Petunia the Silly Goose is a character created and illustrated by Swiss-American Roger Duvoisin (1904-1980). The first of the series was published in 1951. Petunia’s Christmas came along the following year.

Find Petunia’s Christmas available for one hour loan at The Internet Archive.

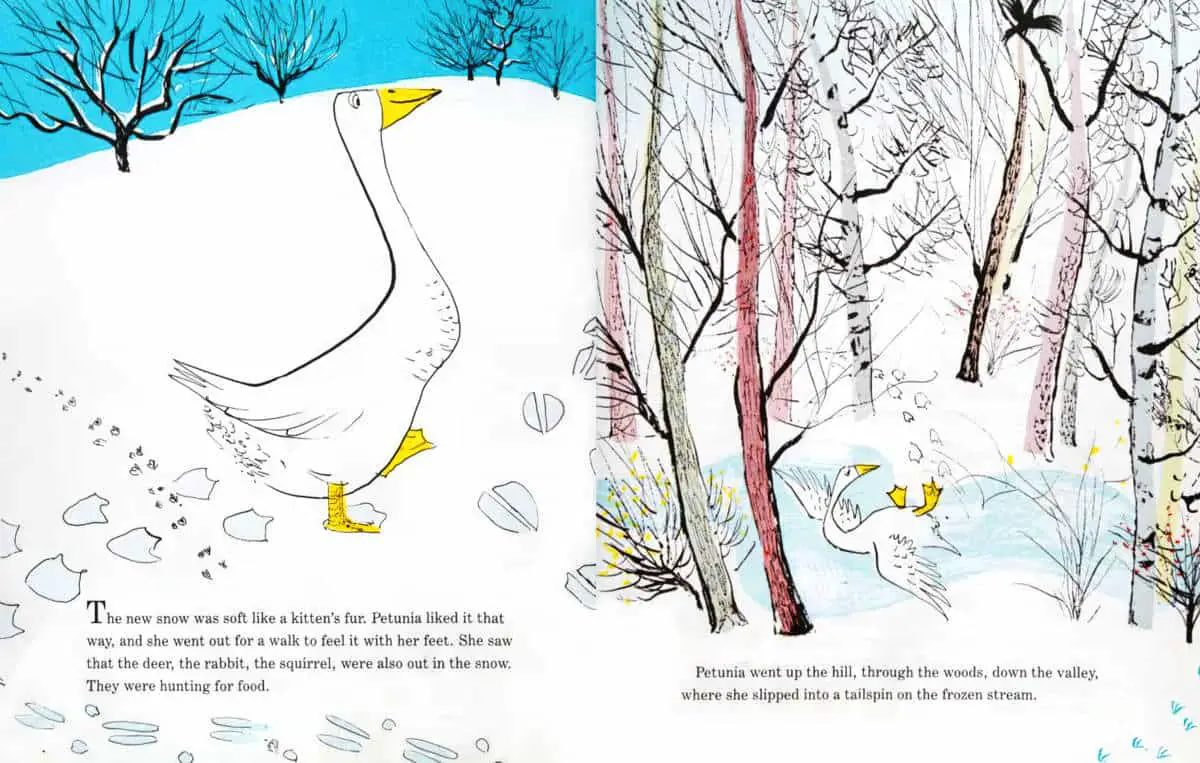

Once again, Petunia’s story starts when she is simply out for a walk, minding her own business. In the first story, she came across a dropped book and considered herself very smart. In this one she slips on a frozen stream and is taken by surprise on an unintended journey.

The illustrations are once again unmistakeably Duviosinian, with white space for snow, and splashes of Duvoisinian blues, pinks and yellows.

At first glance, Petunia appears to be alone as she walksa cross that lovely soft-looking snow, but many others have taken this path before her. Young readers are encouraged by the text to identify each set of footprints.

One standout feature of geese, and particularly of this goose: The long neck. Petunia sticks her head into a hole in the snow and searches for food. She’s getting hungry.

