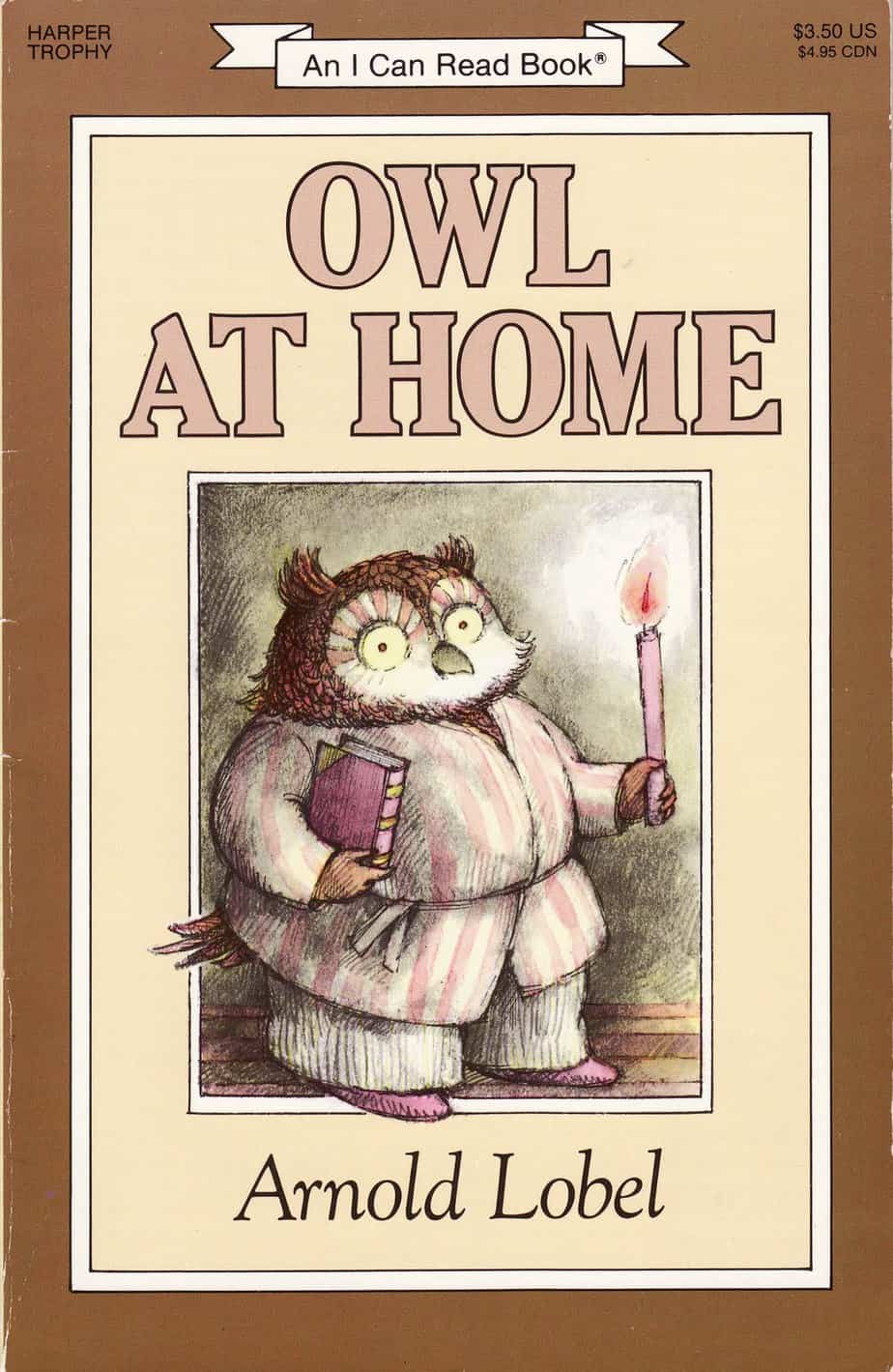

Owl At Home is a 1975 picture book written and illustrated by Arnold Lobel. The book comprises five very short early reader stories about a kind, anxious and lonely owl. These owl stories, along with the frog and toad stories come from the second phase of Lobel’s creative career, in which he tapped into his own emotions and acknowledged he was writing “adult stories, slightly disguised as children’s stories”.

In the classroom, Lobel’s picture book would make a good companion to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “To The Moon“. Owl At Home would also make a good introduction to discussions about the theme of loneliness, present in a great many works.

