I’m sure any visitor to this blog has at least one version of Snow White on their childhood bookshelf. Which version did you have? When you think of Snow White, perhaps you think fondly of the Disney film, or perhaps, like me, you grew up with ‘Read It Yourself’ versions, as well as coming across it again in fairytale anthologies.

If you’d like to hear “Snow White” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Snow White” was published in two parts in November 2020.

The Snow White Project is a collection of various Snow White stories from around the world.

The Fairest of Them All by Maria Tatar review – the many faces of Snow White from The Guardian is a review of a book about Snow White stories from around the world by Maria Tatar.

Precisely because Snow White is such a widely anthologised and adapted fairy tale, it makes for an interesting case study into what to do and what not to do when faced with the joy of adapting — or re-visioning — a classic tale. You may have noticed that new versions of Snow White keep coming out, more and more each year, so it seems. But since none of us can own all of them, which versions are the very best? And which should you probably relegate to the bin?

I draw heavily from the writing of Jack Zipes and Perry Nodelman when coming up with best suggestions, and why.

A few things to know first

- Zipes is careful to point out that there is no single Grimms version; there never is — the Grimm Brothers collected various versions of all the main fairytales. (They were primarily collectors of fairytales rather than children’s authors.) Nevertheless, American translations tended to reproduce the archaic British English language of the nineteenth century. (Not including Wanda Gag’s translations, who was a feminist and free-thinker and did her own thing.)

- In recent years, variations of well-known fairy tales have become something of a fad in publishing for children.

- Fairy tales were never written for children, because the concept of ‘child’ came after the fairytales/folktales themselves. Tales such as Snow White were first designed for children when the Grimm brothers wrote them down, hoping to make some money to live off by marketing the folklore they’d collected at children.

What can explain the enduring appeal of the Snow White fairytale? Jack Zipes summarises it in his book Sticks and Stones:

I should like to suggest that Snow White appeals to both children and adults because she embodies the embig struggled child, abandoned by her father, persecuted by a stepmother, used by male dwarfs, and revived from death by a prince. As a fictional figure, Snow White reflects and recalls how adults are engaged in determining the welfare and fate of children. It is a tale about hierarchical conflicts and the powerlessness of the child. Snow White must fend for herself, defined herself, but she is not in charge of her destiny. She needs a miracle, as most children continually need miracles in their daily lives to intercede on their behalf. Not that children are victims or are constantly victimized. But their lives are framed by adults who seek to play out their lives through children.

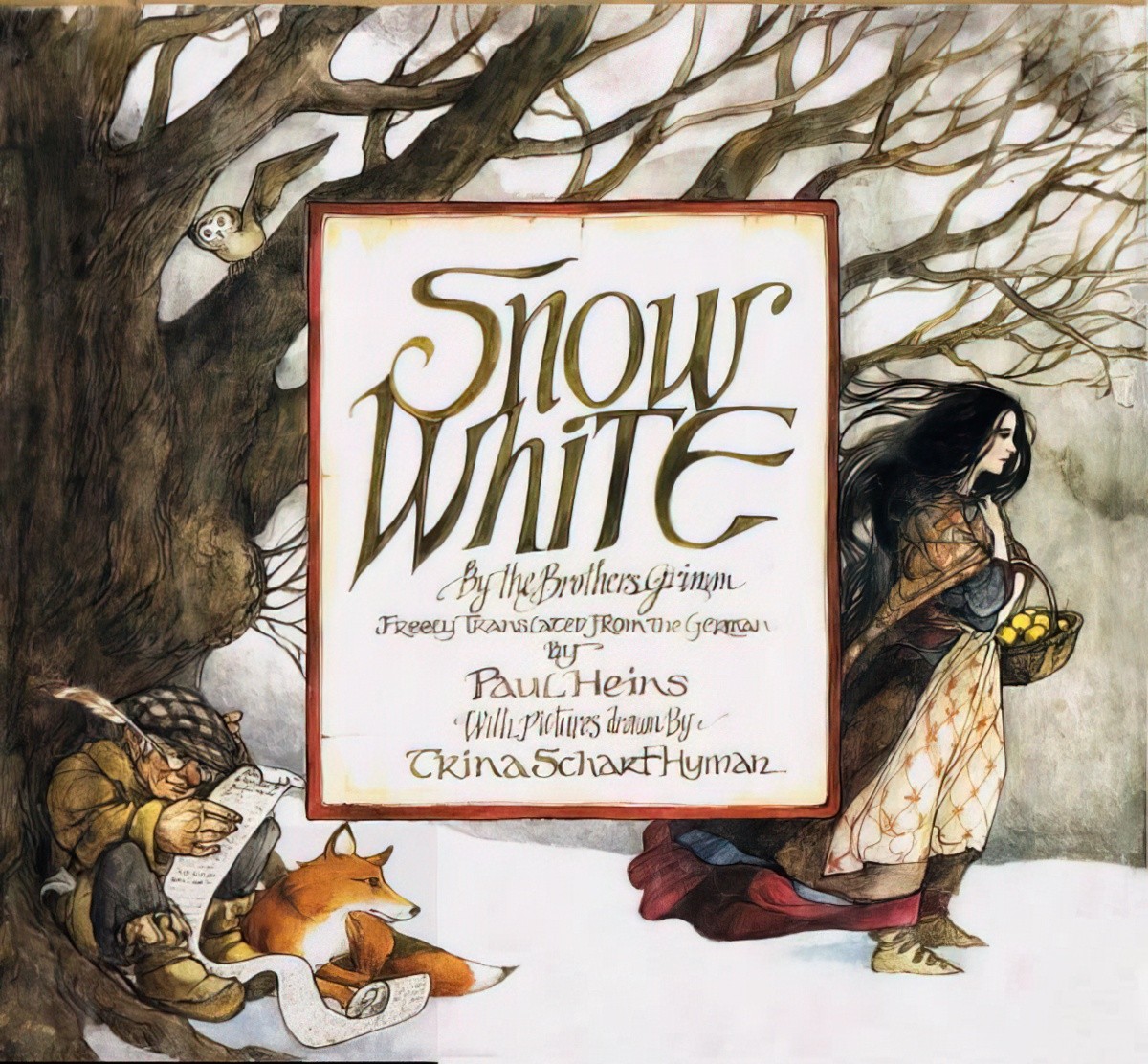

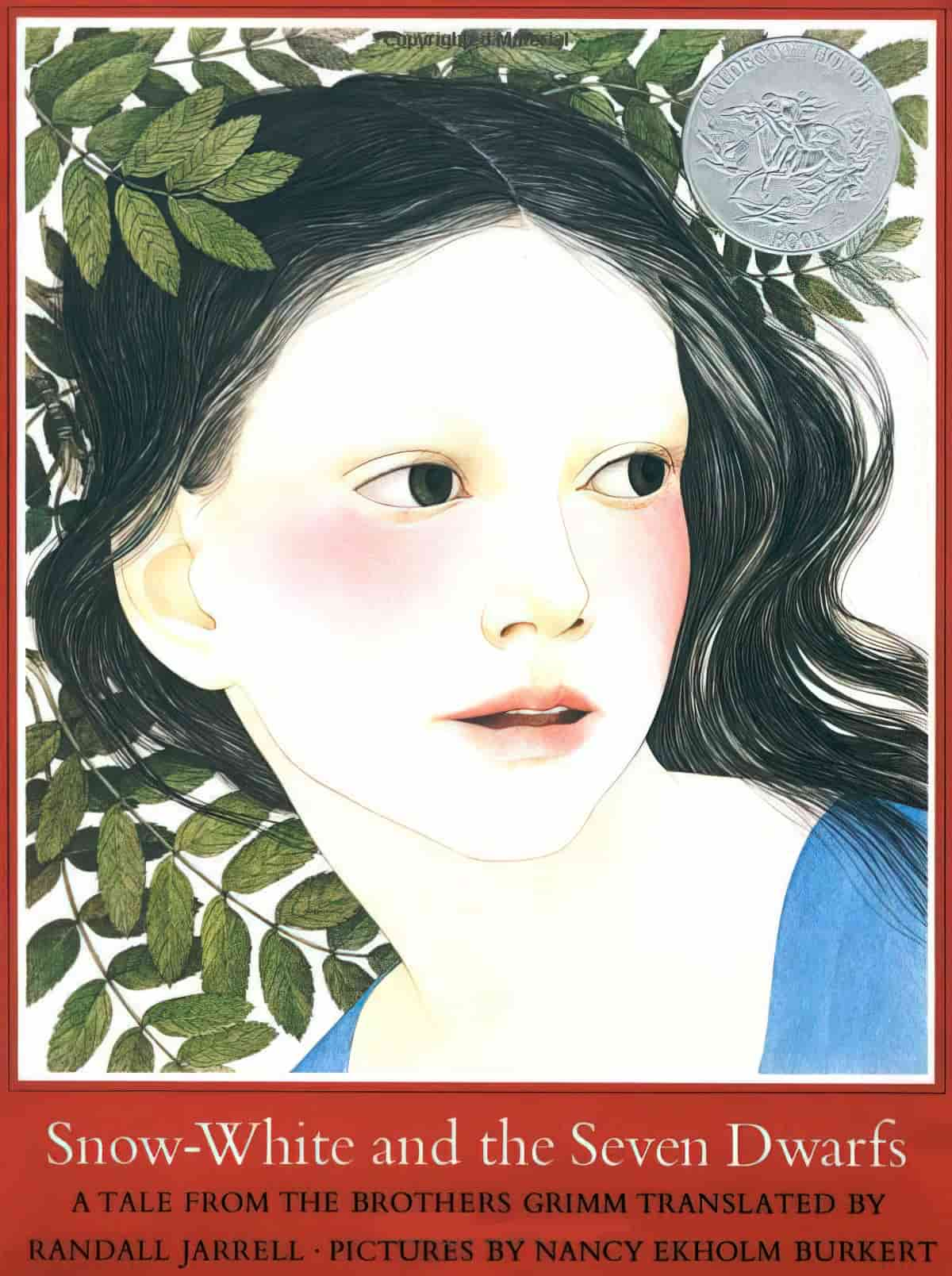

Nancy Ekholm Burkert and Trina Schart Hyman

Here’s the too-long-didn’t-read version, for those wondering which versions of Snow White to buy for a young reader:

Because styles speak so strongly of the values of those who originated them, illustrators who borrow them may even evoke ideas and attitudes of which they are not themselves consciously aware. While illustrating “Snow White”, neither Nancy Ekholm Burkert nor Trina Schart Hyman could have been conscious of the interpretation of the differences between traditional Dutch and Italian painting that Svetlana Alpers proposed many years after their work was finished; yet Human’s work, vaguely Italianate in style, certainly seems to express the values Alpers finds in the art of the Italian Renaissance, and Burkert’s pictures, more than vaguely similar to paintings in the Dutch style, are likely to evoke from sensitive viewers the same interpretations as those Alpers gives to Dutch art. Presumably, Hyman and Burkert consciously or unconsciously knew and wished to express what these styles signified, even if they would not have put it in the terms that Alpers’s insightful analysis provides.

Words About Pictures by Perry Nodelman

WONDERFULNESS

To sum it up:

The Hyman and Burkert versions are the most successful picture books of this group, and not just because they happen to contain the most complex and satisfying pictures; they also both have the contrapuntal narrative rhythms that we expect both of good fairy tales and of good picture books. Hyman and Burkert have created authentic picture-book stories by distorting rather than duplicating the intentions of the original text. The directions of their distortions create highly distinct stories with clearly define styles, so that they have both done what all good storytellers do: they have told their own personal versions of familiar tales well enough to make them convincing. Such versions may well be the only “authentic” fairy tales.

Perry Nodelman

Nodelman uses Snow White (the various versions) as an example when explaining the nature of irony between pictures and words in picture books:

In a sense, the words of picture books are like a voice-over narration in a film that tells us what to see in the pictures, how to interpret them. But since the pictures themselves tend to the objectivity of the theater, there is an ironic distance between the subjective focus of words and the objective wholeness of pictures; unlike film or theater, picture books can be both objective and subjective at the same time.

