Let’s say there are 7 main categories of Narrative art. Narrative art is art which tells a story.

- Monoscenic — represents a single scene with no repetition of characters and only one action taking place

- Sequential — very much like a continuous narrative with one major difference. The artist makes use of frames. Each frame is a particular scene during a particular moment. Think comic strips.

- Continuous — Continuous narrative art gives clues, provided by the layout itself, about a sequence. Sequential narrative without the frames.

- Synoptic — offers the synopsis of a bigger story. You must know a story before you can understand synoptic narrative.

- Simultaneous — has very little visually discernible organisation unless the viewer is acquainted with its purpose. There’s an emphasis on repeatable patterns.

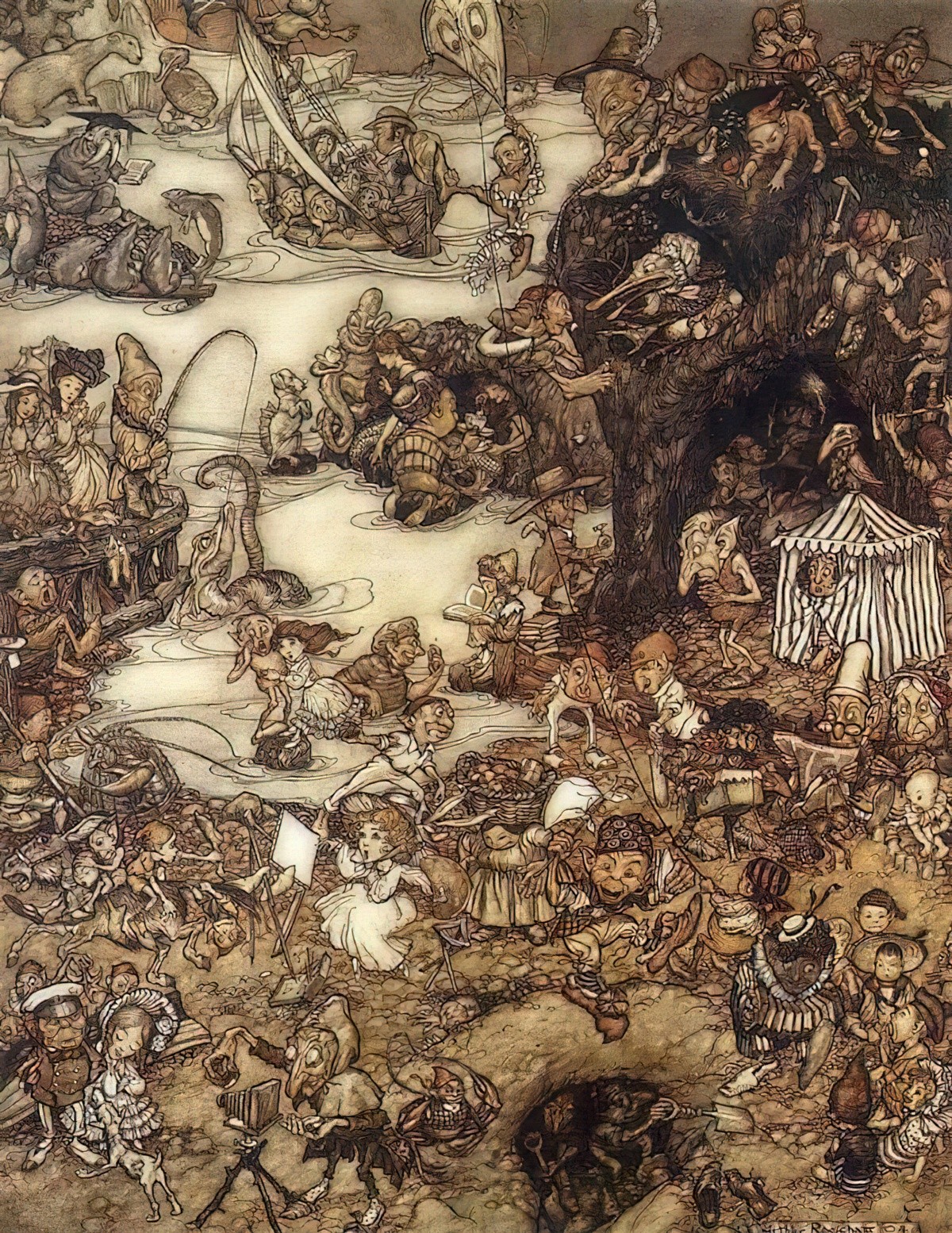

- Panoptic — depicts multiple scenes and actions without the repetition of characters. Think of the word ‘panorama’. ‘All-seeing’ (pan + optic)

- Progressive — a single scene in which characters do not repeat. However, multiple actions are taking place in order to convey a passing of time in the narrative. A progressive narrative is not to be interpreted as a group of simultaneous events but rather a sequence that is dependent on its positioning on the page. Actions displayed by characters in the narratives compact present and future action into a single image.

