If you like playing Red Dead Redemption, if you enjoyed The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, I recommend “The Outcasts of Poker Flat“, a short story by Bret Harte, published in the late 1800s as the century was coming to a close.

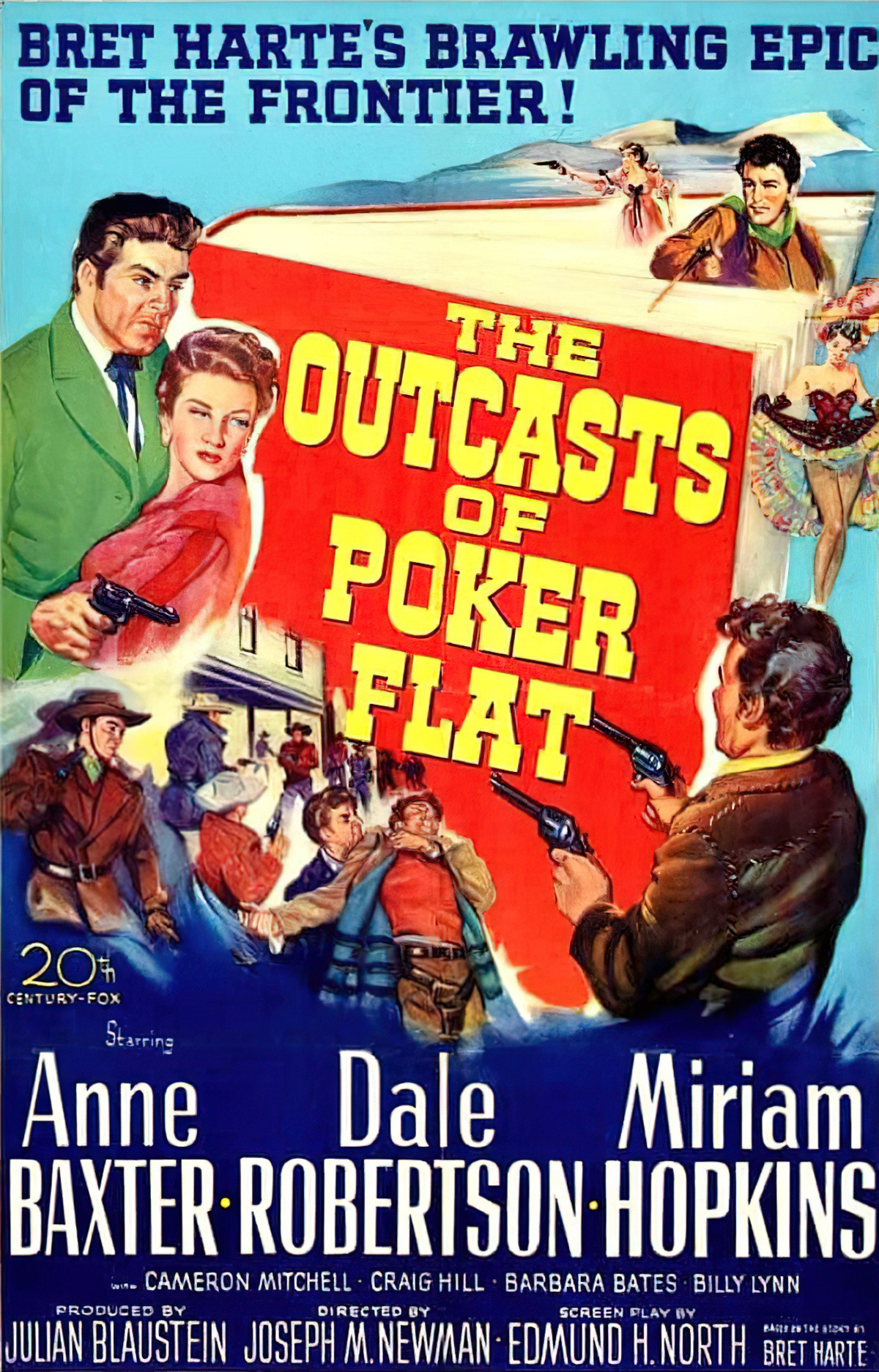

This short story was adapted for film in 1919, 1937 and again in 1952.

