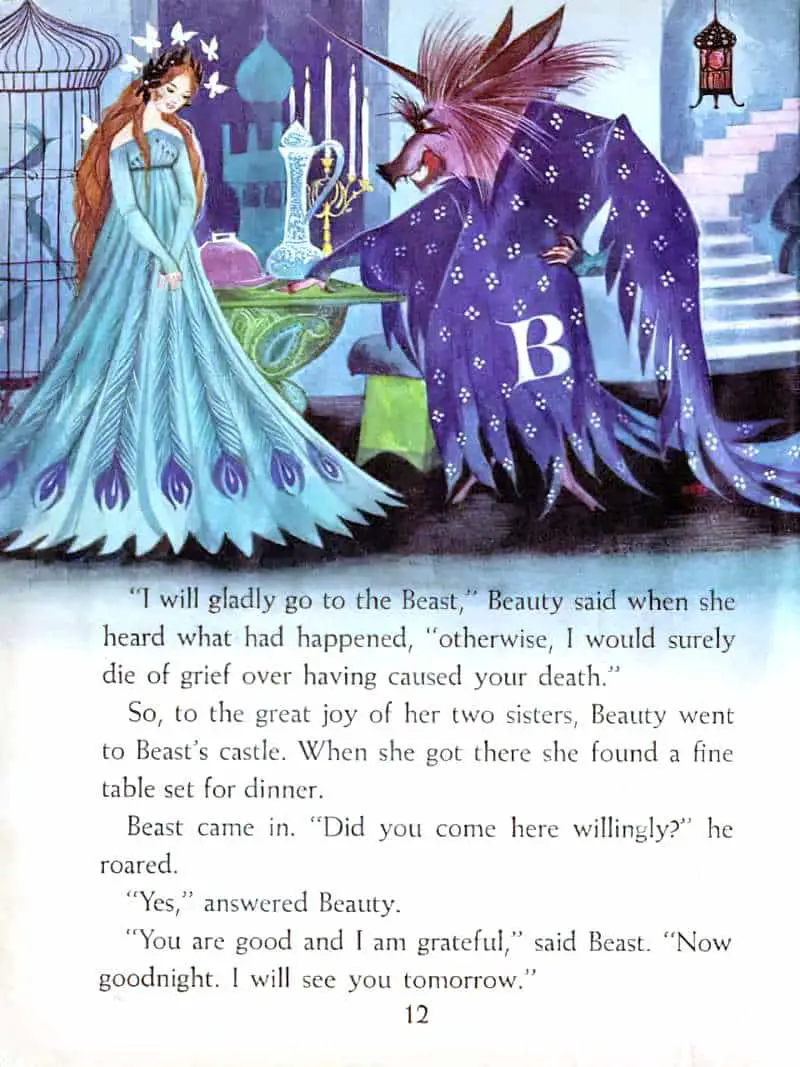

Laite depicts the beast as a wild boar with a unicorn horn. But it also has trotters, like a goat (or a devil).

What would’ve happened, I wonder, if the father promised his daughter but didn’t come through? Would the Beast have known where to find them? Couldn’t they have left town and changed their names? I mean, there was no digital footprint back then.

Laite writes the letter B on the Beast’s robe. This has the pedagogical purpose of teaching young readers a letter of the alphabet, and also reminds the Beast that he is a Beast with a capital B, I guess. Meanwhile, Beauty’s dress features peacock feathers, to underscore how beautiful she is. She also stands next to a bird cage. There’s a long tradition of women compared to birds (and also cats).