In fact, they almost always are. Words can tell us that Snow White’s mother pricked her finger and then looked at the snow and the window frame, but a picture that showed us just the pricked finger anda window frame and snow would make no sense to us. All the illustrations I know of this scene also include one other object that makes sense of all the rest: Snow White’s mother. And that creates an irony: the words allow us to put ourseles in her place and follow her actions; the pictures demand that we stand back and look at her—observe her actions.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS

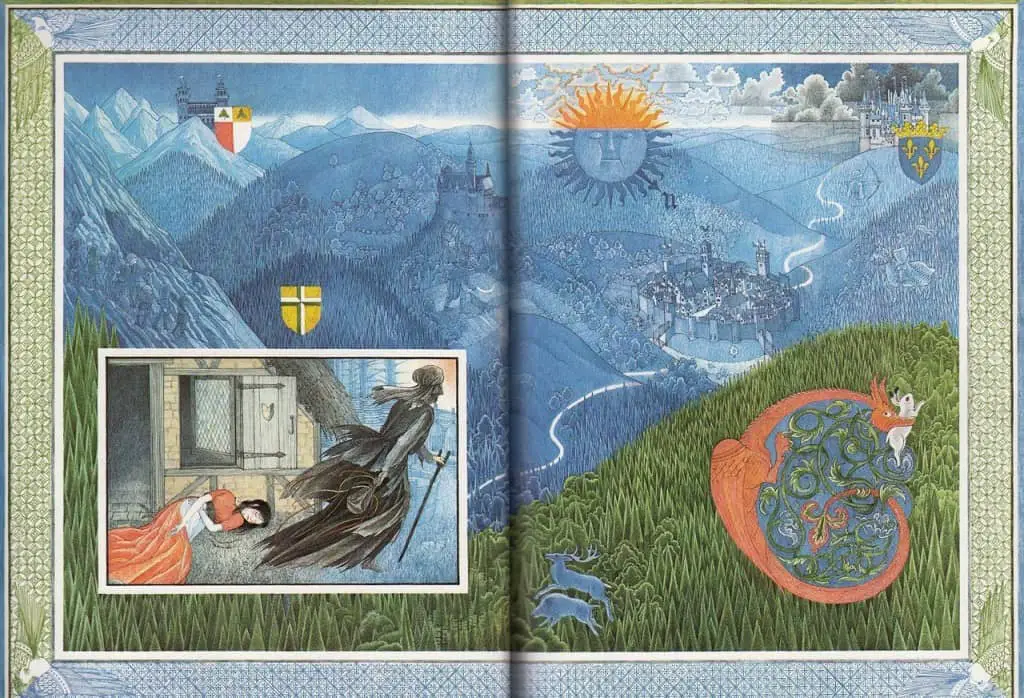

What to look for when assessing how well a modern illustrator has illustrated a classic tale, or any tale, for that matter? It’s all about which moments they choose to depict. Nodelman calls the main plot points in a story ‘key moments’, and if take a stack of Snow White books out of the library, you’ll see the exact same key moments illustrated over and over again. But every now and then you’ll come across illustrators who decide to do something a bit different, and they will show you pictures not often seen in other adaptations. Sometimes they’ll show you a scene from a different point of view; other times they’ll take the moment just before or just after the ‘key moment’:

[T]he moments […] illustrators choose to depict and the rhythms that result from the combination of those moments with the words of a text are the qualities that most significantly give rise to the individual flavour and meaning of their versions. They are also the features that most specifically make use of the distinguishing ciharacterteristics of picture books as a medium of narrative communication. All kinds of pictures can convey visual information and create moods; all illustrations can amplify the meaning of a text. But it is the unique rhythm of pictures and words working together that distinguishes picture books from all other forms of both visual and verbal art.

Perry Nodelman

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

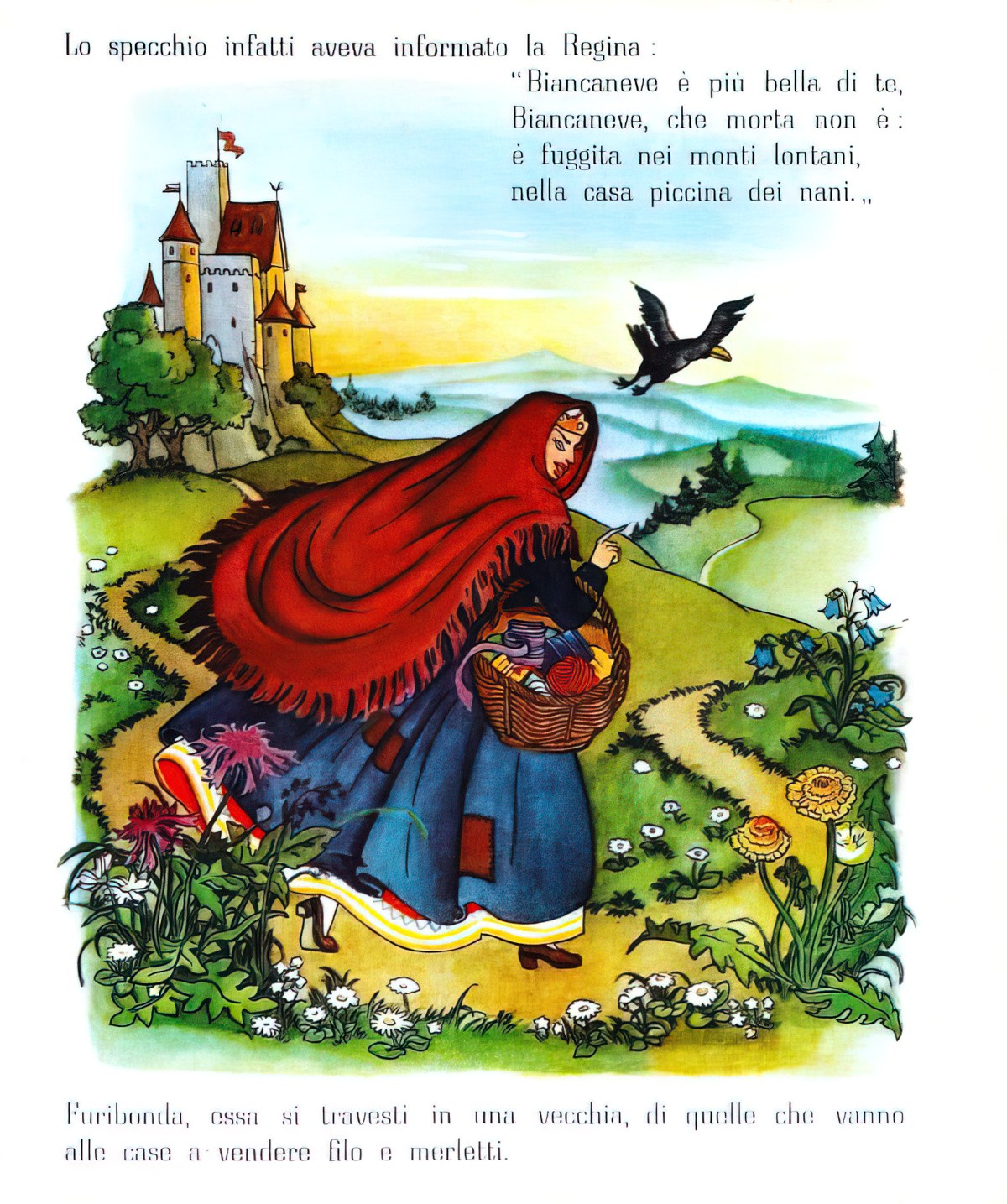

SNOW WHITE IN EUROPE

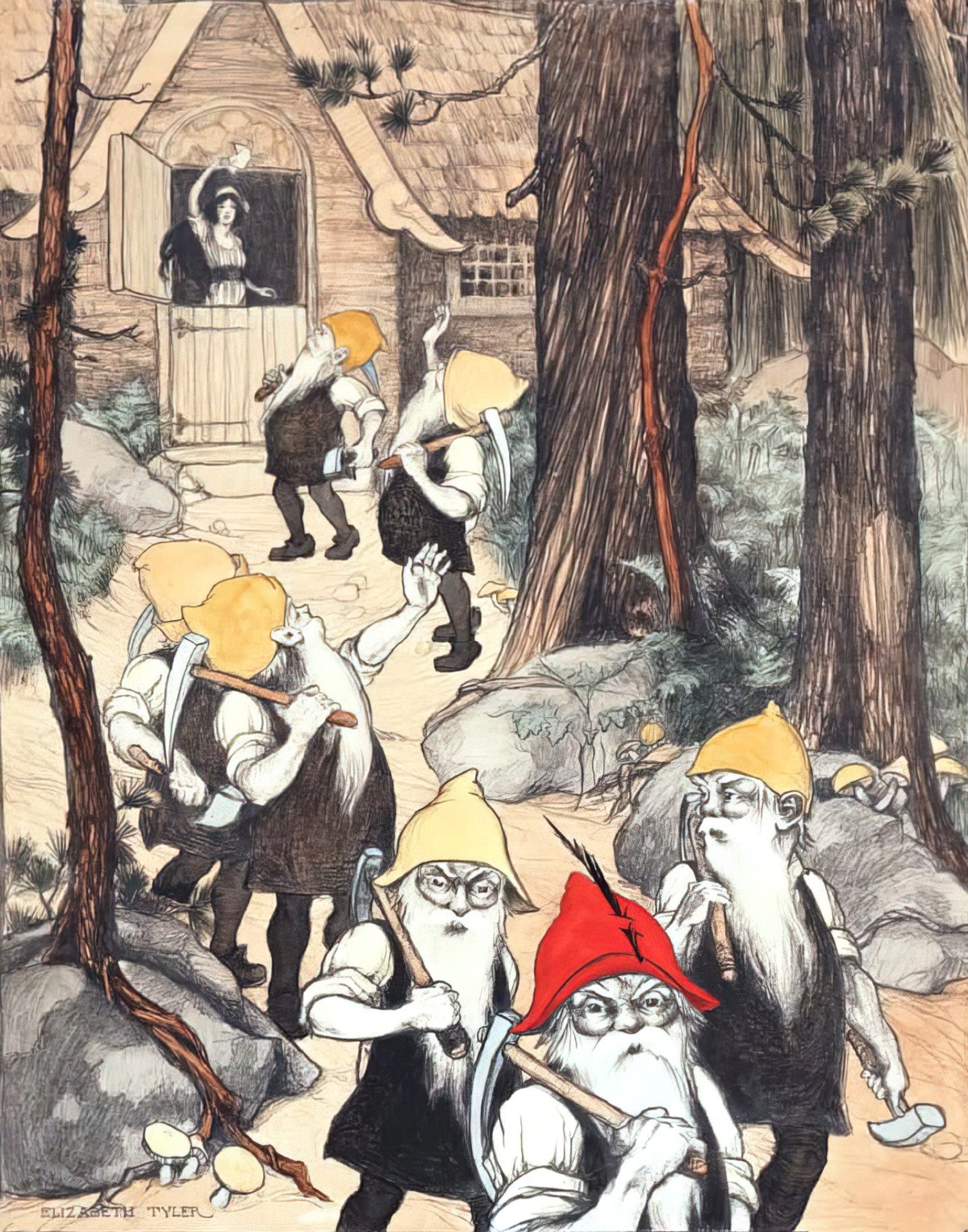

Arthur Rackham

Arthur Rackham (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator.