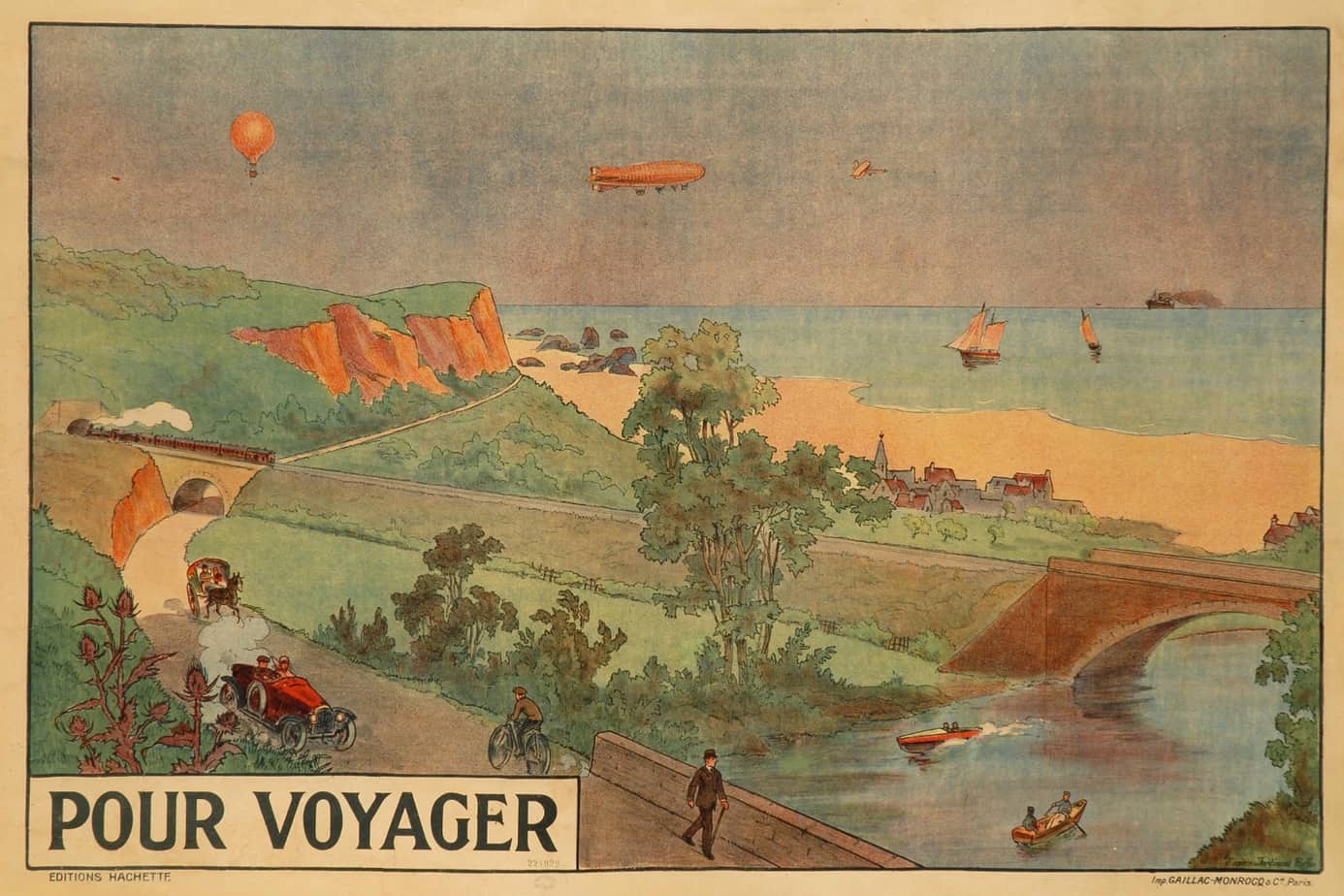

Panoptic refers to ‘showing or seeing the whole at one view’. Panoptic narrative art is often a bird’s eye view. The ‘camera’ is above. This is the art world’s equivalent of an all-seeing (omniscient) narrator.

Panoptic and panoramic art was popular in the medieval era, where it most often depicts a myth.

(The term has nothing to do with Foucault’s panopticism — I believe the word is made up of ‘pan’ + ‘optics’ as in ‘all-seeing’.)

You will also hear the term ‘panoramic narrative’. This describes a narrative image that depicts multiple scenes and actions without the repetition of characters. Actions may be in a sequence or represent simultaneous actions during an event. Whereas the word ‘panoptic’ is generally used to describe aerial views, ‘panoramic’ is used to describe a ‘camera’ closer to the ground.

