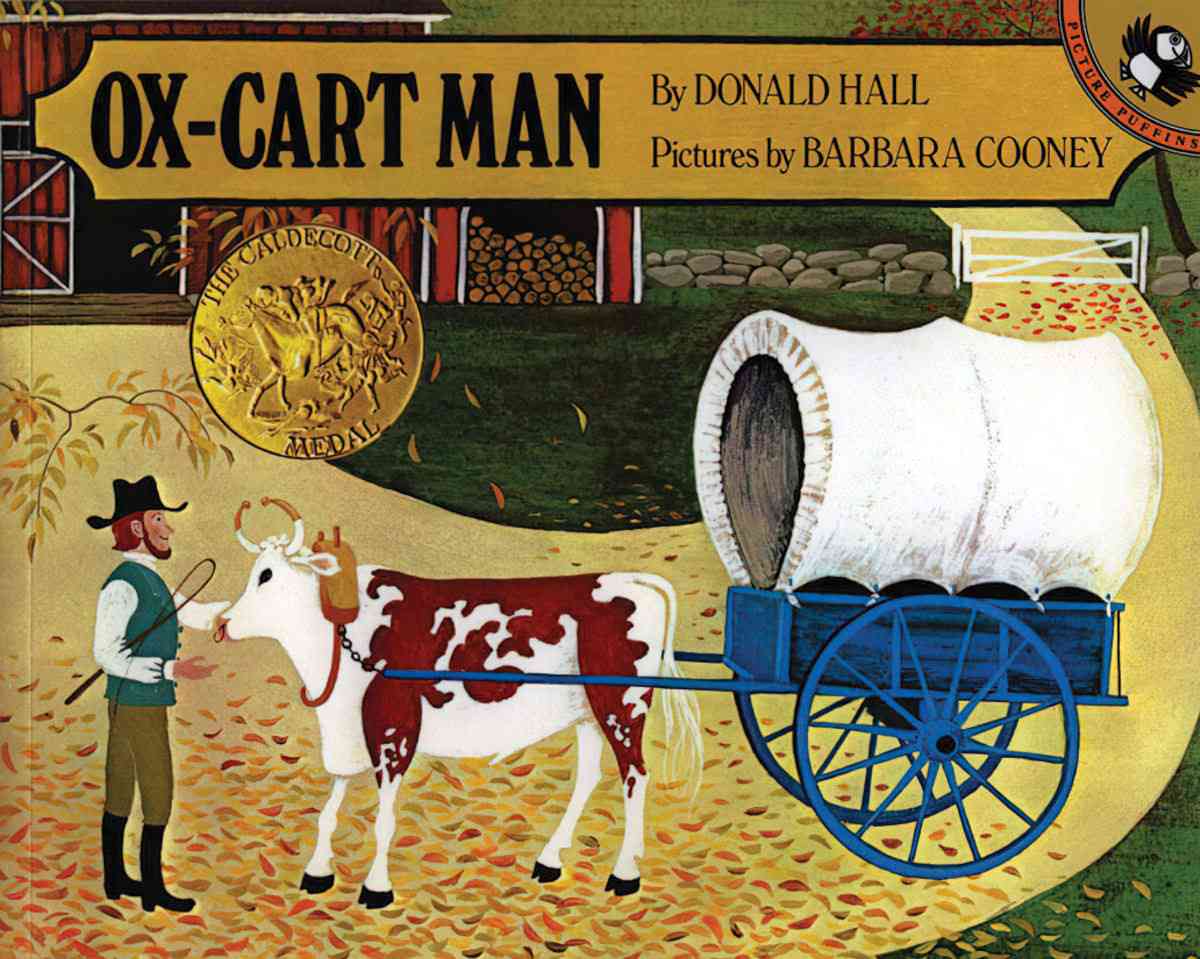

Ox-Cart Man is an American picture book written by Donald Hall and illustrated by Barbara Cooney in 1979. The following year, in 1980, it won the Caldecott medal. In this post I compare the prose of “Ox-Cart Man” to the writing style of Cormac McCarthy, express my love for cosy stories like these while acknowledging their slightly problematic ideology.

