“The Pearl” is a novella by John Steinbeck, first published hot on the heels of the second world war. The story is a re-visioning of a Mexican folktale, sometimes called a parable. This story is widely studied in American high schools so much has been posted elsewhere about symbolism and themes. My focus is on the structure and storytelling techniques, from a writer’s point of view.

The following song is based on John Steinbeck’s story.

THE ILLUSION OF CAUSALITY

This story reminded me of a half-forgotten memory. I’m four or five, sitting on the carpet in the living room at my Nana’s house. Nana goes to her bedroom, comes back with a ring and says, “See this ring? That’s yours when I die.” I can’t really see the ring from where I sit on the floor, but I nod obediently. A year or so later, Nana is killed by a car while crossing the road to buy milk at the dairy. I never see that ring again, because my father insists it’s cursed. First it belonged to an auntie of his — an auntie who died. Now his mother has died. Obviously, to his mind, the ring itself is bad luck.

That’s how inheritance works, of course — a ring isn’t passed down until its owner dies. If everyone were affected by the same cognitive bias as my father we wouldn’t see older women walking around with hands full of inherited rings.

The illusion of causality is at work in Steinbeck’s “The Pearl”, too, as humble villagers are corrupted by greed as soon as they come into some material good fortune. The oversized pearl itself is blamed, when in fact pearls are just pearls. Bad deeds are carried out by imperfect humans.

CHARACTERS OF “THE PEARL”

Kino — small build, wears a suppliant hat, native to Mexico, no money. Owns a canoe and spends his days diving for pearls and fishing to feed his family.

Juana — Kino’s obedient wife who has recently given birth to their first baby. Her life revolves around her baby. Juana is your classic Female Maturity Formula. She realises the evil in the pearl much earlier in the story, functioning as a Cassandra character. If only she weren’t under the thumb of her husband, who knows best according to the laws of patriarchy, they could’ve returned the pearl to the sea and their baby would have lived.

Because of the Female Maturity Formula, authors like Steinbeck are often let off the hook, because, as the following Goodreads commenter says:

In …The Pearl, Juana is the true hero of the story whose place is behind her man until the end, when they walk “side by side” when before, she always had to walk behind him. They only survived each scenario because of her and her ideas. Based on that, you make the call.

Goodreads

I disagree that Juana is ‘the true hero’. The viewpoint character is Kino, Steinbeck spends the first chapter getting us to side with Kino, and Juana remains unrounded. We never see her interiority at all. The same has been said of Mad Men’s Peggy and Joan, as a get-out-of-sexism free card for the creators, but I don’t buy ‘women as true/secret/sleeper heroes’ precisely because of the long history of unrounded woman characters.

Coyotito — their baby (At first I thought Coyotito referred to a bird! Just me?)

The Doctor — a French man who considers poor people animals, and whose fat body symbolises his greed.

Juan Tomas — Kino’s brother

Apolonia — Juan’s wife

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE PEARL”

The story begins with two characters waking up. Many children’s picture books open with the beginning of a day, and end with our main character falling asleep. There is an inherent cosiness to a story which takes place over 12 hours — as if to say, “This too shall pass — tomorrow is a brand new day.” This story takes place over a number of fraught days, but we don’t know that yet.

It is difficult to write an original waking up scene. It has been done many times before. Here, Steinbeck is describing an idyllic morning — at least for Kino, who gets to sit around watching ants while his dutiful wife, always awake before him, sets about preparing their breakfast.

It was a morning like other mornings and yet perfect among mornings.

This is Steinbeck describing the iterative. He is yet to switch the reader to the singulative. This technique of opening with the iterative is again very common in children’s books, because it feels cosy. Routine is reassuring.

The first clue we have that not all is perfect in this world is mention of the ‘poisonous air’ of night-time. It was common long ago around the world for people to believe that illness was caused by ‘night vapours’. Darkness itself was feared, as much as the things that come out of the dark.

MAKING USE OF THE MINIATURE

John Steinbeck likes to remind readers of differential scales — he did it in “The Leader Of The People” and he does it in the opening, as Kino observes the ants, transforming himself into ‘god’.

The ants were busy on the ground, big black ones with shiny bodies, and little dusty quick ants. Kino watched with the detachment of God while a dusty ant frantically tried to escape the sand trap an ant lion had dug for him.

For more on The Miniature In Storytelling see this post. But why does Steinbeck use it in this particular story? Abundance does not cause satiation in humans; it causes anxiety and greed. The size of the pearl, and the size of Kino (godlike in comparison to the ants), coupled with the dream of the massive book with giant letters, all serve as symbols of (over) abundance.