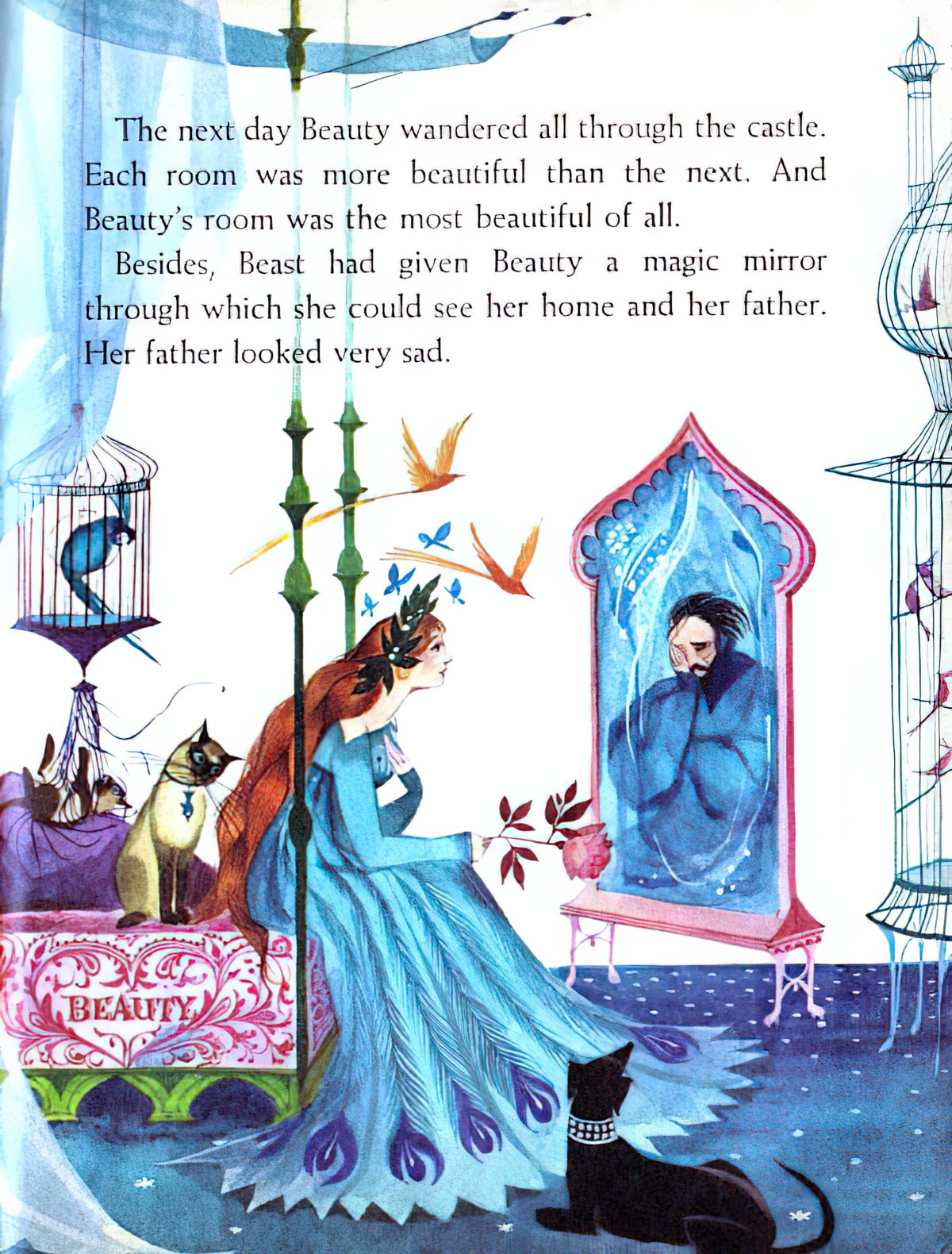

This part is a disturbing Bluebeard sequence. Beauty explores the labyrinthine castle. Unsurprisingly, Laite gives her a bird AND a Siamese cat. (Also a dog.) He’s also given us some intraiconic text: “Beauty”. This young woman isn’t allowed to forget her main role in life: To be beautiful. (Next it will be ‘To Give Birth’.)