PARATEXT

Winner of the Caldecott Medal

Thus begins a lyrical journey through the days and weeks, the months, and the changing seasons in the life of one New Englander and his family. The oxcart man packs his goods – the wool from his sheep, the shawl his wife made, the mittens his daughter knitted, and the linen they wove. He packs the birch brooms his son carved, and even a bag of goose feathers from the barnyard geese.

He travels over hills, through valleys, by streams, past farms and villages. At Portsmouth Market he sells his goods, one by one – even his beloved ox. Then, with his pockets full of coins, he wanders through the market, buying provisions for his family, and returns to his home. And the cycle begins again.

marketing copy

Like a pastoral symphony translated into picture book format, the stunning combination of text and illustrations recreates the mood of 19th-century rural New England.

The Horn Book

THE RHYTHM OF PROSE: A COMPARISON TO CORMAC MCCARTHY

“Ox-Cart Man” begins:

In October he backed his ox into his cart

“Ox-Cart Man”

and he and his family filled it up

with everything they made or grew all year long

that was left over

Does that sound a little… Cormac-McCarthy to you?

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him.

opening sentence to The Road by Cormac McCarthy

I’ve heard it said that McCarthy’s prose is ‘metred’. This is sometimes brought up to explain why McCarthy, alone, gets away with randomised apostrophes and, at times, metaphor which stretches the most generous of imaginations. (Btw, his prose is not metred, but nor is it arrhythmic. Same goes for many picture books, including “Ox-Cart Man”.)

People have written papers specifically on the scansion of Cormac McCarthy:

Does it matter that a novel’s first fifteen syllables slip into lilting triplets, and that the next three do not? McCarthy could so easily have continued that lilt by expanding his contraction — “in the dark and the cold of the night he would reach out to touch” — but instead that regular pulse is interrupted. Or perhaps the syllables syncopate over a beat.

Sean Pryor, UNSW, 2012, Styles of Extinction: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, who points out further down that the rhythm of the opening echoes the breathing of the sleeping man and boy.

As McCarthy’s opening paragraph progresses, Sean Pryor notices how

McCarthy overlays syllabic with syntactic rhythms. Pairs of strong stresses portion out those first two phrases, each of which concludes with a prepositional qualification: “Tolling in the silence”, “the minutes of the earth”. A triple rhythm shapes the next pair of stresses, aligned by a common prepositional phrase: “and the hours and the days of it”. And then that polysyndeton compels yet another pair in triplets: “and the years without cease”. This complex rhythm structures the sentence’s steady expansion from single drops, through minutes, hours, days, and years, to eternity. If the earlier sentence linked McCarthy’s writing to biology, this sentence links it to the order of the solar system.

Sean Pryor, UNSW, 2012, Styles of Extinction: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road

Yep, type to bust out the M.H. Abrams.

Polysyndeton: multiple repetitions of the same conjunction (and, but, if, etc), most commonly the word “and.” Polysyndeton can be used (as it is in The Road) to convey a flat, mechanical routine and the marching-on of time, regardless of what humans do. It can also do the opposite, if the clauses are short and the action exciting.

Writers who grew up reading The Book of Mormon sometimes have a natural tendency to begin many sentences with ‘and’. Check out The Book of Mormon and you’ll immediately see why.

(Let it be noted, Cormac McCarthy comes from a Catholic background. James Wood reckons when people call McCarthy’s prose ‘biblical’ what they really mean is ‘antiquarian’.)

Other useful words from the paper which might also be used to talk about “Ox-Cart Man” (and what it is not):

Euphony: describes language pleasing to the ear

Hypotaxis: the subordination of one clause to another (cf. parataxis)

Narrative ostinato: In music, an ostinato is a motif or phrase that persistently repeats in the same musical voice, frequently in the same pitch. “He packed a bag of wool… He packed a shawl his wife wove… He packed five pairs of mittens…”

Parataxis: when independent phrases are placed side-by-side without conjunctions. (cf. hypotaxis)

Privative: expressing absence or negation, for example the Greek a-, meaning ‘not’, in atypical. Saying what something is not. In McCarthy’s case:

Then a distant low rumble. Not thunder. You could feel it under your feet. A sound without cognate and so without description.

