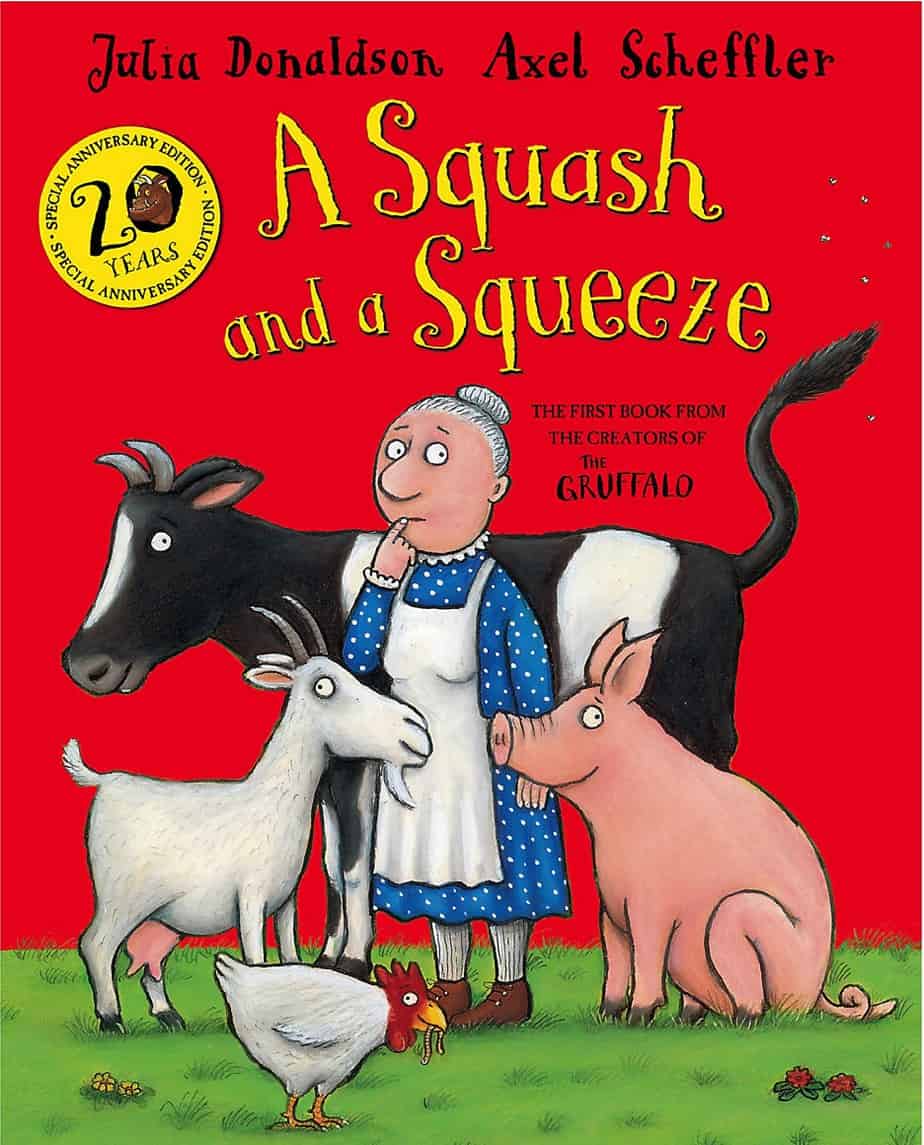

A Squash and a Squeeze is a 1993 picture book written by Julia Donaldson, illustrated by Axel Sheffler. The plot is very old.

A Squash and a Squeeze was published in 1993, when Donaldson was 44. It was not expected to be a big seller. For one thing, it was in rhyme, which publishers at the time largely avoided because of difficulties with translation. “In order for a picture book to be profitable, you more or less have to glue some foreign editions on, so you can do a bigger print run,” Donaldson said.