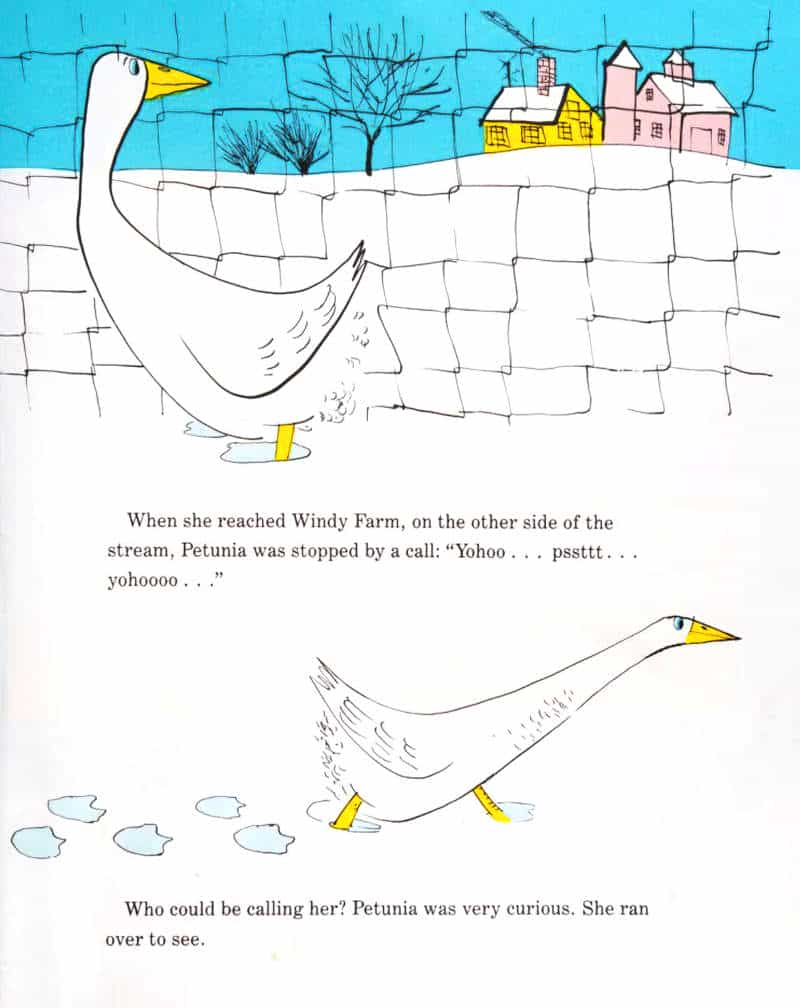

Eventually she reaches a place called Windy Farm. I’m not surprised — don’t these farmers know to plant some foliage as wind break? Or maybe they tried and everything died. (How dystopian is this story?)

Note to modern young men reading this book: This isn’t how to pick up a modern chick. Everyone has moved to the dating apps now. Stopping a woman on the street and saying “Yohoo!” is, admittedly, quaint, and may work for some very specific individuals in very specific circumstances. I’m not sure a big fan of the “Psst”, though.

Next, Petunia meets Charles, who stands behind a wire fence, imprisoned. The horrific part of this story: Charles is fully aware of his fate. He knows why he’s being fattened up.

Charles wonders if Petunia, too, is being fattened for a grim purpose. Petunia explains her privilege: She is a pet, not a foodstuff. Charles requests Petunia’s help in escaping from his enclosure. The smitten Petunia decides to hatch a plan. She mulls this over on her long, plodding walk towards home.