But the version with the highest rating on IMDb is the latest one — a TV movie from 1958. Good luck finding it, though.

Then [in 2009-10] the composer Andrew E. Simpson wrote a one-act chamber opera dramatizing the story. It was performed most recently in 2012 (to positive reviews), and from the summary appears to follow the source material much more closely than any of the cinematic adaptations.

Poker and Pop

This story remains interesting to a contemporary audience for its reminder that we thought quite differently about what it takes to live a good life, just 120 years ago. I really enjoyed most of it, though I want to rewrite the ending.

Content note for suicide, with a large dose of sexism near the end.

STORY WORLD OF “THE OUTCASTS OF POKER FLAT”

The setting is a very specific November 22 1850, in a town called Poker Flat, in Northwestern California.

There are two towns that are known as “Poker Flat” in California: one that is located in Calaveras County and one that is located in the Sierra County near in the Sierra Nevada. While there has been minor dispute over which Poker Flat Harte’s story is set in, it likely depicts the latter town in Sierra County because Harte’s characters are forced to traverse part of the Sierra mountain range.

Owl Eyes

Here it is on Google Earth, if you’re viewing this in Chrome. There’s not much there now — but I do spy one ambiguous human structure. I hope there’s at least a plaque which mentions the short story.

I’m thinking of a town a bit like Deadwood (South Dakota) — full of men, drinking and gambling, without the moderating influence of ‘Sabbath’. The illegal town of Deadwood popped up 20 years after this story is set, comprising squatters after gold, and the services around them. While Deadwood has remained in our collective memory as a lawless, wild Western town, there must have been many more like it.

THE SEASONS OF “THE OUTCASTS OF POKER FLAT”

At first it washes over me that the month is November, probably because I live in the Southern Hemisphere, when the end of November is warm, perfect for camping outdoors. Stranded outside in Australia at the end of November? You’d be fine — though covered in mozzie bites, probably. I don’t tend to associate California with snow, partly because I’ve watched Thelma and Louise and Animal Kingdom — no snow.

But I am reminded later in the story that, for Americans, November 22 marks the onset of winter, a month before winter solstice. Of course it snows in the mountainous parts of California, ie. The Sierras, the Cascade mountains.

More on The Seasons of Storytelling.

POKER FLAT

There’s something curious about Harte having chosen to include “poker” in the name of the California town from which a poker player is banished and where the game is associated with other activities (thievery, prostitution) deemed “improper.” It almost seems like the people of Poker Flat are denying something essential about themselves when trying to rid the town of the game — or at least the town’s best player.

Poker and Pop

WHAT WAS GOING ON IN AMERICA IN 1850?

- Never heard of him myself, but Millard Fillmore was sworn in as America’s 13th president. The guy before him died.

- America had 31 states and 4 organised territories at this time. California had been an American state only since September 9 of that year.

- In September the Fugitive Slave Act was passed by congress. This was a terrible law which required that all escaped slaves, upon capture, be returned to their masters and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate.

While this particular story is not about slavery and not about California’s new statehood, all of this provides an important cultural ambience which affords the contemporary reader an insight into how harshly humans could treat other humans back then. (And still do, in certain contexts.) For Bret Harte, writing this story almost 50 years later, America had undergone huge changes, most notably industrialisation, civil war and the abolishment of slavery. To Harte and his contemporary readers, 1850 would have felt like an entire lifetime ago, harking back to an almost mythic past. This marked the beginning of the age of the Western Story, actually. The Western was really popular with a male audience in particular, right up until the 20th century world wars, after which readers no longer really believed in expansionism and violence as an ideal, and since then we’ve only had ‘anti Westerns‘ (which we shorten to ‘Western’, forgetting how ridiculously racist and optimistic those early ones were).

HARTE’S OWN LIFE

As I already mentioned, Harte lived through an era of huge change. The America he was born into was absolutely not the America he saw as an old man.

For a time he worked as a reporter and was left in charge of a newspaper called the Northern Californian for a time. During that time he covered the 1860 massacre of 80-200 Wiyot Indians. He condemned the slayings, citing Christianity. He said no civilised peoples should be doing that to other peoples.