The Guardian

Donaldson’s great gift is two-fold: weaving old folktale tropes into contemporary stories, and with beautiful, read-aloud prose. This particular story is a retelling of an old Yiddish tale and, to be honest, I wish there were more acknowledgement of this heritage in editions and reviews of A Squash and a Squeeze. Even the tentpole authors are heavily reliant upon a long tradition of storyteller and storytellers.

There are other picture book retellings of this story. Too Much Noise by Ann McGovern, with illustrations by Simms Taback (1967) has fallen into obscurity, though I picked up a copy for free when our local library was having a throw out. (This sort of proves its obscurity.)

Another example is A Big Quiet House by Heather Forest and illustrated by Susan Greenstein (1996).

You’ll find many folktale tropes here: Witches, chimeras, rats, mice, and here: a mentor archetype. Then there’s a trope most often found in fairytales and in picture books: an old woman who lives alone on a simple small plot of land in the country. This woman will probably have a close relationship with her animals (and if she doesn’t, she’ll be forced to, here!) The older Yiddish tales are about a man who lives alone in a house, so Donaldson has inverted the gender. (At first this may look like an act of feminism, but I don’t believe Donaldson is a feminist storyteller.) In the Yiddish tale the man goes to a woman for help; now we have a woman going to a man for help. This is an inversion, not a subversion. (There’s a difference.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF A SQUASH AND A SQUEEZE

PARATEXT

There have been various editions of A Squash And A Squeeze in its 20+ year history of reprints.

Here is a slightly more ominous sky:

With the help of an old man and all of her animals, an old lady realises that her house is not as small as she thought it was.