SNOW WHITE IN AMERICA

The following were big names in American fairytale illustration in the first 30 years of the 20th Century:

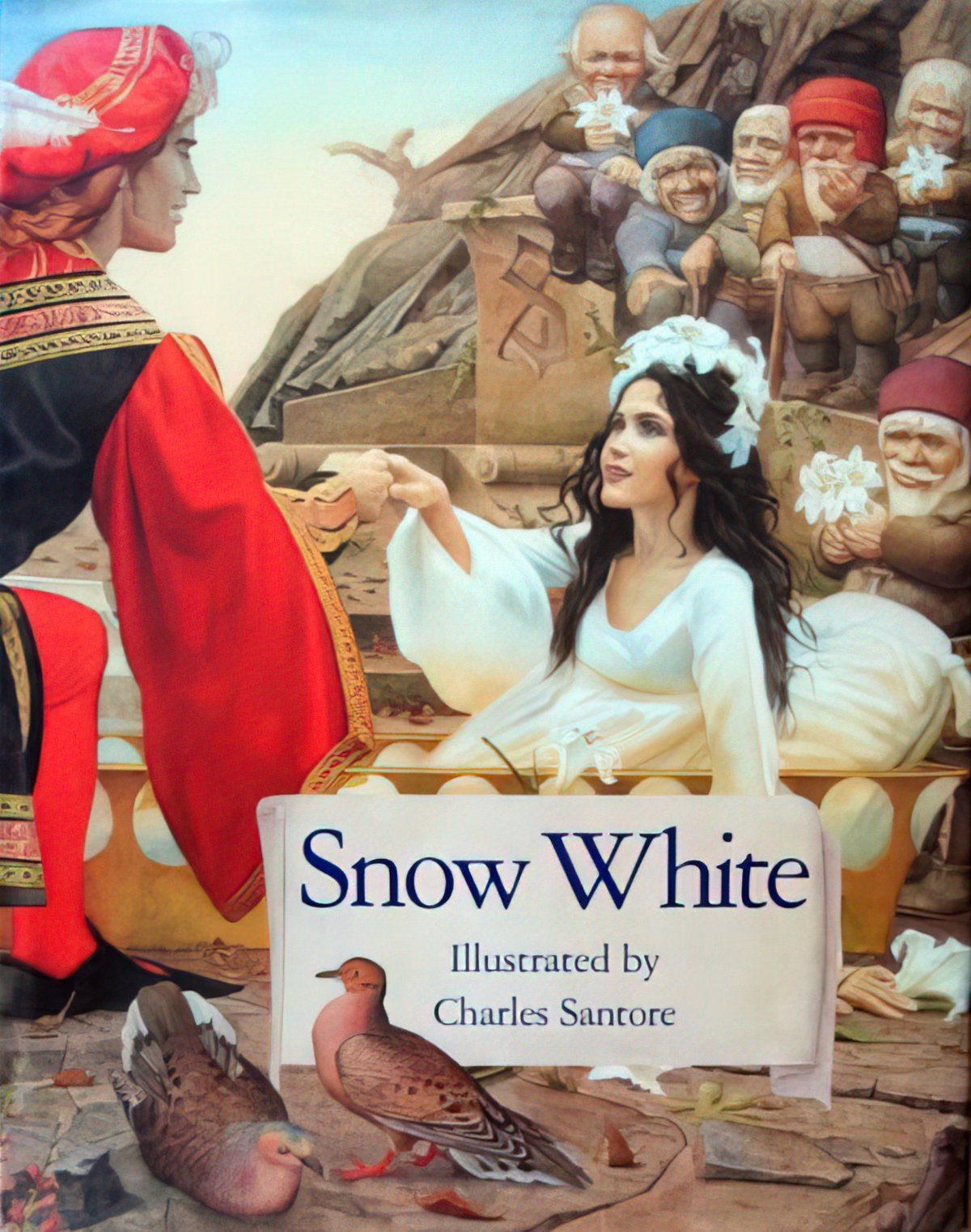

Charles Santore

Charles Santore is an artist in Philadelphia who spends two years on each book he illustrates.

Wanda Gag

In Sticks and Stones, Zipes talks about Gag’s role in bringing the tales of Grimm to an American audience in the 1930s and 1940s, ‘just at a point when anti-German sentiment was once again on the rise’. Fairytales had become very popular in America during the first 30 years of the 20th century.

Wanda Gag spent the entire last 20 years of her life devoted to fairytales — she was concerned with preserving the spirit of the original German sensibility. (She herself was of German heritage, though American born and never set foot in Europe.) She didn’t appreciate that Grimms’ fairy tales were during her lifetime being commercialised and bowdlerized. Jack Zipes is not all that impressed by her illustrations, however:

Gag’s illustrations, mainly black and white ink line drawings, are for the most part a disappointment, even though they were non-traditional for her time. While pleasing to the eye, they do not add depth to the texts. In fact, they take away from her translations and even contradict them. In Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, for example, Snow White is more like the seven- or eight-year-old Dorothy of The Wizard of Oz, and it is difficult to imagine her being attractive to any prince. Her stepmother is much more alluring than she is. Gag is at her best when she includes landscapes in her illustrations. Her ink drawings have a naive and almost childlike quality to them that makes them soothing but somewhat boring at the same time. There is no dramatic tension in her illustrations, or nothing that adds to our understanding of the possible psychological conflicts or social background of the stories. Gag never probed the tales; she re-created them in her own spirit. She made them into idyllic moments of pleasurable reading and seeing for her readers, children and adults alike. Her longing to recapture the Grimms’ tales was actually a utopian projection of possible happiness. The joyful simple figures point toward a simplification of life, a desire for “genuine” living, which was ironically one of the reasons that her work was somewhat pivotal in the debate about fairytales at that time.

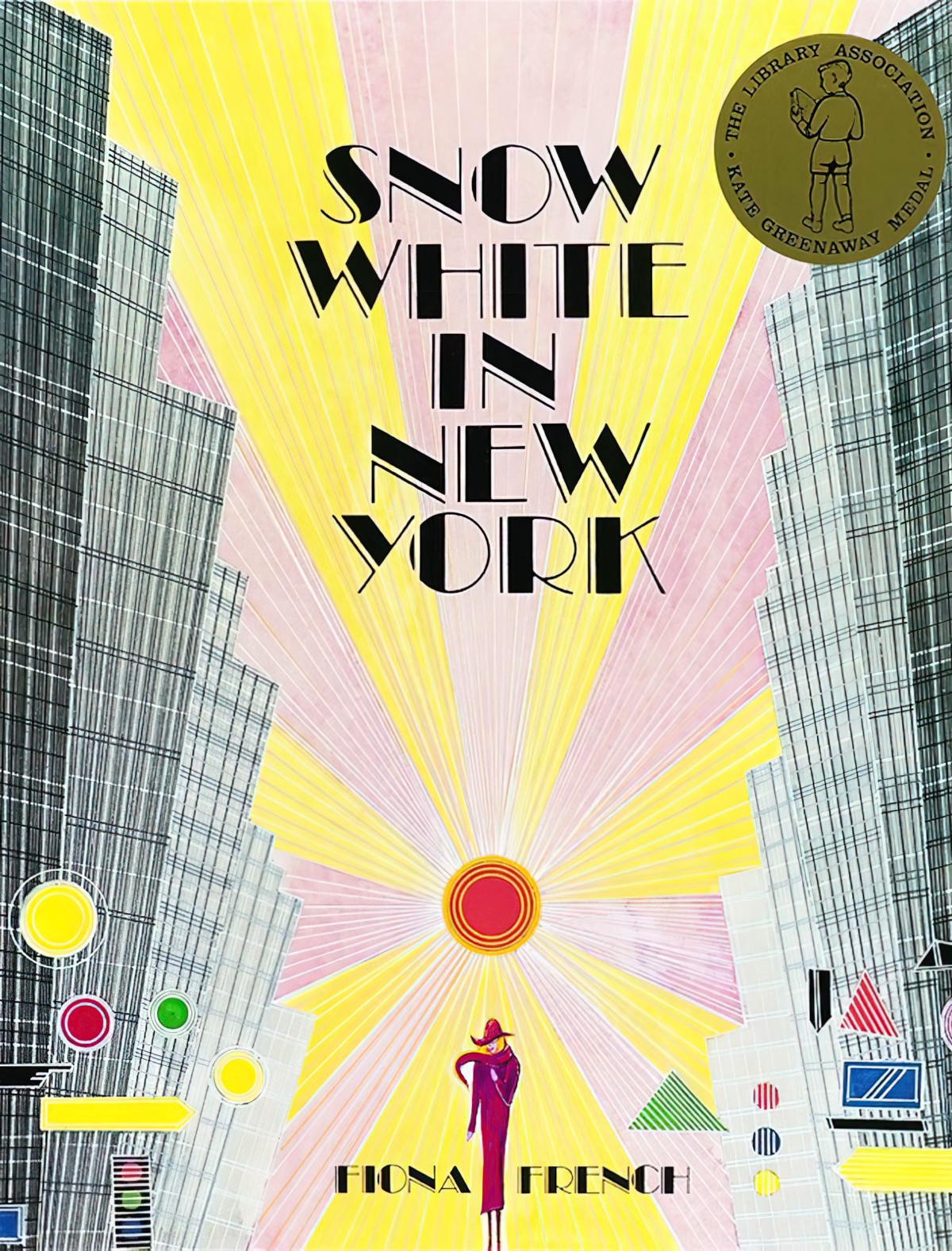

Snow White In New York by Fiona French

French’s Snow White In New York describes how a poor orphan, mistreated by a wicket stepmother, finds herself alone on the dark, wild streets of the urban jungle, until she’s taken in by seven kindly jazzmen and then rescued by a handsome reporter for the Daily Mirror. {…} [This allows] readers the pleasure of using schemata. Readers can recognize a pattern they’re familiar with. Then, because they can do so, they can perceive and understand the significance of divergences from it. {…} readers can enjoy the clever commentary on modern life implied by the fact that the mirror and the wild forest of tradition have been replaced by a newspaper and a typical modern city street.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