Use of privative in The Road

Below is the entire first paragraph from The Road. Do you feel the rhythm of the breathing and the sense of universal relevance? As Pryor explains further down, it’s all about matching and mimesis: heartbeats, breaths, waking and sleeping, day and night, safety and danger, food and hunger, travel and rest, action and thought, question and answer, speech and silence, life and death:

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world. His hand rose and fell softly with each precious breath. He pushed away the plastic tarpaulin and raised himself in the stinking robes and blankets and looked toward the east for any light but there was none. In the dream from which he’d wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Their light playing over the wet flowstone walls. Like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast. Deep stone flues where the water dripped and sang. Tolling in the silence the minutes of the earth and the hours and the days of it and the years without cease. Until they stood in a great stone room where lay a black and ancient lake. And on the far shore a creature that raised its dripping mouth from the rimstone pool and stared into the light with eyes dead white and sightless as the eggs of spiders. It swung its head low over the water as if to take the scent of what it could not see. Crouching there pale and naked and translucent, its alabaster bones cast up in shadow on the rocks behind it. Its bowels, its beating heart. The brain that pulsed in a dull glass bell. It swung its head from side to side and then gave out a low moan and turned and lurched away and loped soundlessly into the dark. With the first gray light he rose and left the boy sleeping and walked out to the road and squatted and studied the country to the south. Barren, silent, godless. He thought the month was October but he wasnt sure. He hadnt kept a calendar for years. They were moving south. There’d be no surviving another winter here. When it was light enough to use the binoculars he glassed the valley below. Everything paling away into the murk. The soft ash blowing in loose swirls over the blacktop. He studied what he could see. The segments of road down there among the dead trees. Looking for anything of color. Any movement. Any trace of standing smoke. He lowered the glasses and pulled down the cotton mask from his face and wiped his nose on the back of his

Cormac McCarthy, The Road, full opening paragraph

wrist and then glassed the country again. Then he just sat there holding the binoculars and watching the ashen daylight congeal over the land. He knew only that the child was his warrant. He said: If he is not the word of God God never spoke.

But why am I reminded of Cormac McCarthy when reading a 1979 picture book? (See what I did there?)

The similarities jumped out when I encountered that last line of the first page of “Ox-Cart Man”, because I would never have thought to write such a line myself: that was left over.

With that final clause, the entire sentence changes from being an easily digested flat structure to one which now requires readers to remember the beginning before understanding the end.

If you’re interested in how written sentence lengths have shortened over the 20th century, Language Log has a good post on it:

A couple of days ago, The Telegraph quoted an actor and a television producer emitting typically brainless “Kids Today” plaints about how modern modes of communication, especially Twitter, are degrading the English language, so that “the sentence with more than one clause is a problem for us”, and “words are getting shortened”. I spent a few minutes fact-checking this foolishness, or at least the word-length bit of it — but some readers may have misinterpreted my post as arguing against the view that there are any on-going changes in English prose style.

Language Log, way back in 2011. (If Twitter really has much to do with things, sentence lengths should’ve got much shorter in the decade since.)

Basically, there are long sentences and then there are long sentences which are complicated to read. Two completely different things.

As in Genesis, we might say there’s a “biblical feel” to both The Road and to “Ox-Cart Man”:

While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.

Genesis 8.22

Worth noting: The calming, Biblical rhythm of The Road is ironic. McCarthy’s setting is a forsaken one.

Not so in the picture book, however! You’ll find good, strong, Protestant work ethic in this one. If you work hard, the earth shall reward you. That’s the basic message and it is an extremely alluring one.

Listen to: God Wants You To Be Rich from NPR’s Throughline for a good explanation of the Protestant work ethic and what it has morphed into in today’s America.