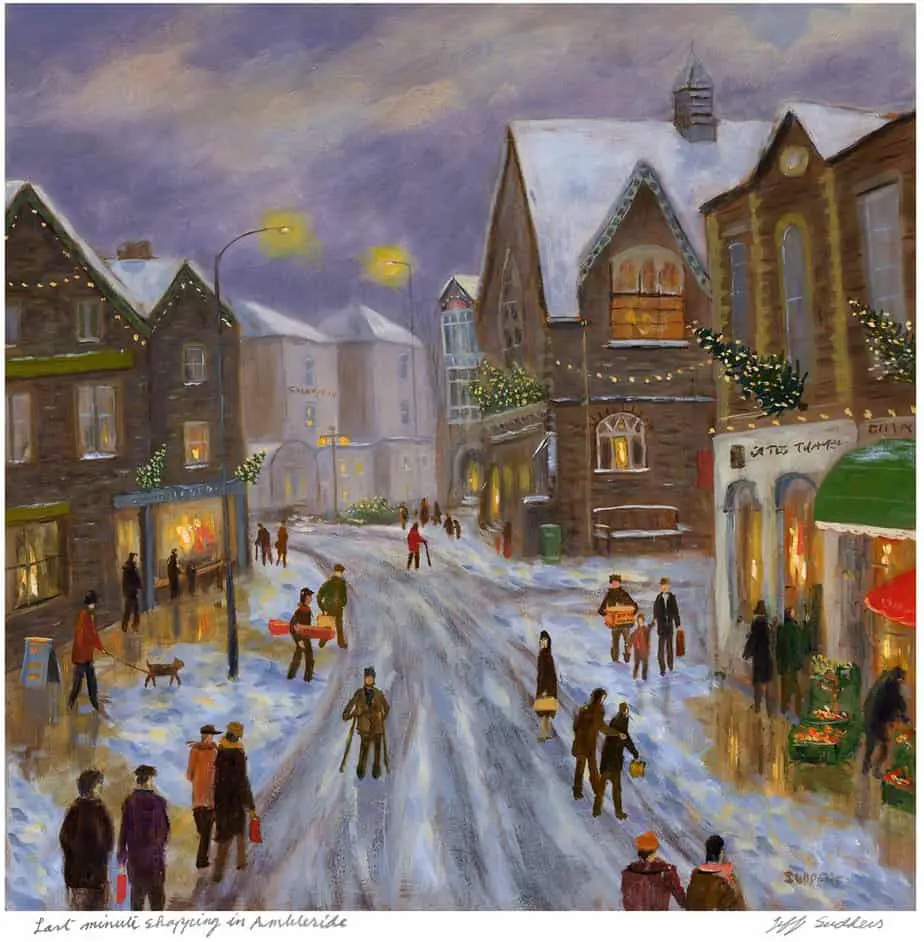

Take a look at two similar scenes below: Christmas shopping on a cosy winter street. Though the subject matter is similar, I interpret them differently. The painting by Kevin Walsh seems to me an amalgamation of various things that have happened on the street that day. I don’t really think those people are all on the street together at the same time.

In contrast, this Jeff Sudders painting looks like a realistic snapshot of a scene full of shoppers. I read this one differently: All of the shoppers depicted are there at the same time.