The pearl in this story is as big as a duck egg, beyond anything known at the time. FYI, the world’s biggest clam pearl was found in 2006 in the Philippines and sold for $130 million. The pearl in Steinbeck’s story should, by market value, provide Kino’s entire community with enough to live on for generations to come.

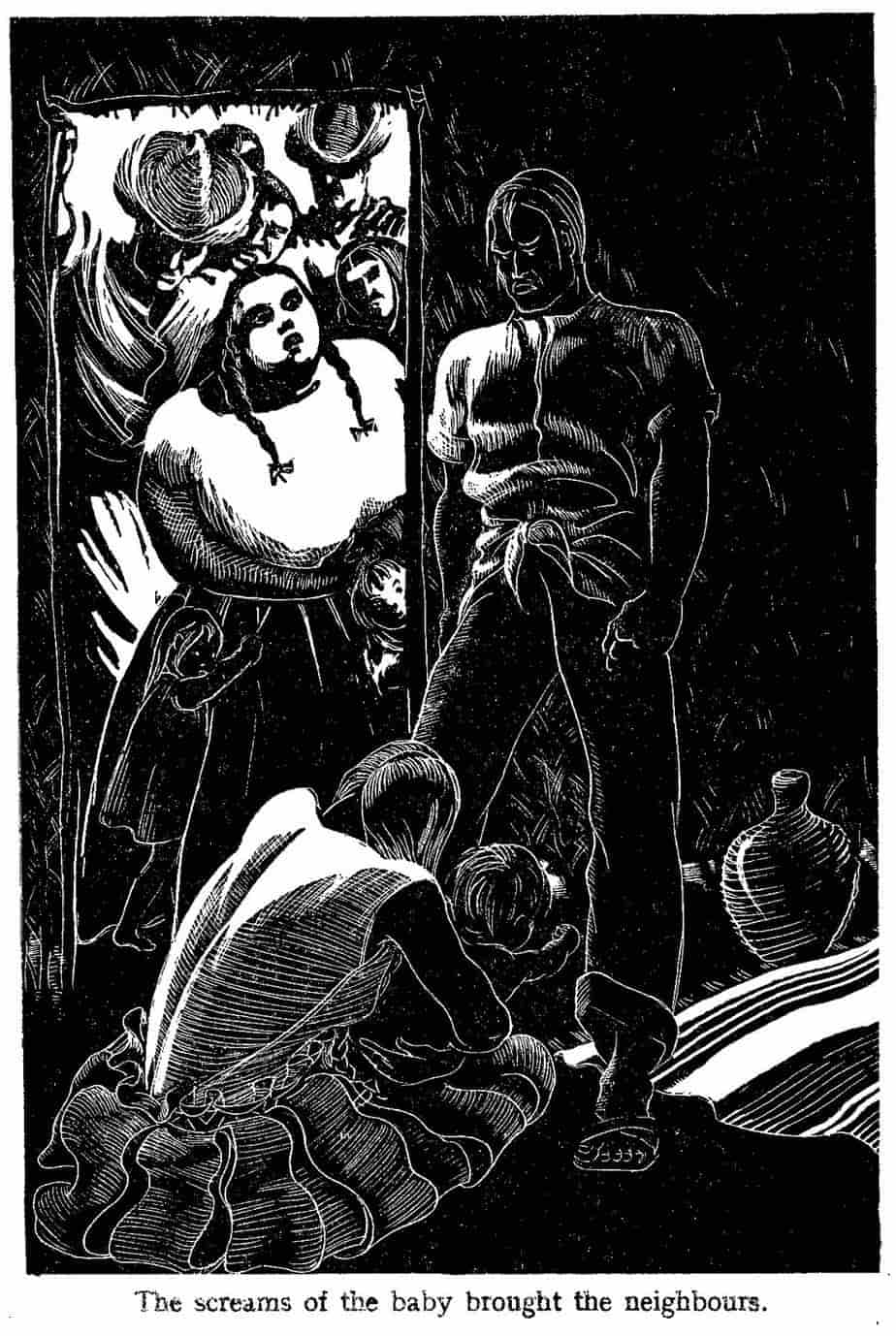

SHORTCOMING

Kino and Juana are classic fairytale underdogs — they show no moral shortcoming. Nor do they show much in the way of psychological shortcoming, other than Kino taking his anger out on the gate and splitting his fist. (He may suffer from a self-destructive temper.) Instead, this pair have a problem: Their baby’s life is in danger after being stung by a scorpion. Apparently scorpions can cause convulsions and shortness of breath — these two are right to be worried about their baby.

