Pax is a middle grade novel by Sara Pennypacker about a boy and a fox who embark upon a mythic journey to reunite after Pax is abandoned in the woods. Structurally, Pax is the middle grade equivalent of Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier. Though this story is classic mythical structure, there are shades of the Female Mythic Form, as the main character Peter (who happens to be male), thinks and feels his way through his journey rather than engaging in battle after swashbuckling battle.

MORE ON THE STORY STRUCTURE OF PAX

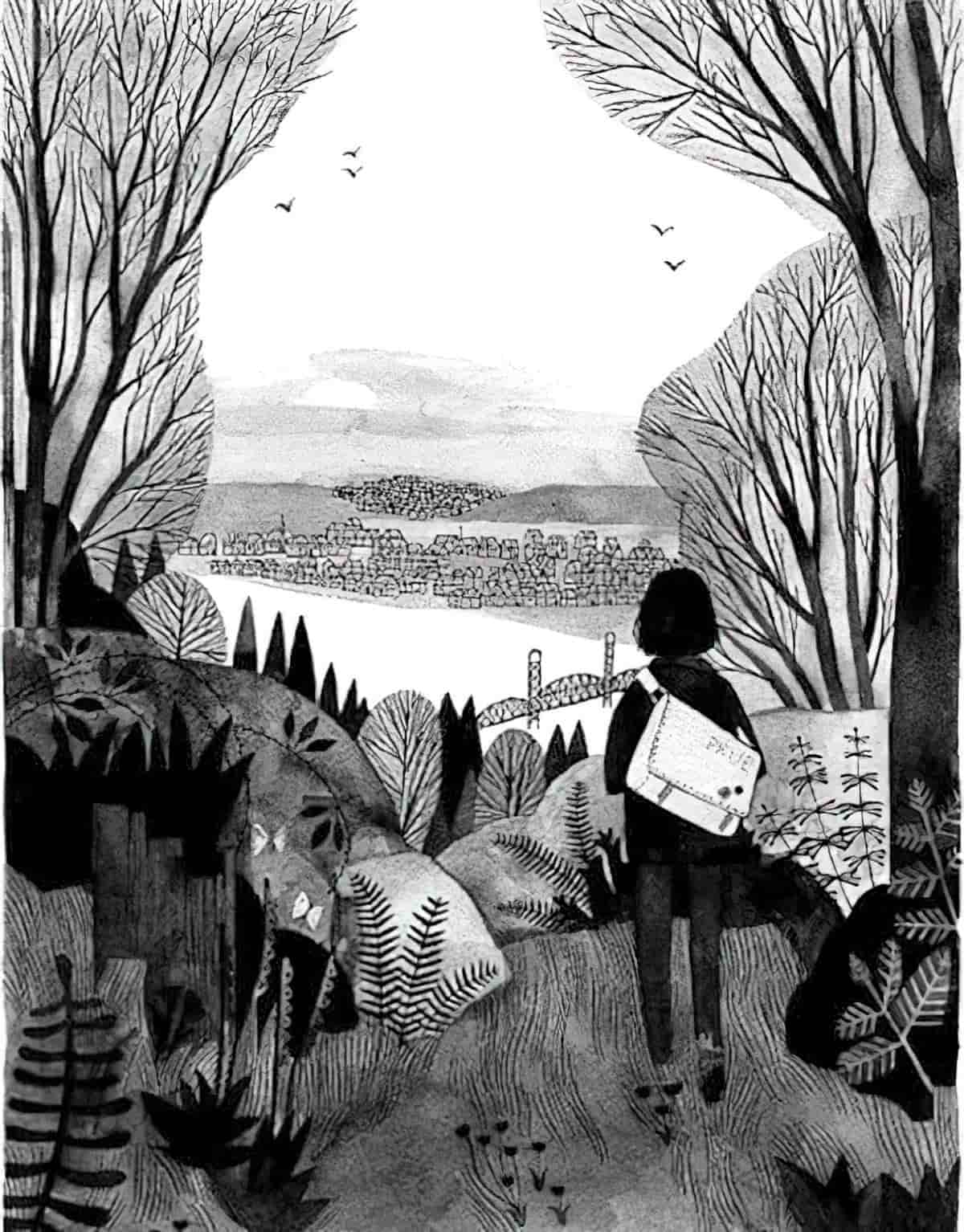

Pax was only a kit when his family was killed, and “his boy” Peter rescued him from abandonment and certain death. Now the war front approaches, and when Peter’s father enlists, Peter has to move in with his grandpa. Far worse than being forced to leave home is the fact that Pax can’t go. Peter listens to his stern father—as he usually does—and throws Pax’s favourite toy soldier into the woods. When the fox runs to retrieve it, Peter and his dad get back in the car and leave him there—alone. But before Peter makes it through even one night under his grandfather’s roof, regret and duty spur him to action; he packs for a trek to get his best friend back and sneaks into the night. This is the story of Peter, Pax, and their independent struggles to return to one another against all odds. Told from the alternating viewpoints of Peter and Pax.

publisher’s advertising copy

- From the advertising copy we see there are orphan and part-orphan child(like) characters: Pax has no parents and Peter has no mother.The father is soon dispatched with, too.As it happens, Peter has no grandmother, either. Women have been removed from this story altogether, possibly because a feminine presence adds tenderness and care, whereas these characters are extremely vulnerable and must find their own family. However, Peter eventually meets a mother replacement, and Pax eventually meets the fox equivalent of a girlfriend. These female characters add to the character growth of the male characters, and a little vice versa as well.

- A mean grandfather is left as Peter’s caretaker, leaving plenty of room for Peter to go off on his own adventure.

- The toy soldier is symbolic, and features front and centre in chapter one. Toy soldiers juxtapose the innocence of childhood with the awful destruction of war. At the end of the story Peter literally throws the toy away. That’s what he thinks about war.

- The basic setting: pre-war — the author aims for universality and doesn’t name a war, though I default to WW2.

