The Piano (1993) is a lyrical, fairytale film written and directed by Jane Campion, set and filmed in New Zealand near the beginning of white colonisation.

SETTING OF THE PIANO

Like many creative New Zealanders, Campion comes from Wellington. I don’t know why so much creativity comes out of the Wellington region, but I suspect it has something to do with the dramatic landscape and its harsh climate. I don’t dismissively mean that the weather is so terrible that people have nothing else to do but stay inside and make their own fun. I mean, when you immerse yourself in New Zealand’s most outdoors settings, you can occasionally be struck by a sense of awe, and that awe carries over into your work.

The Piano is not filmed in Wellington, but 40 minutes out of Auckland, near the top of New Zealand’s North Island rather than at the bottom. The beach scenes were filmed at Karekare.

A beach setting can be utilised to various effects in storytelling. In The Piano, the dark, misty coastal setting is utilised as a Gothic, liminal space. George falls in love with Ada on the beach. The piano itself is stuck for a time on this otherwordly beach, just as Ada is stuck in the unfathomable situation of being mute but not deaf, caught between the magic of music and human society.

This is the location of the famous piano-on-the-beach scene in The Piano. Still if you look hard enough you can usually find a spot to put a towel down #karekare #NZHellhole pic.twitter.com/AFw8AnjGhI

— The Bushline (@thebushline) January 11, 2021

The Bushline (@thebushline) also points out that Crowded House recorded most of the Together Alone album in a home overlooking Karekare. The opening track is named after the beach:

The 1980s New Zealand painting below captures, for me, the Kiwi tradition of wading into the sea no matter the weather. The ocean just looks cold, doesn’t it?

THE FAIRYTALE SETTING OF THE PIANO

This story makes an overt link to European fairytale with the subplot of the amateur Bluebeard production, performed by the locals as a way to pass the time. The Bluebeard fairytale is not so often collected in fairytales marketed to children, yet forms the ur-plot of many stories for adults.

Ada is clearly a Little Mermaid archetype. Music is a force which communicates (eventually) to Alisdair as if by magic. Music as magical communication is a popular fairytale trope, where it can be so powerful it takes you over and controls your actions.

There’s the civilisation on the edge of a forest, and the forest is specifically New Zealand (with abundant ferns and native New Zealand bird calls) but still functions as the dark human psyche. Terrible things happen in this forest, which is also a playground for children, where they explore ideas beyond their years.

As an aside, I feel downcast after watching the forested scenes in a film set over a century ago. Eighty per cent of Aotearoa was once forested. But by the year 2000, we had cut and burnt nearly three-quarters of it. In contrast, Japan did the sensible thing and protected two-thirds of its forested land, despite housing 25 times the New Zealand population. To make matters worse, this was known to environmentally aware New Zealanders back in the 1970s, when Aotearoa was cutting down its own forest to export to Japan, who were sensible enough to protect their own.

Fairytales such as Rumpelstiltskin are likewise about young women with childbearing duties who find themselves caught between the avarice and sexual appetites of a community of men (in Rumpelstiltskin it’s the father, the king and the dwarf).

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE PIANO

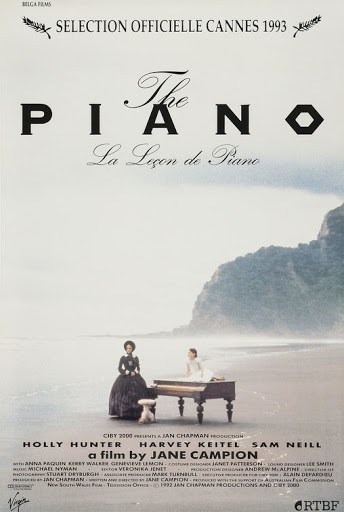

PARATEXT

In the mid-19th century, a mute woman is sent to New Zealand along with her young daughter and prized piano for an arranged marriage to a wealthy landowner, but is soon lusted after by a local worker on the plantation.

Synopsis

When The Piano was released in my home country of New Zealand, every demographic rushed to see it. If people knew of Campion, it was probably for An Angel At My Table (1990), about New Zealand’s literary great Janet Frame. We watched that film in English literature class, and it appealed to the literary set. The Piano was widely anticipated. This predated Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings franchise, and it was rare to see a film shot in New Zealand, foregrounding our magnificent landscape. We were hungry to see our own landscape depicted on the big screen. We got the native bird calls. But I doubt people expected it to focus on the mud and the mist.