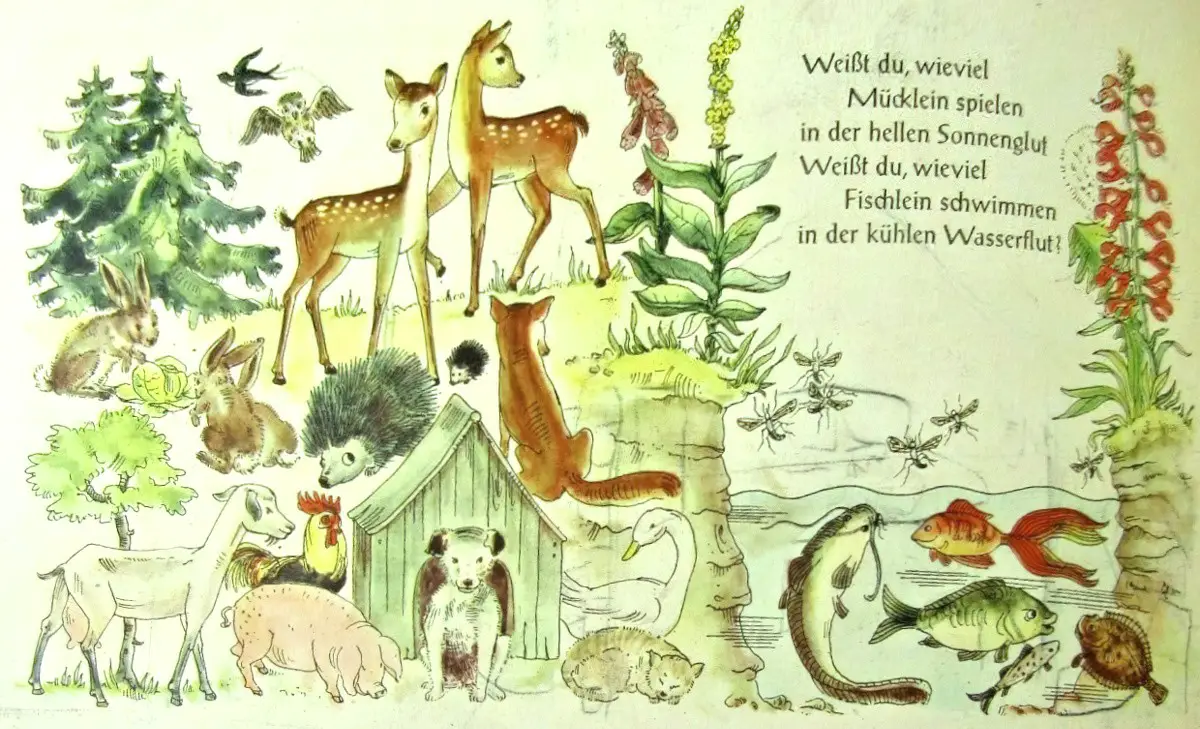

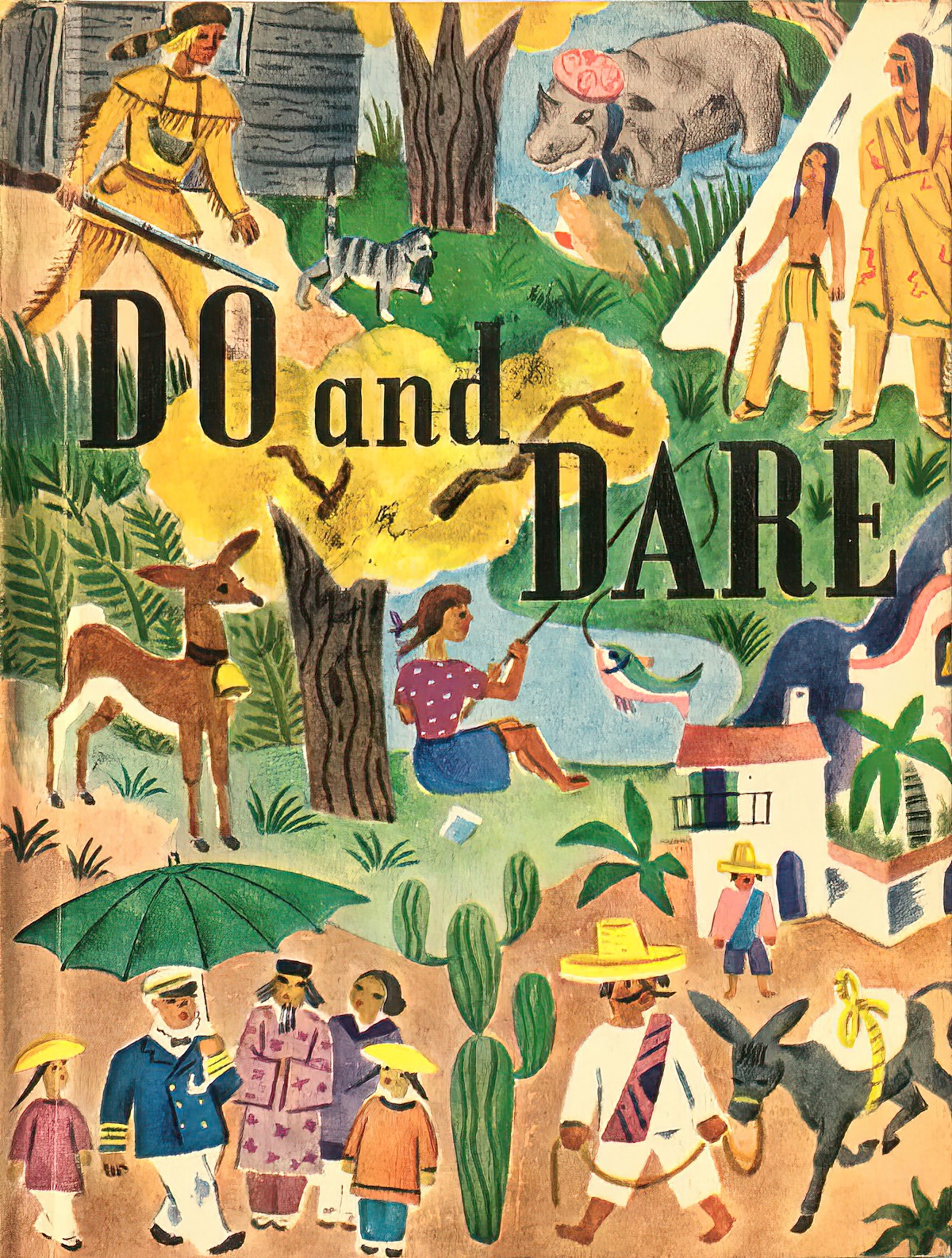

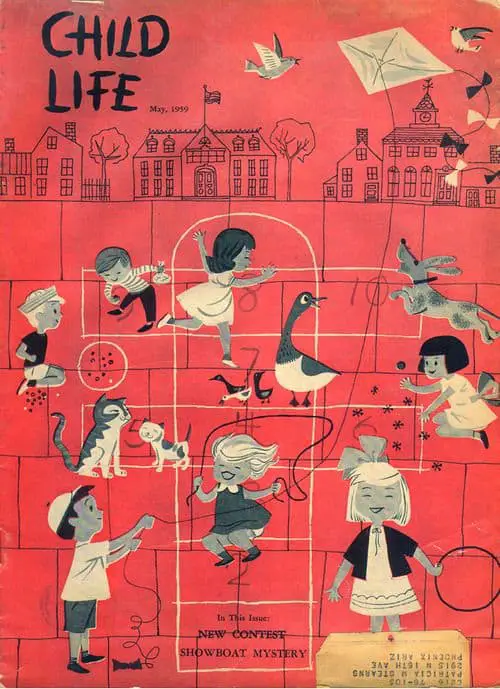

