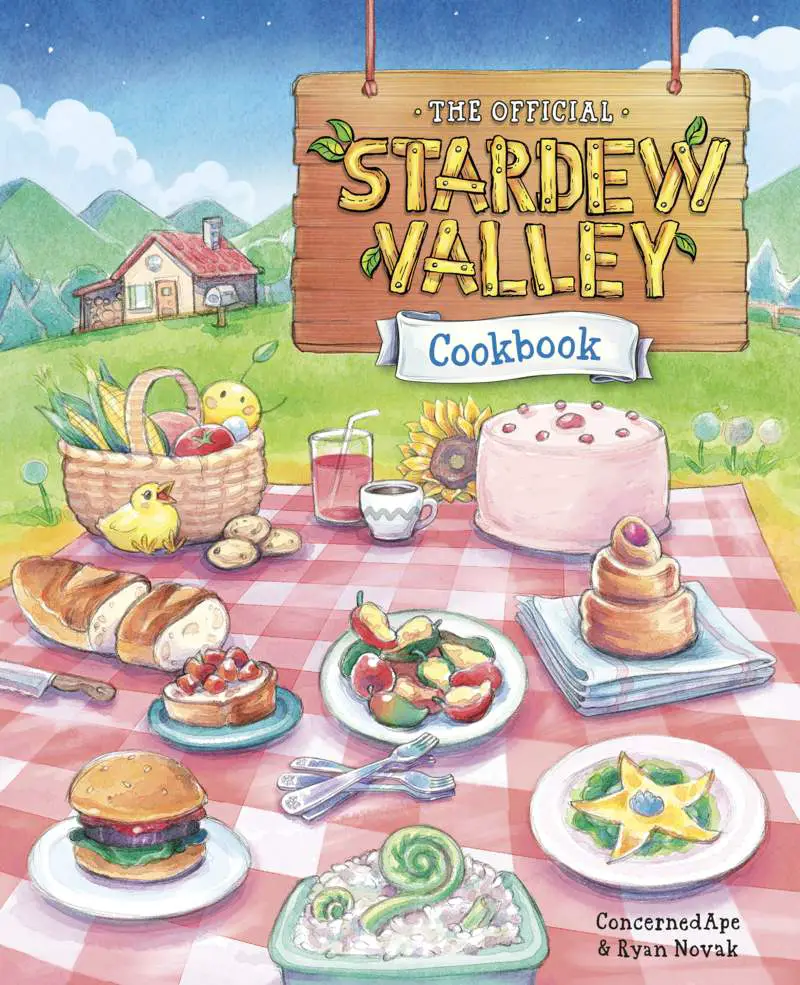

Picnics — literal picnics — play an important role in Western children’s literature. When discussing children’s literature, ‘picnic’ has a different, related meaning.

Perhaps the stand-out example of picnicking in children’s literature is The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Grahame. This utopian setting has been rendered even more memorable because of the beautiful illustrations by various artists over the generations.

The Wind In The Willows includes a great picnic scene and is used on the cover of various editions.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF PICNICS

