WHAT IS A STEREOTYPE?

“Stereotype” is originally a printing term referring to the plate used to print identical copies of something, so “break[s] the mold” is an apt phrase for describing something that’s distinctly different from the stereotype. (“Mold” refers to the mold used to create identical objects, not the mold that grows on old food)

The archetypal story unearths a universally human experience, then wraps itself inside a unique, culture-specific expression. A stereotypical story reverses this pattern: It suffers a poverty of both content and form. It confines itself to the narrow, culture-specific experience and dresses in stale, non-specific generalities. […] Stereotypical stories stay at home, archetypal stories travel.

Story, Robert McKee

It’s hard if you confirm a stereotype and it’s hard if you violate a stereotype and it’s hard if you think you’re violating the stereotype only because you hate it so much.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

If you’re the average type of something, you’re “typical”, and if you aren’t the usual type of it, you’re “atypical.” If you fit a stereotype, you’re “stereotypical”. But what is the word for something that’s distinctly different from the stereotypical specimen? What is the antonym of “stereotypical”?

homunculus-argument

(I like ‘anti-stereotypical’.)

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, comedian Dave Rubin (“The Rubin Report”) chats with Cara about gay stereotypes, comedy before YouTube, and his love of the Golden Girls.

READING IS A KIND OF GOSSIP

In reading for character, readers conventionally use their knowledge of the way people in the world around them usually behave to assign traits to characters, to guess about their motivations, to reconstruct their past, or even to predict what they might do after the end of the story.

Reading in this way implies that fiction is a kind of gossip. It assumes that authors say a little bit about the characters they describe so that readers can have the fun of guessing about all the aspects of character and experience they are not told about. […] But, like gossip, guessing about literary characters can misrepresent them by fitting them into categories readers already possess. Readers who want the pleasure of perceiving something more than or something different from what they already know or believe about human nature have to work with a different assumption: that authors carefully select what they choose to say, and that their choices—both what they say and what they don’t say—define what they wish readers to understand.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Perry Nodelman and Mavis Reimer

COMEDY TRICK MAKING USE OF STEREOTYPES

Like many comic writers, Jeff Kinney, author of the Wimpy Kid books, makes use of our stereotypes by giving us just a few details then leaving us to fill in the rest. There’s no getting around it — a lot of comic writers rely on stereotypical views of their audience.

Greg’s older brother Rodrick is set up as a fool. Like lots of stereotypes we hold about dimwits, he can’t spell and is a member of a rock band. Of course, being unable to spell and having an interest in rock music has zero correlation to overall intelligence. But we find this combination of traits funny because it reinforces everything we believe (sort of) about someone who can’t spell ‘loaded diaper’, or who thinks they’re going to become famous via their garage band. Every now and then, however, Rodrick does something amazing. His strokes of genius defy our expectations (based on stereotype) and are ironically funny for that reason.