Do and Dare 1965

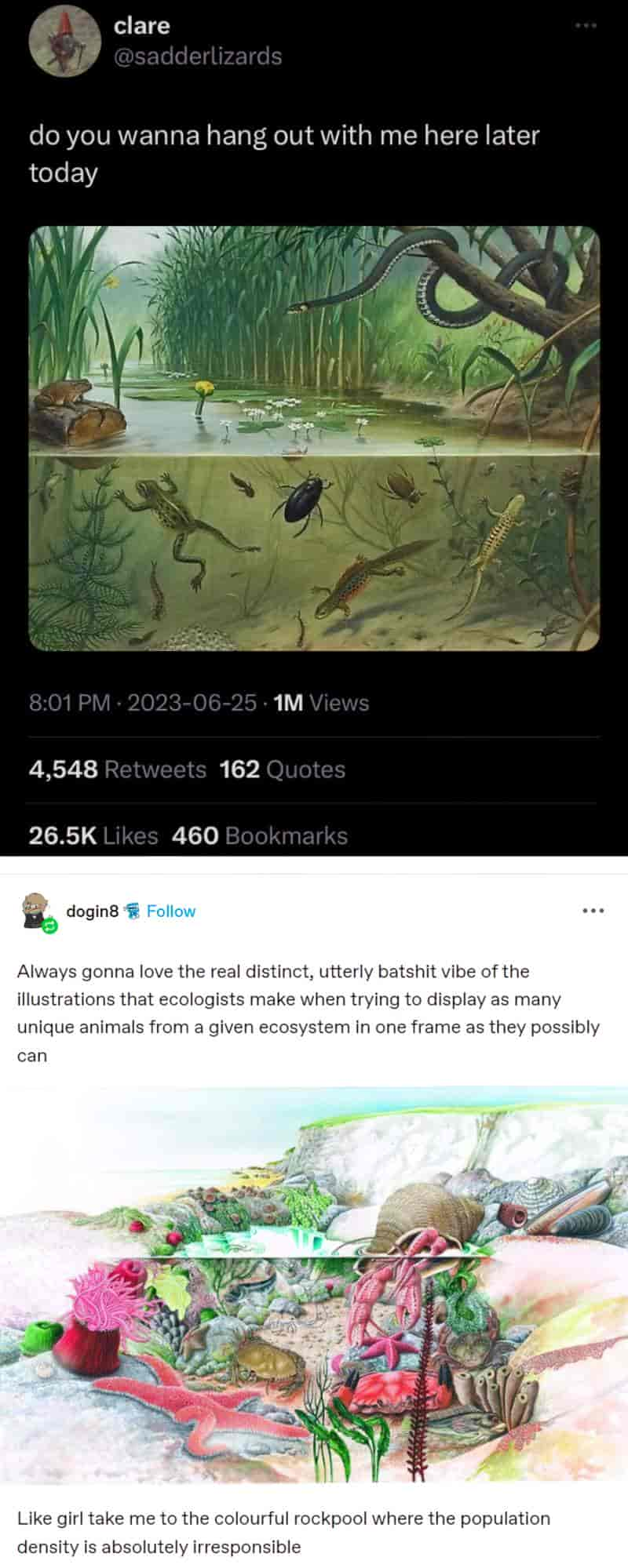

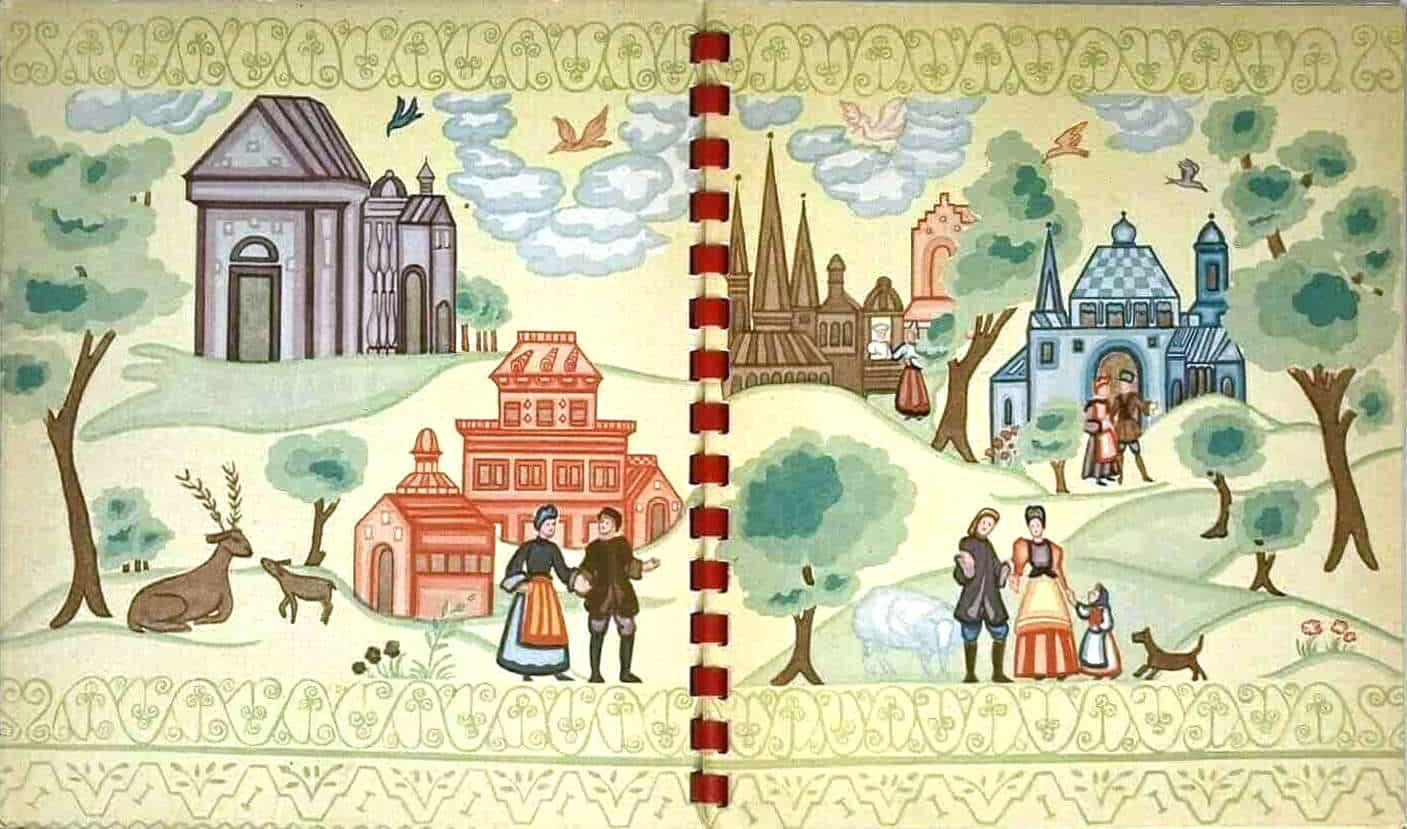

Below are some examples of the folk art style, which works very well for panoptic imagery.