Not everyone agreed with that. After he published his editorial Harte’s life was threatened. He was forced to flee a month later. He quit his job as a reporter and moved to San Francisco.

In short, Harte knew what it was like to be shooed out of town. He’d also seen great brutality at close range. By the time he wrote “The Outcasts of Poker Flat” he had also seen great riches and also poverty as his writing income waned. He may have even contemplated suicide himself. From a letter he wrote to his wife, referring to the winter of 1877-1878:

I don’t know—looking back—what ever kept me from going down, in every way, during that awful December and January.

Harte had also fallen out with Mark Twain, previously a friend. Twain called him ‘a liar, a thief, a swindler, a snob, a sot, a sponge, a coward, a Jeremy Diddler, he is brim full of treachery’. So it’s likely Harte felt some sympathy towards people who are thusly besmirched. Though the character of Mother Shipton is a crass woman, Harte eventually leads his reader to empathise with her and respect her.

By the time Harte wrote this story, he’d moved to England, where he stayed until he died. He left his wife and children in America and regularly sent them money from his writing income, though he maintained he couldn’t afford to travel back to America to see them himself.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE OUTCASTS OF POKER FLAT”

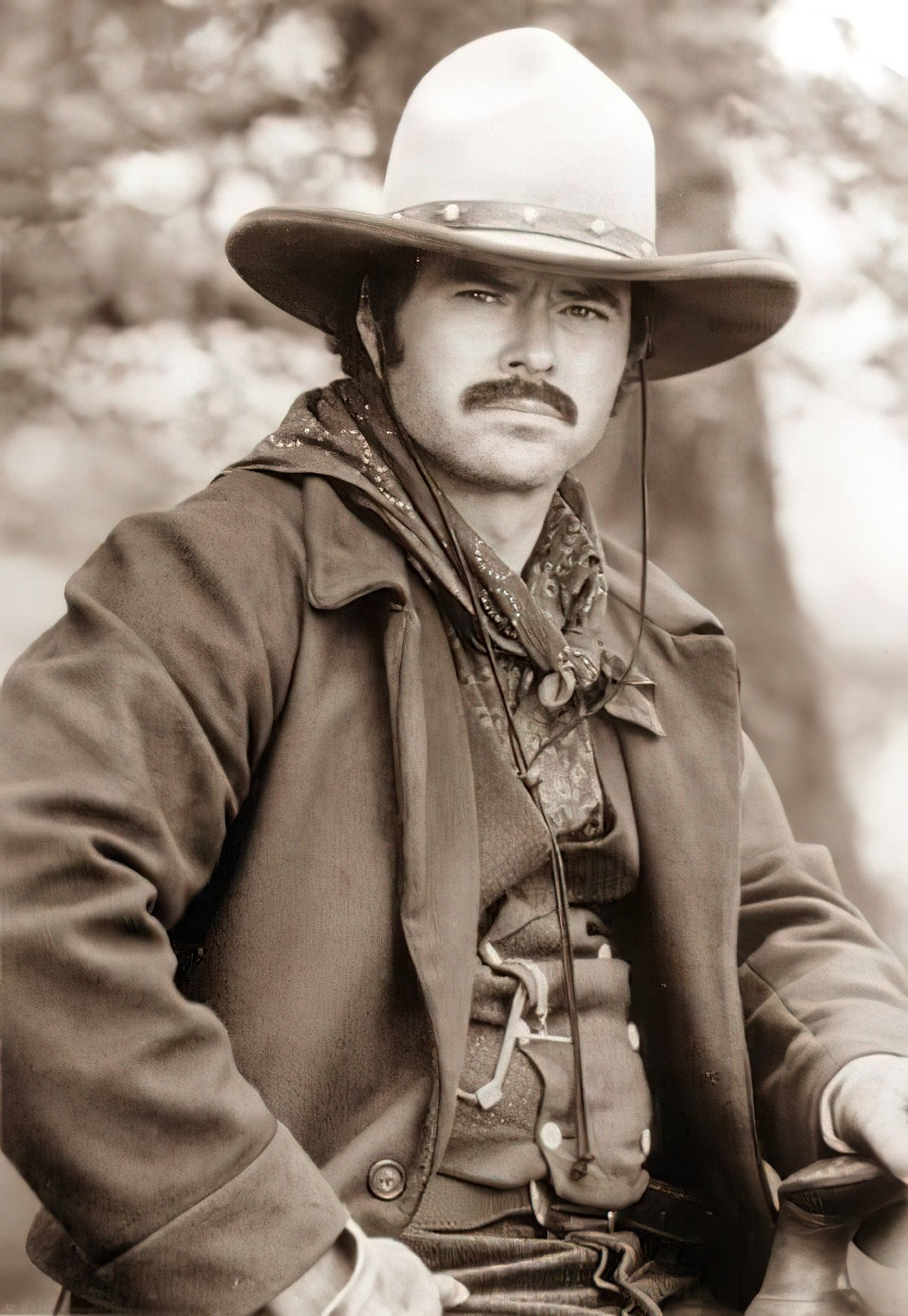

In the story, John Oakhurst, an outsider from a place known as Roaring Camp, has enjoyed gambling success the previous night. Now it’s morning and the locals are regarding him differently. He’s calm, handsome — your archetypal Western hero. He probably keeps himself cleaner and tidier than typical cowboy types of the era. He is introduced to us wiping the red dust off his boots with his handkerchief. I’m thinking of Jake Spoon from Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

The narrator offers the town’s recent backstory. There’s been a crime spree, including loss of life. A secret committee has formed to get rid of anyone suspicious, or ‘improper persons’. We infer that Oakhurst is this morning’s target, since he’s described as a ‘gambler’. If that’s his profession, he’s hardly respectable. There are two men hanging from a sycamore tree. Sex workers have been shooed out.