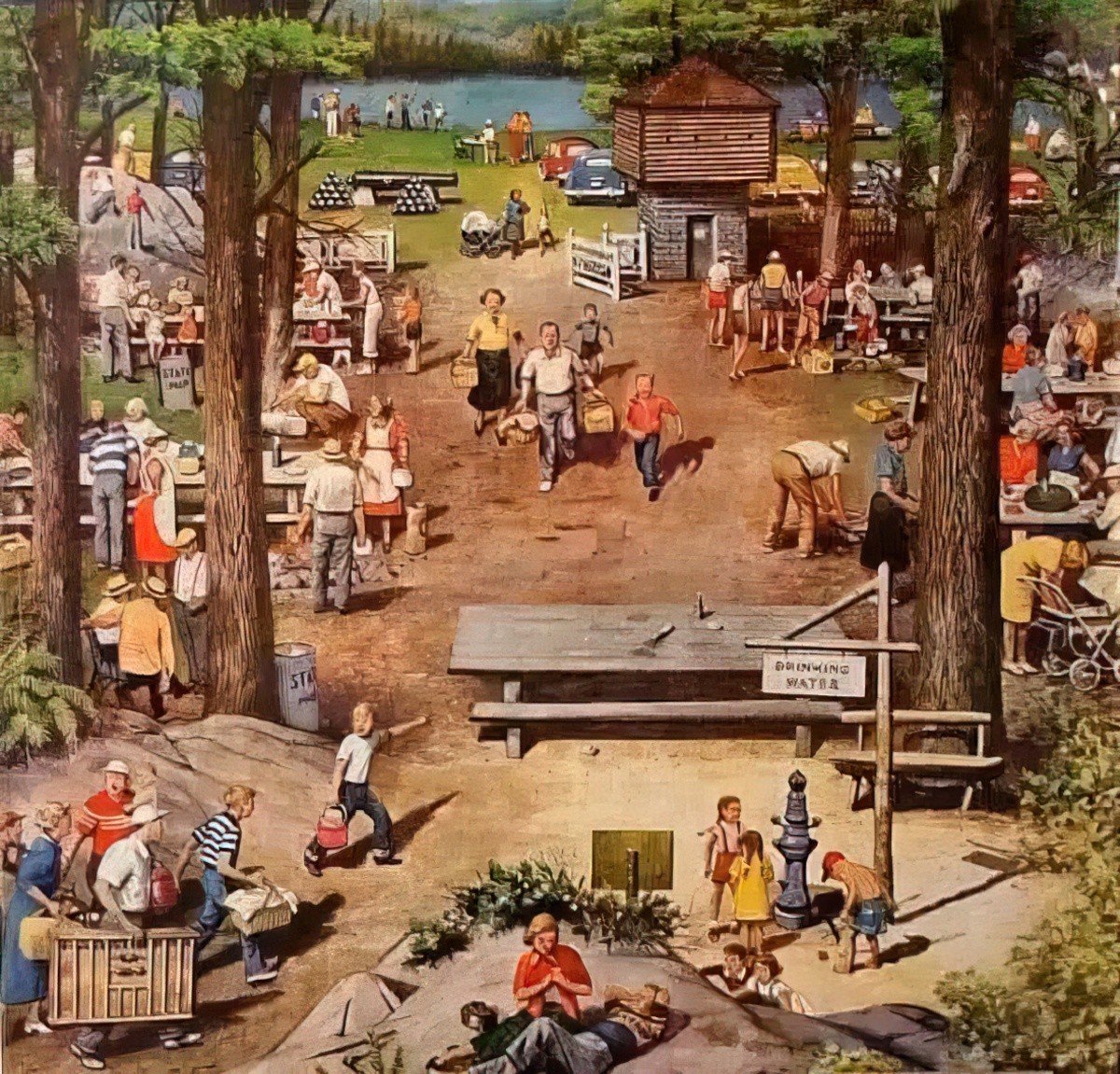

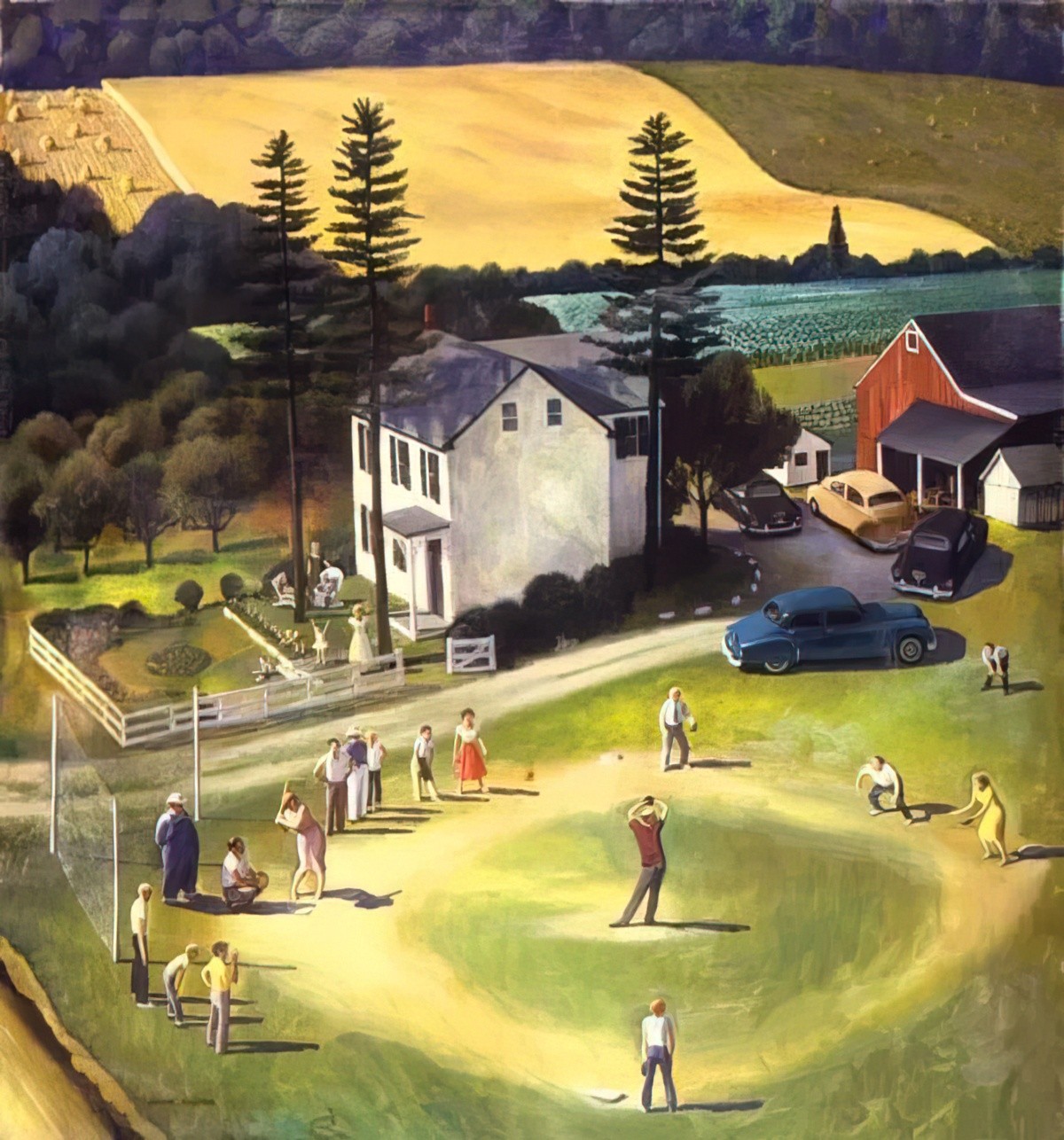

This artwork by Arthur Sarnoff captures the feel of a mid-century village picnic, with the women organising everything and the men carrying the heavy things. Looking at that steeple in the background, I’m reminded of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, in which Call (a cowboy born in the early 1800s) isn’t quite sure what picnics are, exactly, but thinks they have something to do with church.

One of the better picnic scenes of literature comes from Jane Austen’s Emma.

