And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street was Ted Geisel’s first book. Well, he’d written an abecedary but failed to interest publishers in it. It took a while to find a publisher for this one, too, but compared to what author/illustrators are up against today, I’m guessing 20 rejections is actually pretty good.

Dr Seuss may never have moved into picture book world if Geisel had not ran into an old college classmate, who had just become juvenile editor at Vanguard Press. When I hear stories like this I wonder how many other wonderful writers and illustrators never see widespread success due to plain old lack of luck, and I feel the self-publishing movement is therefore a great thing.

RHYTHM AND PICTURES IN “AND TO THINK THAT I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET”

Legend has it that Geisel came up with this story on a ship. To ward off sea sickness he concocted a story. The rhythm is inspired by the ship’s engine. Of course, Geisel continued to write his picture books in that signature rhythm — a rhythm many writers have subsequently tried to pull off — perhaps more young rhymsters should take a cruise on a clunky old-timey steam ship??

(Why did we not see a movement of poetry inspired by a dial-up modem in the late 90s? Haha.)

Perry Nodelman has this to say about the rhythm and ‘curious reversal’ of Mulberry Street:

The regular rhythms […] have the strong beats and obvious patterns we usually expect of pictures in sequence; and as usual in a Dr. Seuss book, the action-filled cartooning does much to break up the regular rhythms inevitable in a pictorial sequence. But as the boy, Marco, adds details to his complex story of what he saw on Mulberry Street, the pictures become more and more complex, more and more filled with detail — but always in terms of the same basic compositional patterns: the elephant is always in the same place on each spread, and so on. So the pictures both build in intensity and maintain their narrative connection with each other, as the words in a story usually do; in each picture we look for new information to add to old, rather than having to start from scratch about what we are seeing each time, as usually happens in picture books. At the same time, the segments of text get shorter and tend to be interrupted by more periods. The result is a curious reversal, in which the text adds the strong regular beat and the pictures provide a surprisingly inter-connected narrative intensity. Indeed, many fine picture books create the rich tensions of successful narrative in pictures that strain toward the narrative qualities of text and in texts that strain toward the narrative qualities of pictures: they have repetitive rhythmic texts, and pictures with accelerating intensity.

Words About Pictures, Perry Nodelman

The details in this story plant it firmly in the First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature.

Modern stories of the imagination don’t tend to include Rajahs riding elephants and ‘Chinamen’. This is why parents and book buyers should look a bit further for book gifts than literature from our own childhood. If you’re looking for a carnivalesque book for a gift, with great rhyme, you’ll find many examples on this website. (I recommend Hairy Maclary by Lynley Dodd.)

If you’re looking for something classic, as in old, the following were published at the same time:

- Make Way For Ducklings by Robert McCloskey

- Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans (problematic in different ways e.g. the gypsies)

- Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf (groundbreaking with its cinematic perspective)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “AND TO THINK THAT I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET”

A boy imagines a series of incredible sights on his way home from school so that he will have an interesting report to give his father.

PARATEXT

It’s interesting to see that the front cover has been published in varying shades of blue:

SHORTCOMING

Marco is fanciful. He’ll lie about something in order to make his life more interesting. Some may see this as a shortcoming; the shortcomings of picturebook characters often have very benign psychological shortcomings — a big imagination is more properly considered a strength.

DESIRE

He wants to impress his father.

Throughout his work, Geisel seemed more at home writing about the typically male experience and it’s true here, too, with an understanding of how sons naturally want to impress their dads.

This book, of the Tall Tale type, is an historically masculine form.

OPPONENT

The father is a kind of opponent in that he has no time for Marco’s fanciful stories.

PLAN

He decides to make up a story that’s far more interesting than reality.

BIG STRUGGLE

In a cumulative, imaginative, carnivalesque story such as this, there may not be any big struggle between the child and the other characters. Instead, the ‘battle scene’ will be ‘the moment of extreme chaos’.

This is the illustration with everything in it.

ANAGNORISIS

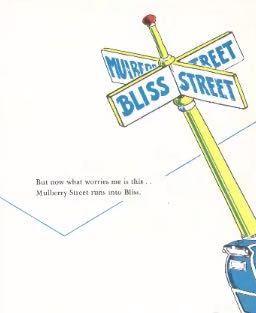

In a chaotic, carnivalesque plot, ideally there will be a ‘breather’. Here, the anagnorisis comes with the image of the crossroad.

Note all the white space — the picturebook equivalent of a musical sequence with no dialogue in film.

Humans have been fascinated by crossroads since crossroads existed. In each case there is a spiritual significance. Something about crossroads has made earlier cultures superstitious:

- Ghosts/apparitions appear at crossroads

- Crossroads mark hallowed ground

- Witches secretly meet at crossroads to conduct their nasty witchy stuff

- Zeus hung out at crossroads

- etc

None of this is going on here, exactly. In modern stories (like this) crossroads have lost their spiritual meaning but remain a psychological metaphor. Marco must make a decision very soon: Will he lie to his father or tell him the truth? In other words, crossroads in modern stories mean choice.

The anagnorisis is that Marco has the power to make his own choice.

NEW SITUATION

In order to keep his father happy, the boy makes the decision to keep these fanciful imaginings to himself. He tells his father what he really saw.

EXTRAPOLATION

Extrapolating somewhat, this boy seems embarrassed about his imagination running away on him, so I expect he’ll hit adolescence soon and leave his imagination behind.

RESONANCE

By consensus, Dr. Seuss — born Theodor Seuss Geisel in Springfield, Mass., in 1904 — was the greatest American picture-book artist of the modern era. Every one of the 44 children’s books he wrote remains in print (”Horton Hatches the Egg,” first published in 1940, has been reprinted more than 80 times), and to paraphrase the man himself, the number of readers is on beyond millions. Counting classics like ”The Cat in the Hat” and less well-known titles (including those published under the pseudonyms Theo. LeSieg and Rosetta Stone), total trade sales passed the 200 million mark a decade ago. Like the Grinch’s heart on Christmas morning, Dr. Seuss’s place in the cultural landscape has grown at least three sizes since his death. In addition to a handful of posthumous publications, there is Seuss Landing, a theme park within Universal Islands of Adventure in Orlando, Fla., ”Seussical,” a new Broadway musical and Universal’s live-action Grinch movie, which recently opened. (Three new movie tie-ins are available from Random House; two have already landed on The Times’s children’s best-seller list.)

Sense and Nonsense, NYT, A. O. Scott

Even within the author’s own lifetime, it was acknowledged (by the author himself, when he was older) that imagery in his earlier work was racist.

We are also now just starting to talk about how the characters in his work are very white. Finally, come March 2021:

Dr. Seuss’ whimsical stories have educated and entertained generations of children. But many of his books are now being pulled for depicting racially insensitive images.

6 Dr. Seuss Books With Racist Imagery Will No Longer Be Published

There is still a place for discussing the racism and whiteness of this book, but I’d keep that for older readers. (The implied reader is the preschool set.)

STORY SPECS OF “AND TO THINK THAT I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET”

Between 30 and 40 pages long, depending on the edition

And then it came out in yellow, and the recognisable red and white spine, along with the rest of the Dr Seuss collection.

COMPARE “AND TO THINK I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET” WITH

Marco appears again, ten years later, in McElligot’s Pool.