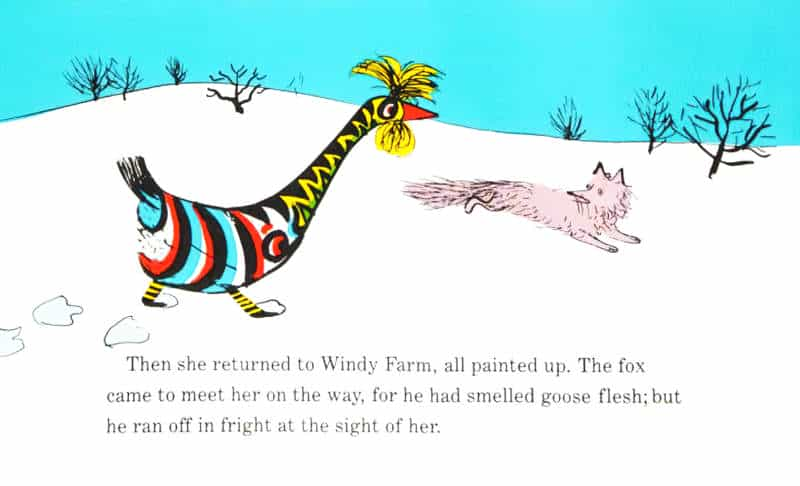

Although Petunia started out as a ‘silly goose’, remember she learned to read after finding that book? Well, she comes up with a rather good idea. She paints herself in a distinctive Duvoisian palette of colours to look like a fierce monster. She even scares herself she she looks in the mirror.

GOOSE FLESH

If Duvoisin didn’t mean to turn a generation of young readers into vegetarians, perhaps he shouldn’t have written books with these plot lines. Perhaps he might have avoided the word ‘gooseflesh’. Like any part of the body ending in ‘hole’, ‘gooseflesh’ simply reminds readers that we are reading about a foodstuff, not a character.

This got me wondering: How many words end in ‘flesh’?

Apart from gooseflesh and horseflesh English has parflesh, meaning a rawhide soaked in lye to remove the hair and dried.

This word looks to me like an American-English spelling from French parflesche, from parer meaning “to parry” or “to defend”, and flèche meaning “arrow”. “Parfleche” was also used to describe tough rawhide shields, but later used primarily for these decorated rawhide containers.

DUVOISIN AND STEIG

The illustration of Petunia in war paint tells me that Duvoisin must have had a major influence on William Steig. Or perhaps the two men influenced each other, I don’t know. In any case, check out Steig’s The Amazing Bone and you’ll see what I mean. I’d say Steig is a bit more quirky, in general, whereas Duvoisin is more earnest.

Petunia successfully scares the farmer by coming at her with wings outstretched, making “war-honks”.

FARMERS IN 20TH CENTURY PICTURE BOOKS

Note that a farmer’s “wife” does farm work, and is seen doing just that here, but is rarely, if ever, called simply a “farmer” in 20th century literature.

The farmer leaves the gate open and Charles if free!

FOOTPRINTS

We knew from page one that footprints were going to be significant in this story. The two geese lovers can’t get away scot free because they leave distinctive goosey footprints in the snow.

Now the “real” farmer goes in search of Charles, the big, expensive goose who he meant to sell for a hefty sum. He carries a rifle.

Fortunately, the neighbour man is Mr Pumpkin, who keeps Petunia as a pet and I assume does not eat “gooseflesh”. Unlike the owner of Charles, Mr Pumpkin does not carry a rifle. He smokes a pipe. “Don’t shoot!” He’ll kill you slowly with second-hand smoke instead, I guess.

Mr Pumpkin finds Charles hiding in a haystack inside the barn. Poor Charles looks terrified. Duvoisin shows expression by modifying the beaks into smiles and frowns, and by giving the birds human eyes.

The farmer puts Charles on a leash and leads him all the way back “home”.

PETUNIA IN LOVE

Petunia is absolutely distraught. What will she do without Charles? Fortunately she understands English and knows exactly the amount Charles can be sold for. Twenty pounds and seventy-five cents. (An oddly specific amount?)

All she has to do is earn it. Then she can buy Charles for herself. Petunia can save the day. But how does a pet goose earn money? What are her skills?

First she tries begging on the street near a bus stop while dressed as a Santa but this doesn’t work. No one is interested in donating. She only gets a few pennies this way.