Their related problem is that they have no money to pay the doctor.

Chapter One, which ends with Kino punching the fence in frustration, is almost a self-contained story in its own right, complete with problem, desire, plan, opponent, big struggle and a tragic ending. The only thing it doesn’t contain is the anagnorisis. For that we must read the rest of the novella.

However, though my modern lens, I find Kino’s violence wholly unacceptable. I put forward two main reader interpretations of Kino’s character after we see him punching the fence:

- Kino is expressing his frustration in an appropriate way, since fences are not able to feel pain and he is justifiably angry.

- Kino’s physical expression of rage hints at an uncontrolled temper, dangerous for his wife.

I went with number two, because I don’t trust people who punch anything out of rage. Sure enough, later in the story Kino bashes his wife’s face to the point where her wounds are attracting flies the following day. To me, Kino was never a pure-hearted fisherman corrupted only after the pearl was found. I suspect he was always a wife beater, hence his wife’s manic vigilance, conveyed via the creepy spectacle of her watching her husband each morning, then springing into action with a cooked breakfast once he awakes.

However, is this what a typical mid-century reader would have thought? Just 50 years ago doctors were recommending men beat their wives as ‘temporary therapy’. Kino is clearly depicted as an increasingly flawed human in this story, similar to the ‘breaking’ of Walter White, but I feel it would be a mistake to assume mid 20th century readers would have roundly criticised Kino for punching his wife in the face. I suspect judgement of Kino would have come later in the story for many.

DESIRE

This is a story of escalating desires, and the human tendency to be dissatisfied, which Steinbeck’s narrator tells us is the reason we are elevated above the animals (who are happy with their lot). Permanent lack of satiety is both our shortcoming and our strength.

Because this is a major theme, Kino’s desires escalate as the story progresses, beginning with a man who wants for nothing.

- Kino and Juana are happy as they are, but when their baby is bitten by a scorpion they would like a doctor to make their baby better.

- They would like money or a valuable pearl to pay the doctor.

- After finding the pearl, they want to fetch enough money to pay for their son’s education.

- Kino wants to escape the faceless, unnamed evil coming after him in his own village.

OPPONENT

The first opponent is the doctor who refuses to heal their baby without payment. He tries to persuade Kino that their baby’s eye is blue. I’m reminded of the people who call from ‘Microsoft Windows’, who then tell you to go into the bowels of your computer to view all sorts of normal running messages, then try to tell you that your PC is riddled with viruses.

The second opponents are the pearl buyers whose mission is to pay as little as possible for anything, despite being salaried themselves. Like the doctor, these are tricksters who make use of Kino’s lack of knowledge about pearls to try and persuade him that his pearl is defective under a magnifying glass. Anyone with basic knowledge of pearls understands that pearls are supposed to look unusual when magnified — this is the very thing that distinguishes them from fakes.

Even the obedient wife Juana becomes Kino’s opponent when she tries to get rid of the cursed pearl.

Why are the pursuers faceless and nameless? Wouldn’t it be more thrilling if the reader knew who these men were and what they are capable of? Perhaps, in thriller tradition, yes. But by remaining faceless these men better symbolise the evil that resides within Kino himself.