Owl lives by himself in a regular Western-style dream house (with the upstairs, the hearth, and everything you’d expect to see in a picture book dream house). Although published in the 1970s, there’s nothing 70s about this dream house — there are 1800s/early 1900s details, such as the candle beside the bed. (There doesn’t seem to be electricity.) Picture books set in this era feel atemporal to a modern audience. I’m not sure if this house is in fact inside a tree, because we don’t get an establishing shot.

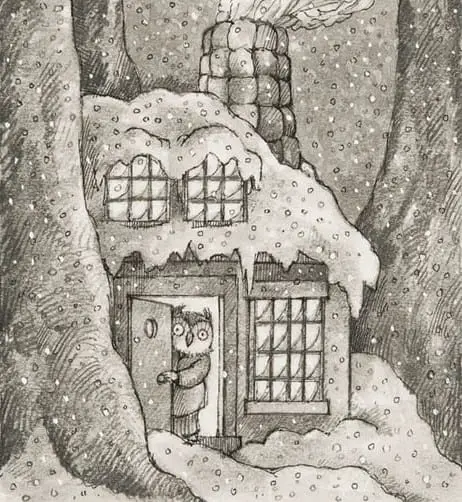

THE GUEST

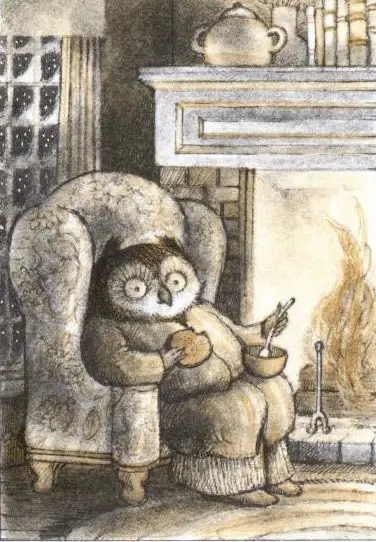

An owl is the perfect animal representation for a stunned and alone person. Lobel’s wonderful owl sits in his arm chair next to the fire and all seems to be well. He’s eating pea soup and hot buttered toast for supper. (The hot buttered toast ends every Mercy Watson story by Kate di Camillo and Chris Van Dusen — the ultimate in cosy fare for the Western reader.)

Except for those massive, stunned eyes. Eyes are super important in character design. The detail around Owl’s eyes draw us to them — those small pupils, that barely visible mouth beneath the beak, encouraging us to take all we need from the eyes.

Something is wrong with this scene, right? Despite the cosy hearth, despite the hygge food, despite the comfortable chair and comfortable bedroom attire.

Owl thinks he hears someone knocking his door.

“Who is out there banging and pounding at my door on a night like this?”

After being pranked two times he concludes it’s the winter, who wants to come in. Considering himself a kind owl, he opens his front door to let the winter in, and his living room fills with snow.

The reader knows that opening your door wide to let in the winter as a kindness is not exactly wise. This owl is an inversion of the Wise Owl archetype, also lampooned by A.A. Milne in his Winnie-the-Pooh stories.

Owl’s house becomes chocka full of snow. I might think this were a typical picture book exaggeration a la The Magic Porridge Pot (in which an entire town becomes overrun with a flood of porridge) but I’ve seen a documentary about people living in Antarctica, and I now know that there are parts of the world in which leaving the door open (or leaving any nooks and crannies open) will result in a building literally full up with snow.

Owl tells the winter to go away. The snow melts away. Owl re-lights his fire, sits back down in his chair and quietly finishes his supper.

Owl’s personification of an unseen phenomenon is very picture book/folkloric. Compare with Hildilid’s Night, in which an old woman living alone (much like Owl) tries to sweep the scary dark out of her house. No surprise, Lobel illustrated Hildilid’s Night four years earlier in 1971. This is basically the emotionally inverted Owl version of that.

STRANGE BUMPS

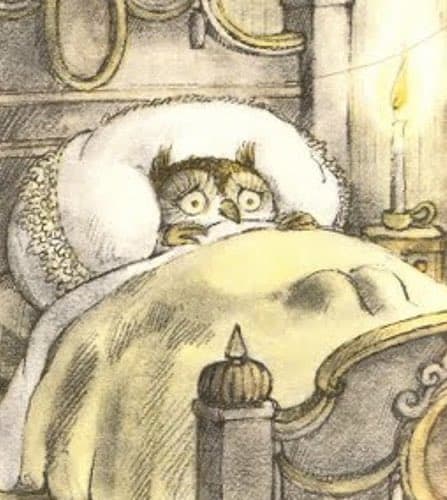

In this story, the reader is in audience superior position. We understand immediately that Owl is scared of his own feet. We are therefore not focusing on the ‘surprise’ of the bumps, but instead focus on Owl’s psychology. We will probably see ourselves in Owl, even if we haven’t been afraid of our own feet, but of other things during Nightmare Theatre.