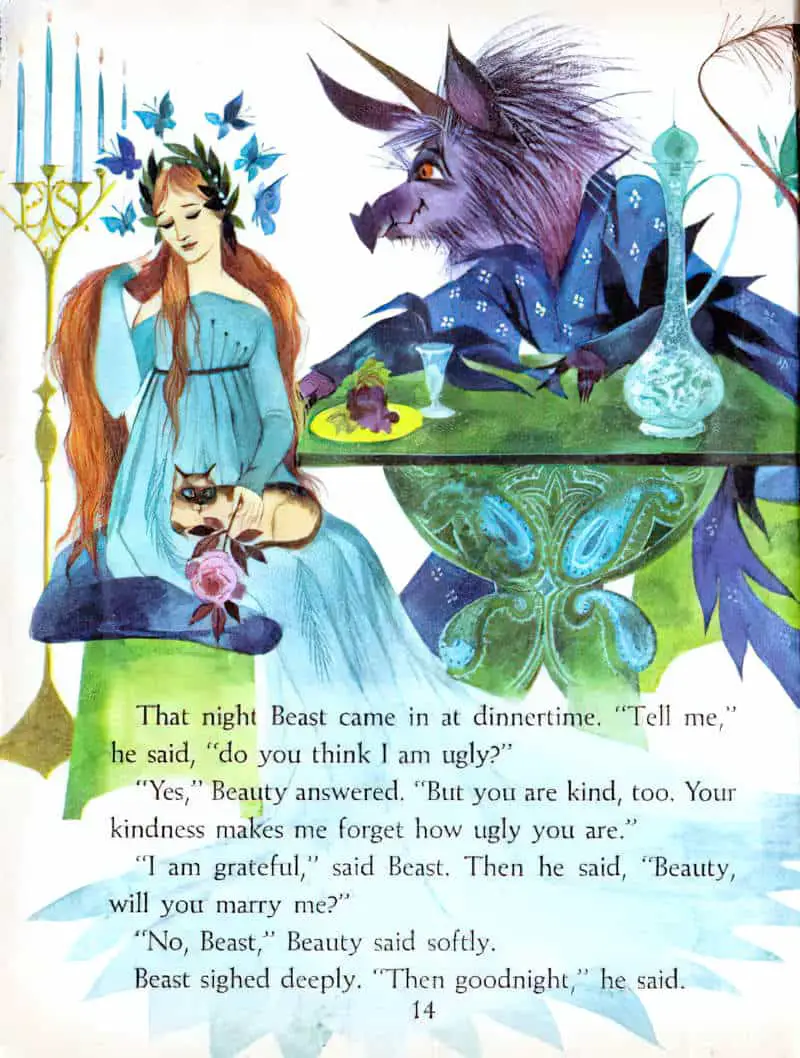

(Is he really asking her to marry him?) This sequence in the story gives the reader the false illusion that Beauty has a choice in this matter. Laite utilises some paisley patterning.

In stories from antiquity, into the present, the various types of love and attraction are telescoped into one possible outcome: Romantic love (and marriage).

That Beast has a devious look in his eye. I think Laite depicts a Beast who is feigning loneliness and, well, probably ‘blue balls’ as well, methinks.