Another is from Charles Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

THE BRITISH PICNIC

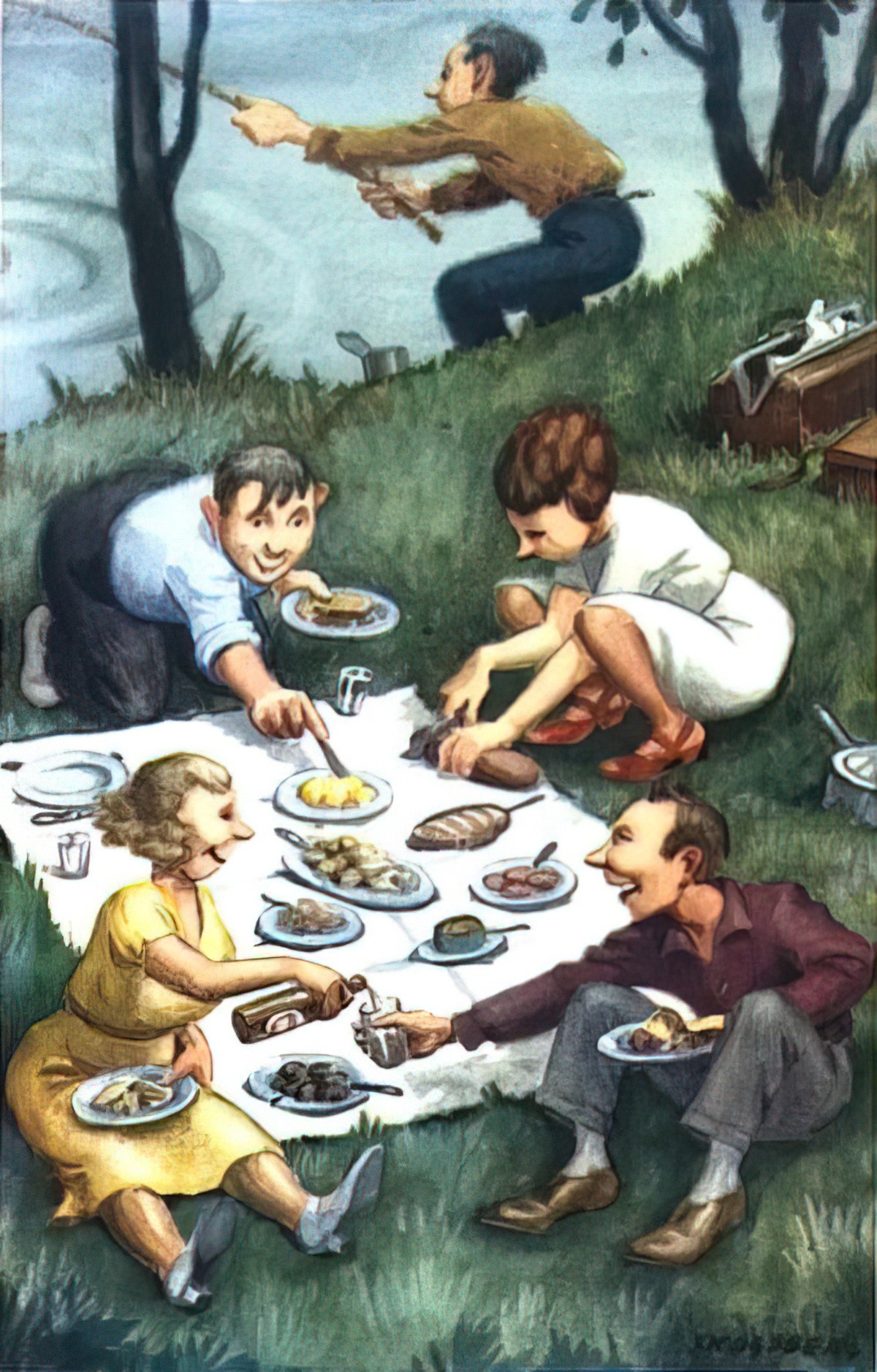

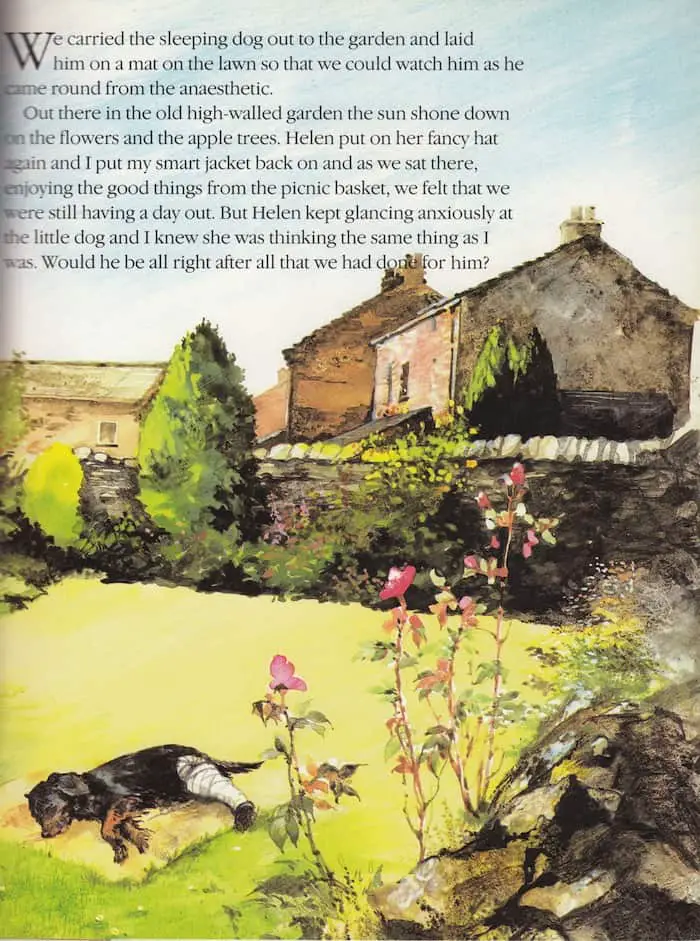

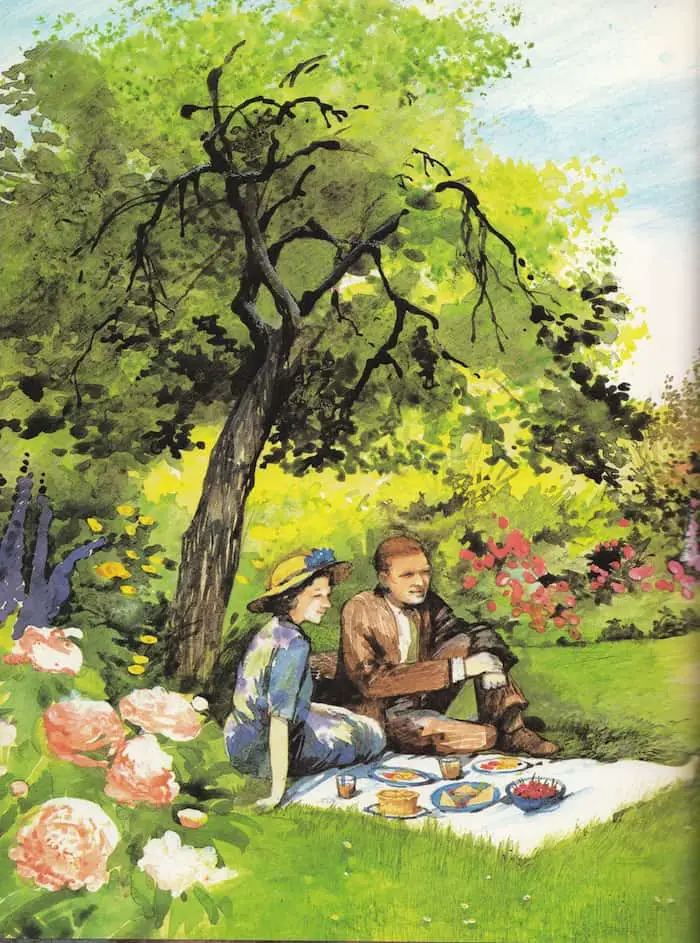

This is a spread from James Herriot’s The Market Square Dog, with illustrations by Ruth Brown.