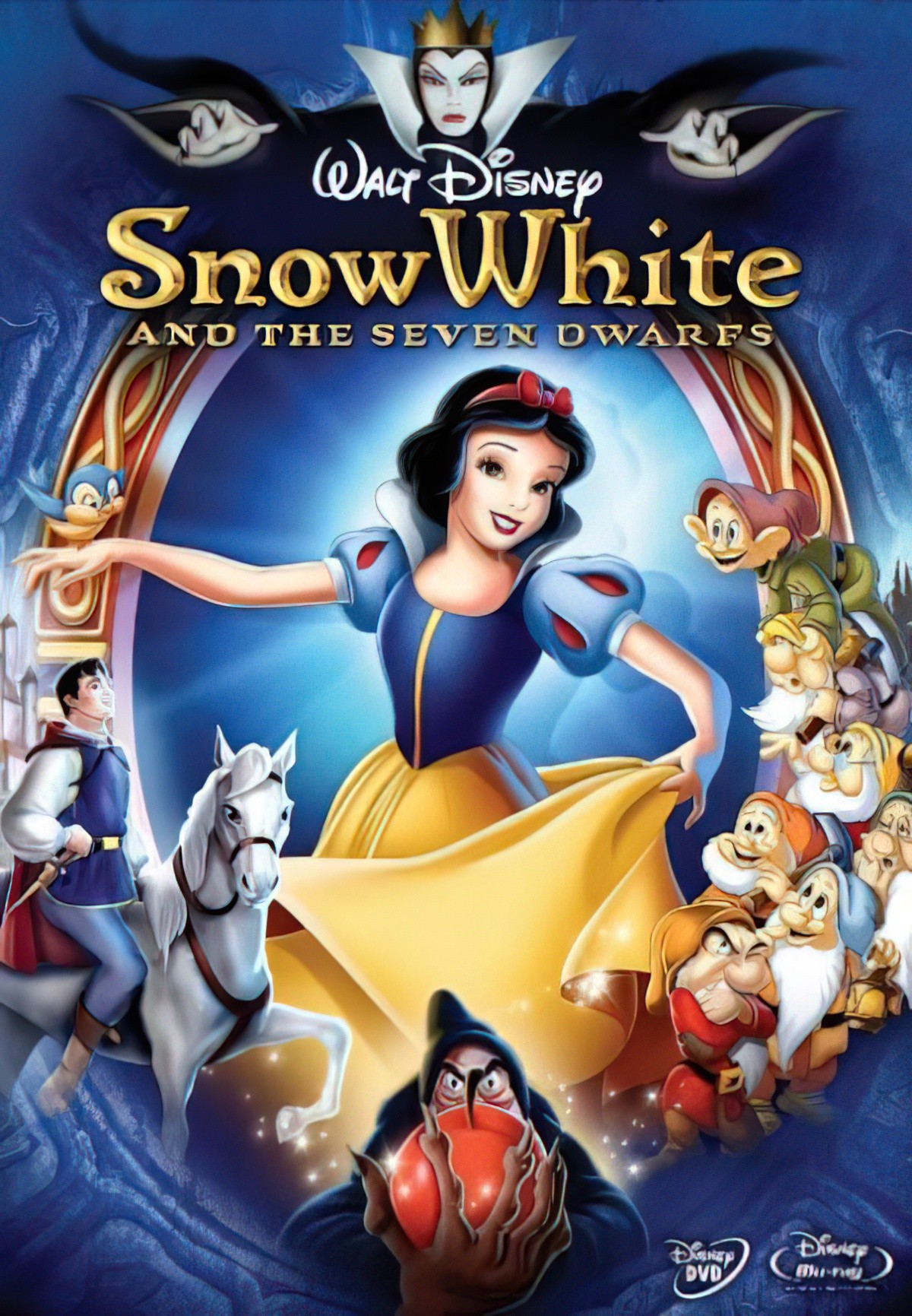

Walt Disney

Perhaps the single biggest influence in keeping Snow White alive for modern audiences is Walt Disney, who adapted Snow White for an American audience in 1937.

Disney had begun making black-and-white fairy-tale films that were to influence the book publishing industry. Very few critics have remarked on the fact that the “German” fairy tales became fully “contaminated” by American artists and writers during the 1930s, especially in the Disney studios. The features of Snow White and her Prince Charming represent the all-American “healthy” ideals of beauty, prefiguring the Barbie and Ken dolls by a good twenty-five years, and the language and jokes in the film are clearly tied to American idioms and customs. Disney’s success in creating his Snow White depended on his deep understanding of the dreams and aspirations of Middle America during the 1930s and how Americans received fairy tales. The introduction of music, sight gags, comic diversion, and Technicolor transformed the story of Snow White into a typical Broadway or Hollywood musical that had little to do with German folklore. Other American animators followed suit in the late 1930s and early 1940s. What had formally appeared in the collections of fairy tales by the Grimms, Perrault, and Andersen in book form were now mocked and turned into comic entertainment in America.

Jack Zipes, Sticks and Stones

The Walt Disney film has been so influential that it shapes readers’ expectations of what to expect from books. Here is one rather comical review from a Snow White adaptation on Amazon:

Yet until Disney came along, the dwarfs didn’t have names, because the story wasn’t about them. Nor were they miners. That was another Disney invention, though many young readers will tell you most definitely that the dwarfs must be miners by trade.

SNOW WHITE IN ENGLAND

Nosy Crow

Disney and Pixar have been part of the trend towards the ‘babyfication’ of female characters, which is now emulated (probably subconsciously) by many illustrators. Here’s the large-eyed, beautiful Snow White depicted on Nosy Crow’s Snow White app icon:

Perry Nodelman summarises the main problems with some of the most popular publications of Snow White throughout the 80s and 90s to today:

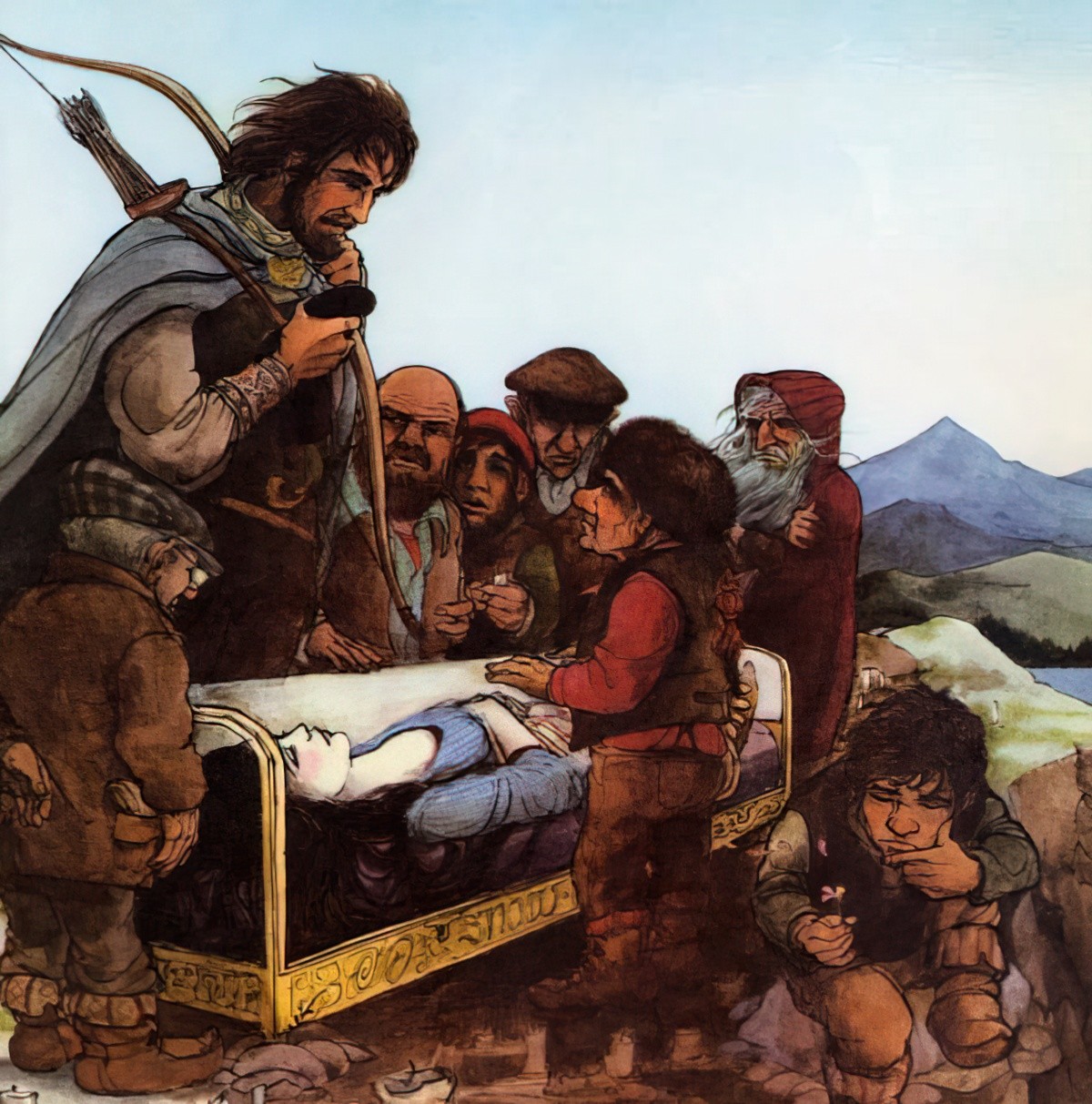

Illustrators of “Snow White” often ignore many of the spinal moments in favour of a single-minded concentration on dwarfs. Kent, Svend Otto S., Fritz Wegner, and even Wanda Gag provide a sizeable number of pictures with no particular purpose other than to show how adorably cute their dwarfs are. The ultimate example of how this story has become refocused around the charm of little creatures and away from its original interest in passion and retribution is the Walt Disney film version. A picture book of this film published by Golden Press contains so many pictures of Snow White cavorting with both forest animals and dwarfs that there is no space left for a depiction of the Queen’s demise or even of “Love’s First Kiss,” which is significantly featured in both the movie version and in the text of the picture book. Another Golden Press version that claims to represent Disney tells the story from the dwarfs’ point of view—it tells us how lonely they are, announces Snow White’s arrival—and then ends. The trouble with such stories is less their lack of authenticity than their inadequacy as stories in their own right.

Perry Nodelman

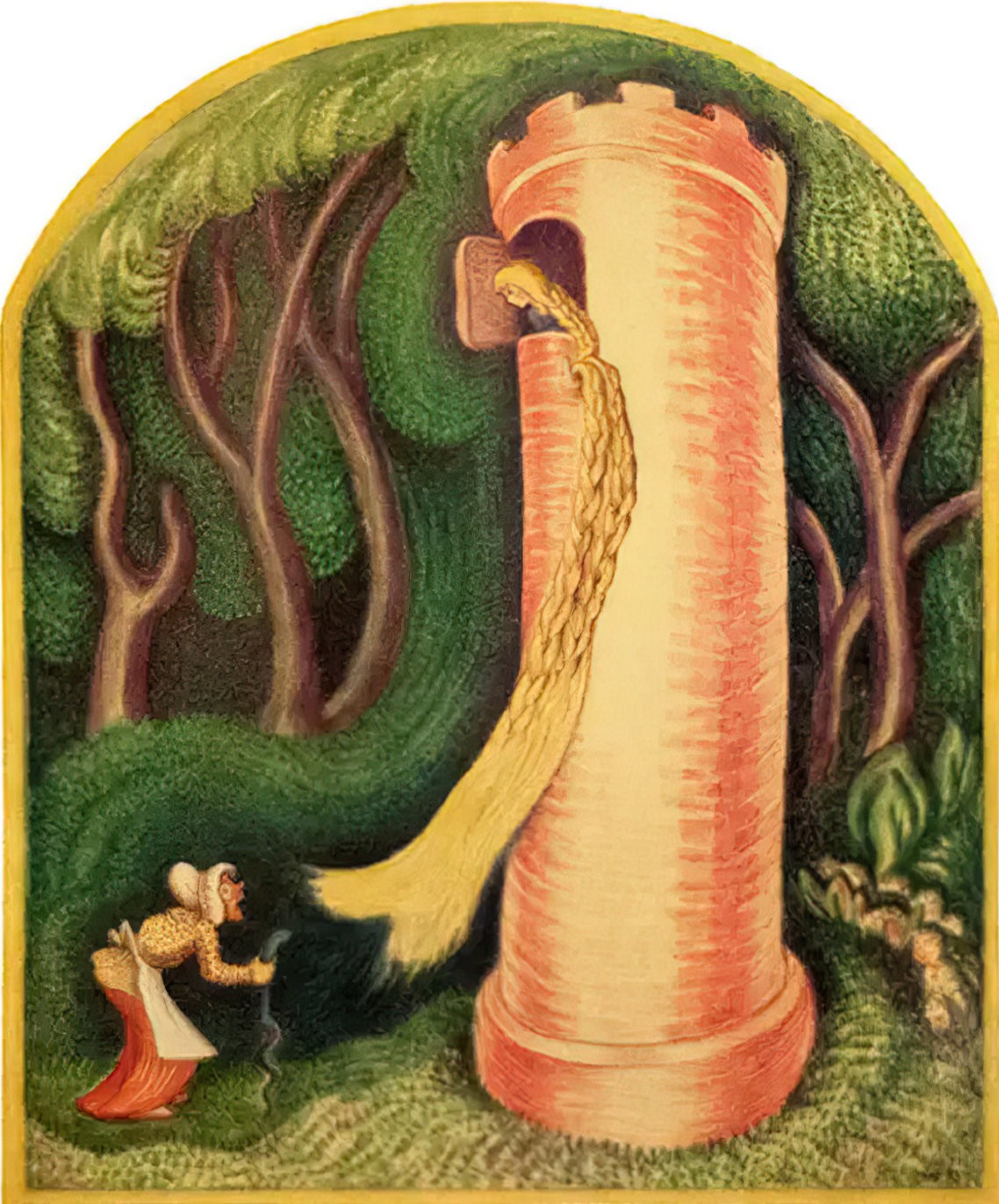

Basically, too much of the emphasis is on the dwarves, who were never meant to be ‘cute’. Looking at this trend from a feminist point of view, the tendency for modern, super popular versions of fairytales to focus on the male characters seems to be an attempt not to ‘alienate’ young male viewers, since it’s thought that boys shouldn’t/wouldn’t be interested in a tale starring a female protagonist. (Think of the movie Tangled, with its plotline dwelling upon the task of the prince, rather than upon the complicated relationship between Rapunzel and her mother. In the case of Snow White, what once passed the Bechdel test (by focusing the relationship between a mother and her [step-]daughter), is now about how the manic pixie dream girl enters the lives of seven lonely men and makes their lives better:

Not surprisingly, a number of cheap editions of “Snow White” I found in a discount bookstore also focused on dwarfs. But in these poorly drawn versions, the pictures tend to illustrate the key spinal moments more often than not—or at least, those which are not threatening, for there are few depictions of the coffin shattering, and none of the Queen’s demise. Furthermore, there are usually few other pictures in these books; they do tend to move neatly through the sequence of moments we might expect. If anything, the spinal moments are overemphasized; in the Lady Bird “Read It Yourself” version, the Brimax “Now You Can Read” version, and the Award Classic version, there are entire sequences of pictures that depict three of the central episodes: first, the Queen at her mirror, then Snow White exploring the dwarfs’ house, then the dwarfs finding Snow White.

