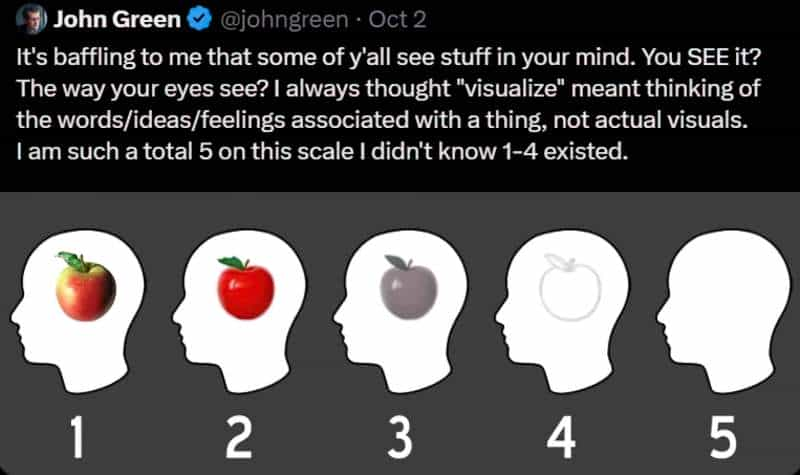

When reading a book, do you ‘see’ scenery in your imagination? If so, you are a phantasic person. Most people have minds which do this, which makes you one of the majority.

Australia’s ABC has an All In The Mind podcast about aphantasia: “The Mind’s Eye“.

If you’d like to know where you might sit on the hyperphantasic- phantasic- aphantasic spectrum, there’s an online test you can take: The Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ). “Discover the vividness of your mind’s eye”, it says.

This quiz is at the Aphantasia Network, so one of the more reliable ones. However, it is difficult to know where to place mental images on a linear chart without having access to other people’s minds. I had a little difficulty with that.

I wasn’t surprised to learn that I am ‘probably phantasic’. (Most of us are.)

However, phantasia is a spectrum. Imagine a beach. Some of you will see a very general image of a beach — more like a painting by a tonalist painter than a detailed photograph.

Others see a detailed photograph, down to the shape of height of the waves, the people, their expressions, their clothing, the colour of their towel.

Some phantasics are able to retain the image in their head for as long as they like. For others, it’s more like a flicker: Try and hold it, the image is gone.

APHANTASIA

Aphantasics don’t typically realise they are aphantasic until learning the word and concept, believing the phrase ‘mind’s eye’ to work like many other metaphors: not a real experience. You may know Shakespeare uses the phrase in Hamlet, but the concept of the mind’s eye dates back as far as Chaucer:

“It were with thilke eyen of his mynde, With whiche men seen, after that they been blynde.”

The Man of Law’s Tale (c. 1390)

Shakespeare wasn’t the first to use the ‘eye’ as a proxy for what we imagine. We know ‘mind’s eye’ was used in 1577 by a French diplomat and reformer called Hubert Languet, who used the phrase in a letter.

Aphantasics may also assume a phrase like ‘counting sheep’ (to fall asleep) is also a metaphor, without realising that other people are seeing sheep jumping over fences.

Aphantasia is not trauma related or anything like that. It’s simply how some brains are wired.

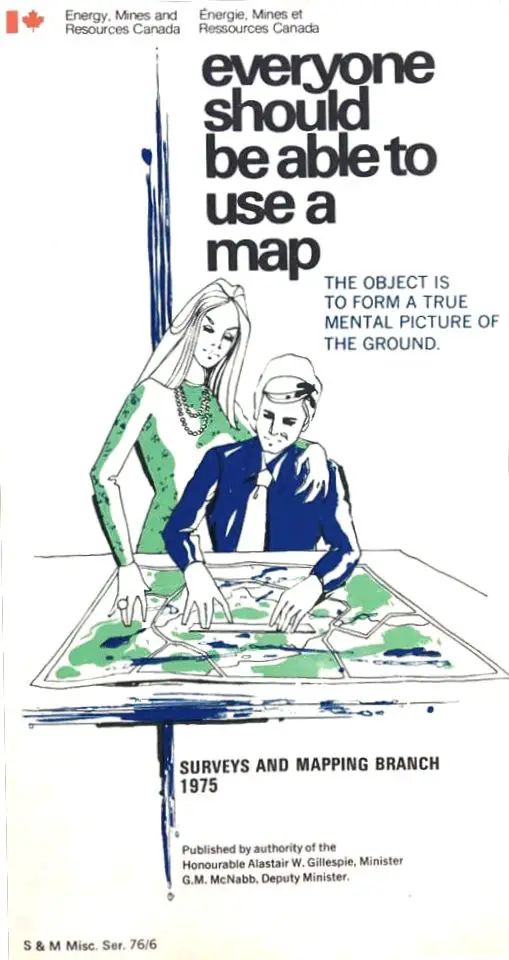

Aphantasia doesn’t seem to affect spatial ability, either:

people with aphantasia have intact spatial imagery abilities – the ability to represent the size, location and position of objects in relation to each other. […] We also found similarities in performance within the classic mental rotation imagery task, in which people look at shapes to work out if they are the same shape rotated or different shapes.

Aphantasia explained: some people can’t form mental pictures

Where aphantasia may prove challenging:

[S]ome people with aphantasia – but not all – are more likely to report difficulties with recognising faces and also report a poor autobiographical memory – the memory of life events – a type of memory thought to rely heavily on visual imagery.