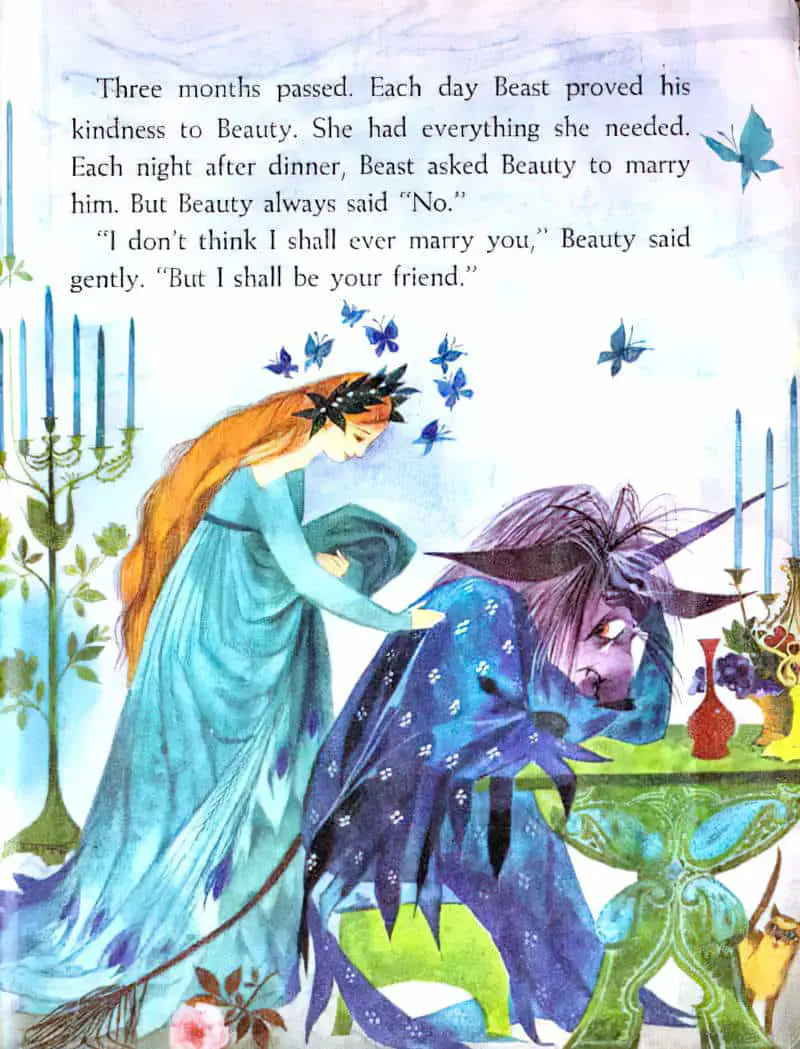

The illustration below borders the page beautifully.

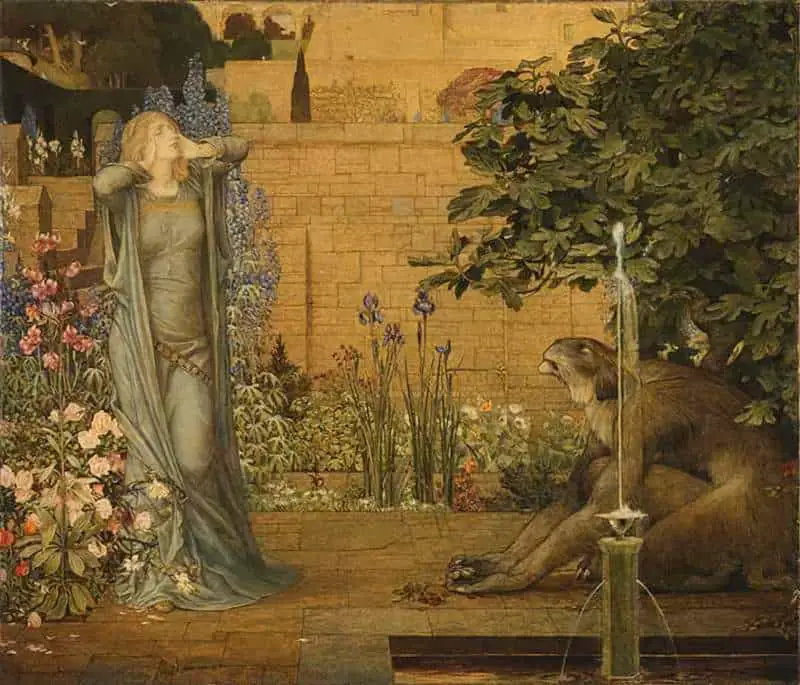

Melodramatic, much? This illustration most closely resembles the garden as depicted by Binette Schroeder.

Perhaps more modern illustrators have been influenced by Warwick Goble et al, who also depict the Beast lying pathetically in the garden. (Goble’s Beast also resembles a Boar, though from this angle he does look a bit like a donkey.)

Laite utilises archways in his composition of the reunion. The archways form a frame, dividing the prince from Beauty’s father. Beauty belongs to a new man now.

What’s with that black dog? Did the father replace the small white dog with a black one, or is the black dog his now?

Angela Barrett, my favourite illustrator of fairy tale, utilises a brownish palette for her Beauty and the Beast re-telling.