Critical though I may be, I succumb to that wonderful delusion of self-sufficiency when I’m outside collecting sticks for the fire. I think, “You know what? If the zombie apocalypse hit this afternoon, at least we’d have kindling.” Then I burn through those sticks in ten minutes. I also get that feeling from keeping backyard chickens. This gets real grim real quick: “If the zombie apocalypse hits tomorrow, at least we’ll have chicken meat. And eggs. Well, you can’t have your chicken meat and egg, too. And we’d need a rooster at some point to keep the whole chain going. I’d have to ask a favour of those neighbours with the rooster. Maybe I shouldn’t be so hard on them for getting a noisy rooster.”

I have previously confessed my weak spot for self-sufficiency wish-fulfilment stories, and confessed that of all the reality TV shows I might find myself on, it would most likely be Preppers, despite the reality I’m anti-gun, don’t live rurally and am far from amassing a stockpile of food. Nay, this household is regularly out of at least one necessary grocery item per week due to non-reliance upon a grocery list. My wish to not become a Prepper, when I’m one 3am-newscycle away from succumbing, means I’m at the point where, if worst comes to worst, I’d prefer to just die. Justine from Melancholia is my spiritual guide. (Who wants to share a scorched earth with Prepper types anyway? Let em have the joint.)

However! If you just watched Melancholia, or Doubt, or August: Osage County and are feeling a bit down about the world and its workings, “Ox-Cart Man” is the bibliotherapy for you. Nothing but self-sufficiency fantasy here. (Note: self-sufficiency is a fantasy. We are all interconnected. Always was a fantasy, but has only gotten more so since the pilgrim era, and even since the late seventies, since this book was published.)

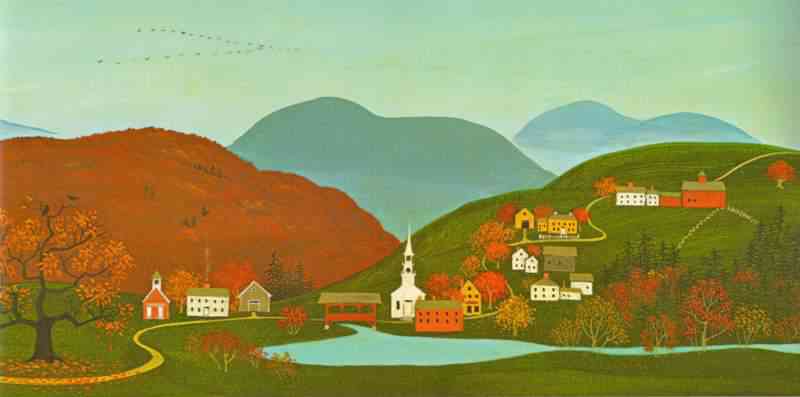

SETTING OF “OX-CART MAN”

New England! America! Nineteenth century white settlers!

A fit, able-bodied nuclear family with a pigeon-pair of helpful children, complaining about nothing, working from dusk til dawn to keep themselves alive. And because they work hard, they can justify claim on the stolen land, feeling God gave it to them as reward, I bet.