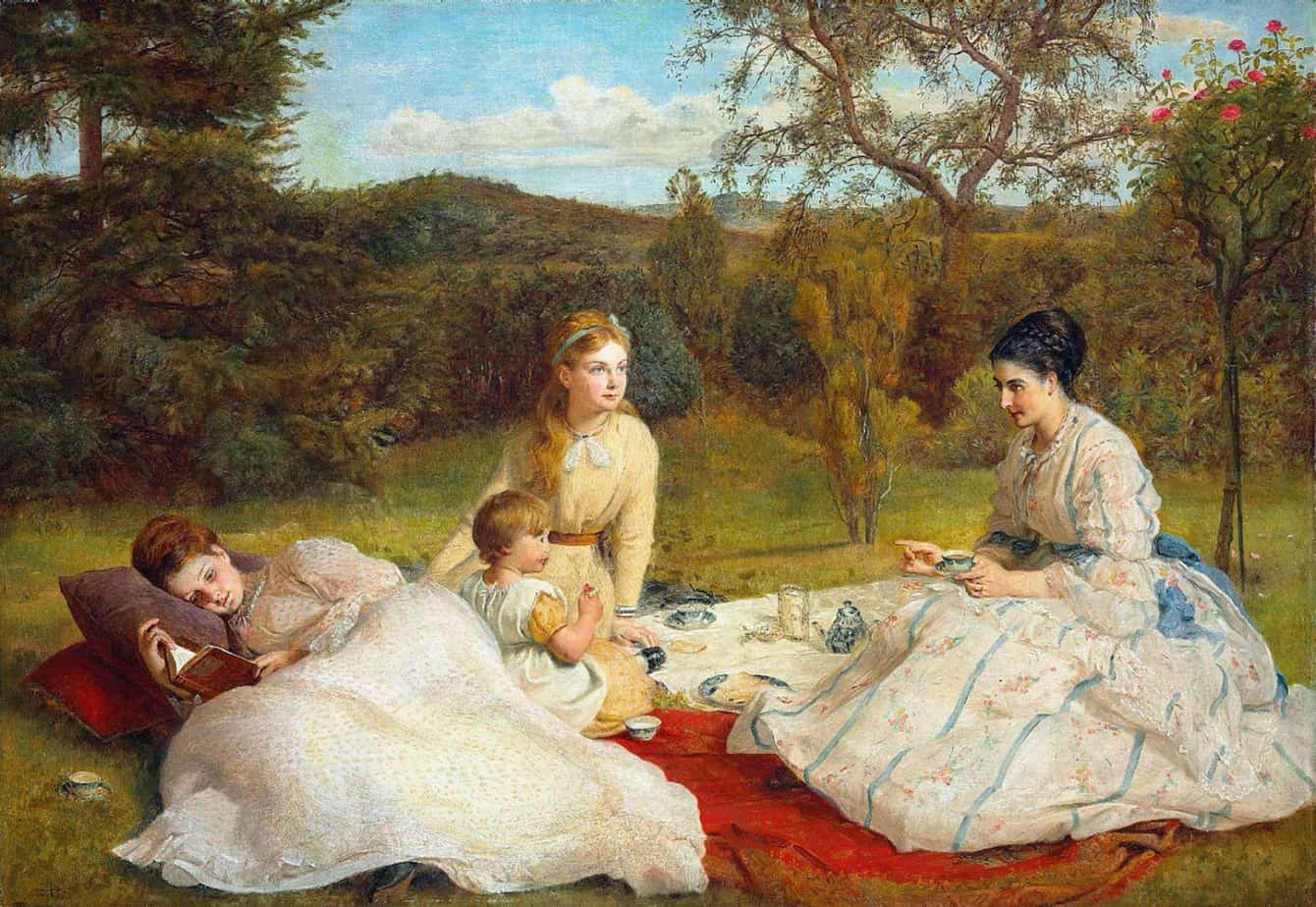

If a family had servants to set it all up, the picnic could be a lavish affair indeed.