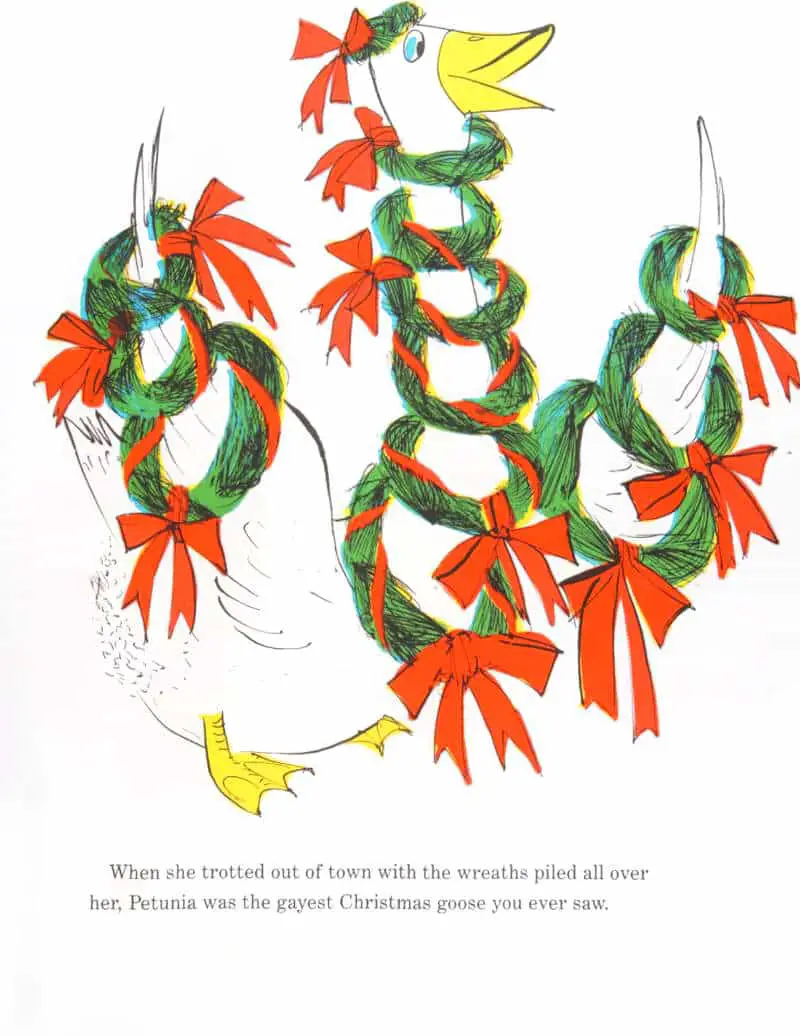

So she goes to the woods, gathers pine twigs and uses these to create Christmas wreaths. When these are a moderate success, she branches out into other kinds of Christmas decorations, which people buy happily.

THE MESSAGE OF PETUNIA’S CHRISTMAS

The (outdated) capitalist message of Petunia’s Christmas is clear: If you have the ability to do something industrious, don’t rely on charity. Use your initiative and start your own business, working constantly on self-improvement. Those with a keen eye for a hole in the market will be rewarded.

Rewarded she is. Petunia earns enough to buy Charles’ freedom. But the farmer and his “wife” realise that Petunia must be in love. Since everybody loves a love story, they refuse to take her hard-earned coins and donate Charles to Petunia.

THE GENDER INVERSION

I’m glad this wasn’t a tale about Charles “buying” Petunia. That would never have worked. Why? Because it’s too close to the reality of the world. For centuries, women have literally been treated as chattel. But now we have a gender inversion and it doesn’t seem as creepy.