Perry Nodelman

Nodelman explains that while all these versions focus on the act of seeing, they distort the emphasis of the original story, because readers are required to be interested in the wonderful things these characters see, not in how the characters respond to them.

These are “illustrations: in the most basic sense of the word: their purpose is to show what the objects described by words look like. Because they do little more than that, because they merely amplify the already amplified moments of the text, they do little to change the rhythm of the original story. In merely duplicating what we already have from the words, these pictures do not justify their own existence.

Perry Nodelman

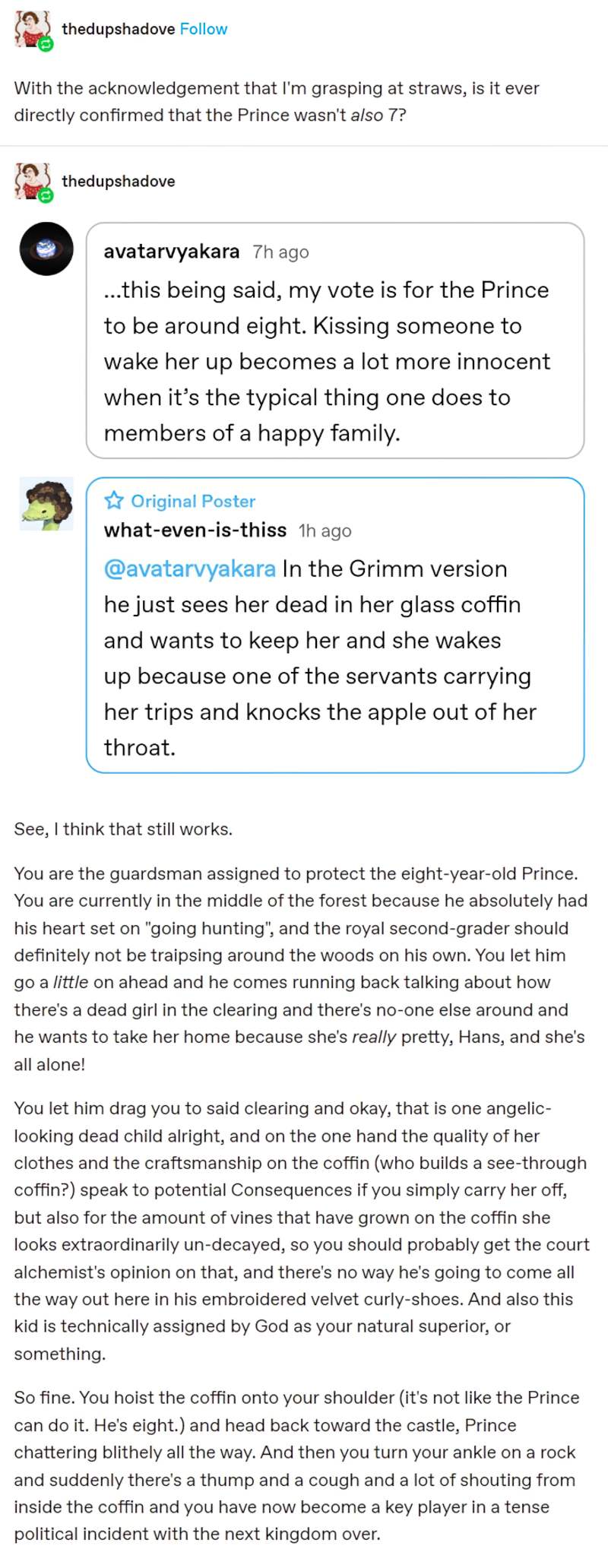

Snow White by Freya Littledale, illustrated by Susan Jeffers

This book is out of print and difficult to source these days, but Perry Nodelman picks it as an example of an adaptation in which the illustrations fail to sufficiently extend the story:

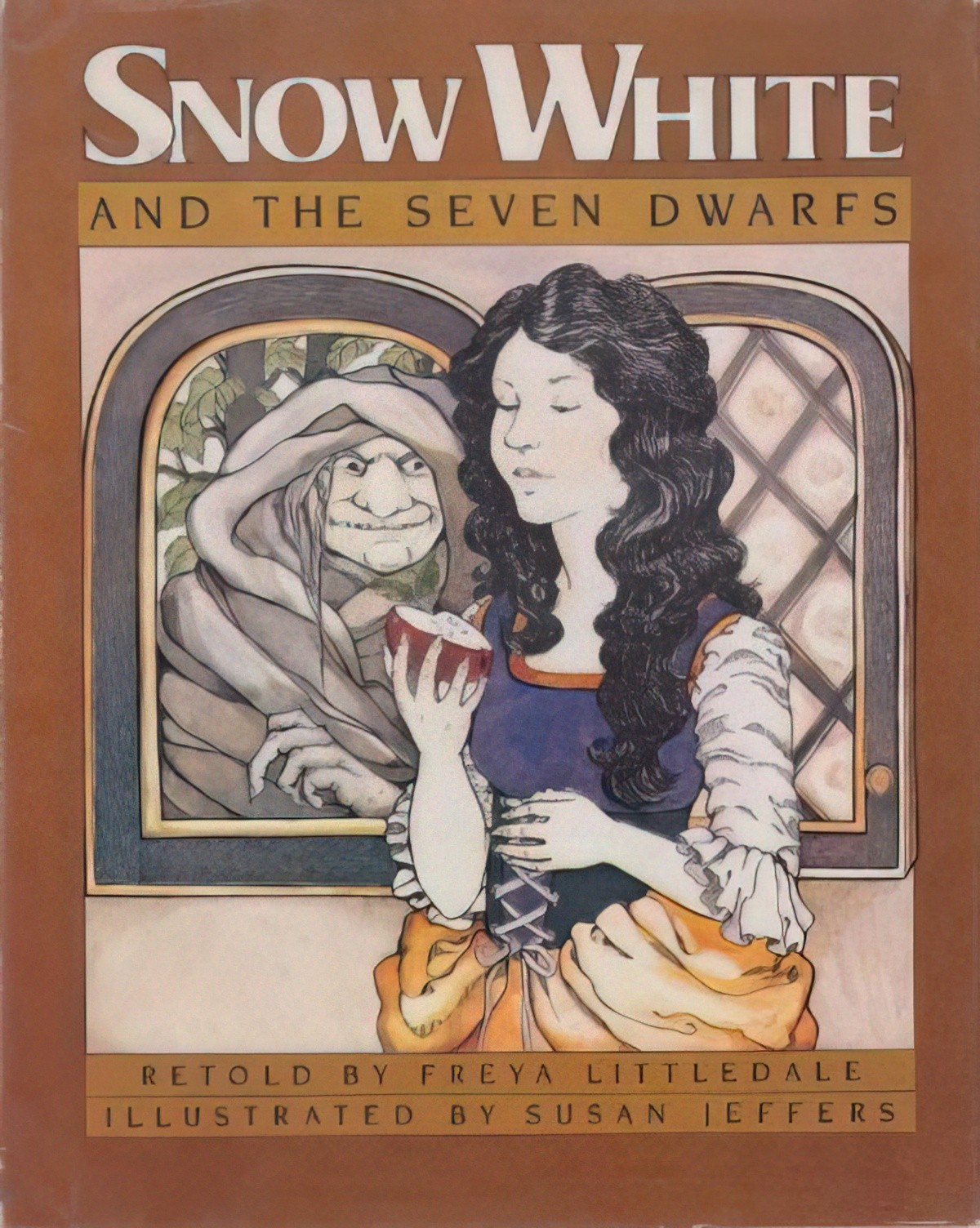

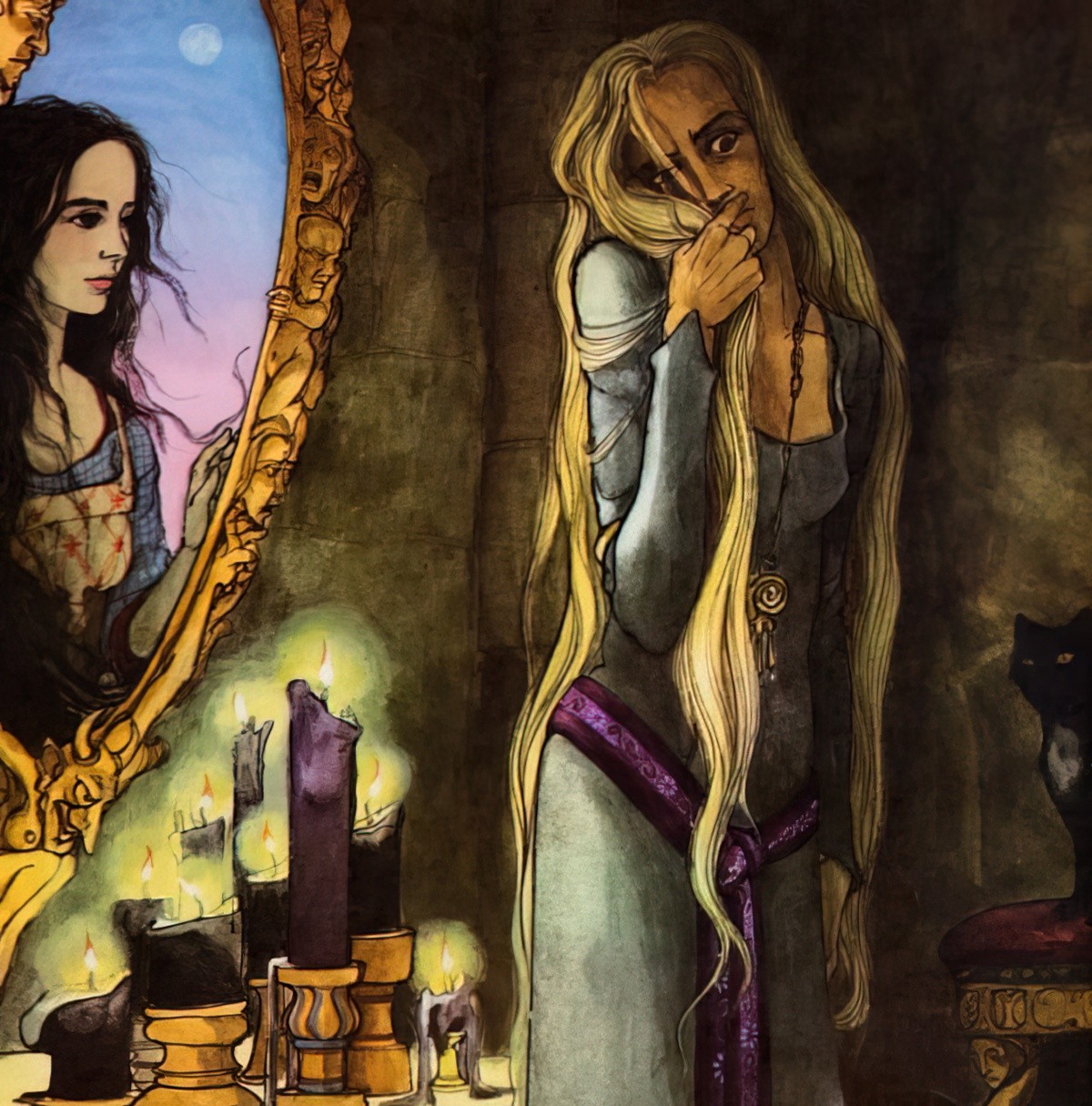

A glance at Susan Jeffers’s version of “Snow White” confirms that adherence to the rhythmic shape and focus of the original story may not be the best way to go about illustrating fairy tales. Of the versions of this story I have seen, this one comes closest to duplicating both the rhythm and focus of the the original. Jeffers depicts twelve of the key moments—all but the shattering of the coffin—and all the other pictures in the book add to the emphasis in these spinal pictures on looking and seeing. As in Human, almost every picture is in some way related to the idea of vision; people look at each other, or at objects, or out of the picture at us. But unlike in Hyman, and also unlike in the cheap versions, these pictures focus both on what is seen and how it affects the person who sees it. As well as seeing the Queen look in the mirror, we ourselves are drawn to look in admiration at the highly intricate pattern of her dress, and as well as looking at Snow White in the forest, we must look at all the interesting animals hidden in the foliage behind her. But despite this adherence to the patterns of the text, this “Snow White” is not one of Jeffers’s better books; it lacks a satisfying intensity because in merely duplicating the patterns and focus of the words, its pictures are more or less superfluous.

Perry Nodelman

Nodelman compares Jeffers’ humdrum illustrations with those of Burkert, who does a much better job of extending the story and creating atmosphere in her illustrations of the same classic tale:

Paradoxically, Burkert’s Snow White is more intensely affecting exactly because the detachment and objectivity of these pictures are not balanced by involving emotions. Both Jeffers and Burkert show Snow White in the wood surrounded by animals hidden in foliage, but Jeffers’s Snow White stares at them in obvious anguish, so that the detachment required by our act of finding all the animals is diluted by the concern we are asked to feel for her—our involvement in her response to the situation. Burkert’s Snow White responds differently; she seems to notice none of the animals but an unthreatening deer, and the picture de-emphasizes her terror enough for us to remain detached observers as we look at it.