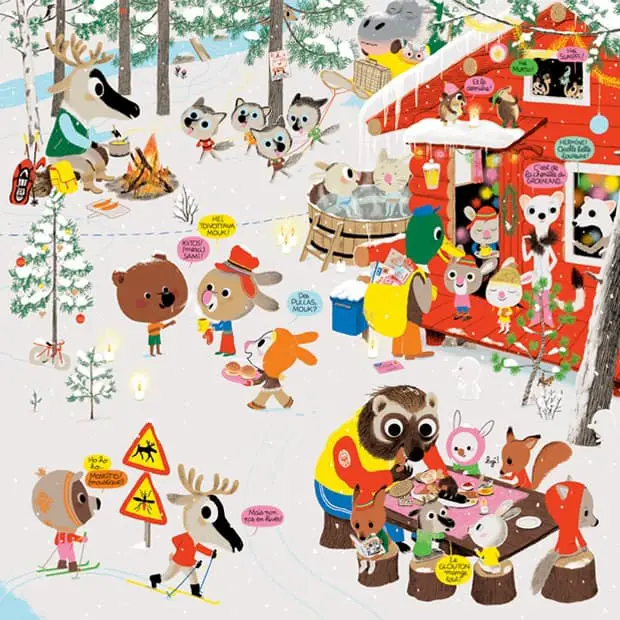

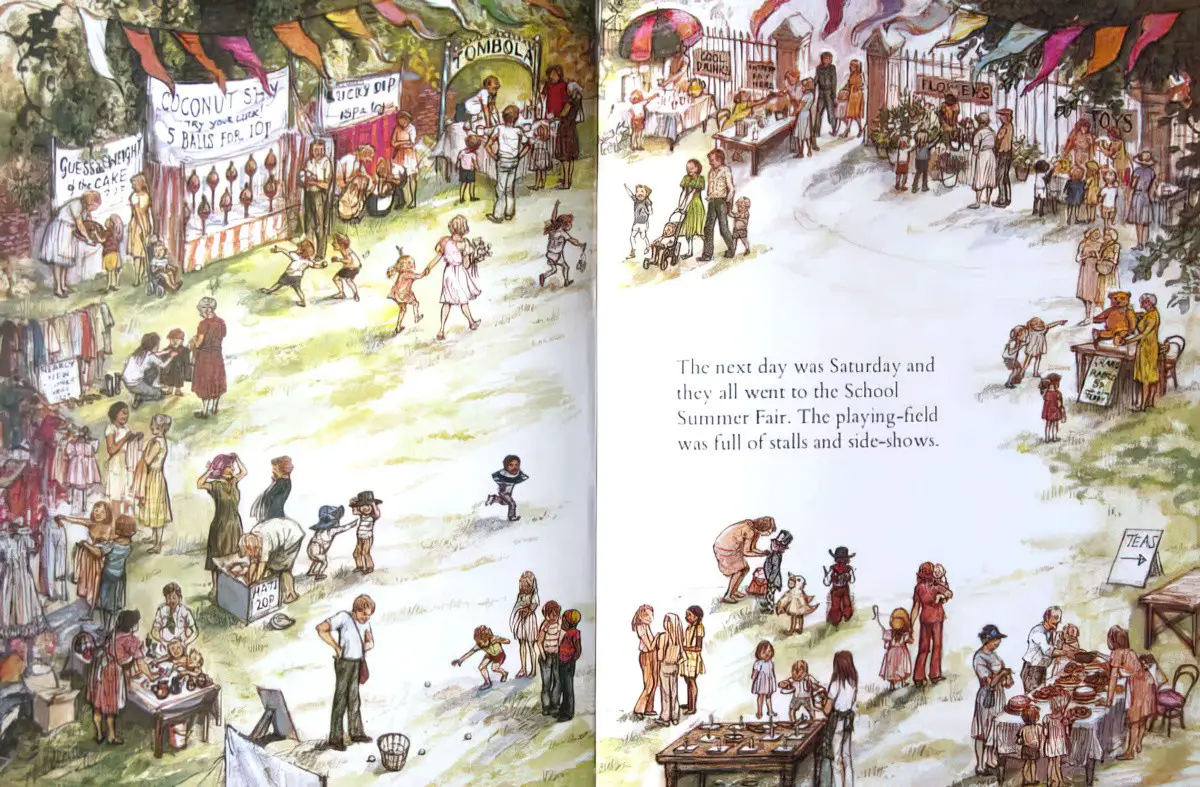

In modern picture books, there is a gradation of activity in a scene. Often, there is way more going on in a single picture book illustration than would ever be happening in a real life photograph. For example, in the scene of the school fair from Shirley Hughes’s Dogger, below, we can see sorts of things going on — all of which would have happened at the fair — but all of the individual actions are meaningful and it’s unlikely they were all going on at the same time. The work is therefore on the panoptic continuum.

Film makers, too, often need to arrange characters within scenes in a way that wouldn’t naturally occur. But we accept these film conventions to a large degree, even when realism is the aim.

What if it’s clear from the context of the story that multiple actions in a single scene are definitely not going on at the same time? This is called Progressive narrative art, in which actions displayed by characters compact present and future action into a single image.

I believe Progressive narrative art is a subcategory of Panoptic art, and in picture books and film the two terms merge, for the simple fact that we in stories, characters live in ‘storybook worlds’, in which it’s perfectly possible all of these things are going on at once. We can’t possibly distinguish between the two states unless we were to know the ‘real events’. But these aren’t wars we’re describing — they are made up from the get-go; there is no basic ‘reality’.

Roland Harvey

Australian artist Roland Harvey is an expert at busy, detailed landscapes and has created a whole series of books with massive panoptic scenes: In The Bush, At The Beach, In The City and panoptic scenes occurring throughout his others.

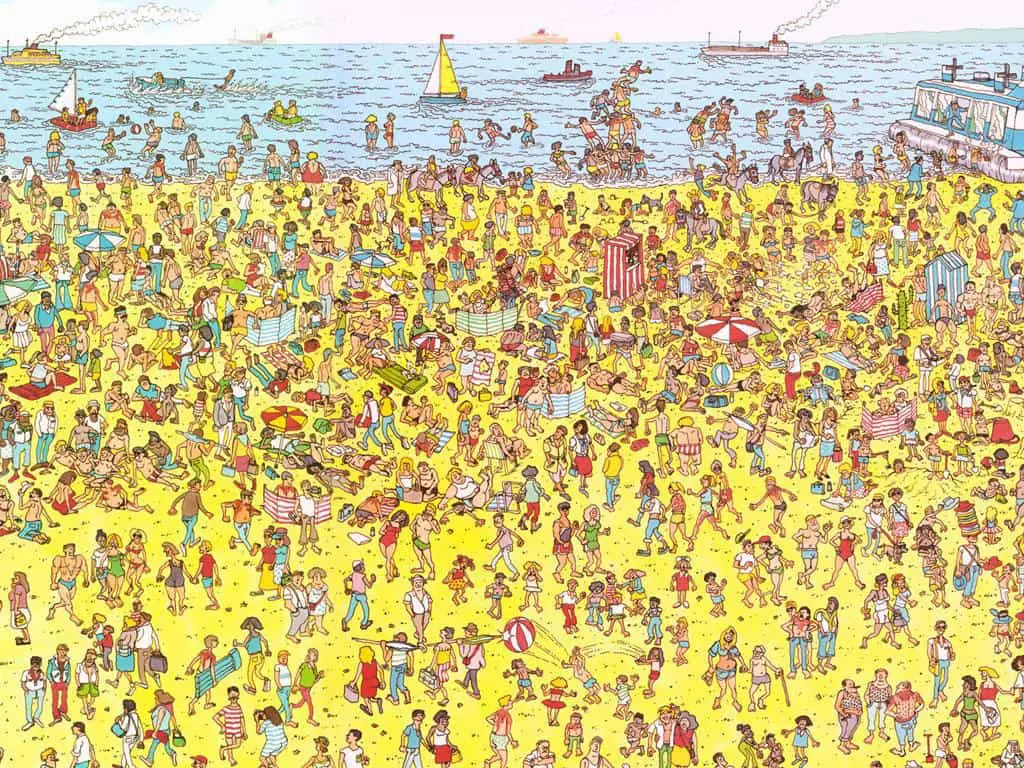

Where’s Wally/Waldo

Where’s Wally was created by Martin Handford, English illustrator. These books make the most of that wish to hunt and search, linger and examine.