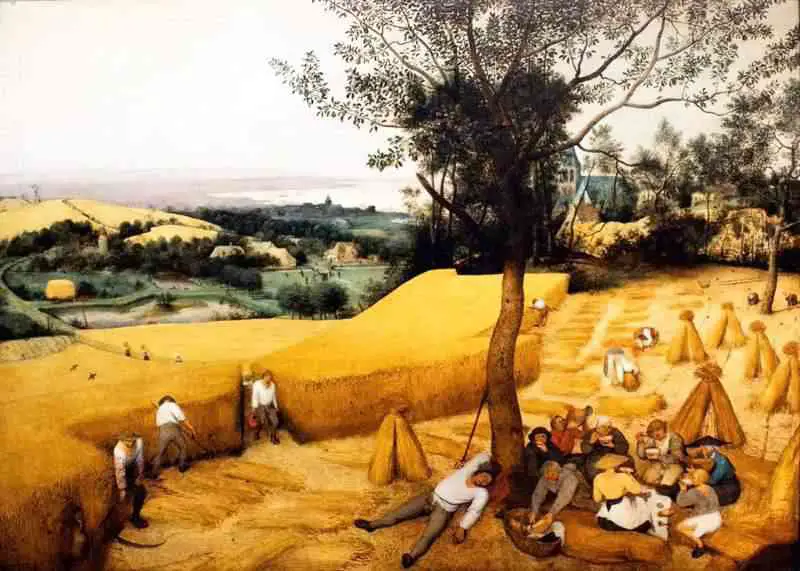

Barbara Cooney’s illustrations are a perfect fit for this super-cosy story. Take a look at this one. Remind you of anything?

Bruegel the Elder, perhaps?

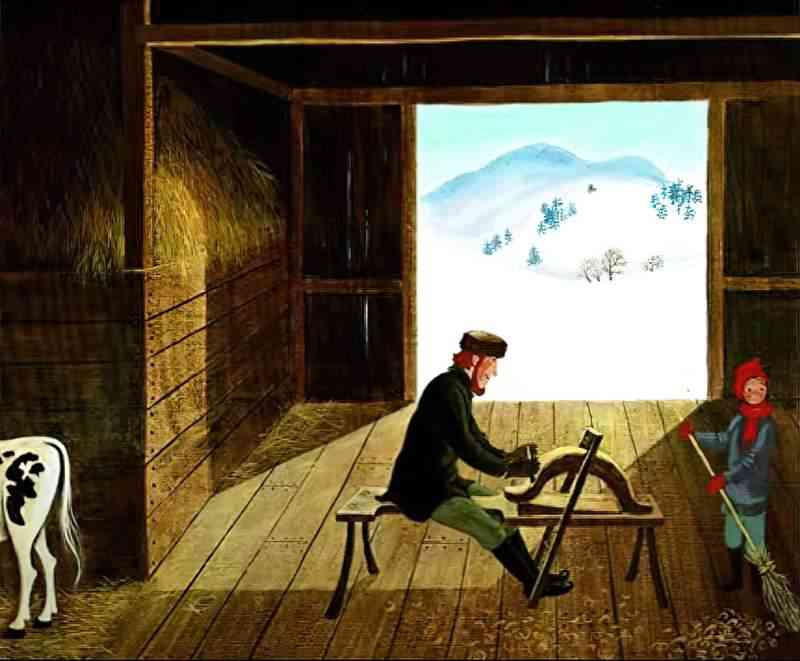

Here’s the recto side of an autumn spread as the father makes his ten-day trek into Portsmouth to sell all the stuff the family has made over winter. This picture book is circular, shaped by the seasons. We are told time and time again that March is the season for preparation, though every season has its tasks.

What Sean Pryor says about The Road also applies in “Ox-Cart Man”, ah, minus the cataclysmic bits:

The rhythm of words suggests the movement of the cosmos. But how can a novel link its language to the rhythms of a single narrative, to the biological rhythms that sustain human life, and to the celestial rhythms of slowly turning planets? How can it do that and so ostentatiously lament the transformation of language occasioned by a single cataclysm? For though that cataclysm dictates McCarthy’s narrative, though it has ended the migratory cycles of birds, and though it might yet snuff out human life, it leaves the constant cosmos unaffected. If there were still a crow to fly above the thick ashen clouds, the man explains, it would find the sun going about its usual business.

Sean Pryor, UNSW, 2012, Styles of Extinction: Cormac McCarthy’s The Road

How does “Ox-Cart Man” achieve that sublime, overview effect, which Pryor calls ‘cosmological’?

- Birds are always good for that, requiring us to contemplate the sky.

- Beautiful cinematic views of the landscape

- Juxtapositions between seasons

- And also day and night (the return journey home is a night scene).

Speaking of byrds:

And how does Cormac McCarthy convey the breathing, cyclical nature of the universe in his novel The Road? By alternating long and short sentences. Pryor uses the term “narrative dyastole”, meaning the phase of the heartbeat when the heart muscle relaxes and allows the chambers to fill with blood.

