The story of Helen Palmer is — from the outside, certainly — a sad one.

Helen is ‘the woman behind the man’ in the Dr Seuss duo. It was Helen who encouraged her husband Theo to start writing picture books.

When the marriage ended and Theo embarked upon a second relationship, Helen suicided. It would be nice to think that her separation from Theo had nothing to do with it, because had been dealing with cancer for a long time. But the truth is, she left a note. So we know that had almost everything to do with the timing of it.

Helen was a much better editor than she was a writer, which I’d like to emphasise is no small skill in itself. (Roald Dahl’s editors, for example, had a MUCH bigger hand in making him look great than most people realise.)

The book A Fish Out Of Water is a story that Theo cast aside. He didn’t think it worked. Helen disagreed and made sure it was seen by the world. It’s still reasonably easy to get a hold of. I somehow ended up with two secondhand copies on my bookshelf, for instance. This is possibly a sign that it’s a picture book people decide not to keep.

If this had Dr Seuss’s name on the cover I would certainly agree that this is not him at his finest. I agree with him that it doesn’t work. Let’s take a closer look to try and find out precisely why it doesn’t work, and why Helen thought it still had merit.

The illustrations, by P.D. Eastman are as attractive as those done by Theo himself, if without the distinctive colour palette, so it must have something to do with the text or the plot. First, the plot:

STORY STRUCTURE

SHORTCOMING

A boy needs something to nurture and he is the sort of kid who does what he’s told not to do.

He needs to learn to be obedient.

DESIRE

A boy wants a goldfish. Not only that, he wants to nurture the fish.

So far so good. This is all established on the first couple of pages.

OPPONENT

This is a carnivalesque story, so the opponents are the circumstances themselves. The fish getting huge.

Again, so far, so good. It’s common and usually very successful to write a children’s book about something either very big or very small. The young reader enjoys seeing this fish getting bigger and bigger, and can probably predict that it will end up in the swimming pool, or perhaps the ocean.

PLAN

Unfortunately this is where the plot starts to unravel. The boy can’t solve this on his own — first he calls the police. This is kind of comical in itself because the police are depicted as being right on the end of the phone waiting for his call, and it is clear that they deal with the overfeeding of giant fish on a regular basis.

The problem with putting the fish into the pool is that the swimmers don’t like it, so the boy’s plan changes and he is forced to call the man who sold him the fish.

It’s never ideal to have adults step in and save the day. Not in a children’s book. Even if an adult technically saves the day, the child hero must show more initiative.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘big struggle’ in a carnivalesque book is a sequence of increasingly dire situations, and these keep going until the writer’s imagination is at a limit. Preferably, in the most successful stories of this type, the writer is able to go one or two steps further than the reader’s imagination. A great example of this is Stuck by Oliver Jeffers. Just when you think nothing more could happen, it does. This is where the surprise comes in, and carnivalesque stories in particular are all about fun and surprise.

There is no surprise here. All of us could imagine a giant fish being taken to the town swimming pool, and in fact I expected the fish to end up in the ocean.

The big struggle sequence does not surprise us enough.

ANAGNORISIS

This is where the book really fails.

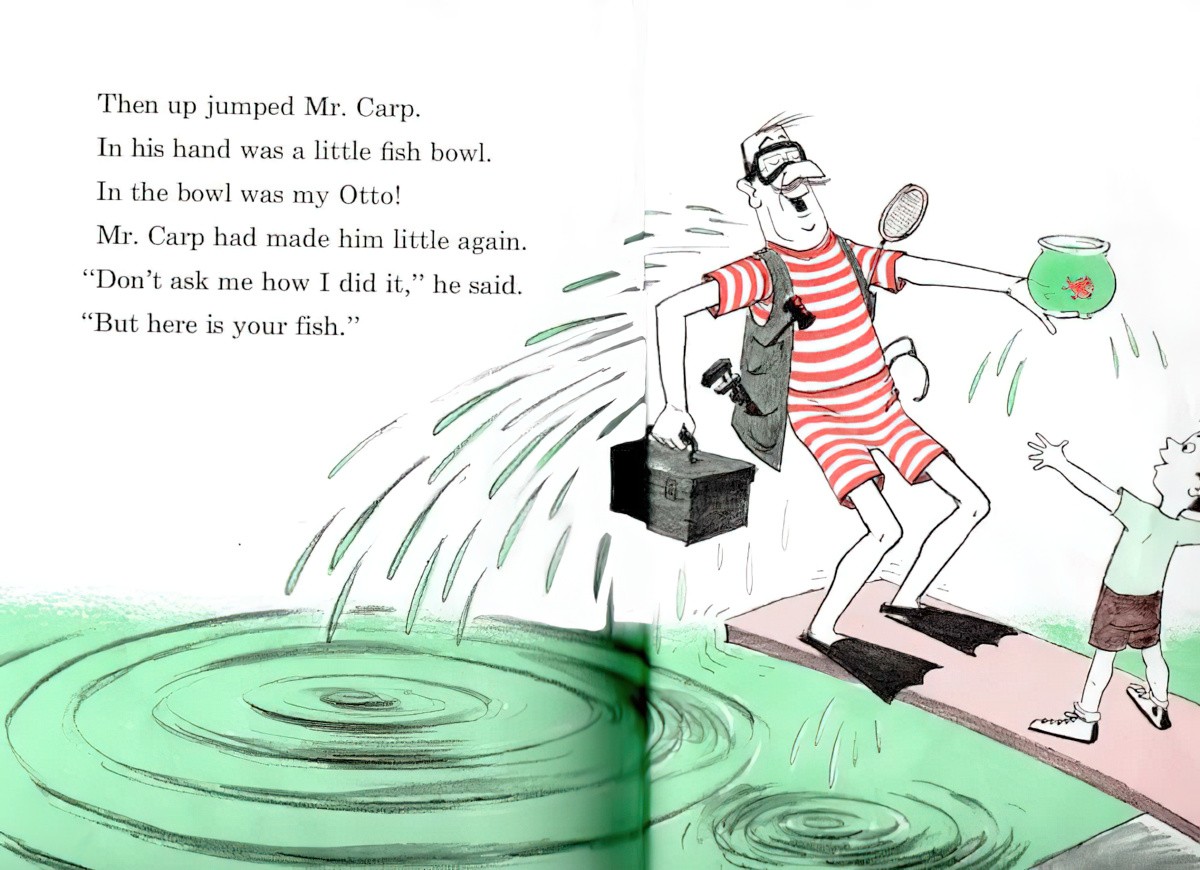

The writer cheats. We see the fish seller dive into the pool and do something to the fish. The fish becomes small again. The boy (and reader) is told to not ask what was done.

This is the wrong way of using magic in stories. The audience must know the basic rules of the magic even though magic, by its very nature, is mysterious.

NEW SITUATION

The boy takes the fish back home and will never feed it too much again.

In the end, this is a moralistic tale about the common childhood tendency to overfeed fish in bowls.

THE TEXT

The scansion and rhyme of this story is not up to the same standard as Theo’s other books. This is clear from the very first page:

“This little fish,”

I said to Mr Carp,

“I want him.

I like him.

And he likes me.

I will call him Otto.”

Reading that, you get the feeling it should rhyme but doesn’t quite. Overleaf, we do have some rhyme:

“When you feed a fish,

never feed him a lot.

So much and no more!

Never more than a spot!

This is why, when writing a picture book, decide whether you want it to rhyme or not and then stick with your decision.

In conclusion, Theodor Geisel put this book aside for good reason. But I’m glad it exists, as a lesson in what doesn’t work, and also to know that even the masters like Dr Seuss didn’t write a winner every single time.