Somehow Oakhurst knows all this, and supposes that he’s ‘included in this category’. He’s especially targeted because he’s won large sums of money from the executioners, and if they could justify killing him, they’d raid his pockets and get their money back. A man named Jim Wheeler is named as the personification of all those who have lost money. They consider it against (‘agin’) justice to let a man carry away all of their money. Between themselves, they can justify killing him. However, some had also won money from Oakhurst, and Jim Wheeler’s suggestion is overruled.

The narrator skips the part where Oakhurst is apprehended and led to court. Instead we get the outcome — he’s banished from town.

Like a true antihero, Oakhurst receives this verdict with calmness, understanding the nature of fate. In this he reminds me of much more recent wild West heroes (if not ‘Western’ in the traditional sense), such as Cohle from True Detective.

Mr. Oakhurst received his sentence with philosophic calmness, none the less coolly that he was aware of the hesitation of his judges. He was too much of a gambler not to accept Fate. With him life was at best an uncertain game, and he recognized the usual percentage in favour of the dealer.

Damaged heroes who embrace fate and live pessimistically are a favourite in crime stories set in desolate, flat places where ‘nothing can grow, nothing can become’, etc. (These characters are almost always men.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tliWDMrOjoQ

Annie Proulx also likes to write fatalistic characters, eking out their miserable lives in harsh Wyoming environments. See “Stone City“, “Electric Arrows“, “Dump Junk” etc. Proulx’s fatalistic characters also tend to be men. There is something highly gendered about a fatalistic outlook in fiction. Accepting death as a natural outcome of life is a sign of strength and therefore of ideal masculinity, as idealised by the communities themselves.

Do we still idealise a fatalistic outlook, or do we poke fun at it? True Detective does both. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8x73UW8Hjk

Back to Harte’s story. After sentencing, a body of armed men escorts a small group of individuals to the edge of town. Then the four of them are forced to make their own way to the next camp. The ‘criminals’ comprise:

- A young sex worker known as “The Duchess”. She cries ‘hysterically’.

- A woman known as “Mother Shipton” (a moniker also used by Alice Munro in her short story “Silence“). The name comes from English woman Ursula Southeil, born in the late 1400s. She was better known as Mother Shipton, and was thought to have been a soothsayer and prophetess. The moniker is therefore applied to women who are savvy enough to see what’s coming. She uses ‘bad language’.