- We also learn from the advertising copy that this story is a classic example of mythic structure, about a boy going on a journey with a goal in mind, returning home (or to a new home) a changed person. (Or animal.) He will encounter a series of trials and opponents along his way, finding himself in greater and greater danger until he reaches his ultimate big struggle. Then he will have an anagnorisis.

Advertising copy stops before the middle of the book, not giving too much away. More of the structure is revealed as we read:

- In the hero’s journey, at about the midpoint the main character really doubles down on their mission (plan + desire). So when Peter overextends himself with exercises at Vola’s, this is that. “It takes a healthy adult four weeks to do what you’re trying to do in one,” Vola tells him. This is evidence of Peter’s extreme determination, almost superhuman.

- The big struggle scene features ‘mythical’ creatures, coyotes, who are not anthropomorphised at all.

- Peter’s anagnorisis is that he is actually separate from his pet fox, but because of the bond they shared in the past, they will always be together. The problems with the ending are discussed below.

My description of this story structure sounds a little dismissive, but The Hero’s Journey is a structure that has worked for 3000 years, and continues to be popular in contemporary stories for adults and children alike.

SETTING OF PAX

Peter comes from a town called Hampton.

The grandfather’s village is a fairytale village north of Hampton, but a highway snaking around a long range of foothills. It is surrounded by woods. All fairytale settings need woods (or forest) on the edges of civilisation. There’s also a road, and Peter will be guided by a map. Pax has been abandoned 300 miles away beside the ruins of an old rope mill, which I guess is a factory which makes ropes. An olde worlde type establishment. 300 miles is a decent distance to put between the boy and his dog — an adult reader (at least) knows from the outset that 30 miles per day is an impossible undertaking. Peter’s going to have to be resourceful and hitchhike or something, otherwise he’ll never make it.

When Is This Story Set?

Peter has access to items of the early 20th century era: He carries a jack knife, not just uses but is reliant upon maps, and food is kept in tins rather than plastic containers. He has no access to technology that might help a modern child out. Though this is about no war in particular, it should put us in mind of the Great Wars of the 20th century. The technology lines up (mostly) with this era.