Can you see this “narrative dyastole” in the language of “Ox-Cart Man”?

Alongside lengthy sentences of the sort which opens the text, we have a staccato of short sentences of the sort early readers can cope with:

He sold the bag of wool.

He sold the shawl his wife made.

He sold five pairs of mittens.

He sold candles and shingles.

He sold birch brooms.

He sold potatoes.

He sold apples.

He sold honey and honeycombs,

turnips and cabbages.He sold maple sugar.

He sold a bag of goose feathers.

“Ox-Cart Man”

The work involved in creating all these things is immense. Therefore those sentences are long. But when you sell your produce, the hard work is gone in an instant. Sentences are short. The narrative diastole of “Ox-Cart Man” mimics this truism. (Hence: “mimesis”.) Naturally, when the man walks all the way home (which takes ten days by foot) the sentence lengthens to match.

Can young readers cope with long sentences? They can, but only if the grammatical structure is ‘flat’. These are short sentences joined with conjunctions. Clauses embedded within clauses are a different matter. (See the Language Log post on sentence length for more on that.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF “OX-CART MAN”

SHORTCOMING

The Man has no name. He is Universal Man. Note that Universal Man is a manly (settler) man with a wife and children.

Did you notice how the man in The Road also has no name? That’s for a different reason:

In a melodramatic moment, the man thinks of the post-apocalyptic transformation of language as the death of names: “The names of things slowly following those things into oblivious”. Blue no longer refers to a colour, or to the sky, or to the sea.

Sean Pryor

This isn’t your typical character-has-a-shortcoming, makes plans, plans get foiled, comes near death, realises something sort of story. The family is a model of human behaviour, according to a certain worldview. Characters act like settler automatons, and everything they do pays off.

So instead of analysing this story in terms of the fictional characters, I’ll focus on the narratees — us!

DESIRE

What do people want? We want to believe this is what pioneer life looked like. We like to think this is how the world works: We give, the universe provides in kind.

In autumn we’d like to pack our cart with all our surplus harvest and home made goods. We’d like the man of the family to make the arduous journey in to town. We’d like him to sell his wares, his cart and the ox that pulls it. We love that he kisses the ox goodbye. Stories work best when they include a tender moment such as this. The more universalised the story, the more important such moments become.

Wintergreen mints are a nice touch, especially for people who know what those are, I bet.

Alongside the alternative view of Cormac McCarthy, I might direct you to the anti-Western short stories of Annie Proulx, in which white people move to the wilderness nursing some notion of rugged self-sufficiency, becoming one with the land and all that, and then die. (Proulx’s “Wyoming stories” are modern examples of the settler experience.)

OPPONENT

There’s no traditional opponent in this cosy-mythic journey because the universe provides.

But we are told every good story requires opposition. Is this really true, then?

A story requires opposition, or it requires some kind of mystery. This isn’t exactly a “mystery story” per se but young readers are left hanging about the reason for getting rid of everything including the ox. The part where the father kisses his trusty animal on the nose elicits pathos. This ox has been integral to his life. And we have no idea why he’s selling it, really. It helps when an act of kindness is unexpected, too. We didn’t anticipate a man would kiss an ox on the nose. This makes it sadder.

PLAN

Do we ever find out the reason for selling the ox? We deduce. The man must sell the ox to buy supplies to tide the family over winter. There may be a few baby oxen waiting at home on the farm, too, ready to till the fields next season.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The father sells absolutely everything he is carrying until he is left with the clothes on his back. Then he starts on his buying spree. Being left with nothing is as close to spiritual death as this story comes, and appeals to the aesthete in us all.

Speaking of narrative diastole, there’s a diastole that goes along with my own urge to collect and purge. I suspect this is common to many of us: My desire to own bookshelves of books coexists with my urge to pare my home library down to only my favourite volumes. Collect, purge, collect, purge. (Okay, mostly collect.)

The shopping spree in this book is, of course, a necessary one. The peppermints are probably even necessary as caloric supplement. But a settler mindset in the modern era can lead to problematic consumerism.