A family of ultra conservative American immigrant friends went to see The Piano one evening at the cinema. Back in 1993 you’d go to a film without knowing much about it. They didn’t last the distance, and nor did other families I knew. They proclaimed it ‘terrible’. A ridiculous movie, not worth talking about. They never told me what, exactly, had offended them so much, and I knew better than to ask.

Frankly, Roger Ebert didn’t help.

That’s from the 1993 trailer, which no one would’ve seen anyway, unless they’d recently been to the movies, proving themselves a bit of a movie buff.

The description of The Piano as an ‘enchanting love story’ reminds me of the mis-marketing of the film adaptation to Brokeback Mountain, which annoys the hell out of Annie Proulx, who went out of her way to write a story about so clearly about hate, ie. toxic homophobia. In contrast, unless I missed it, Jane Campion hasn’t announce her disappointment about any ‘love story’ description of The Piano.

The marketing materials around this film’s release weren’t giving much away, and people took their families thinking it’d be a nice musical piece. They probably expected to hear beautiful piano music scored by Michael Nyman, to tear up at a beautiful love story and without being conscious of it, they probably expected to see a glorification of European settlement. Well, they got the piano soundtrack. I have the album, and it’s not one to put on if your nerves are jangled. It’s about as calming as the Red Dead Redemption soundtrack.

When commissioning the music, Campion asked Nyman for the ‘smallest number of notes in the shortest space’. The music has to sound like it comes from Ada, who hasn’t the same musical background as a 20th century composer. Nyman also looked at Holly Hunter playing the piano and tailored the soundtrack to her style. Sometimes creativity is at its best when the creator works within externally composed limits, and Nyman’s Piano soundtrack is an excellent example of that.

Later, when Anna Paquin became the youngest person to win Best Supporting Actress, and very charmingly accepted her prize on stage, The Piano became almost better known for that heartwarming moment.

Discussion revolved around how much acting Paquin had actually done. It seemed to the non-acting audience that she’d simply been her childlike self. People forgot that Paquin was required to speak in an accent that was not her own. (Her natural New Zealand accent of the time reveals itself in her acceptance speech.)

You can’t just tell actors, especially young ones, to ‘act happy’ and expect them to do it. They must in some essential way be happy.

Roger Ebert

More than a decade passed before I saw the actual film myself. It’s a hard film to ‘love’ but I was fully immersed in it.

SYNOPSIS

The spine of the plot is simple, in line with its clear fairytale ur-stories.

Once upon a time, a mute woman and her daughter arrived from Scotland to be the new family of a white settler in 1800s New Zealand. In a secret deal with the new husband, another man buys the woman’s piano in exchange for a plot of land. He then coerces the wife into sexual favours in exchange for her beloved piano back. The new husband finds out, and in retaliation, chops off his wife’s finger. However, the two men are friends, and they agree between them that the wife can go away with the man she seems to have fallen in love with. The wife tries to kill herself but decides at the moment of crisis to choose life. In their new, sunny home, the new husband makes her a prosthetic finger. She has her piano back and can now play it again.

Do they live happily ever after? That’s for the audience to decide.

SHORTCOMING

Ada is our main viewpoint character, though we also see the story world through the eyes of both men at various times. This story does not have a clear ‘main character’, as such. It works like Brokeback Mountain and many other Annie Proulx short stories — it is the story of a small community rather than of an individual’s journey.

Ada is mute, which is an interesting storytelling decision for several reasons. First, there’s the clear link to The Little Mermaid who, like this character, exists in a liminal space between land and sea, between the human social world and a world of her own. (Ada’s link to the ocean is used at the climax, later.)

The decision not to give your main female character a voice is a little tricky to pull off when feminist-minded storytellers (myself included) are keenly aware of the stats around women and lack of speaking opportunities in film, resulting in a form of symbolic annihilation. That said, to render a woman mute is a feminist statement in its own right — a visceral depiction of the lack of female autonomy.

Ada has replaced speaking in words with speaking via music. This naturally foregrounds Michael Nyman’s soundtrack. The music is a character in its own right. The audience is now also required to do a close-reading on this film using other senses. Especially when viewed on the big screen, this film is more about the sensory experiences without the distraction of words.

Ada is presented as childlike. Holly Hunter’s small frame helps with that, and this, too, becomes important at the climax. More generally it means she’s vulnerable among these strong, violent, axe-wielding men.