Before I realised this was set in no year in particular, I tried to do a few sums: Perhaps this is a WW2 story, and the old fox was around for the first world war. No, that’s not possible. Grey foxes live longer than red foxes, but WW1 ended 1918 and WW2 started 1939. Grey foxes live a maximum of 8 years.

It becomes clearer as the story progresses that Sara Pennypacker wants to set this this story in a ‘universal’ time and place. Though to me, a non American, it feels very American, it may not feel that way to an American audience. The baseball, the (Californian) talk therapy, the American vernacular, which I occasionally even looked up. If an American audience doesn’t see how American this is, expecting it to sound universal to everyone, that would be troubling. An interview with School Library Journal shows that Pennypacker very much meant this to sound like it was set in America:

Peter and Pax’s story is set in an undefined time and place—it could be the past or modern day or the near future. It might take place in America but not necessarily. Why did you set your story against this type of backdrop?

I didn’t want to allow readers the comfort of seeing the setting as “another”: another place or another time. My goal was to have readers feel that what happens in the book could happen in their town tomorrow. Because, sadly, it could.

SLJ

Which is great. I mean, Americans need to hear this particular message about war. But from this outsider’s point of view, this is definitely America.

Magic

Whereas ancient mythical journeys often feature real setting magic, the ‘magic’ Pennypacker describes is a feeling rather than a phenomenon:

Peter craned his head to see what [Vola] was making. A handle. She’d brought i a broken hoe, and she was giving it a new handle. A simple thing, and yet it struck him as almost magic. Like his crutches. Before he’d had them, he’d been helpless. Vola had nailed a couple of boards together, and now he could swing over miles of rough country, quick and sure. Magic.

However, Pennypacker does delve into some new age mind-meld stuff, in which Peter feels he can sense how much trouble Pax is in.

“Two but not two. Inseparable. So… a couple of nights ago, I was sure that Pax had eaten. I felt it. Last night, I saw the moon, and I knew Pax was seeing it right then, too.”

CHARACTERS IN PAX

Peter

The name Peter has a literary, old-fashioned quality to it e.g. from Peter and the Wolf and many other fables and fairytales throughout history. Peter is also fairly common as a name for contemporary(ish) boys, linking the old with the new.

Also, Peter is The Every Boy. He is basically a good child, exhibiting all of the qualities we hope children to have. He obeys his father, even though the father is asking him to do something terrible. Peter has no real distinguishing features, and his main shortcoming is naivety and vulnerability owing to basically being abandoned.

The book began with character—it was always going to be a sentient animal commenting on human war. In the beginning, though, Peter didn’t have his own narrative—he was merely going to be “the boy” who belonged to my main character. But I saw such richness in inviting him to tell his side that halfway through writing Pax, I opened the book up.

SLJ

We are shown Peter’s caring nature from chapter one, when he shows emotion at having to send his beloved pet fox back into the wild. Though he is crying, this is a rare thing for him, showing that although he is emotional, nor is he a ‘crybaby’. He cries softly and silently, which is an acceptable way for children (and especially boys) to cry, especially in the early part of last century. I argue that Peter is a good role model for caring about others and expressing emotion, which makes this male plot structure feel more feminine once you delve into it.

Peter is also an optimist — a naive optimist — thinking that Pax will be waiting right where they left him, and also that he can walk 300 miles in a week. At the other end of the journey, Peter plans to stay in his old home alone, with no one at all to provide food for the duration of the war. This plan is Peter’s psychological shortcoming, which has an adorable flip side.

Poetic Naming Conventions

Because Peter starts with the letter P, it’s fitting that his ‘spirit animal’ also begins with P. This symbolically links the two characters. Katherine Mansfield also does that in her short story The Garden Party, in which a family is divided by personality, and the characters who are similar in name are also similar in temperament. This is one of those literary conventions which doesn’t carry over into real life, but helps us to understand the character web in a story.

Who knew that a kid and his pet should be inseparable. Suddenly the word itself seemed an accusation. He and Pax, what were they then … separable?

They weren’t, though. Sometimes, in fact, Peter Had had the strange sensation that he and Pax merged.