First there’s the catastrophising: “What if those strange bumps grow bigger and bigger while I’m asleep?”

Owl pulls the covers off his bed but only sees his own two feet. This is the cosy picture book version of cosmic horror — something terrible is happening but looking right at it ain’t gonna help. It’s inexplicable.

Owl is your classic comedic character who tries to overcome a (ridiculous) problem by making a ridiculous plan.

Finally, to conclude the Big Struggle phase, Owl jumps on his bed, angry at the universe. The bed breaks. Owl runs down the stairs and decides to sleep in his chair near the fire. The bumps have won.

Overall, the fact that Owl is afraid of his feet shows that he is afraid of absolutely nothing at all. This is a story which helps us put our own fears into perspective, without minimising them.

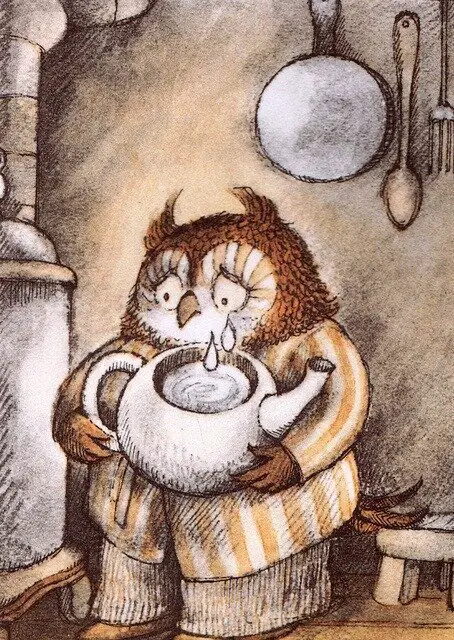

TEAR-WATER TEA

Owl decides to make himself a cup of tear water tea, which is pretty gross. Basically, he makes himself cry until he’s got enough to drink then heats it to tea temperature. First, the tears. So Owl sits down in his chair beside the stove and enjoys a cathartic cry.

Psychologists have studied crying and loneliness and asked: Is it really cathartic to cry? The answer depends: If there’s someone there to help you through your sadness, then crying can be cathartic. Otherwise, not so much.

Owl thinks of many sad things. These are the sorts of sad things that are a little regrettable but not really all that sad. There’s no death, for instance. In lieu of, there’s the hint of death. What all of these sadnesses have in common: They’re evidence of the fact that nothing lasts forever. Some of the sad things emphasise abandonment:

- Chairs with broken legs

- Songs that cannot be sung because the words have been forgotten

- Spoons that have fallen behind the stove and are never seen again

- Books that cannot be read because some of the pages have been torn out

- Clocks that have stopped with no one near to wind them up

- Mornings nobody saw because everyone was sleeping

- Mashed potatoes left on a plate because no one wanted to eat them

- Pencils that are too short to use

I’m reminded of the picture book Some Things Are Scary, which is also a list of things which induce a certain emotion (in that case, fear). Genuinely scary things are interpolated with humorously scary things. It’s a remarkably simple but effective book.

UPSTAIRS AND DOWNSTAIRS

Owl’s picture book dream house has an upstairs and a downstairs. Whenever Owl is downstairs he wonders how his upstairs is. Whenever he’s downstairs he wonders how his upstairs is. So he tries to be both upstairs and downstairs at the same time.

This simple metaphor has a wide variety of applications.

For me, I thought of my life as an emigrant. Emigres are familiar with the sensation of never being in two (or more) beloved places at the same time. Also, we can never have the best of our two home countries in one place. This is a constant regret, something we cannot change, and that we must therefore learn to live with. “I am always missing one place or the other,” says Owl.

Here’s what else it could mean, depending on the reader:

- The bifurcation of the self between home and work (we can never give 100% of our time to both). Owl runs himself ragged trying to be in both places at once.

- The wish to be one way but also another (conflicting) way e.g. a nuclear family man but also a gay man. (Once you know a bit about Lobel’s biography it’s hard not to see his life in his work.)

Young children have not yet developed the capacity (or the opportunity) to experience this bifurcation of self. “Upstairs and Downstairs” is therefore a good example of a ‘children’s book’ which will be read on a literal level by children but on a metaphorical level by adults. The Wind In The Willows is another (though I don’t know many children who truly love that book). Another example is John Brown, Rose and The Midnight Cat.