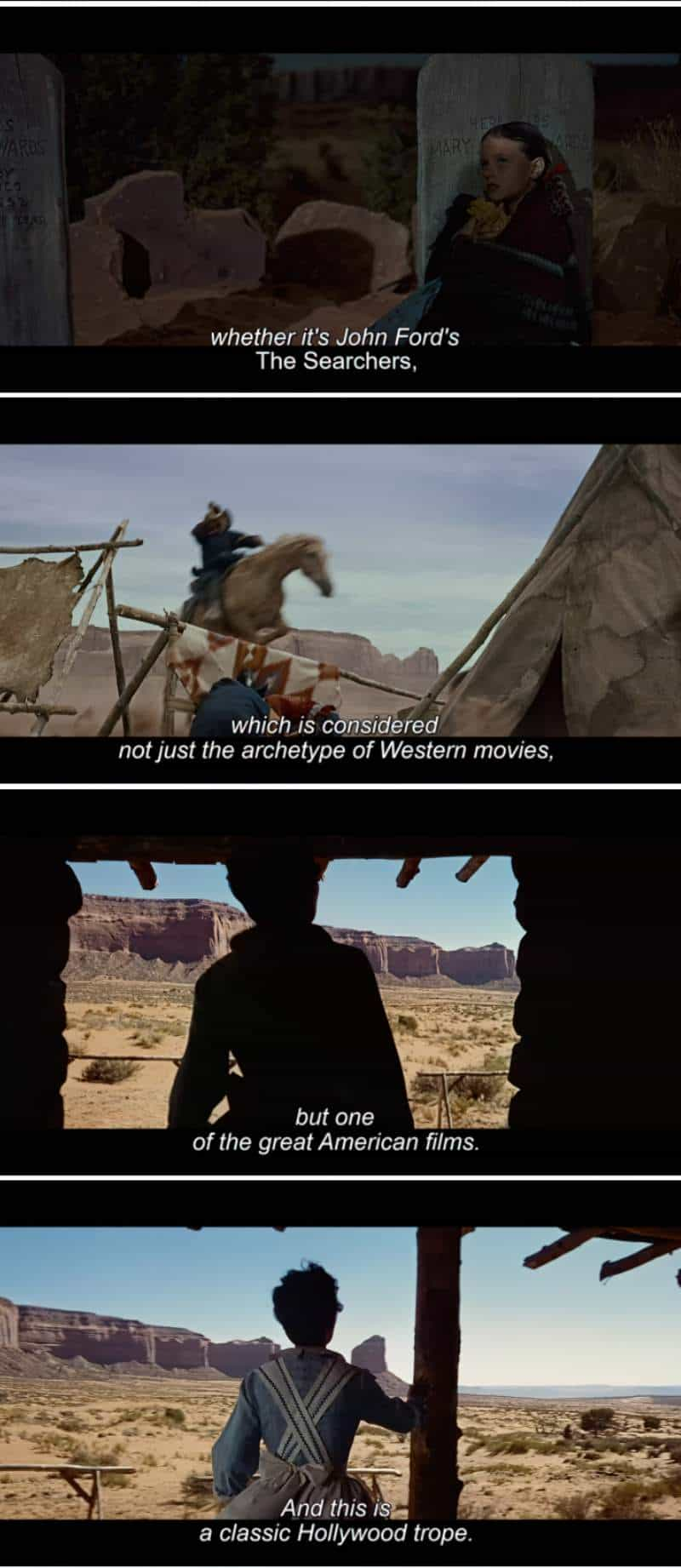

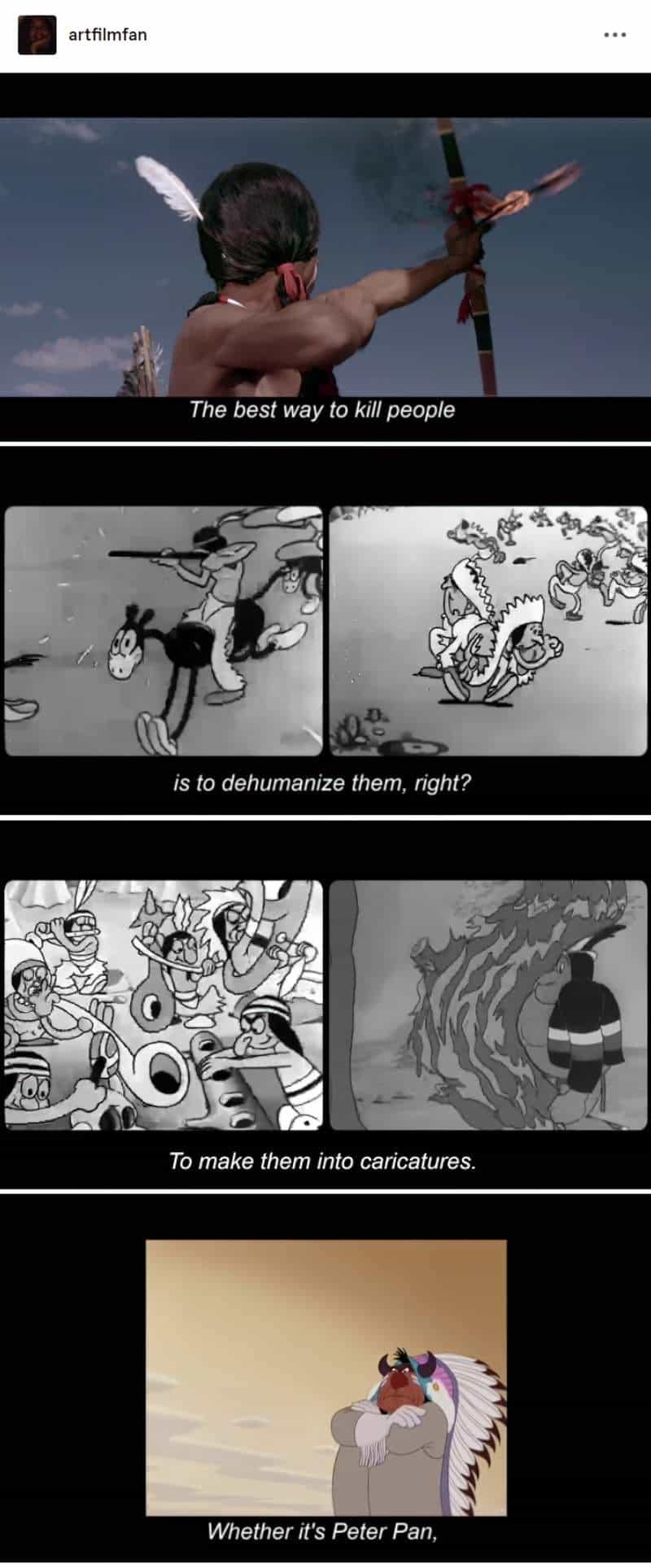

WHAT IS A TROPE?

Saying a story has tropes is kind of like saying a meal has ingredients. Like, hand-wringing about a story having “tropes” is like ordering a chicken salad and complaining that it has chicken in it.