Like the fox, Peter is also in touch with his full range of senses, including smell. He is impacted by the smell of his horrible grandfather’s kitchen, for instance, which ‘reeks strongly of fried onions’ and which Peter ‘figured the smell would outlive his grandfather’. He also makes good use of his ears, knowing what his grandfather is up to on the other side of the closed bedroom door. He is intuitive, knowing to stay out of the grandfather’s way. In all these ways, Peter is the human version of a fox. He thinks of his anxiety like a snake, linking him further to the animal kingdom.

Peter’s motivation to find Pax is influenced by memory of a baby rabbit killed in his yard after a trap was set up. Rabbits were eating his mother’s tulips. This dead rabbit had a huge effect on him, and though the dead mother seems at first glance like the bigger ‘ghost’/’wound‘, sometimes it’s more minor things that have a greater impact. The death of the baby rabbit to save something like tulips had a huge effect on Peter. The mother’s death, too, is obviously significant in causing Peter to fear death, and especially the death of the fox. But by transferring the death scene from the mother to that baby rabbit, Pennypacker avoids hitting child readers over the head with something completely and utterly maudlin. This is transferred grieving. (For more on this see Death In Children’s Literature.)

(Even the minor characters have their own ghosts — Bristle has a dead sister, for instance, briefly mentioned, but an explanation for why she is so cautious in general.)

In the end it is Peter’s wooden crutch that saves Pax from the coyotes. What’s the symbolism there? Perhaps it’s that loving another creature is a shortcoming, but even if love is a shortcoming, it still conquers all. It was a loving act to let Pax go, taking in a creature with greater needs.

Pax

When animals feature in children’s books, the author must decide the extent of anthropomorphism. Olivia by Ian Falconer is a little girl in a pig’s body. There’s nothing pig-like about her. At the other end of the continuum you have animals who are literally just animals — donkeys eating grass in fields. Then there’s everything in between.

The huge advantage to using a canine creature as a character is the author has good reason to make heavy use of the sense of smell, in a way not usually explored by authors writing about humans (Patrick Suskind’s Perfume is a notable exception, though the heavy emphasis on smell serves to turn the human character into an animal monster.) In Pax, Sara Pennypacker does an excellent job of describing scent, in a synesthesic kind of way, melding scent with emotions and sights and sounds.

We learn in the first chapter that Pax’s main characteristic is ‘loyal’. This is basically a Boy and His Dog story, even though the dog is actually a fox. Foxes are wild creatures and tend to fear humans, but there are examples of some foxes bonding to humans. If they do bond, they tend to bond to human singular rather than to humans in general, which marks them as different from fully domesticated dogs, who will bond to humans in general so long as they’re properly socialised. Knowing this, it’s clear from the first chapter that Pax has bonded to Peter better than he bonded to the father. This explains why it is easier for the father to let the fox go.

Pax doesn’t talk in words, but he thinks in words. His emotions are every bit as complex as Peter’s emotions. Because Pax is abandoned in the first chapter, the reader immediately feels strong empathy for him. Because Pax doesn’t understand the world, Pennypacker describes objects rather than giving them words. This achieves two things: Pax’s naive voice, and allows the reader to work out a small puzzle What is the blue triangle? A bird. What is the long pole? A rifle (maybe). This puts the reader in reader superior position — a form of dramatic irony. When the reader knows there’s a boy with a rifle we are scared for Pax even though Pax isn’t yet scared for himself.

Pax is (almost literally) an ‘underdog‘. If only he’d been an actual dog, like Peter’s father’s beloved childhood Border Collie, then he’d be allowed to stay with his boy.

It emerges during Peter’s discussion with Vola that Pax as an ironic, symbolic name — Pax means peace (in Latin), yet this is a time of war.

Peter’s Father

The father is not a nasty character, especially when juxtaposed against his own father, who is more of a fairytale villain who emotionally, if not literally, locks his grandson inside his bedroom and provides zero emotional warmth. The father actually does what any reasonable father would do — with good intentions, he wants to return the fox to the wild, where he belongs. This in itself isn’t a terrible thing to do — modern thinking has it that wild creatures do belong in the wild. But Sara Pennypacker has picked a good moral dilemma — once a wild creature has been tamed, should we then return it to the wild, or are we obliged to keep looking after it?