DESIRE

We don’t know if Ada wanted to come to New Zealand but historically literate audiences know that women had limited autonomy, and was likely sent after no genuine choice. She’s arrived in this new world with her only daughter and most prized possession: her piano. She wants to keep playing her piano. Any romance is for Ada secondary, which is bad luck for her, because it’s now her main job.

OPPONENT

ALISDAIR

Ada’s first romantic opponent is her new husband, Alisdair Stewart, played by Sam Neill, who suspects her of being ‘stunted’ and intellectually impaired as well as mute. Despite this, he expects sex.

GEORGE

Ada’s second romantic opponent is George Baines, played by Harvey Keitel, who contrasts with Alisdair. Whereas Alisdair is a buttoned-up WASP, with typically colonial attitudes, and conservative about sex, George’s crudely inked Mataora moko shows he has been somewhat accepted by local Māori. His views are far more liberal than those of the white, Protestant immigrants, and he is also more in touch with his own emotions, as well as with the land. Campion shows audiences that the Māori people are yet to experience the full force of colonisation; hence the takatāpuitanga character.

George Baines strikes a deal with Ada: After buying her piano from Alisdair, he agrees to give it back, key by key, for increasingly intimate sexual favours.

FLORA

Ada’s other opponent is her young daughter, Flora, played by Anna Paquin. When we first meet Flora she is roller skating down the hallway of a house, next she is sleeping angelically in bed.

This introductory juxtaposition shows us that Flora is an authentically childlike child, but she’s been thrust into the unusual position of functioning as her mother’s mouthpiece ever since she could speak herself. (An experience also shared by many children of immigrants.)

Away from her homeland, Flora is now forced prematurely into a violent adult world she cannot possibly understand, but she’s seen just enough to think she does. So she acts as her mother’s keeper.

When Flora makes the decision to ‘tell on’ her mother, she is subsequently traumatised by Alisdair, who chops off her mother’s finger in front of her. He instructs Flora to deliver the dismembered finger to the mother’s lover. Notice how crossroad symbolism is utilised in the moral decision — an aerial shot shows Flora first taking the path to see George, then she turns back and takes the path to her violent step-father.

The casting of childlike Anna Paquin was perfect. We can’t judge Flora harshly because Campion amplified the childlike innocence of Flora by showing her playing imaginary (sexualised) games with the trees, and also by showing her singing, skipping and turning cartwheels.

Another vital scene: Flora unwittingly gossips about her own mother to the neighbourhood busybody and her adult (but naive) daughter. “That’s a very strong opinion,” says Aunt Morag, a Mrs Lynde archetype, who has the potential to be either an ally or an opponent to Ada. “I know,” replies little Flora, thinking herself one of the grown-ups, “It’s unholy.”

At the time, the audience will be amused by this conversation for its earnest precocity. (Aunt Morag and her daughter are also comedic archetypes — gossiping village wives.) But this scene is a storytelling example of delayed decoding: Only in hindsight do we understand its significance. Despite their very close mother-daughter relationship, this was Campion showing us that Flora was always capable of selling her mother out.

PLAN

This plan is driven by an opponent rather than the ‘main character‘ (Ada). Two two men are complicit in taking Ada’s piano away from her. George’s motivations are clear. But why does Alisdair not want his new wife to have her piano? His motivations are more mercenary. He is a white man who’s main motivation in New Zealand is in securing as much land as he can, which is going for ‘a reasonable price’. Everything else is secondary. Alisdair is the face of the white colonisation of 1800s New Zealand. For these settlers, emotion did not come into it, unless we count ‘greed’ as an emotion.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The Piano constantly juxtaposes tenderness against violence, and also combines the two.

The subplot wraps up first. Its climax is the comedic staging of the Bluebeard play. Male Māori members of the audience misunderstand the scenario, thinking that the man who plays Bluebeard on stage is really about to cause harm to the silhouetted victim behind the sheet. They ambush the stage, coming to her rescue, and ruin the ending. This climax is darkly humorous, and in hindsight, foreshadows the real violence yet to happen off stage. But when it happens in private, there’s no one to come to the woman’s rescue.

The relationship between Ada and Alisdair culminates in the dismembering. You’d think this scene would resonate the most, but I had completely forgotten this part in between viewings. Had I deliberately wiped it from memory?