- “Uncle Billy”, a suspected ‘sluice-robber’. A sluice is a slanted channel used to filter gold out from dirt or sand. In gold digging eras, diggers would claim their own spot. If they found gold they’d leave it in the sluice for short periods on the understanding that they’d found it, so it belonged to them. But a “sluice-robber” didn’t respect this rule, and would steal gold from other people’s sluices when they weren’t looking. This particular sluice-robber is also a ‘confirmed drunkard’. (I’m guessing he tried to rob the sluices while drunk, hence was easily caught. Either that or the townsfolk used this excuse to get rid of him for his heavy drinking.)

Each of the other three escorted out of town are therefore presented as upset and emotional about their expulsion, in contrast to the calm and collected, fatalistic Western antihero of Oakhurst.

Oakhurst does a chivalrous thing and swaps his own excellent riding horse for “The Duchess’s” sorry mule (note that he has done this great favour for the young woman, not for the older one). For some strange reason she’s not all that grateful to him (and as an erstwhile young woman myself, I’d worry he might want to be repaid in kind, later. Don’t forget, they’re liquored up and have no food.

They’re on their way to a place called Sandy Bar. It’s a full day away, of harsh riding up a steep mountain range. (This really does feel like a sequence straight out of Red Dead Redemption.)

But at noon the young sex worker decides she can’t go any further. She’s not stupid — she’s picked a really picturesque place to stop:

The spot was singularly wild and impressive. A wooded amphitheatre, surrounded on three sides by precipitous cliffs of naked granite, sloped gently toward the crest of another precipice that overlooked the valley. It was, undoubtedly, the most suitable spot for a camp, had camping been advisable.

The even more sensible Oakhurst points out that they can’t stop there because they have no provisions. And they’re still half a day away from Sandy Bar. The other outcasts have succumbed variously to the liquor and only Oakhurst remains fully sentient as he does not drink. It ‘interfered with his profession which required coolness’. This tells us that he probably has so much success at gambling not through any special trickery, but only because he’s the most sober person at the table. In this era, resisting drink is its own superpower.

Oakhurst is freshening himself up at a nearby stream or something when an acquaintance of his just happens to ride by at that very moment — a young man, called Tom Simson, who has been on the receiving end of Oakhurst’s fatherly kindness. Simson is known as “The Innocent” of Sandy Bar. He’s on his way to Poker Flat to seek his fortune, against Oakhurst’s earlier advice — Simson is terrible at gambling and shouldn’t try it again. He’s with his fiance, Piney Woods. They’re having to elope since Piney’s father doesn’t approve of the match. Piney is a ‘stout, comely damsel of fifteen’, who shyly comes out from behind a tree.

Oakhurst gives the old drunkard a kick (I guess to stop him telling Simson what they’re all doing there) and then tries to tell Simson he shouldn’t delay. But Simson is very friendly and points out this is bad place to camp. As it happens, Simson has an extra mule of provisions and knows where there’s a ‘crude attempt’ at a log-house near the trail, where Piney can stay with “Mrs Oakhurst”. (He’s assuming the Duchess is Oakhurst’s wife.)

Now the story pans out to offer the reader a wide angle shot of the party, from Uncle Billy’s point of view as he removes himself to the trees in order to stop himself laughing. From here he sees the expanded party has started a fire and that the weather has changed. ‘The air had grown strangely chill and the sky overcast’. This change in weather juxtaposes against the fact that the arrival of Simson and his young fiancée have cheered the others right up.

Notice how Uncle Billy has been separated from the group. Harte did this by a switch in point of view, like the opponent viewing his prey from a distance, through the trees. This is a very cinematic short story.

Harte continues to create a creepy atmosphere for us:

As the shadows crept slowly up the mountain, a slight breeze rocked the tops of the pine-trees, and moaned through their long and gloomy aisles. The ruined cabin, patched and covered with pine-boughs, was set apart for the ladies.

The women sleep in the hut. The men stoke the fire, lie down outside the door and soon fall asleep. Oakhurst is a light sleeper, and wakes up cold. It’s started to snow. He has to wake the other men before they freeze to death, but he finds Uncle Billy has gone. All the mules have gone, too. The tracks are disappearing in the snow. Level-headed Oakhurst knows there’s no point waking the others up at this hour, so he goes back to sleep, endures the rest of the cold night and tells them what happened in the morning.