This is a useful trick for writing parents in children’s literature. Quite often, parents are not ill-intentioned, but they are the opponent nonetheless, because their practical-mindedness abuts the emotional choices of the child character. When the moral dilemma genuinely has two sides to it, like this does, it’s all the more interesting.

Peter isn’t close to his father.

Besides, it wasn’t his father he was missing.

This reminds me of a Leonard Cohen line “like your father or your dog just died“, equating the bond a man can have with a dog on a par with that of his father.

For more on Fathers in Children’s Books, see this post.

Characters Met Along The Journey

Bristle

Meanwhile, Pax comes across a vixen who eyes him suspiciously. Pennypacker (ostensibly Pax) soon gives her a name — Bristle — descriptive of both her hair and her approach to him. Is this a bicker-bicker-kiss-kiss romantic subplot? I wonder this because Bristle is described as ‘bright-furred’ and ‘exotic’, the animal equivalent of commentary on a woman’s sexual appeal. She lets him stay the night, but only one night. In the morning there is a post-coital scene (MG literary animal equivalent thereof) when Pax squirms ‘in pleasure at the solid, warm weight of another’s body nestled against his’. It is therefore funny when Pax wakes up more fully and realises he’s nestled up with the vixen’s brother. ‘Pax pulled himself up sharply’. He was obviously expecting the female fox.

Then her runty brother appears, contrasting in playfulness with her ice-queen demeanour. The Female Maturity Principle kicks in as Bristle cautions Runt on the correct way of behaving around strangers.

Bristle eventually becomes Pax’s mentor, showing him how to hunt. She mirrors the character of Vola in Peter’s journey. Except this one has a romantic component — cheek to cheek they groom each other. I might interpret this as friendship, except you’d never get two male characters sitting like this in a children’s book.

Locals Suspicious Of This Outsider

The setting is peopled with thumbnail characters who exist to show Peter how much of an outsider he is.

First, Peter meets a shop owner who is suspicious of him for not being in school. A woman stares at him and he realises how unkempt he looks.

Later, Peter gazes through a fence (Jon Klassen’s addition) at a boy playing baseball, which brings back all sorts of memories. Peter has visited a therapist, which surprises me a little because I didn’t know the history of therapy was that long in America. Where I come from (New Zealand) therapy was (unfortunately) unknown during the war era. Pennypacker does what a lot of writers do when depicting therapists — apparently this therapist always has the stock standard response. Is this because writers don’t actually know what therapists would say in any given situation? Or is this how it feels to everyone visiting a therapist? That you’re being nodded at? I can’t answer that, but I’m reminded of the recent Liane Moriarty novel/limited TV series Big Little Lies, in which therapists said, “Finally! A realistic fictional depiction of therapy!”

In any case, Peter has a short interaction with a hostile boy who doesn’t like this outsider.

Grey

Pax meets an older male fox whose territory he has inadvertently entered. For all her outward hostility, Bristle has warned Pax about him. Pax calls him Grey. But it turns out this old grey wolf isn’t scary for Pax. (Disturbingly, and off the page, why is Grey scary for Bristle?) Grey turns out to be a false opponent. There’s almost some magical realism — it turns out the crows give messages to this old grey wolf. This is how the author lets us know that war is coming in from the west. This old fox spouts environmentalist messages about the destruction of humankind. It’s mostly an anti-war message.

Peter is confronted by a woman whose barn he is sleeping in. More realistically (not narratively) an adult is far more likely to be kind to a vagrant child they find sleeping in their barn, but this is a mythical journey. This kind of hostile woman plays right into a child’s fears that if they were to go out into the world, every single adult they meet would be the worst examples of human kind. At first meeting, Vola has an inhuman, monstrous quality to her, partly evoked by the wooden leg. However, she does turn into a false opponent-ally, much as the fox has just met. The journeys mirror each other. She helps him with his foot — she happens to have medical knowledge. Like the old grey wolf, this woman has a message about how terrible it is, drafting young people into wars. There are even crows in this scene as there were in Pax’s — their journeys mirror each other’s exactly. Later, Vola turns into a fairy tale witch, offering Peter the tonic with willow bark to act as aspirin. The ‘green paste’ reminds us of witches, too, which is a trope that started with the film adaptation of The Wizard Of Oz. (Before that, they were usually red or orange.)