But Ada’s struggle culminates in her suicide plan which ultimately fails. Now we realise another storytelling reason for her smallness. The plan wouldn’t have worked so well had she been a large person.

ANAGNORISIS

This is where the concept of ‘main character’ is tricky for a story such as this, which is about violence in a small community rather than about an individual, though Ada is positioned as one of the more empathetic characters. It’s Alisdair Stewart who has the revelation. He expresses this revelation to another man rather than to Ada herself, demonstrating his overall disrespect for women has not changed — the ownership of women is something to be sorted out between men, not between a man and a woman as equals.

What Alisdair has realised: Ada has been communicating with him all along, though not in words. He has been listening for the wrong thing.

Ada’s anagnorisis happens in the sea. Once faced with drowning, she struggles for her life. The audience realises everyone in the boat has jumped in to save her, and we see that her life is worth something to the new community after all. The self-revelation that happens under water is an age old trope, also used in the Bible and in Christian ritual. When Ada emerges from the water, she has chosen life over death. She is reborn.

NEW SITUATION

The men agree between them that Ada can go away with George. We are shown a veranda scene which suggests Ada and George will be happy together.

Ada and Flora now live with George in a nice house in a sunny location. George shows tender loving care by making a prosthetic forefinger for Ada so she can continue to play her piano.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The sex between George and Ada starts out as coercive control, and arguably does not stop being coercive, even after the damaged Ada ‘falls in love’ with George. When a ‘partnership’ starts out as extortion, can it ever turn into ‘love’?

The Piano is commonly considered a love story. But by popular definition, a love story is about two (or more) humans who fall in love with each other. This narrative is much more about a woman’s love for music. More resonant to me, which stays with me between between spaced-apart viewings: Love expressed as hate. This story reminds us that the opposite of love is not hate; they can be one and the same. (The opposite of love is indifference.) The Piano is less about love, and more about immigrant women’s role as sex servant and her obligation to provide others with more general aesthetic pleasures.

RESONANCE

The subject matter of The Piano is less shocking than it was back in the mid 1990s. Audiences still see disproportionately little of full male nudity, especially when measured against the vast expanses of female flesh on screen.

[Campion’s] insistence on a stubbornly female gaze in her work did not translate into big box office returns.

The Guardian

I wonder how much of the modern viewing audience does not code this ending as a happy one, but instead as a pyrrhic victory. We see a happy, relaxed and flirtatious scene between Ada and George, who has demonstrated kindness by making her a metallic, steampunk finger so she can keep playing her piano. Like any feminist story which avoids didacticism, it’s up to the audience to see the problems Ada still faces.

Because how damaged does a young woman have to be, how abused, before she thinks the man who extorts sexual favours out of her by withholding her one and only tool of communication is her best option?

For a very modern corollary to the abused woman who runs from an abuser only to find another abuser see the case of Carol Baskin, depicted in the widely watched crime documentary series of 2020, Tiger King. Other, adjacent commentators have made a much better job of evoking audience empathy for this woman, namely the makers of the Real Crime Profile. In their two part series dissecting Tiger King (episodes 249 and 250), Laura Richards’ read of Carol Baskin is more empathetic than that of the Netflix documentarians. Baskin tells (some of) her own backstory while chuckling. The impact of one coercively controlling relationship after another remains unexamined (across the series, not just in the story of Baskin).

My read of fictional Ada is similar to Laura Richards’ read on the real Carol Baskin. The Piano is a masterwork and deserves every accolade. The film trailer was updated on the film’s 25th anniversary release, and no longer contains the description of ‘love story’, instead emphasising the erotic, and also the violence of the axe.

I have nothing in common with ultra conservative audiences who were shocked and horrified at the content of The Piano back in 1993, reviling its very existence. But my inner Annie Proulx remains irritated that The Piano was ever considered a love story. Thanks in large part to activists like Laura Richards, we now have better descriptors. The Piano is a story about coercive control.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Sam Neill played another patriarchal character a few years earlier in Dead Calm, alongside another much younger wife, played by Nicole Kidman. Campion critiques the patriarchal views of Alisdair, but Dead Calm does not encourage any such reading.

I’ve also taken a close look at a film where Holly Hunter does use her very Southern American voice, Thirteen, from 2003, which likewise delves into the relationship between a mother and her daughter, and how the ‘sins of the mother’ have their outworking in the fortune of the daughter.