ANAGNORISIS

We can see from observing this family how we must not hold onto things, not even live things we sort-of love, like oxen. To everything a season and a purpose.

NEW SITUATION

We’ve seen how the settler family spends a year. If they’re lucky and no misfortune comes to them, the following year will continue in the same way, except the children will be another year older — stronger and more highly skilled.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Let’s turn briefly back to McCarthy’s dystopian novel, and what Sean Pryor has to say about that:

The man’s death finishes the novel, but the pronouns’ anonymity means the boy takes up well established rhythms without interruption: “when he woke in the morning”. Soon after, just as his father had, “he walked out to the road and he looked down the road”. Here rhythm signals the cruel indifference of biological succession, made ironic by the threat of humanity’s extinction. … The cosmos is miserably rhythmic.

Sean Pryor

Without stories such as “The Ox-cart Man”, The Road wouldn’t be ironic, because there’d be no straight version of the story to serve as juxtaposition. The Road is the ironic version of “The Ox-cart Man”, if you will. Whereas McCarthy’s story is dystopian, “The Ox-cart” characters will continue as their parents have, continuing to go forth and multiply.

In the picture book, children learn skills from their parents (pedagogy). In The Road, the grown man learns things from the boy (andragogy) e.g. in the opening dream, he wanders into a cave and the child takes him by the hand. There’s no point teaching the boy anything because he won’t make it to adulthood. Hope for the succession of humanity itself is gone.

RESONANCE

See, I can’t really get on board these cosy pilgrim stories anymore, not for more than ten minutes at a time. I’m thinking about all the people these stories don’t serve: The disabled people, who cannot contribute to capitalism, and nor should anyone have to. Where is the space for the disabled in stories such as these? What happens to a family when disability happens or old age sets in? Every scene in this story is an example of give and take, suggesting the universe provides so long as individuals work hard.

But does it? Is that really how it works? No. Income inequality has never been worse. Money itself makes money, not hard work.

Separately, the rhythm of the prose and the seasons of “Ox-cart Man” strongly suggests the way things are in this book is how things should always be.

Where is space for the queer kids who cannot continue in the way of their parents and grandparents, in a world where the family don’t only function as your emotional support but also — mainly — as co-workers? When women hoard all the feminine-coded skills and men hoard all the masculine-coded skills, what happens when that binary is broken?

For an exploration into the realities of queerness in the milieu of stories such as “Ox-Cart Man” see The Power of the Dog, directed by Jane Campion.

Anyway, which of these stories is right about the future of humankind? Will everything end? Yes. Even if we manage to leave Earth and upload our consciousness onto artificial bodies which can travel through vast swathes of time once the Sun burns out, the universe itself will end. That’s not conjectural; scientists know this.

But the rest of us have a helluva hard time accepting it. Thank goodness for stories like “Ox-Cart Man”.

How will the world end? The most likely scenario according to physicists today:

- All the galaxies move away from us. We merge with those nearby.

- 95% of all the stars that have ever been and ever will be have already formed. The universe as we know it is almost over.

- Different stars have different lifetimes. The bigger the star, the shorter the lifetime. Low mass stars can have lifetimes of a trillion years or so, but even those are also going to die.

- At the end it’ll be a couple of dying red stars and a lot of black.

- There will be a few black holes, but those also die. (According to current theory they ‘evaporate’.)

- When there are no stars and no black holes, particles will start to decay. Protons will eventually decay.

- The only thing left in the empty universe will be a trace amount of radiation (the waste heat of all of reality). This is called The Heat Death of the cosmos.

We don’t know if something else will happen once we get to a Heat Death universe. Maybe a new universe pops up out of the extremely cold heat bath of the post Heat Death cosmos. People disagree on the likelihood of this scenario.

Others think the Heat Death may evolve into a new Big Bang. It could be cyclical. But even if the universe does regenerate, it has nothing to do with us.

But the current calculations don’t lead us to anything in particular in that regard. As far as we know, the universe keeps expanding at a steady rate, with nothing of interest in it.