Eventually, though, Vola is ultimately Peter’s mentor. In a traditional mythic tale, this mentor character is male. Vola is female but apart from plying him with constant food, Vola has masculine traits — her tough attitude, her tool shed. She is a Mr Miyagi character, setting Peter a series of challenges (conditions for staying) to help him grow both spiritually and in skill. Pennypacker isn’t the least subtle about this function for Vola:

“I would have been a good teacher.”

She was right about that. He thought about hwo easily she suggested techniques in his drills without making a bit deal of anything. How she had him watch while she carved, then let him figure out things for himself. How she asked him questions about everything and didn’t answer for him.

Vola

In the initial scene with Vola, Pennypacker shows us an interesting trick MG writers do to first amp up the danger of a situation, then defuse it completely. Peter has thought that Vola might kill him. But then Vola explains that the bladed tools are for wood carving. Vola even lampshades the biases the reader shares along with Peter (since we’re seeing her through Peter’s close third person point of view). There needs to be a name for this — kind of like Chekhov’s gun but a gun which turns out to be a toy gun. Let’s call it Chekhov’s Toy Gun.

In narrative it is dangerous to be a hero’s best friend/sidekick. Grey gets attacked in place of Pax, which would be too hard for readers to bear (tragedy layered upon tragedy) and would also break an unwritten rule of mythic storytelling. The hero doesn’t die at the midpoint of the story. Not normally. When G.R.R. Martin wrote The Red Wedding, he shocked the audience because he was breaking some established norms.

Next Runt dies. These deaths signify just how close to death Pax is himself. At this point I am starting to predict the ending: Clues point to a reuniting at the end, but I’m guessing Pax will be injured. That would symbolise how they’ve both been damaged by this experience and will never be the same again.

I was so lost, I needed to find out all the true things about myself. The little things to the biggest of all: what did I believe in at my core?

Vola

Pennypacker uses the wisdom of children to even up this relationship a little. Vola doesn’t just teach Peter about resilience — Peter challenges Vola for failing to reintegrate into society after coming back from a harrowing war in which she killed a man (Vola’s big ghost). This is a scene you’ll see in Hollywood movies too: the part where friends have an argument in front of the audience, to let the audience in on each of their motivations.

Vola eventually explains that she is part Haitian, part Italian (though if you’d looked up her favourite curse word already you’ve already worked that one out). Her name Vola is Italian for ‘fly’. The trope of comparing women to birds has a long history in literature, though the adult Vola is somewhat unbirdlike — strong and grounded and therefore an ironic moniker. She also doesn’t know how to ‘fly’ — stuck in her cabin with PTSD. For more on the symbolism of flight in literature, see here.

When they get to town, Pennypacker is very obvious about what their outing means for Vola’s character development:

[Peter] looked behind him at the four crude pine creates the marionettes were packed in, strapped to the back. Peter hoped they didn’t remind Vola of coffins. Her amazing puppets were going to live now. Really live, out in the real world, not just exist to perform as some kind of penance.

This is Pennypacker talking about Vola, using her puppets as proxy.

The Coyotes

The coyotes are the mythical monster, not at all anthropomorphised — the evil that descends upon a village threatening friend and foe alike. The coyotes are used for the big big struggle scene in which Peter reunites with Pax.

Other Obstacles Met Along The Journey

Opponents aren’t always human — in a mythical journey a lot of them will be environmental and plain bad luck.