@Coelasquid 6:12 AM · Jul 9, 2021

A trope is a pattern which can be seen time and again in various stories. The site TV Tropes is a good place to start for many, many examples of tropes (not just seen on TV). However, the ‘tropes’ on that site get a little too specific. Some of the most specific examples can’t really be considered tropes at all, except to the most discriminating of story consumers. In order to work, the trope has to be recognised by the audience.

A Revolution in Tropes: Alloiostrophic Rhetoric

Aristotle, the co-called father of rhetoric, supposedly conceptualized his theory of persuasion as a means of bringing meaning to rest. But what if there’s another story, one in which forgotten tropes such as alloiosis turn rhetoric toward the flux and difference?

On this episode of the New Books Network, Dr. Lee Pierce (s/t) Drs. Jane Sutton and Mari Lee Mifsud about how our classical conceptions of stylistic language may be more open opening to otherness than stabilizing meaning.

A Revolution in Tropes is a groundbreaking study of rhetoric and tropes. Theorizing new ways of seeing rhetoric and its relationship with democratic deliberation, Jane Sutton and Mari Lee Mifsud explore and display alloiōsis as a trope of difference, exception, and radical otherness. Their argument centers on Aristotle’s theory of rhetoric through particular tropes of similarity that sustained a vision of civic discourse but at the same time underutilized tropes of difference. When this vision is revolutionized, democratic deliberation can perform and advance its ends of equality, justice, and freedom. Marie-Odile N. Hobeika and Michele Kennerly join Sutton and Mifsud in pushing the limits of rhetoric by engaging rhetoric alloiostrophically. Their collective efforts work to display the possibilities of what rhetoric can be. A Revolution in Tropes will appeal to scholars of rhetoric, philosophy, and communication

New Books Network

WHAT IS A CARICATURE?

This word is very commonly mispronounced. Take a close look at the syllables and chunk it out. The word “character” is not in there. CAR-I-CA-TURE.

WHAT IS AN ARCHETYPE?

Archetypes are fundamental psychological patterns within a person. They are roles a person may play in society, essential ways of interacting with others.

e.g.

- King/Father

- Queen/Mother

- Warrior

- Magician/Shaman

- Trickster

- Artist/Clown

- Lover

- Rebel

Archetype is a five-dollar word for ‘pattern’, or for the mythic original on which a pattern is based. It’s like this: somewhere back in myth, something — a story, let’s call it — comes into being. It works so well, for one reason or another, that it catches on, hangs around, and keeps popping up in subsequent stories. That component could be anything: a quest, a form of sacrifice, flight, a plunge into water, whatever resonates and catches our imaginations, setting off vibrations deep in our collective consciousness, calling to us, alarming us, inspiring us to dream or nightmare, making us want to hear it again and again. You’d think that these components, these archetypes, would wear out with use the way cliche wears out, but they actually work the other way: they take on power with repetition, finding strength in numbers. … When we hear or see or read one of these instances of archetype, we feel a little frisson of recognition and utter a little satisfied ‘aha!’. And we get that chance with fair frequency, because writers keep employing them.

Thomas C. Foster, How To Read Literature Like A Professor

Because they are basic to all human beings, archetypes cross cultural boundaries and have universal appeal.

The idea of an archetype comes from Jung’s psychoanalytical writings. Jung wrote about our heads, but the Canadian critic Northrop Frye took these ideas and applied them to books. Some academics use the word archetype and then make sure to distance themselves from the specifically Jungian definition. This is from a footnote I happened across:

The concept of “archetype” is used here to denote a widely-known story characterised by a repetition in its characteristics (the setting and resolution are predetermined) and a slight variation in its details; the concept of the “archetype” as used in this paper is devoid of the Jungian overtones commonly associated with the concept.

See: Fairytale Archetypes

ALISON HALDERMAN: Don’t people tend to choose an archetype they like and then seek out books that use that theme?

URSULA LE GUIN: Sure. Because people always need new symbols and metaphors.

The Last Interview

PH.S.: If characters are not completely developed in a short story, would you agree that they may be more like types than actually live characters. The French academic Alain Theil, whom you remember, said that he had found only ten types of female characters, such as the light woman, the unsatisfied woman, the deserted woman often divorced and so on… Would you agree with a definition like that or would you think it is unfair?

V.S.P.: It’s a generalisation which may have a certain amount of truth but most of the novelists’ or the short story writers’ duty is to destroy generalization. Supposing I am faced with writing about one of his types, I should have to see that she is not a type. I should have to contradict the view. He might still say you’re writing about a “light woman“ but “you have never seen a light woman like this before“ would be my answer. All human beings are different and I want to see the distinctions. There is something that takes them outside the generality.

interview with V.S. Pritchett

RELATED LINKS ABOUT STEREOTYPES

- World map of useless stereotypes.

- Automotive stereotypes look a bit different in Australia, so this American summary was interesting.

The nature of prejudice is to seek out the extreme and the hypothetical and use it to tar an entire minority in order to lay the foundations for discrimination.

Owen Jones