THE AMERICAN PICNIC

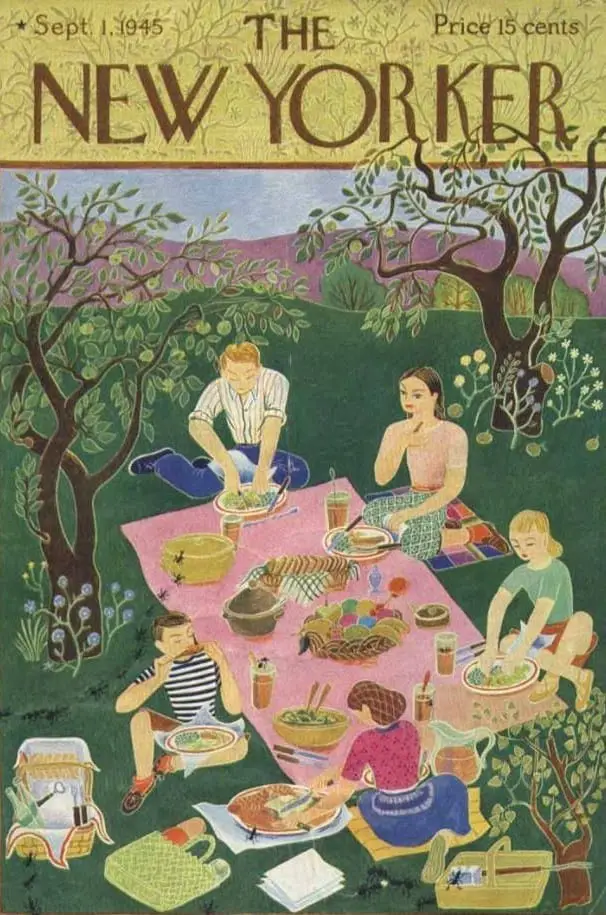

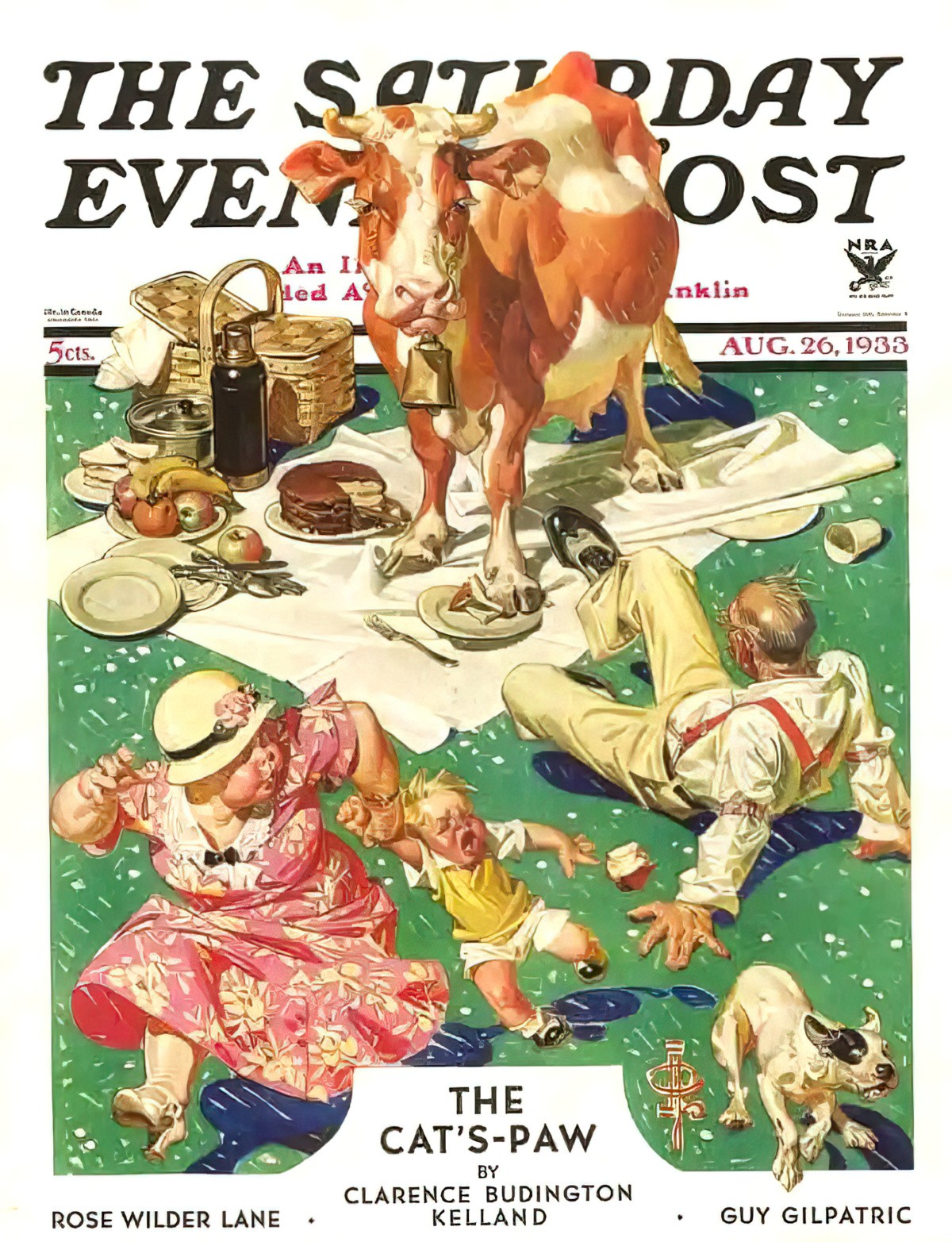

The bird’s eye perspective of Steven Danlos’s cover for the Saturday Evening Post has both a Where’s Wally panoramic feel to it, but is also slightly disconcerting, standing in contrast to all of those picture book picnics, genuinely cosy, in which the eye is down much lower. Who is watching these people? While they’re having a good time they are distracted.

THE AUSTRALIAN PICNIC

Since moving to Australia and I don’t think this country is especially well suited to picnicking. It’s either too hot and dry or your BBQ attracts flies. There are certain times of year and certain specific places where picnics work well. That probably isn’t summer.

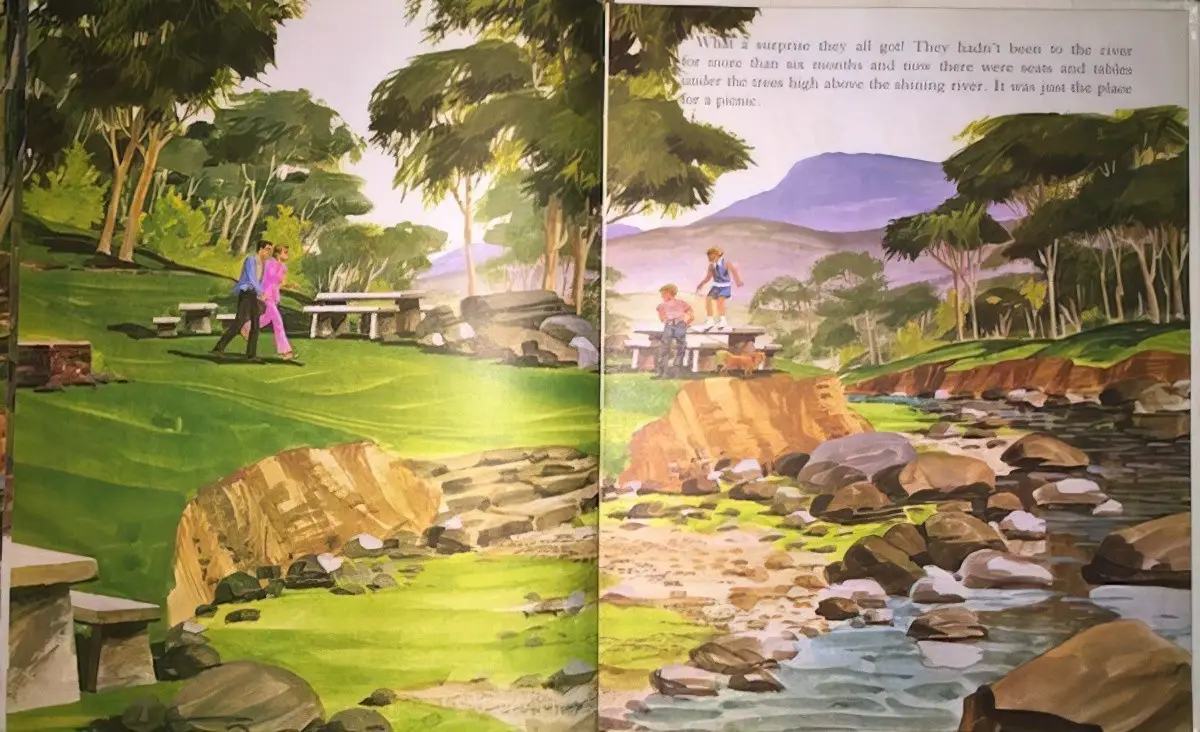

There’s an ‘Australian Golden Book’ — hard to find now, with 1970s images of an English style picnic, but in a realistically depicted Australian setting.

In this story, published 1970, an advertisement-worthy white nuclear family sets off in their brand new yellow station wagon to enjoy a day in the Australian bush.

This is a very typical Australian scene — I believe I see the Blue Mountains in the background.

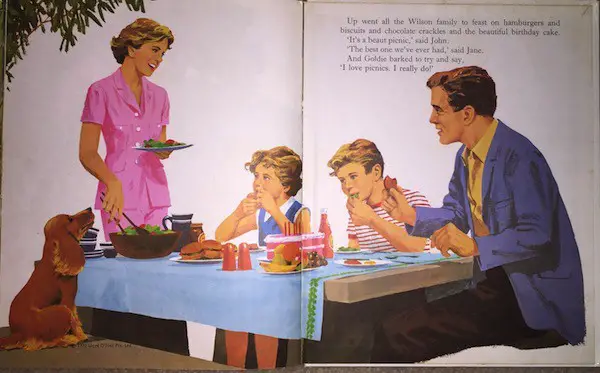

The mother, dressed in an appropriately feminine pink, dishes up as if they are all at home. These days the children would be wearing wide-brimmed hats.