That said, I think there will be slightly older children who understand, at a visceral level, what Owl is experiencing. Children who divide their time between parents/caregivers will get it. And children who attend school will also get it, since the requirements of school are different from the requirements of home.

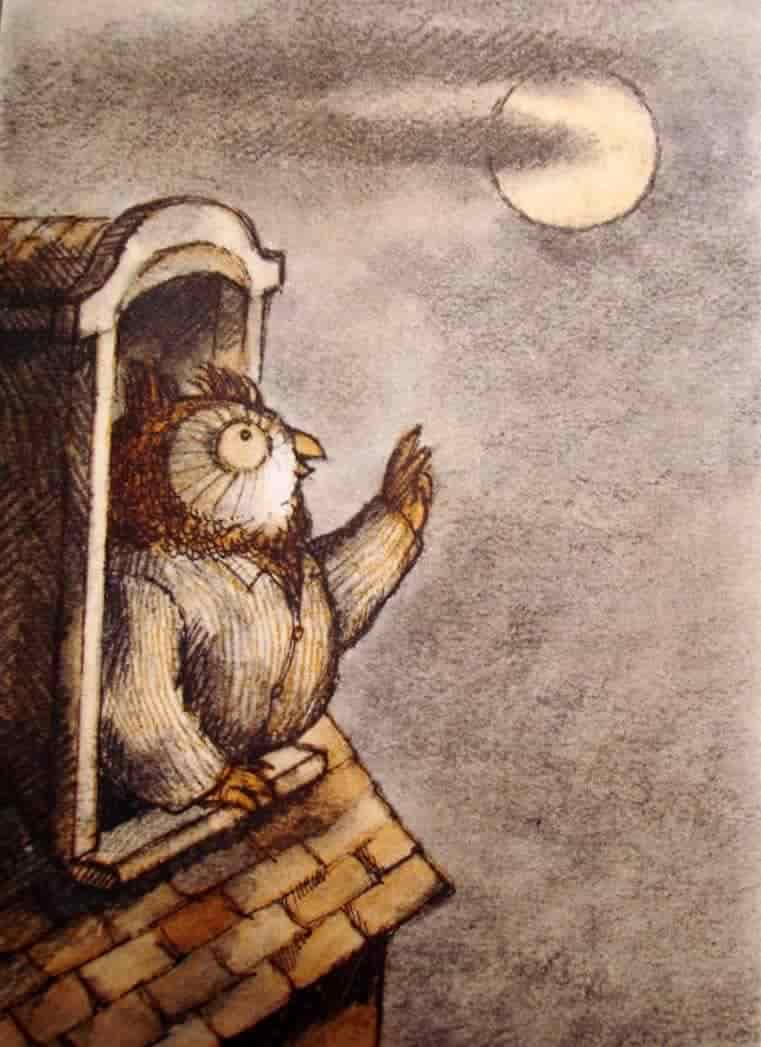

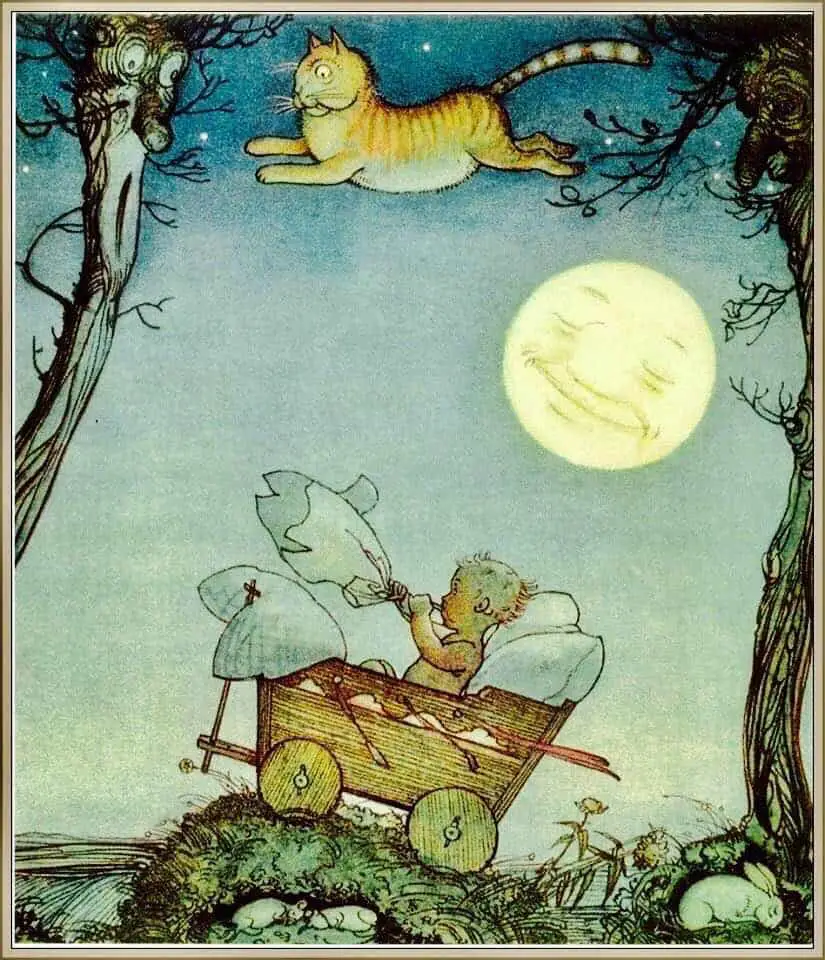

OWL AND THE MOON

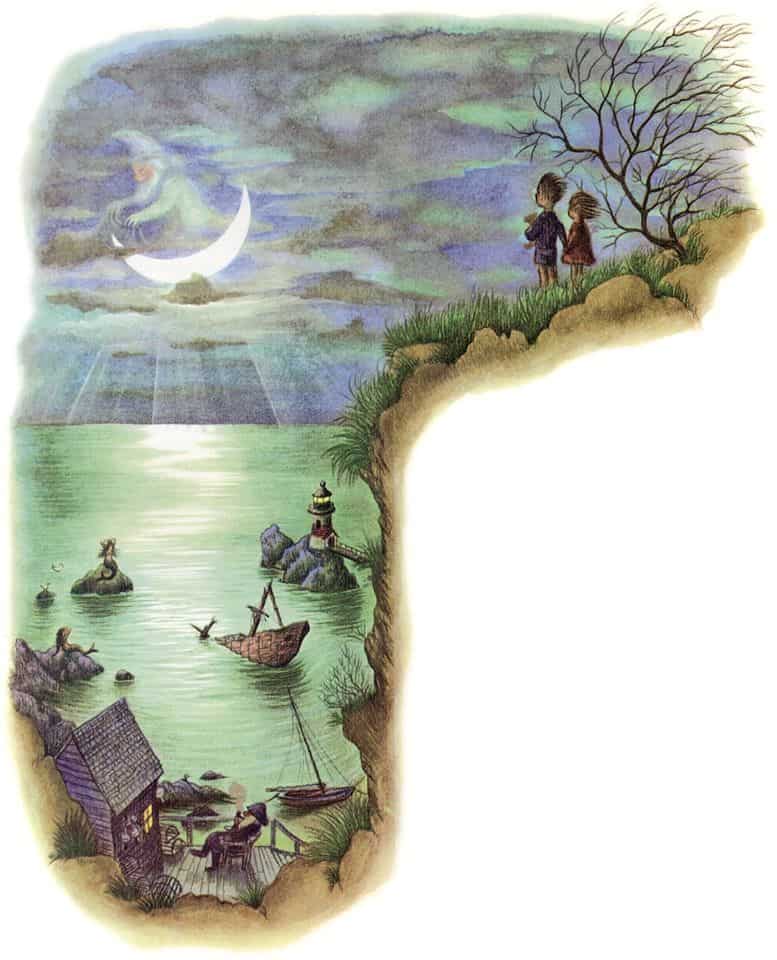

This story takes place outside Owl’s home. He’s sitting on a large rock at the seashore.

Owl believes the moon must be his friend. Humans are adept at personifying the moon. Many illustrations give the moon a face. A crescent moon looks like a profile, or a boat, or some kind of cradle.

Lobel avoids putting a face on his moon, because the reader is not supposed to think that the moon is anything other than the moon. Owl looks up at the moon and because it never seems to get any smaller, he believes the moon is following him home. Now he gets a bit freaked out, though he consoles himself with the thought that the moon is following him home to light his way.

Owl tries to prize himself politely away from the moon who’s following him home, and I think many women can probably relate to this experience, perhaps after a bad date, perhaps at a bar, where certain men have absorbed the dominant cultural message that persistence pays off.

Eventually the moon becomes obfuscated by a cloud and Owl assumes the moon has finally listened to him. He is also sad because it’s never fun to say goodbye to a friend.

But the moon reappears. Owl is no longer so lonely, thinking the moon a ‘good round friend’. Now he is able to sleep. The moon functions as a kind of night light.