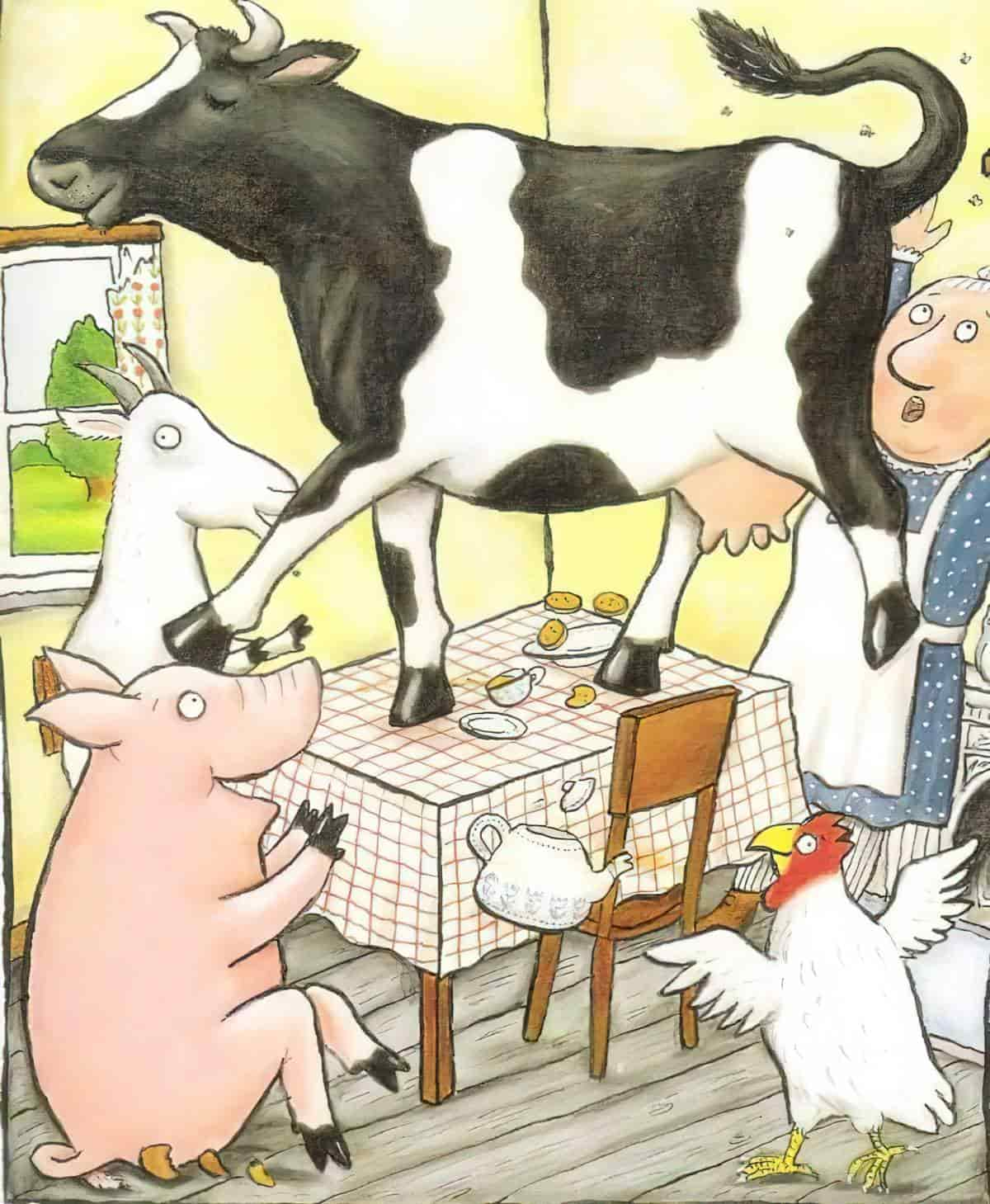

“a bit of a classic … A goat on the bed and a cow on the table tapping out a jig? My readers collapsed in heaps, and then had to have it read again. And again.”

Vivian French in The Guardian

SHORTCOMING

The old woman feels her little house is too small for her. The four walls make her feel ‘squashed and squeezed’. Donaldson brings the freshness of onomatopoeic/mimetic language to this revisioning.

DESIRE

She wants a bigger house, we guess.