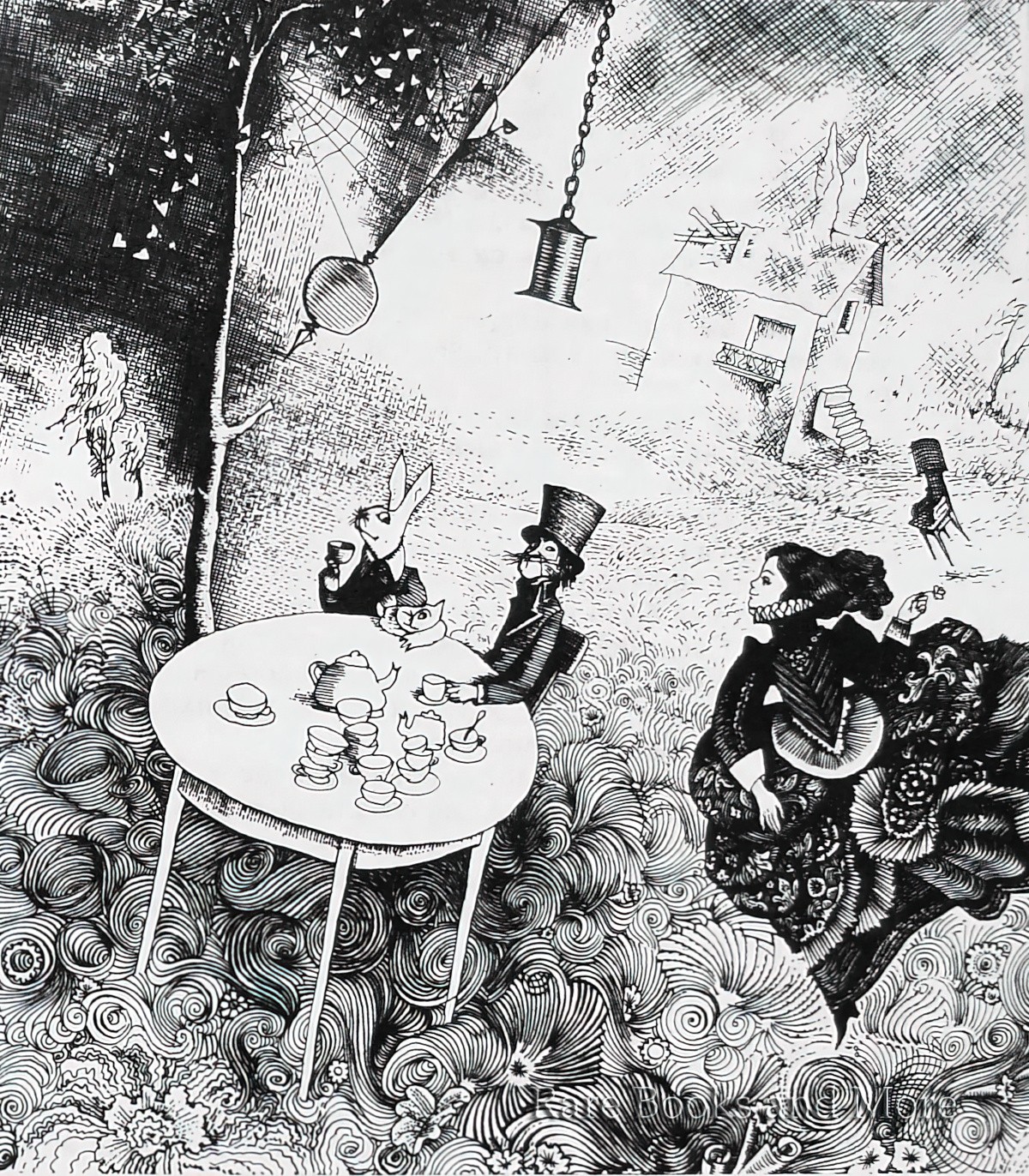

THE CREEPY PICNIC

These goblin markets aren’t picnics per se, but they feature food in the great outdoors. Like clowns, ice cream vans and nursery rhymes, what is childlike and fun can be repurposed for horror. The carnivalesque, after all, is about both fun and horror.

ANOTHER USE FOR THE WORD ‘PICNIC’

When talking about central patterns in children’s stories, the word ‘quest’ is used quite frequently: A character leaves home, goes on a quest, comes back home again.

But Maria Nikolajeva chooses the ‘more prosaic’ term ‘picnic’ over ‘quest’ in reference to children’s literature, in particular:

The fact is that in most quest stories for children…the protagonists, unlike the hero in myth (or a novice during initiation), are liberated from the necessity to suffer the consequences of their actions. What is described is not the real rite of passage, but merely play or, to follow Bakhtin’s notion, carnival.

Further points:

- In the Narnia Chronicles, when the children return to their primary world, ‘the wonderful adventure [in Narnia] has been merely a “time-out”, a picnic.’ Nikolajeva likens these books to a modern computer game, in which the player ‘dies’, but simply plays the game again, consequence free.

- ‘A crucial discussion of any magical there-and-back-again adventures is whether main characters indeed mature through these exercises in liberation, whether they gain knowledge and experience, and draw conclusions: that is, whether these adventures prepare them for the definite step toward adulthood in the future.’

- ‘It is extremely seldom that children’s writers describe the impact of a magical journey as negative, as Garner does in Elidor. Another example is Alison Uttley’s A Traveller in Time, where the protagonist is permanently injured by her involvement with the past, which means that she cannot cope with her real life. […] In adult literature, on the contrary, it is highly probable that daydreaming, the creation of worlds of fancy, leads to a mental disturbance or at least to a total re-evaluation of one’s life. We may recollect, for instance, the reactions of Lemuel Gulliver upon his return from the land of giants or the land of horses.’

- Nikolajeva argues that there is no real difference between time-shift fantasy and secondary world fantasy, nor is there any real difference between fantasy and ‘realistic’ adventure.