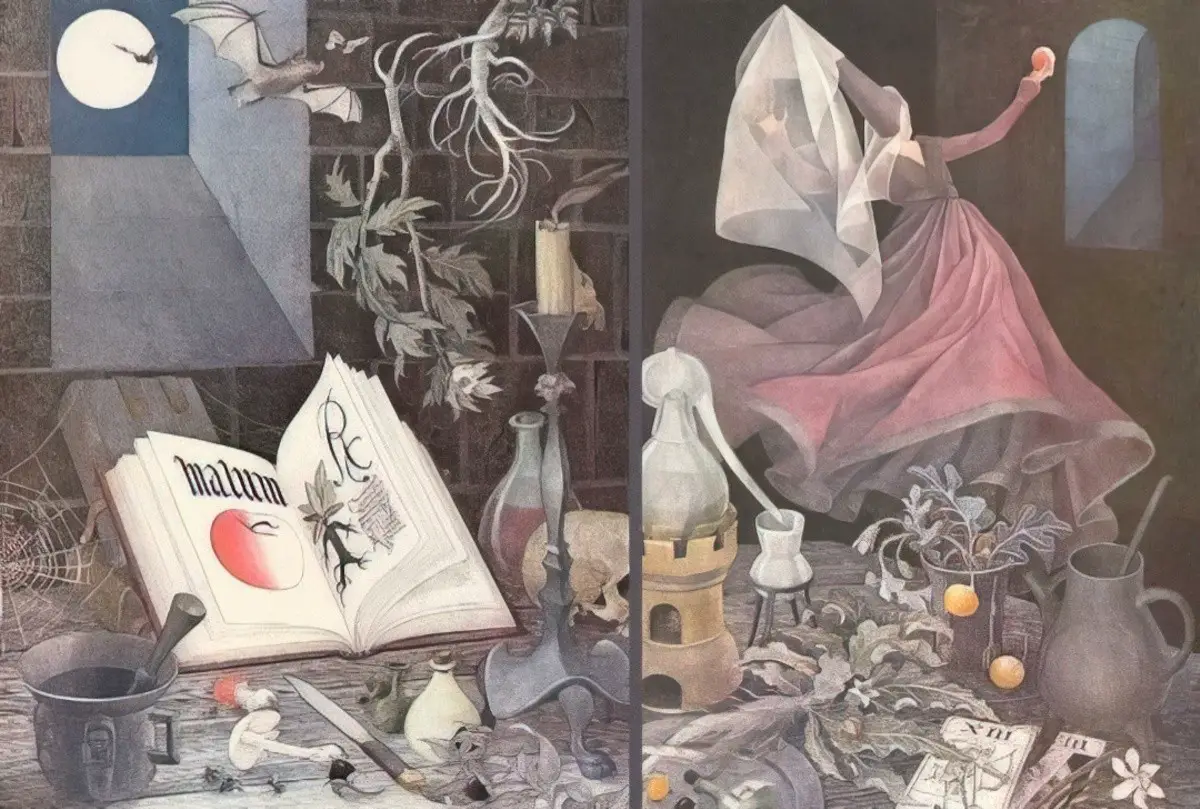

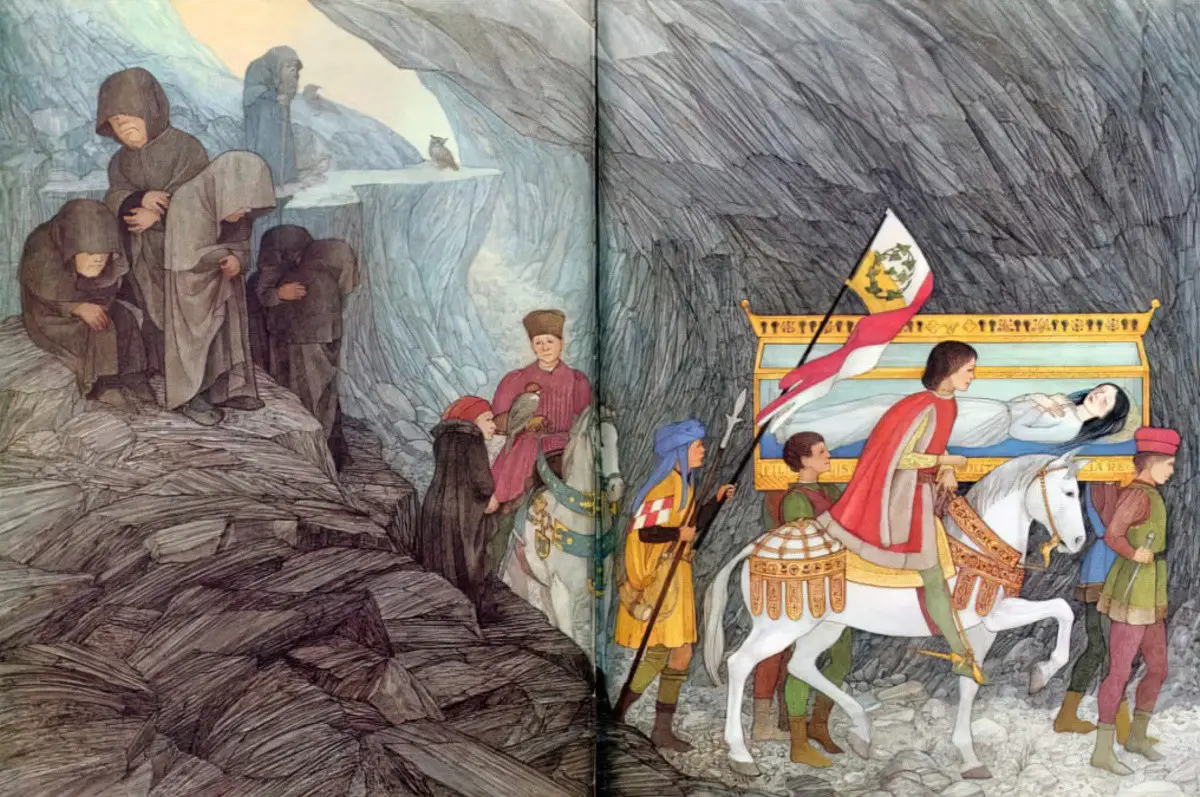

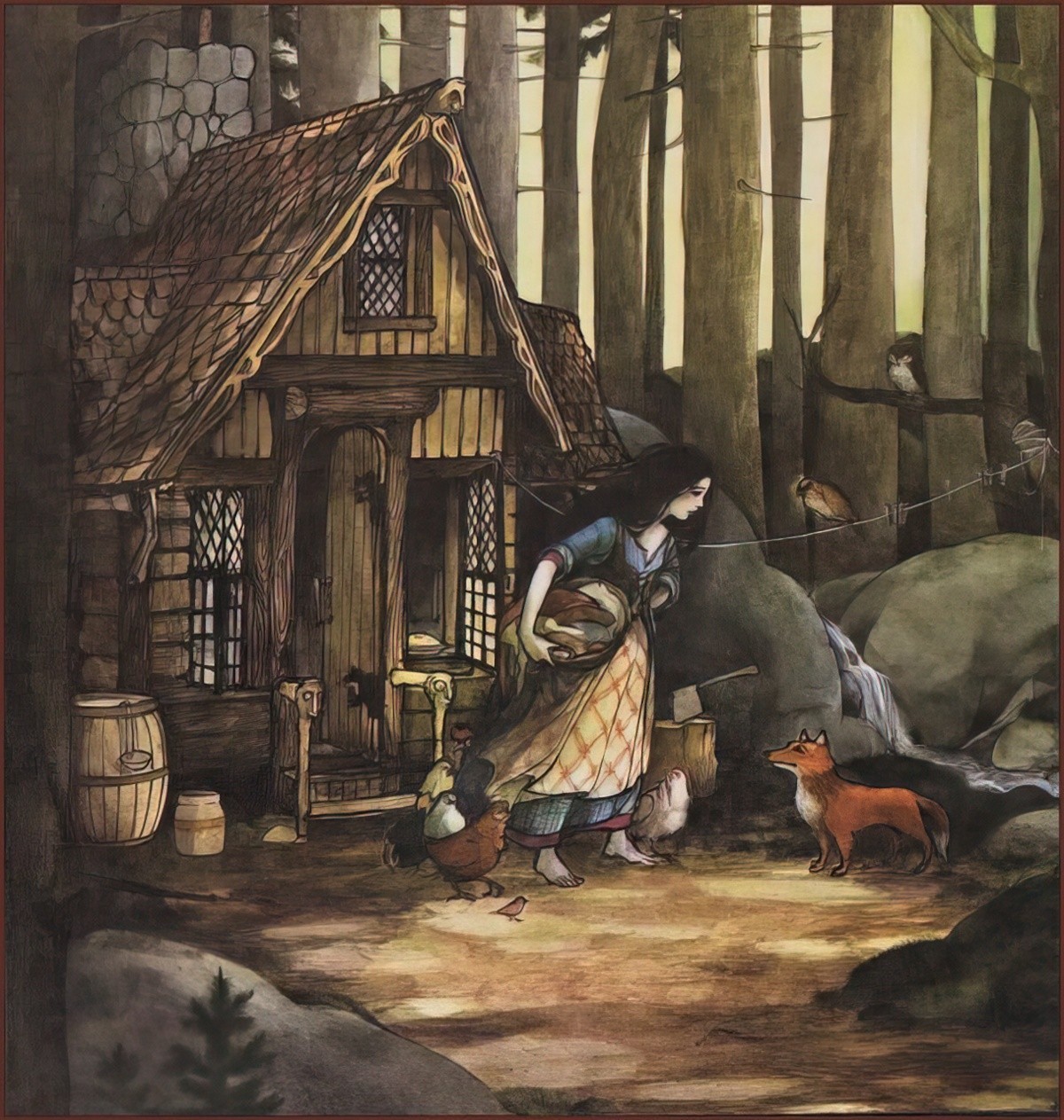

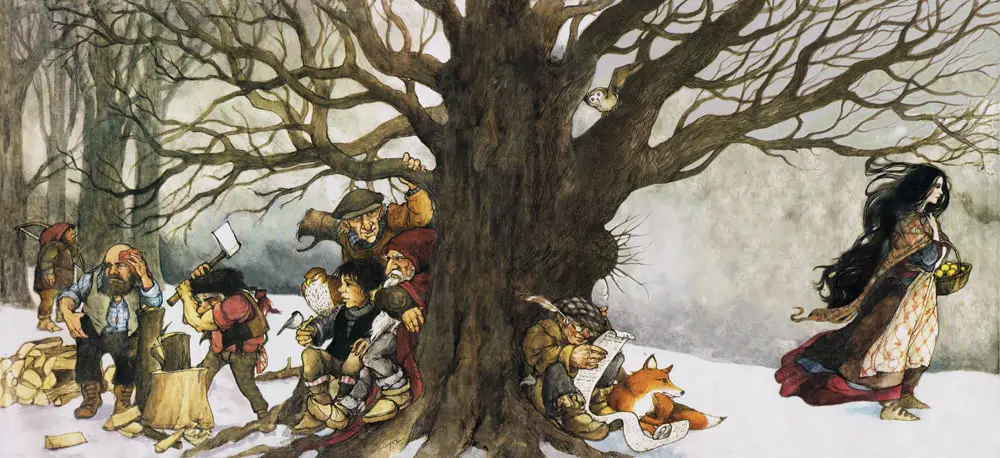

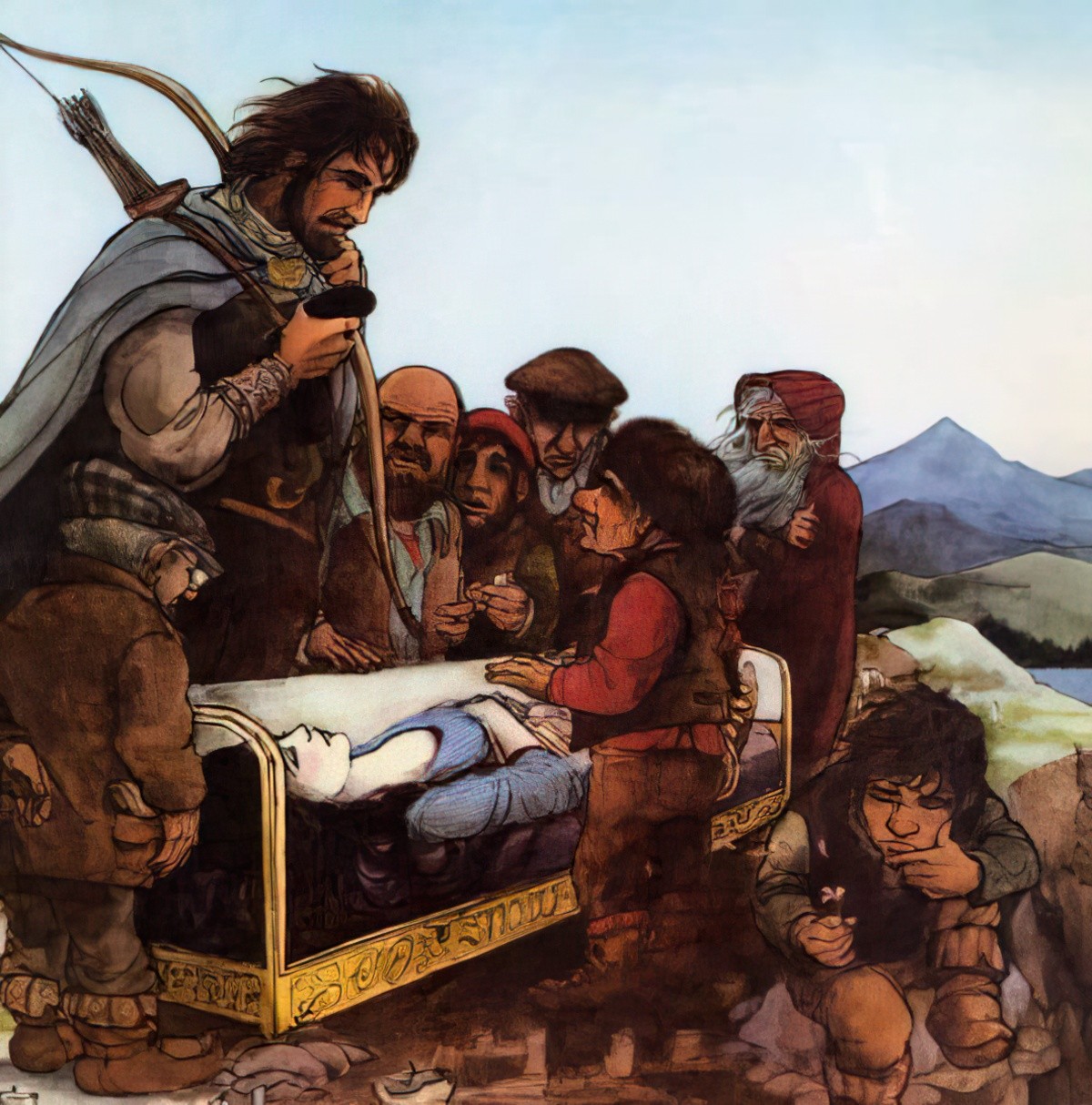

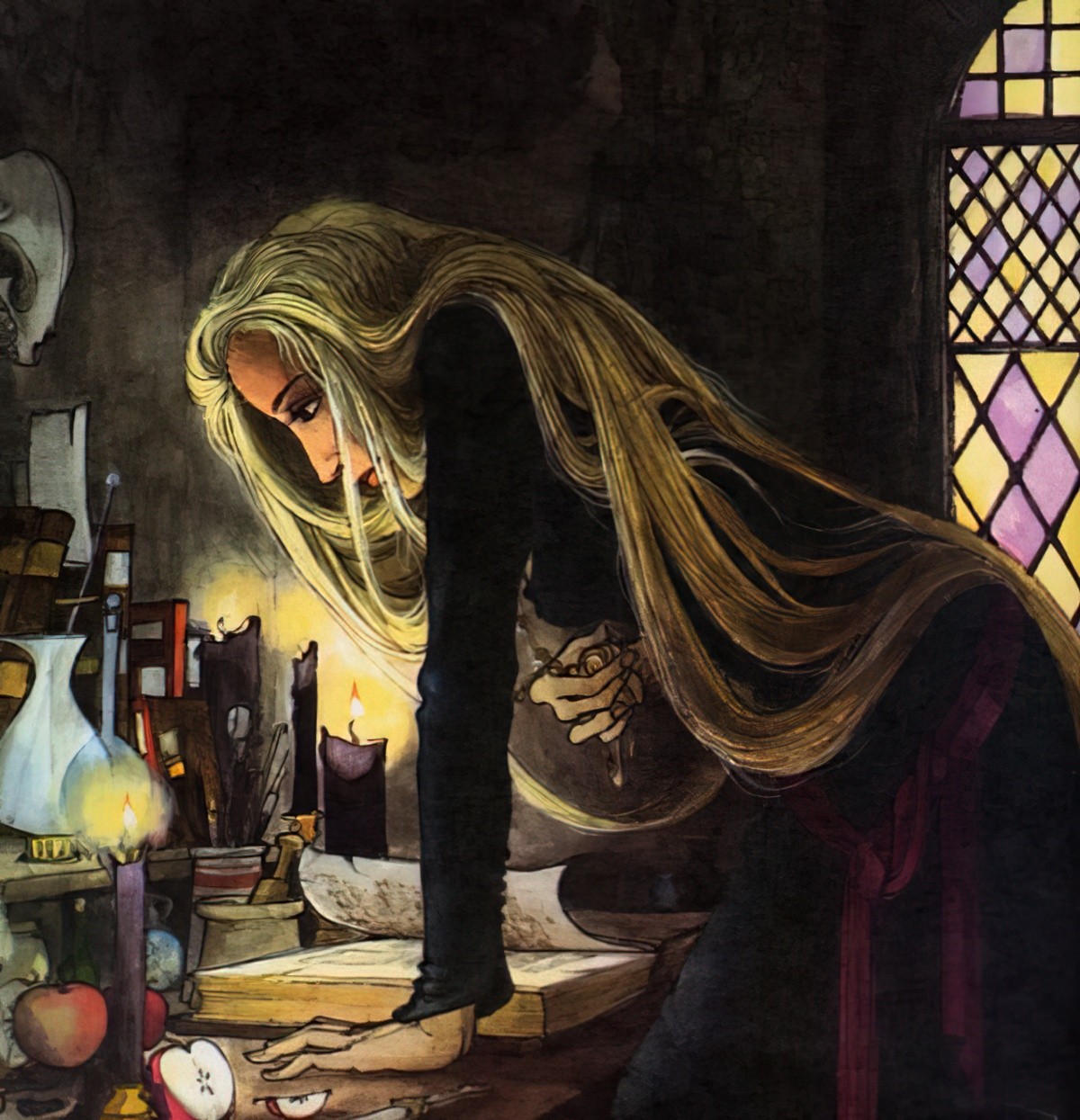

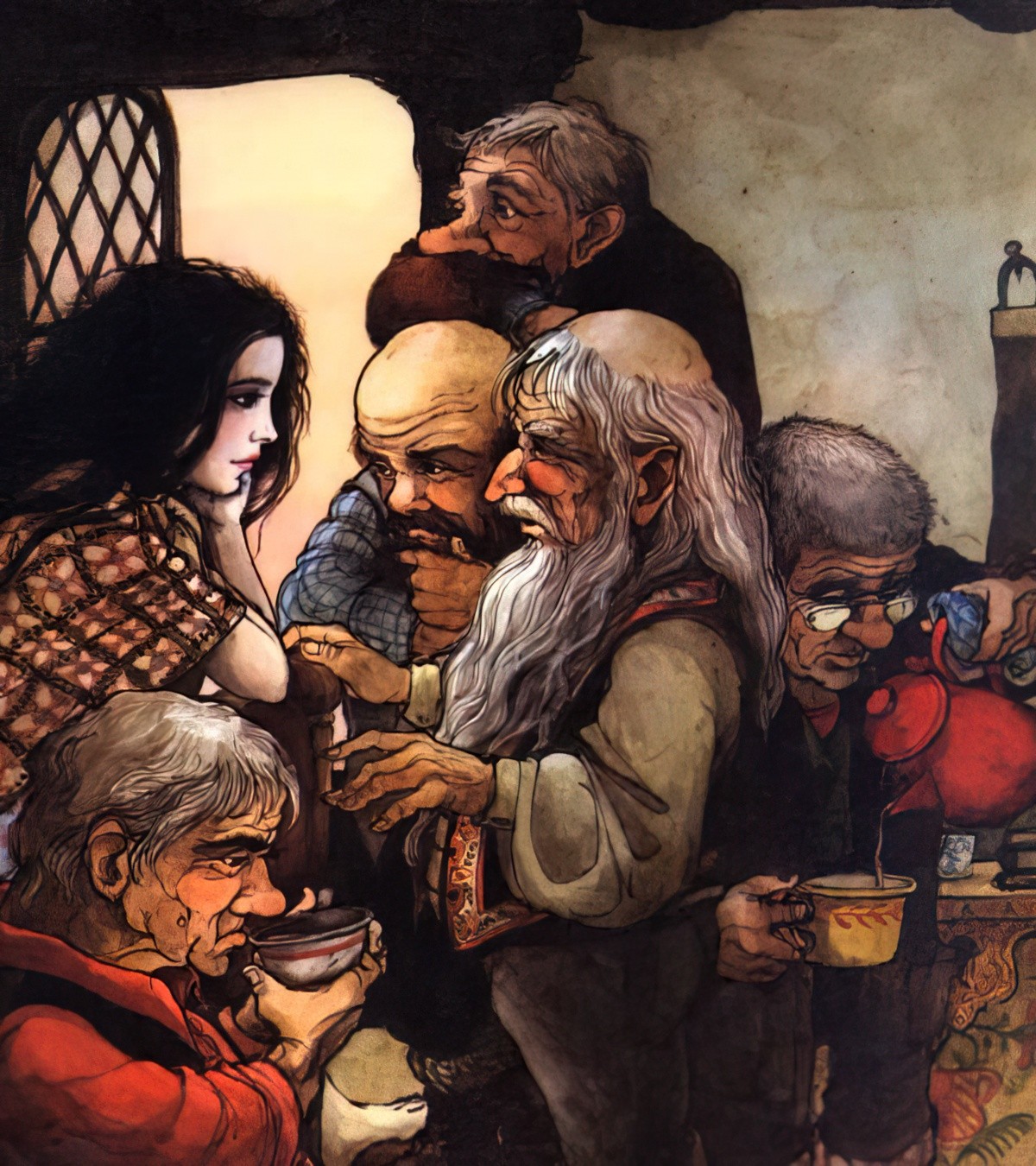

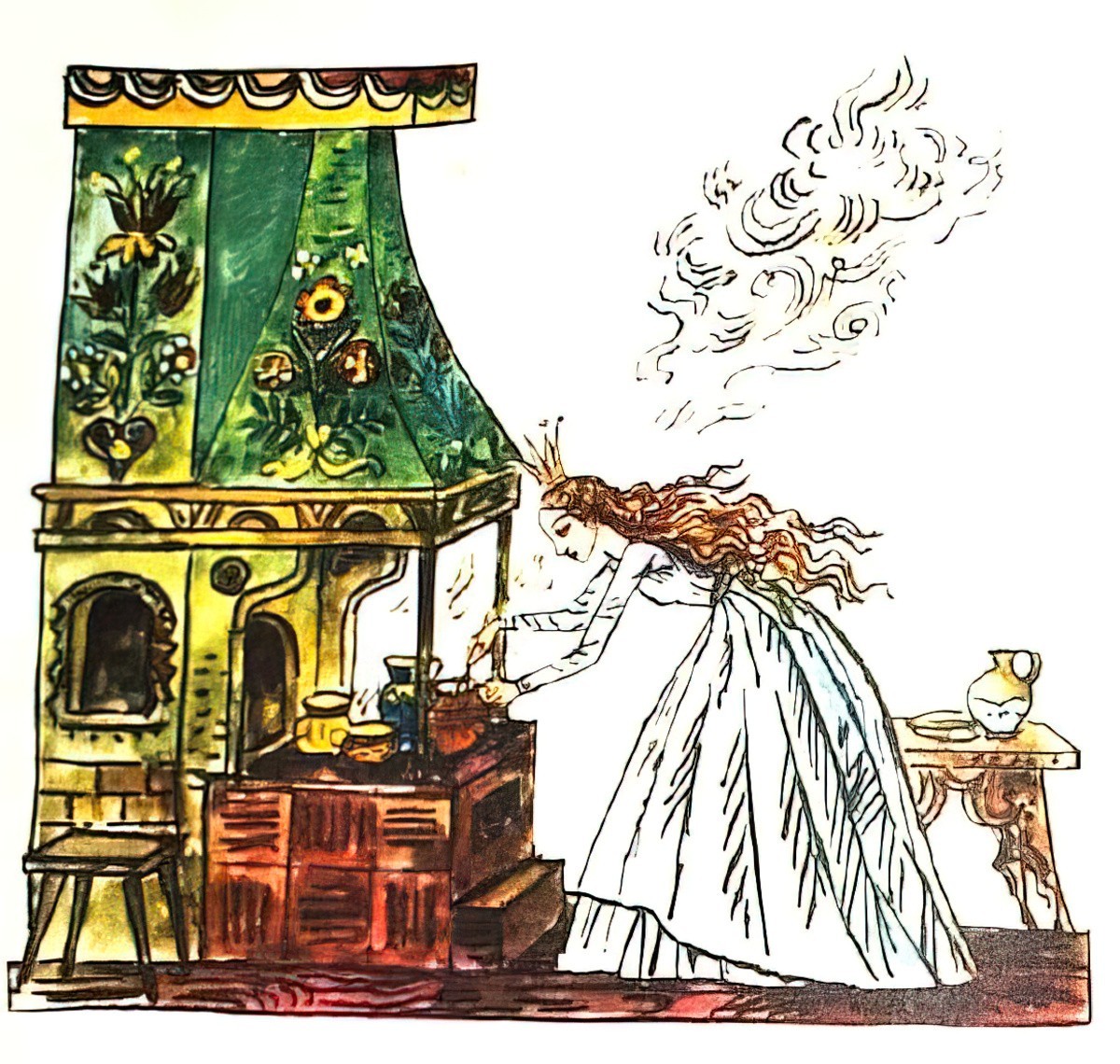

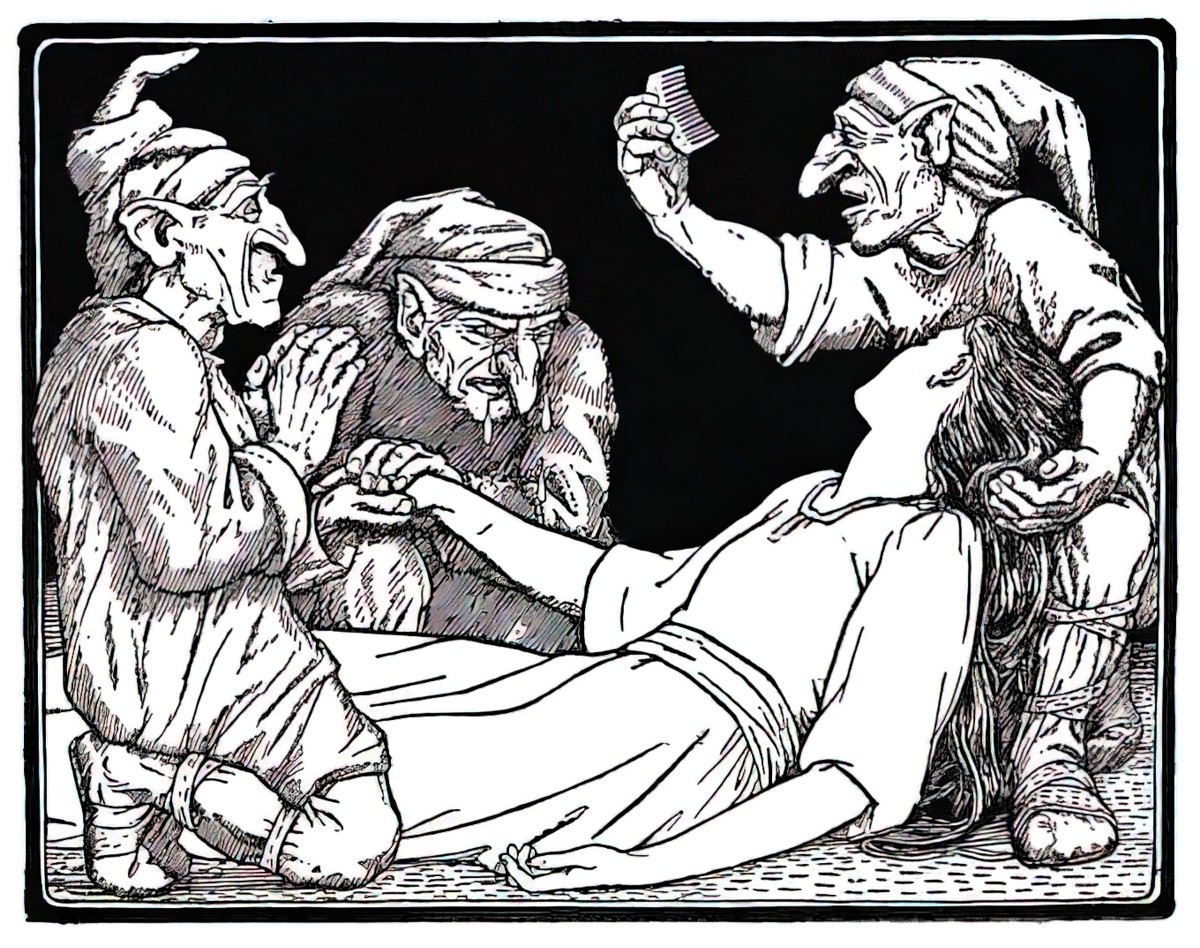

If Jeffers perfectly balances involvement and detachment in the fashion of the original story, and if Human’s pictures move the balance in favour of intensity, Burkert’s pictures move the pictures in the opposite direction. Like Hyman, she creates a new counterpoint. Burkert’s pictures show not a single one of the key moments. Some of them do get close: we do see Snow White’s mother at the window but before she has pricked her finger, for there is no drop of blood, and we do see the Princes look at Snow White in the coffin—but not as he first sees her, only after he has begun to carry off the coffin. In fact, all the pictures in this book depict moments between and around the significant episodes of the plot. We see Snow White after she is left alone in the forest. We see her doing housework for the dwarfs after she has found their house but before the Queen has found her. We see Snow White lying dead after being laced and the Queen in her workroom after the episodes of the laces and the comb but before delivering the apple. The final picture shows a moment after the Queen has died but before the Prince and Snow White are married. Considered separately from the text, these pictures actually tell an entirely different story from the text: they depict a series of ordinary moments in the life of people in the past instead of an exciting sequence of events.