Peter

- The fact that Peter forgot to pack a torch and can’t see in the dark

- Blisters on his heels

- Stepping in cold swamp water because he doesn’t want to risk turning on the torch (an obstacle also used by R.L. Stine in How I Got My Shrunken Head)

- A broken bone in his foot

Pax

- a thunderstorm (this is beautifully written)

- lack of drinking water

- lack of food

- war — the road where he needs to wait has been blocked by war vehicles

IDEOLOGY OF PAX

In Love, Two Characters Become One

The bond between a boy and his canine pet cannot be broken, under any circumstance. A boy’s dog/fox is like the flipside of himself — like a spirit animal — and this bond can be so strong that they are basically the same being. Pennypacker emphasises this time and again, with a near-magical telepathy between Peter and Pax. When Peter confides this telepathy to Vola she doesn’t laugh at him — she congratulates him, telling him how lucky he is. So one message in this story is that if you love someone a real lot, you meld into the same creature. That is true love. This makes Pax a love story, not much different from love stories for adults between two humans.

(Note that love is different from romance.)

War Is Terrible

This runs throughout the book and is not at all novel as an idea in literature. It is the only idea about war running through modern Western literature.

You’re In Charge Of Your Own Destiny

Pennypacker makes use of the symbolism of miniatures with the scenes about the marionette and other puppetry. This is using Peter as god, putting him in charge of his own destiny, which is the reason Vola made him do this task in the first place — he needs to learn to ‘take control of his own life’ rather than letting things happen to him.

Each Person Has A True Self

And it’s just a matter of finding it. This juxtaposes against another psychological theory in which humans are a product of their environment. Rather than there being a ‘one true self’, there are multiple versions of the self. We change according to circumstance, and we change a lot more over the course of our lifetimes than we realise, moulded by our particular circumstances. This latter view is the more popular in modern psychology, but literary, classic-sounding children’s books such as this one are more inclined to stick with the older view.

For more on the concept of the one true self, and how Western literature goes with that view see: The Ideology Of Individuality And Social Norms In Children’s Stories

CHAPTER ENDINGS

Take a look at any Goosebumps novel and you’ll see each chapter ends in an obvious cliffhanger. In a literary novel like this one, the cliffhangers are not so obvious but they’re there all the same, making the reader anxious for the characters’ safety. For instance, Chapter 31 ends with the non-climactic sounding ‘He turned back for the clearing’. But the reader knows that Pax is in danger of being shot even though Pax doesn’t realise this himself. The cliffhanger is there but more subtle. And it requires a little work on the part of the reader.

THE ENDING

I was slightly wrong about the ending — Pax himself is physically well — it’s his replacement, Bristle, who has the big bleeding gash and the missing leg.

Which leads to another ideological concern, as explained by this Goodreads reviewer:

[I WANTED PETER TO GET HIS FREAKING FOX BACK. But no. He decides Pax is better off in the wild and instead Peter takes home Runt to care for him since Runt got his back legs blown off. But I. am. so. mad. It’s like saying that a bond between pet-and-human is replaceable. WHEN IT’S NOT. I would lose a piece of my soul if my precious pup died or got lost or just wasn’t there for me anymore. So all I can think of is losing my dog as Peter lost Pax for the 2nd time at the end of the book. AND IT’S NOT OKAY. It wasn’t one of those “bittersweet” endings. It downright BROKE ME and I’m not okay. Sure Pax didn’t die (small miracles) but he kind of died in my heart and I don’t I don’t I don’t like this. I FEEL LIKE CRYING.

Paper Fury

There are many picture books in which a dog dies and the story ends with a kid getting a new one. These are not considered the best of the best of the Dead Dog books. I’m not sure why the same ending is so well accepted in this case. Perhaps because Pennypacker isn’t obvious about what happened. At first I wondered which dog was which. Or perhaps we accept this story because in general it’s very well written.

Here’s Sara Pennypacker talking to School Library Journal about writing the ending. As in many children’s books, mirroring the end with the beginning affords readers a sense of closure. Bear in mind, there are two types of closure.

It does something else, too — it gives some circularity to what is otherwise a very linear story. This boy is going to bond with this other animal and the cycle will continue, over and over, throughout the ages.

The ending was set early on. I was walking in the woods, and it just came to me in a bolt: the ending image needed to be the same as the image that set the plot in motion—although it would have a completely different meaning for both Pax and Peter the second time and would show how each character had grown.

SLJ

But because Pax has Bristle, this is a happy ending love story for Pax.