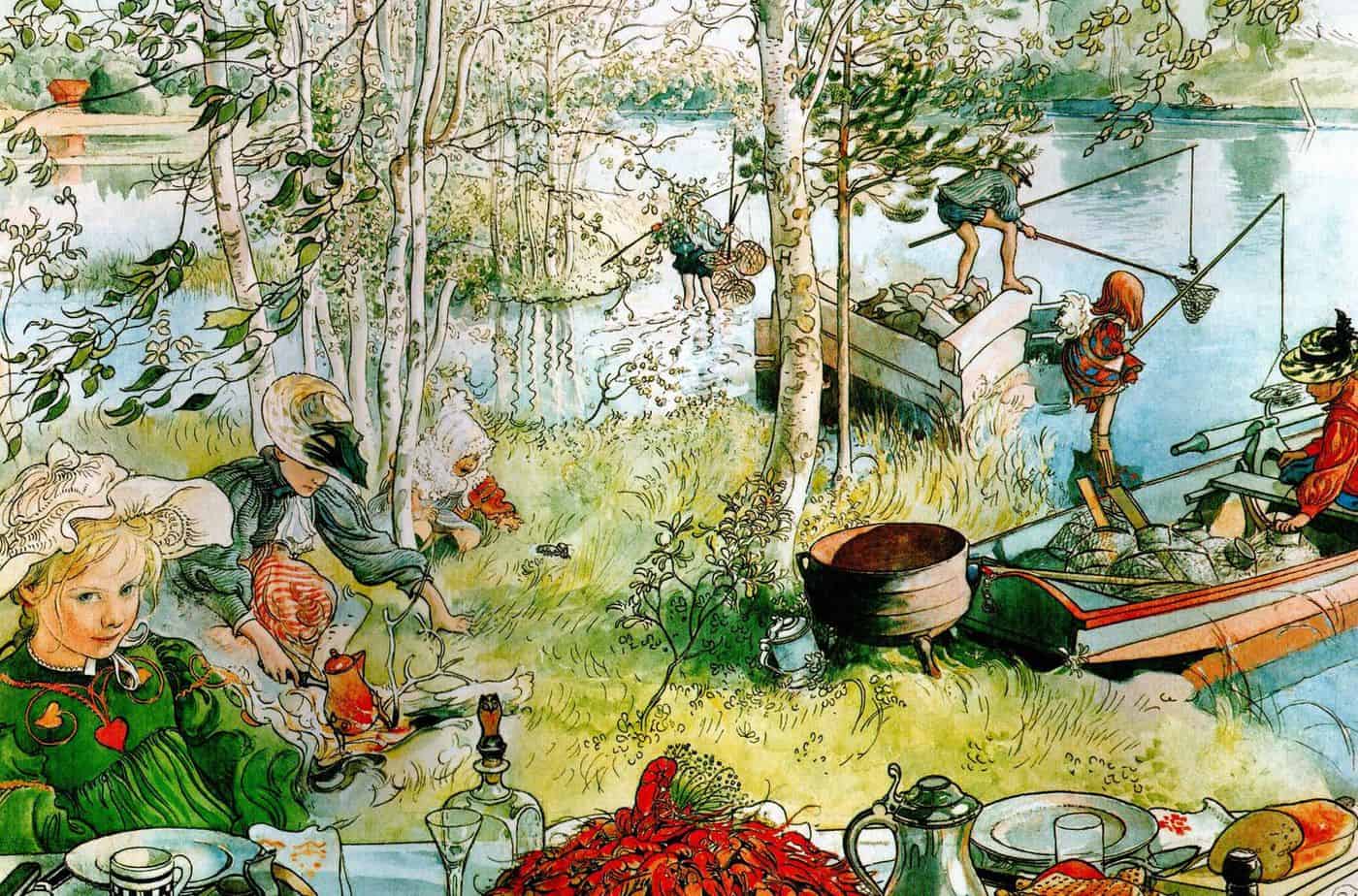

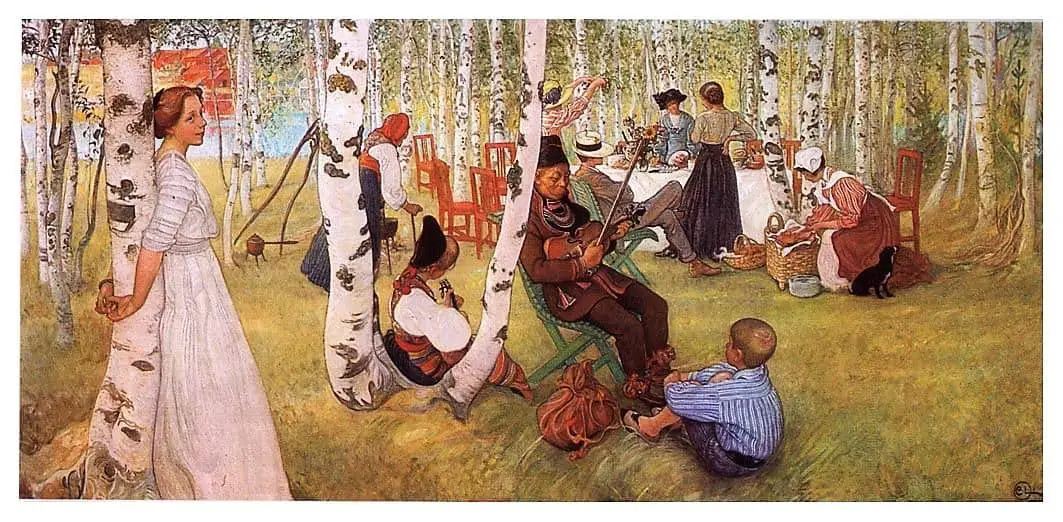

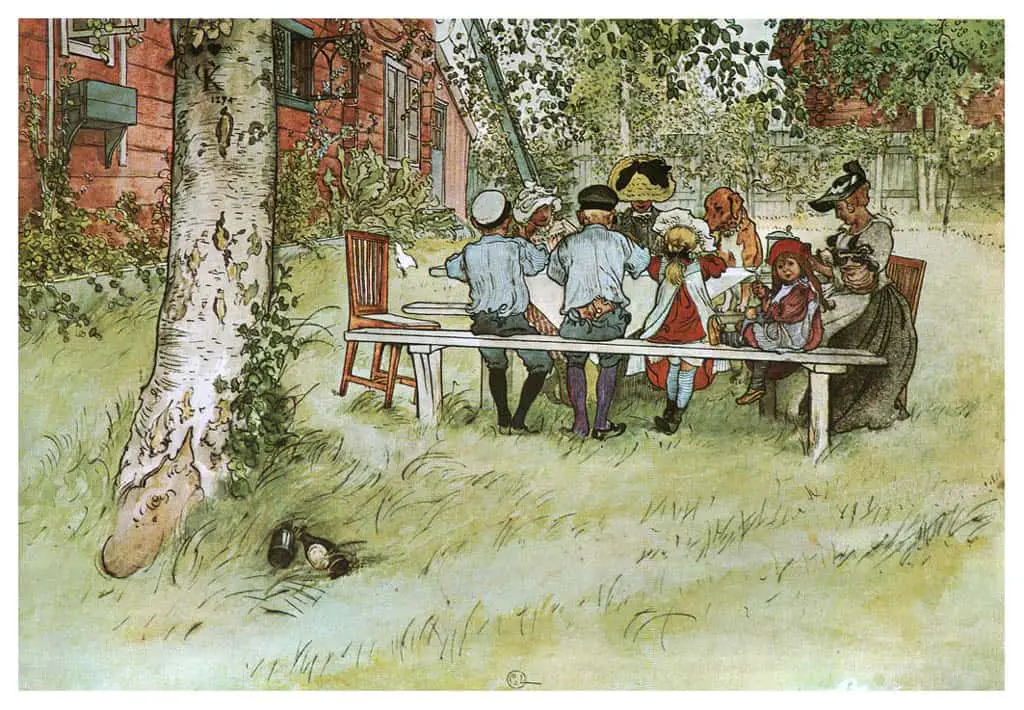

SWEDISH PICNICS

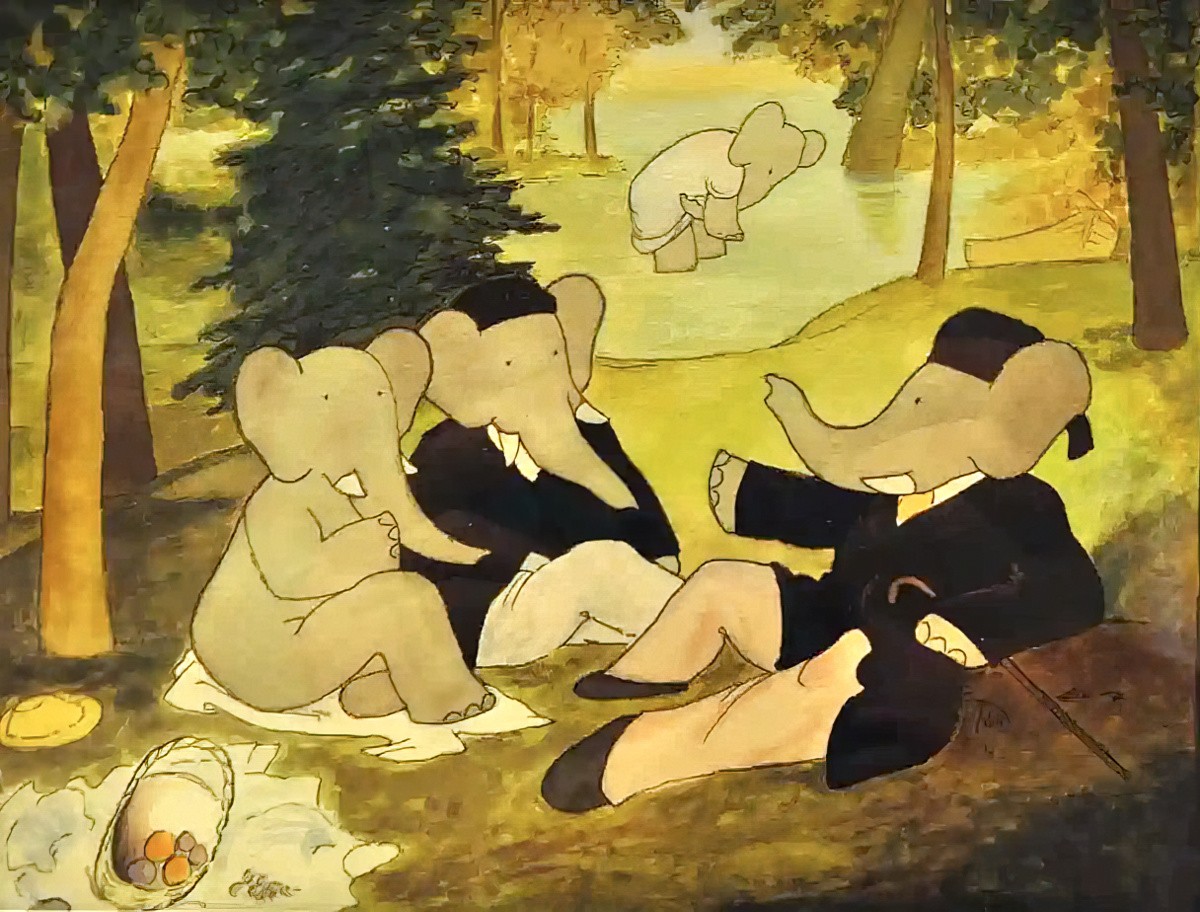

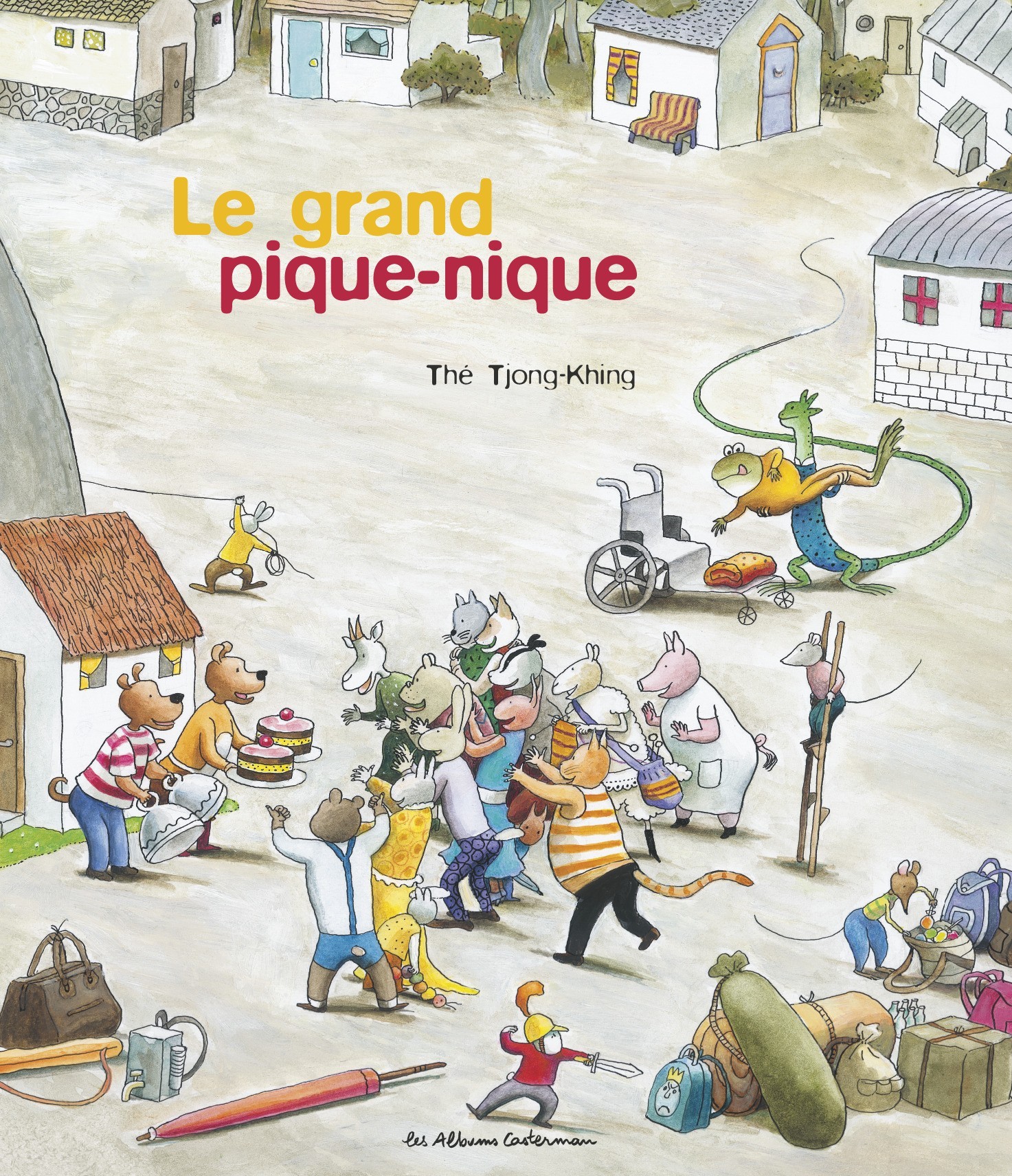

THE EUROPEAN PICNIC

Related Links About Food and Picnics and Children’s Books

Infant and Toddler Books About Picnics

Food and Sex In Children’s Literature

The Bear Books by Jez Alborough feature a boy and his mother who venture into the woods for a picnic.