Furthermore, these pictures display no exciting action and none of the intense emotion we find in Hyman. Snow White’s mother sits. Snow White calls the dwarfs to dinner or lies dead. Only the Queen seems to move with any speed, and she always does it with her back to us, so that we regard her action with emotional distance. In reading this book, we move from the fast thrusts forward of the text to lengthy pauses as we respond to pictures of people in repose that are detailed in a way that demands objective analysis, and then back to quick action again; the effect is strong dramatic tension. In fact, it is the interesting contrast between the very objective, detached, distant pictures and the fast action of the plot that makes the detachment acceptable, and it is the detachment that makes this a convincing story of dispassionate justice.

STORY SPECS

Burkert’s Snow White was first published 1972

Won Caldecott Honor in 1973

Published again by Square Fish in 1987

Hyman’s Snow White, written by Paul Heins, was published November 30th 1974 by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

ILLUSTRATE YOUR OWN

If you were to add something to the corpus of illustrated tales out there, how would you adapt your favourite lesser-known fairytale? Which of the key scenes are the most frequently done? Which of the scenes in your own imagination has no one ever seen before?

I do like to read shopping lists which have been left at the bottom of my shopping trolley. Who knew The Wicked Step-mother of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves liked lasagne?

RELATED LINKS

- Buzzfeed has a list of fascinating facts about Disney’s adaptation of Snow White, if you happen to find the Disney version fascinating.

- The magic mirror in the fairy tales has a real-world counterpart in The Talking Mirror of 18th century Bavarian queen Claudia Elisabeth von Reichenstein. You can gaze into this fine looking glass at the Spessart Museum.

- The Arcane Origins of the Tale of Snow White from Daily Grail