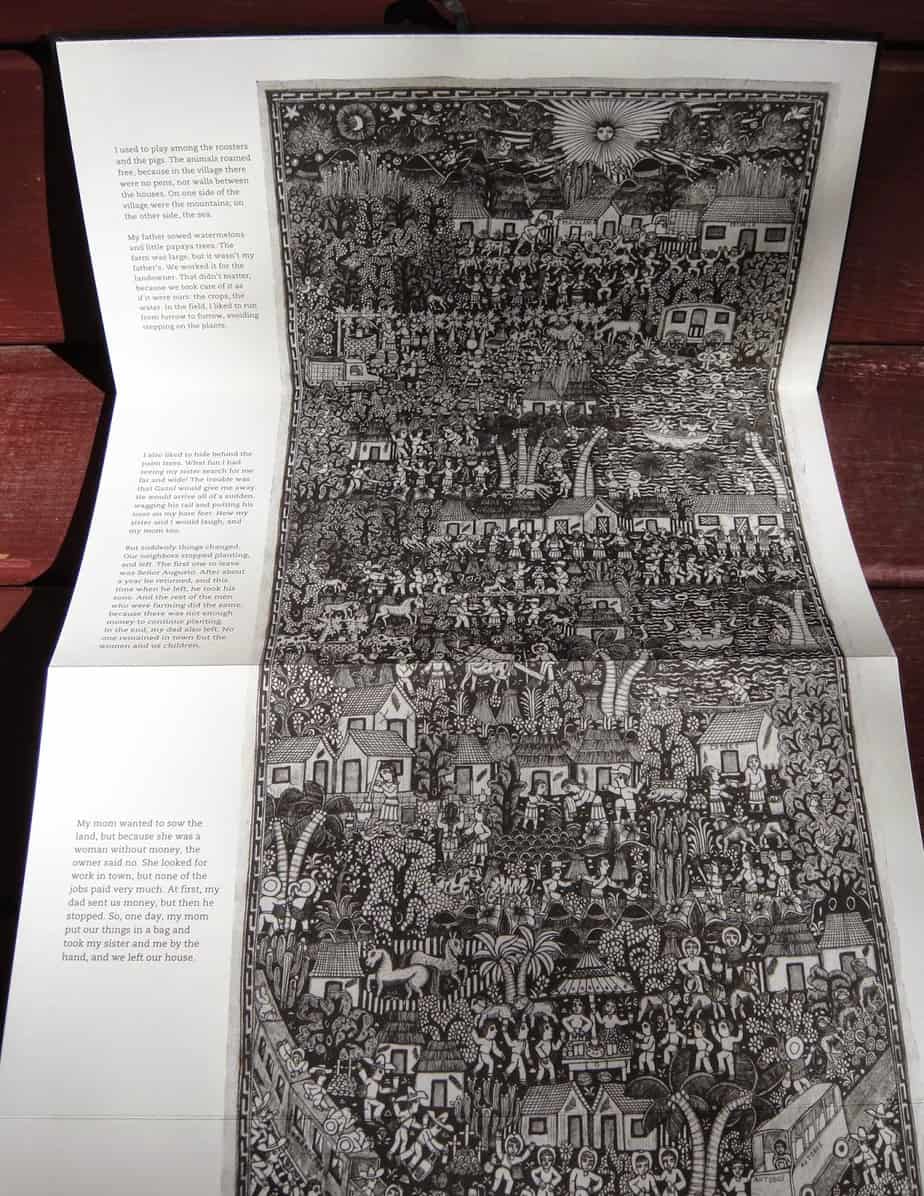

Migrant by Jose Manuel Mateo

This book uses a single vertical illustration and brief text. It folds up accordion-style and recounts the story of a young family who immigrate illegally to Los Angeles, one huge image that is slowly unveiled over the course of the story.

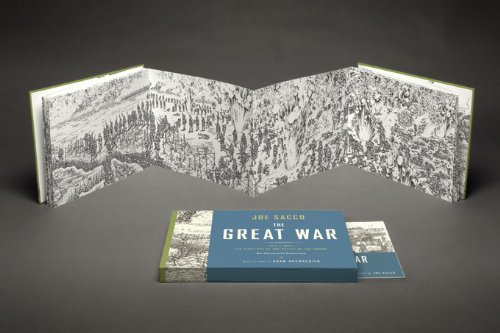

The Great War : July 1, 1916 : the first day of the Battle of the Somme

Header: Life in the Sky John Leigh-Pemberton (1911–1997)