PLAN

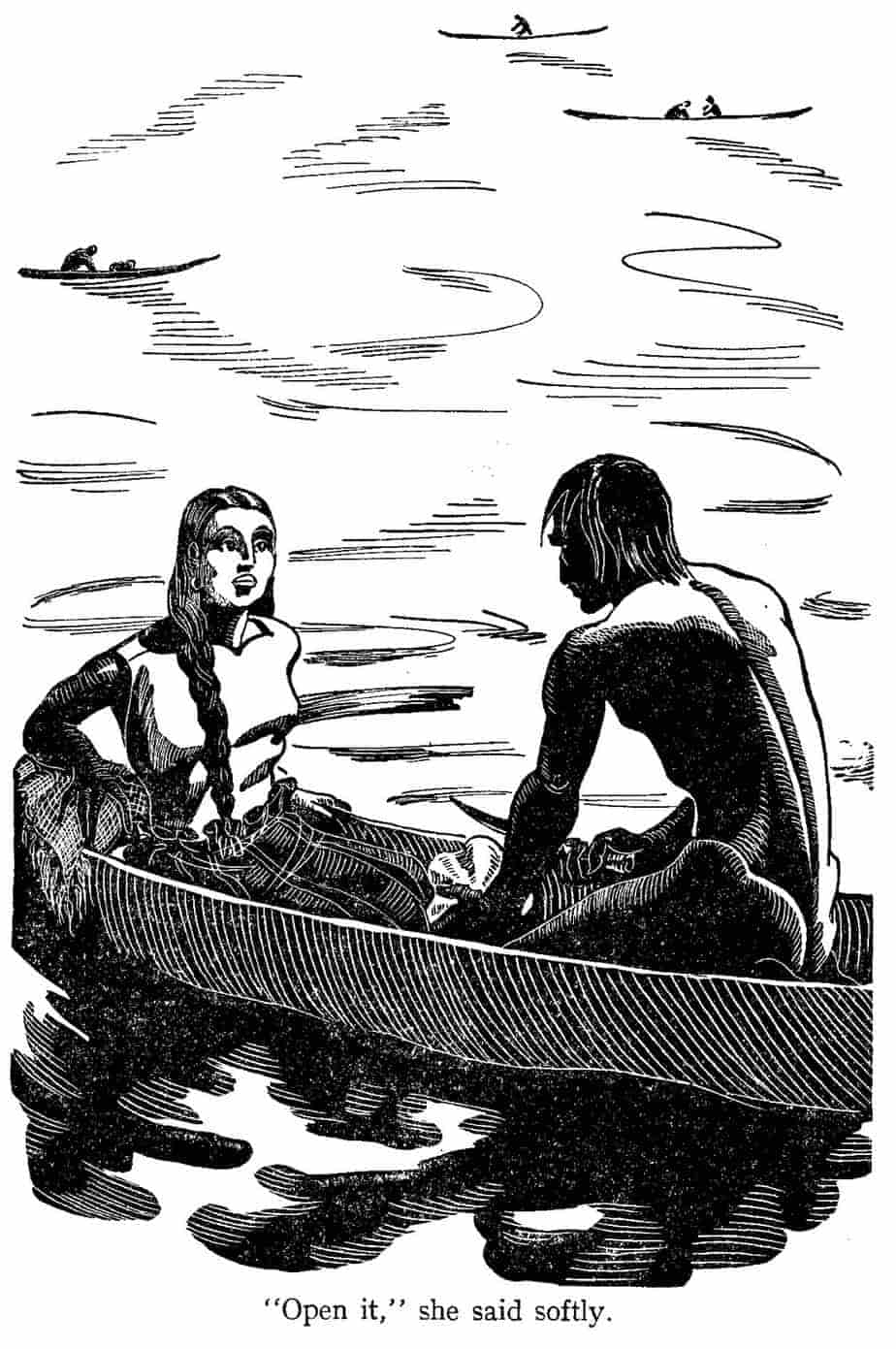

The plan to take their baby to the doctor fails so Kino and Juana try their luck finding a valuable pearl. They are magically rewarded with a massive pearl, which seems to cure their baby instantly.

Kino plans to sell the pearl so he takes it to local pearl sellers, but he can see they are trying to swindle him.

The next plan is to take it to the city, which scares him. He has never ventured outside his own village. But that night he his thwacked in the head. Juana tries to throw the pearl into the sea but Kino stops her and hits her.

When Juan accidentally kills a man who attacks him he and his small family take refuge in his brother’s hut while everyone else speculates about what happened to him.

BIG STRUGGLE

After an exciting chase sequence, the baby has the top of his head shot off by the men on horses who pursue Kino.

When Kino and his family are chased into the wilderness, this is a metaphor for Kino entering deep into his own subconscious. Very Freudian. Very fairytale.

ANAGNORISIS

Kino comes to the conclusion (too late) that his wife was right — the pearl brings evil. He gets rid of it. He has seen the evil in humanity and within himself, no longer godlike, as he saw himself at the beginning of the story, overseeing those shiny black ants.

NEW SITUATION

Back in the village, this couple will lead a miserable life, forever changed by the murder of their firstborn, and also by the hopes and dreams held temporarily after securing a valuable pearl.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

There are many folk tales about greed, in which we learn that more does not mean better. This moral never gets old, and is only more salient today.

A picture book example is More and Better by Margaret Neve.

“King Bait” by Keri Hulme is a short story for adults, similarly fabulist, in which abundance immediately corrupts.

John Steinbeck was a renowned misogynist and it’s difficult to read his wife’s description of him without mapping Steinback himself onto Kino.

There are a lot of similarities between Breaking Bad’s Walter White and Kino — both men tell themselves that they’re doing what they do for their family. But there’s a saying that there are always two motives for doing anything — one is the noble one, the other is the real motive. The ‘noble’ motive in both cases is ‘I’m doing what I do to provide for my family’ but the real motive is ‘power’.