Fortunately the provisions were in the log cabin with the women, so the thieving old drunkard hasn’t managed to get away with those. They calculate they can last in this camp for 10 days if they’re very careful.

‘For some occult reason’ (which feels a bit like a hack on the part of the writer), Oakhurst can’t bring himself to tell Simson that Uncle Billy deliberately stole the horses. He cracks on it was a drunken accident, wandering off like that, and accidentally setting free the mules. Perhaps, I deduce, if he explains Uncle Billy’s a thief, Simson will work out that the party have all been ousted for various crimes. “It’s no good frightening them now,” he tells the ousted sex workers.

Simson is happy to share his supplies with the rest of the party.

Now Bret Harte decides to remove Oakhurst from the happy party, dancing and singing around a fire, all against the backdrop of a blizzard. Oakhurst has gone off in search of the path, but doesn’t find it. He witnesses this ‘altar’ from a distance. Even if the reader hasn’t noticed that Harte has used this exact trick before, with the drunkard thief, we probably sense that Oakhurst is now set in opposition to the rest of the party. There’s also foreshadowing, with authorial intrusion reminding us that this is a story of mythic proportions:

Whether Mr. Oakhurst had cachéd his cards with the whiskey as something debarred the free access of the community, I cannot say.

The prophetic nature of ‘Mother Shipton’ also provides foreshadowing of doom:

Through the marvellously clear air the smoke of the pastoral village of Poker Flat rose miles away. Mother Shipton saw it, and from a remote pinnacle of her rocky fastness, hurled in that direction a final malediction.

They’re running out of supplies and snow keeps falling. Although Mother Shipton deals with it by yelling expletives into the void, the others amuse themselves with music, then they start to tell stories. Piney proposes this, not realising that Oakhurst and the women are keeping big secrets and probably don’t want to be telling any stories, lest they reveal their true identities.

So The Innocent starts recounting The Iliad in his own words. He read a translation some months ago. This goes on for another week. A mythic amount of snow has fallen around them. They have little food. They’re now having trouble keeping the fire going because they’re running low on firewood.

Mother Shipton decides to die. She’s been starving herself, saving her supplies. She calls Oakhurst to her bedside before she dies and tells him to give her supplies to ‘the child’ (Piney).

Oakhurst suggests he and The Innocent set off out of there, despite the conditions. Oakhurst leaves extra wood for the next few days of fire and the women realise he’s not coming back, despite promising to accompany The Innocent only as far as the canyon.

The women die after the roof of their hut caves in under snow. The narrator tells us that, when dead, it’s impossible to tell the difference between the pure girl and the dirty one. The image of dead women as ‘art’ reminds me of a film I couldn’t stand, but which met with much critical acclaim — Nocturnal Animals — which well and truly glorifies the murder of women. A murdered mother and daughter are posed in an ‘innocent’ but also in a sexualised way. The sexual past of a woman who is a mother juxtaposes against the implied virgin state of the daughter in a a scene very reminiscent of this one, albeit written with the morality of a full century earlier.

Then we have the fact that suicide was considered a grave sin. When it is revealed that Oakhurst has killed himself rather than fulfil his promise of returning to the young women, the narrator tells us that the strongest man has turned out to be the weakest. Even Mother Shipton did something good before she died by sacrificing her food for the virtuous younger woman. But Oakhurst has done nothing (did he keep those rations for himself?) and now he has ‘committed’ suicide, akin to committing murder in those days.

The Judeo-Christian idea that suicide is a sin does not come from the Bible, in fact, but rather from a macho culture in which it is mistakenly seen as ‘the coward’s way out’. By giving us this ending, Harte has built up a man who conforms to every masculine ideal of the time — the ultimate Western hero — then attempts to subvert that message by revealing that actually he is a coward. Harte is very explicit about this in his narration:

…beneath the snow lay he who was at once the strongest and yet the weakest of the outcasts of Poker Flat.

THE MESSAGE THAT SUICIDE IS A FORM OF WEAKNESS

But this message doesn’t work for a contemporary audience, or even for a non Judeo-Christian audience. In Japan, for instance, suicide is traditionally seen as the most noble way out of an impossible circumstance, and supremely courageous.