Aphantasia explained: some people can’t form mental pictures

Some people with aphantasia ‘see’ images in their dreams. Others don’t dream in images but still have emotional and conceptual dreams.

If you’re a writer and aphantasic and wondering if this holds you back, it doesn’t. You’re in good company.

Scientists have learned more about our various experiences after realising there are people who become aphantasic for the first time after injury. A 65-year-old man lost his ability to form mental images after surgery. (In 2015 Carl Zimmer wrote about this in The New York Times [paywall].)

Well-known people with aphantasia:

- Penn of Penn and Teller (the magicians)

- Craig Venter (the geneticist)

- the list at Wikipedia shows that aphantasia doesn’t stop anyone from success in the creative industries

POSSIBLE SUPERPOWERS

No one really understands why aphantasia occurs in the population (at perhaps 2%) but there is speculation that aphantasia leaves people a bit less prone to PTSD after traumatic events because of the inability to recreate the trauma in the mind’s eye. There may be advantages when it comes to the grieving process, too.

HYPERPHANTASIA

People who ‘see’ descriptions with the most clarity are at the ‘hyper-phantasic’ end of the spectrum. This might sound like a cool superpower, and it is, but it comes with its challenges. Hyperphantasics can reach overwhelm more easily. Loud movies in a theatre on a big screen can be too much. Hyperphantasics don’t necessarily want to remember every experience, especially the negative ones.

POSSIBLE SUPERPOWERS

- The ability to visualise a route, sort of like having a Google Maps street view in your mind.

- Having a memory that feels like watching a movie

- Some hyperphantasics are able to recreate sounds and smells as if they are real, not just visual images. Hyperphantasics are more likely to have synaesthesia, in which senses overlap: sounds may have a smell, days of the week may have a colour etc.

- Very good eye witnesses in a crime. Able to provide plenty of information for an Identikit sketch.

WHAT DOES THE PHANTASIA SPECTRUM MEAN FOR WRITERS AND READERS?

I hope I’ve conveyed the extent to which everyone is different, even within these broad labels. Borrowing from autism activism, “You know one aphantasic, you know one aphantasic.”

Many readers with aphantasia have no trouble at all reading all kinds of books.

That said, it’s reasonably common for aphantasics to enjoy non-fiction more than fiction. When reading fiction, perhaps surprisingly, some aphantasic readers skip paragraphs of description. (Phantasic) writers may assume that verbal descriptions are more necessary when catering to someone who is unable to see a scene in their mind’s eye, but the inverse tends to be more true: A list of facts about a scene are boring and unhelpful.

I don’t think you have to be aphantasic to avoid paragraphs of description. Perhaps the trick is to help readers who want to skip, skip. This would be a matter of paragraphing. Put description in its own paragraph.

An aphantasic writer may naturally skip the paragraphs of description. This might make an aphantasic writer naturally good at fast paced stories, perhaps for an audience with a smaller tolerance for flowery descriptions (i.e. children).

The good news is: Wherever you fall on the phantasic spectrum, there are others in the world like you. Write what you’d like to read yourself, and you’ll find your audience.

For people who know or suspect they are aphantasic, if you have trouble reading for whatever reason: audiobooks and graphic novels are perfectly valid ways to enjoy story. It’s perfectly fine to read nothing but audio books and graphic novels, and you’d still never run out of reading material in a lifetime. Although plays aren’t designed for reading, aphantasic readers may get a lot out of reading stories in their script form.

Some works of fiction are experimental to the point where they suit many aphantasics very well. One example might be The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, with its emphasis on words rather than description.

RELATED CONCEPTS AND WORDS

Hyperthymesia

An uncommon ability which allows spontaneous recall with great accuracy and detail a vast number of personal events or experiences and their associated dates. People with hyperthymesia can recall almost every day of their lives in near perfect detail.

Some people with hyperthymesia also have aphantasia. Someone who is both hypherthymesic and aphantasic has a fantastic memory for detail, but their brain doesn’t take any ‘snapshots’ to store alongside those details.

SEVERELY DEFICIENT AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORY (SDAM)

This is like the inverse of hyperthymesia. It overlaps quite a bit with aphantasia.

The inability to ‘mentally time travel’ is the latest memory condition to intrigue researchers – and as most people with it likely don’t realise, it may be more common than we think.

BBC Future

People with SDAM live in the moment. Nostalgia isn’t possible, and nor is daydreaming a thing. But there’s an advantage when it comes to trauma.

These conditions are not the a result of lived trauma in an individual, but is it possible evolution has selected for SDAM and aphantasia due to collective trauma across a community?

NEURODIVERSITY VS NEURODIVERGENCE

Many people mistakenly use this word to refer to individuals e.g. “This person is a neurodiverse person”. Autism is currently the most widely example of brain difference.

But a single person cannot be ‘neurodiverse’. A single person with non-typical wiring is ‘neurodivergent’. Diversity requires multiple separate examples within a group.

Take any group of humans and you find neurodivergence. Aphantasia and hyperphantasia are examples of neurodivergence, alongside dementia, schizophrenia and all of the brain differences which exist in the human world.

SIMILAR SOUNDING WORD

Aphantasia is easily confused with aphasia: a disorder that results from damage to portions of the brain that are responsible for language.