OPPONENT

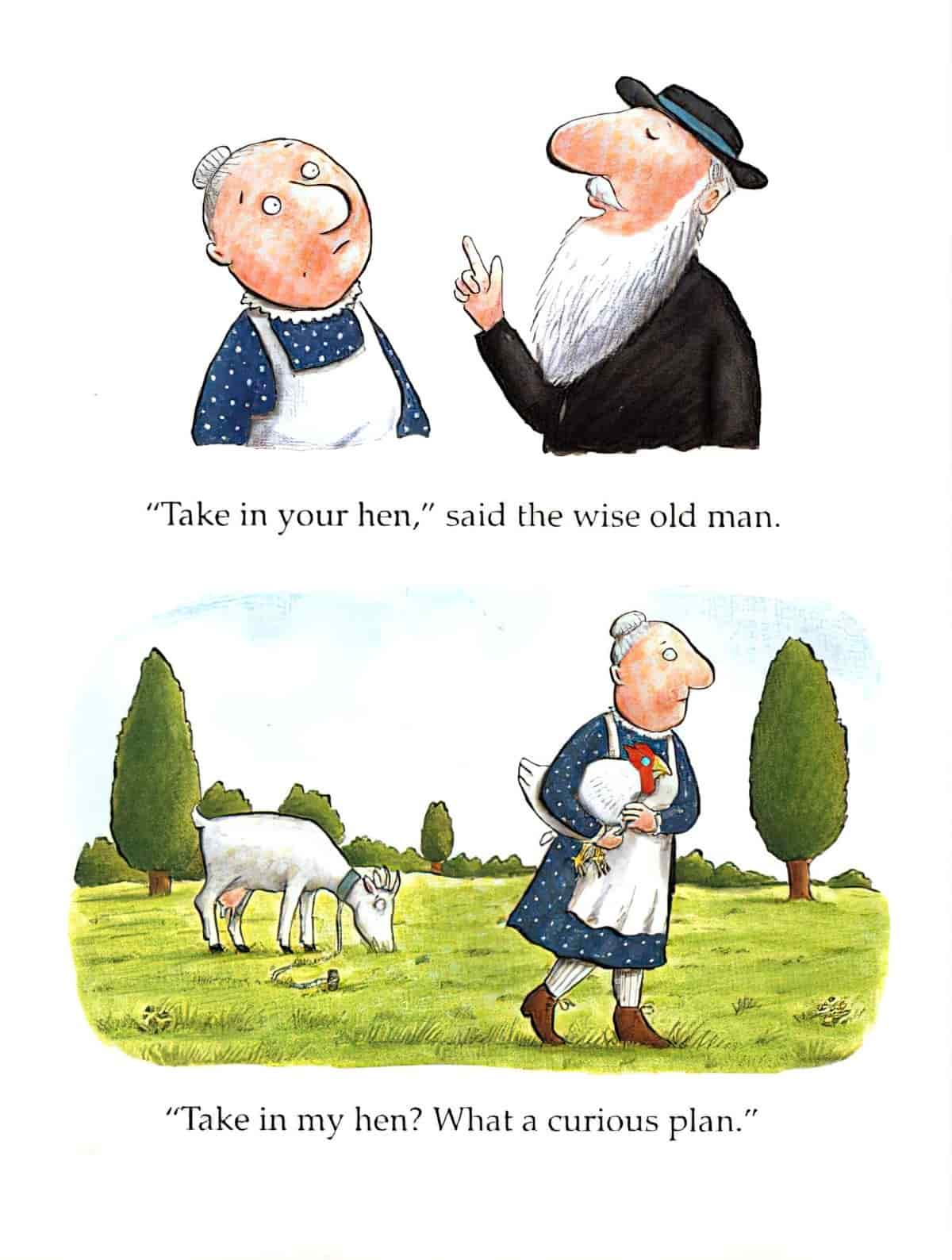

The Wise Old Man is a secret-ally opponent. He at first seems to be making her situation worse, but there’s method in his madness.

PLAN

She asks the local Wise Old Man what to do.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scenes are slap stick set pieces as the Wise Old Man tells her to bring her farm animals into the house. He starts her off on the smallest farm animals and ends with the cow.

ANAGNORISIS

Compared to having a house full of farm animals, a cottage with just her in it no longer seems so small.

Is this a messed up version of gratitude culture? Kate Manne writes in her newsletter:

[G]ratitude has a dark side, and I think we need to talk about it. How often is our gratitude, or at least the ways we express it, a way of telling others that they’re our worst-case scenario? When does gratitude read as fear and pity with a side of downward comparison? […]

[P]erhaps the creepiest of all of these practices was asking overworked, underpaid nurses to spend part of their morning meeting listing three things they were grateful for—and this during a bid to improve workplace conditions. “I’m grateful it’s not even worse,” seemed to be the thinking this little exercise was designed to solicit.

Kate Manne, “The Dark Side of Gratitude”

NEW SITUATION

The animals live happily in the yard and the old woman lives happily in her cottage, no longer feeling it’s too small.

FURTHER READING

Picture books are easy to read – Donaldson’s usually run at just 32 pages, and under 1,000 words – which can give the mistaken impression that they are easy to write. This myth has been reinforced by the publishing industry’s penchant for indulging celebrity authors, who are seen as a guarantee of press coverage and sales, though the books themselves are often ghost-written or heavily edited, and few are unqualified successes. Donaldson has repeatedly complained that picture book authors do not receive “the recognition they deserve”, lamenting at the 2019 Hay festival that “everything has to be the next big thing or else just go out of print”.

Similar charges, meanwhile, have been levelled at Donaldson, whose dominance of the picture book genre is seen by some as crowding out the market for new titles. “Some authors are a bit sniffy about her, but I think that’s just pure and simple jealousy because she’s so successful and she gets all that shelf space,” the author and illustrator Rob Biddulph told me. “But there’s a reason for it: she’s a genius.”

The Guardian

Julia Donaldson is indeed a rhyming genius, and like many geniuses, Donaldson occasionally rewrites formerly published stories, sometimes without changing the plot at all. How many of us have a copy of A Squash And A Squeeze on our shelves, but have never heard of Too Much Noise or A Big Quiet House? Perhaps this is what the ‘sniffy’ authors are talking about.