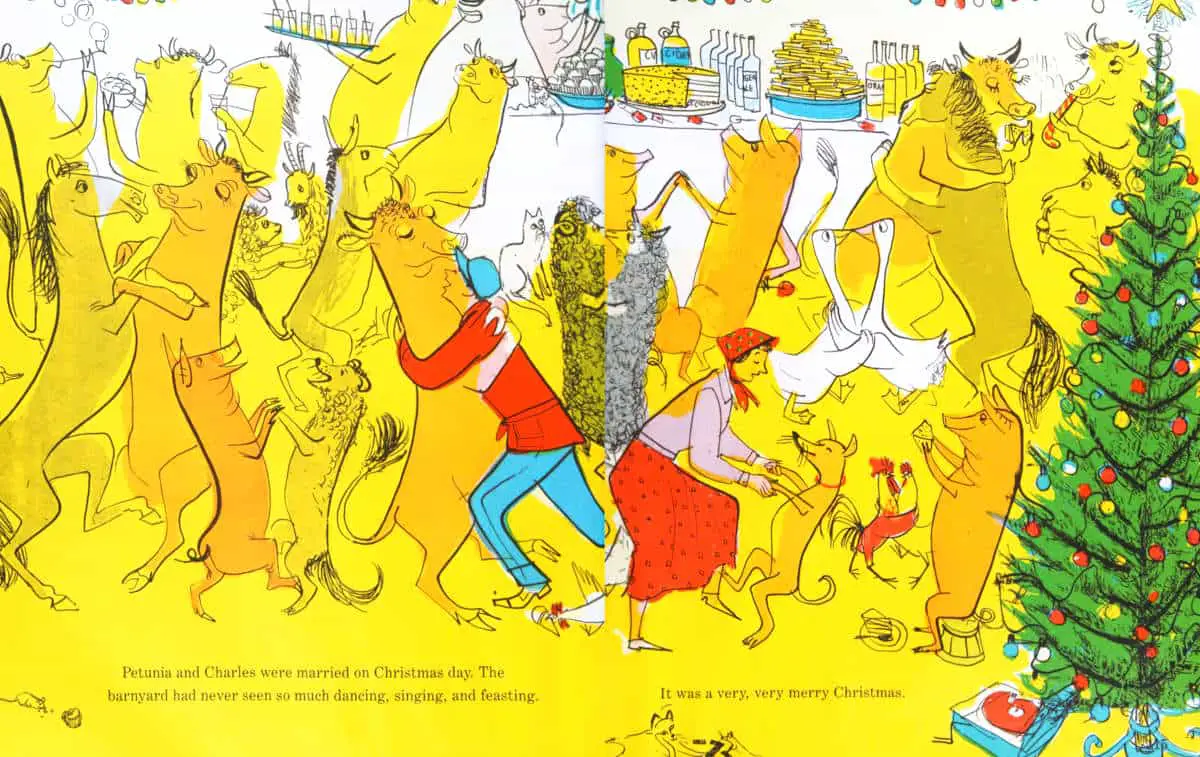

Since Petunia is a good girl, she gets married before getting it on with Charles. Here’s a wonderfully lively scene of the wedding shindig. Judging by the Christmas tree, this was a hasty affair:

WHAT HAPPENS TO PETUNIA AND CHARLES?

The outro page is an image of geese followed by baby geese. First comes love, then comes marriage, then comes a whole lot of babies all at once.

Since Mr Pumpkin keeps Petunia as a pet, we might guess these two live happily ever after. However, everyone has a price. How many babies did successful breeders Petunia and Charles create before Mr Pumpkin decided he might as well make some extra cash at Christmas?

Apparently it is possible to purchase visy vests for your poultry. Why? I have no answer. So they can be put to work on building sites?

Among the more unusual items I’ve seen for sale online are poultry diapers, so I’m guessing there are people in this world who keep their poultry pets inside. Being an erstwhile chicken keeper myself, I know how much personality they have — birds are every bit as individual as cats and dogs. Domesticated poultry also prefer to be around humans if they can, and will sit outside your door. If you open the door, they’ll invite themselves in.

So yes, I can see how items like these happen.