We now have a much better understanding of the neurobiology of suicide, an understanding which has continued to evolve through the 20th century. We’re still not fully there:

Suicide was traditionally regarded very much as a kind of consequence of social factors. Émile Durkheim in France, in fact many others before him, had noticed the relationship of suicide to social changes involving people having been alienated from society and isolated and so on. But relatively recently it became more apparent that suicide was in fact related to major psychiatric disorders. This was done through psychological autopsies: that is, interviewing the families of people who had been unfortunate enough to die by suicide. It turned out that over 90 per cent of all suicides had a psychiatric disorder.

There was a spate of youth suicide that began in the United States in the 1980s and a little later began to appear in other countries, including Australia, where it became the leading cause of death amongst young people. And, at first, one had the impression that these were well adjusted, popular young individuals who had everything to look forward to in life and their suicide was a complete mystery. One had a sense that this was a shock to everybody. But in fact a careful interview by a professional revealed that in fact over 90 per cent of these young people had a psychiatric illness that antedated the suicide. It was almost certainly the principle cause of their suicide, and most of them are not treated at the time when they’re committing suicide.

Most people who have these mood disorders never attempt suicide, let alone commit suicide. Low serotonin in the wrong place is a factor.

…a compounding factor for struggling teenagers could well be that this prefrontal cortex, so key in impulse control. …we know that mood disorders are transmitted familially and that suicidal behaviour, its predisposition, is transmitted familially.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE OUTCASTS OF POKER FLAT”

SHORTCOMING

This is a classic case of a character whose strength is also his shortcoming:

That said, poker has prepared Oakhurst well for the present trial. Long sessions have meant he’s “often been a week without sleep,” thus preparing him to handle the test of physical endurance the trip has presented. Poker has also helped equip Oakhurst with a kind of mental fortitude to withstand the sudden misfortune that has befallen the travelers.

“Luck… is a mighty queer thing,” he tells Simson. “All you know about it for certain is that it’s bound to change. And it’s finding out when it’s going to change that makes you.”

Though his shortcoming is kept as a reveal, Oakhurst’s shortcoming is that his fatalistic attitude leaves him susceptible to suicide. The reveal forms a bit of a ‘reversal’ when it comes to understanding his psychology — the reason he seemed so calm and collected, even while cast out of town with other ruffians, is because this didn’t stand in the way of his wish to move on anyway, to a completely different town….

DESIRE

… where he would continue to play cards and win a good living.

OPPONENT

So in this story, the townsfolk who throw him out of Poker’s Flat aren’t his opponent.

The drunkard thief is his surprise opponent — surprise because he seems completely ineffectual. But he’s got a wicked plan of his own — he’ll steal the horses and take off in the middle of the night.

PLAN

His plan to keep his true circumstances secret in order to share in Simson’s supplies does work initially, but nature is the bigger opposition, and keeps on falling, snowing them in.

Eventually, when Oakhurst realises they’re all done for, he makes like the drunkard and leaves two vulnerable women alone.

BIG STRUGGLE

Oakhurst’s own death takes place off the page, but Mother Shipton’s death is on the page, and stands in for his own. Her generosity also juxtaposes against his own.

ANAGNORISIS

I believe Oakhurst has a anagnorisis when the author first removes him from the rest of the group. But this is one of those stories in which the Anagnorisis is kept off the page.

NEW SITUATION

Because the Anagnorisis has been kept off the page, we’re given a didactic bit of narration in the final sentence, told that a man who appears strong is actually weak.

The entire party is dead, though they all died with varying degrees of culpability and innocence. The women — one a dirty whore, the other a pure and kind country virgin — are now ‘equal’ (in the eyes of the Lord) because they both tried their hardest to survive. But because Oakhurst ‘gave up’ prematurely, shooting himself with his gun rather than letting hypothermia take him more gradually, in death he has lost any respect.

The author never tells us what happened to The Innocent, which I first think is a narrative mistake. That said, there’s a possible alternative reading: Is this dead body really the body of John Oakhurst, or is it the body of The Innocent, shot by John Oakhurst, who’s made off with the rest of the rations to start a new life, unpursued by the law of Poker’s Flat?

Maybe the final sentence is sufficiently ambiguous to support this reading, as is Simson’s moniker of “The Innocent”.