Northrop Frye was a Canadian literary theorist who died in 1991 aged 78. Frye was considered one of the most influential literary theorists of the 20th century. Sometimes his theories applied equally to children’s literature; at other times he was off the mark. One of his theories — The Displacement Of Myth — does not apply well to children’s literature.

Northrop Frye’s Five Stages Of The Displacement Of Myth

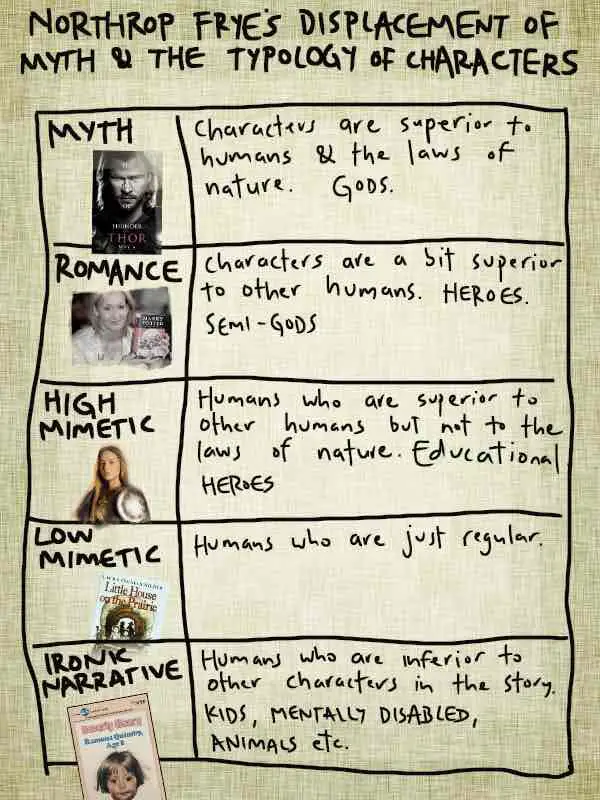

Frye treated literature as ‘displacement of myth’. Here are Frye’s stages, in consecutive order, between full-on myth to what we get today:

- Characters are gods (superior to both humans and to the laws of nature)

- Romantic Narrative (idealized humans who are superior to other humans but not to the laws of nature)

- High Mimetic Narrative (humans who are superior to other humans)

- Low Mimetic Narrative (humans are neither superior nor inferior to other humans)

- Ironic Narrative (characters are inferior to other characters)

(Terminology note: The ‘mimetic modes’ are also known as ‘realism‘. Mimesis basically means ‘copying reality’.)

Examples Of Modern Popular Characters From Each Of Frye’s Five Stages

- Superheroes in general, though writers sometimes limit their powers in aid of a more interesting story. Superman is one of the few who actually fits this category because Superman was never meant to be relatable. (Before he was known as Man of Steel he was known as Man of Tomorrow, in a much more optimistic age when it was thought that humankind is making its way closer to the ideal mindset of altruism for altruism’s sake.

- The male love interests in Harlequin romances, in which the story ends before more human aspects of his character are revealed.

- Walter White and other genius characters who live among us e.g. Marty Byrde of Ozark which seems to be modelled upon Breaking Bad.

- Don Draper; the alter egos of secret-identity superheroes. (See: A Psychoanalysis of Clark Kent.)

- Mr Bean,

If you try this exercise yourself, you’ll probably find that contemporary stories tend to fall into the bottom two categories. It’s much harder to find genuine examples from the top two tiers in particular. Some have argued a case for more heroics in stories for adults.

The conventions of literary fiction are that the bourgeois hero (more likely the heroine) be vulnerable, prone to shame and guilt, unable to fit the pieces of the larger puzzle together, and on the same banal moral plane as the “average reader”: sympathetic, in other words, someone we can “identify” with, who reflects our own incomprehension of the world, our helplessness and inability to effect change.

an example of why we need to read about amazing characters, in an opinion from Anis Shivani

The Displacement of Myth and Children’s Literature

How does Northrop Frye’s Five Stages map onto children’s literature? According to Frye, children (and animals) fall into the fifth category — children are regarded as inferior. Since almost all children’s literature stars children, this suggests all children’s literature is ironic.

This is not the case.

In fact, the corpus of children’s literature includes characters from each of Frye’s levels. This has been pointed out by specialist of children’s literature, Maria Nikolajeva, in Aesthetic Approaches to Children’s Literature: An Introduction.

Examples Of Children’s Characters From Each Of Frye’s Five Stages

- The superhero side of Miles Morales; Christopher Robin who to the toys seems like a God. (This also applies to Andy of Toy Story.)

- Edward Cullen and other paranormal love interests in young adult romance; Harry Potter winds up here.

- Rory Gilmore types, who is herself the granddaughter of Anne of Green Gables (very smart). That said, Rory Gilmore had been cut down a peg or two in the Gilmore girls revival, and Anne With An E showed a more vulnerable side to Anne Shirley. Perhaps this means a contemporary audience likes to see more ordinary characters?

- Laura Ingalls, Tom Sawyer, Ramona Quimby, Henry Huggins and all of these kids’ descendants populating realistic fiction, but who sometimes enter a fantasy world. (That said, entering a fantasy world often in itself denotes ‘chosen ones’.) In YA we have Francesca Spinelli (Saving Francesca), the ensemble stars of Tomorrow When The War Began and other ordinary teens who learn to become self reliant after some kind of adversity.

- Greg Heffley, Timmy Failure, Nikki Maxwell and many other stars of middle grade, humorous, illustrated novels starring characters who are mean, dim-witted, accident-prone, or who otherwise feel put-upon due to being the middle child, wearing braces or whatever. We see these characters in cartoons, too e.g. We Bare Bears. Comedy is full of them because these characters are easy to poke fun at. We also have serious YA characters such as Charlie from The Perks of Being a Wallflower, or James Sveck of Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You, who are basically overwhelmed by all the changes happening in their teenage years.

As shown above, children’s literature is as diverse as adult literature when it comes to this particular theory of character. ‘Children’ cannot be lumped into the bottom category. The opinion from Anis Shivani above may in fact mean it’s easier to find heroic characters in children’s stories than in stories for adults.

As a side note, animals can’t be lumped into the ironic category, either. That’s because animals in literature are very often stand-ins for humans.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

The conventions of literary fiction are that the bourgeois hero (more likely the heroine) be vulnerable, prone to shame and guilt, unable to fit the pieces of the larger puzzle together, and on the same banal moral plane as the “average reader”: sympathetic, in other words, someone we can “identify” with, who reflects our own incomprehension of the world, our helplessness and inability to effect change.

an example of why we need to read about amazing characters, in an opinion from Anis Shivani

Roman Mars of the 99% Invisible Podcast has an interesting discussion with the author of a biography of Superman. It’s episode 82. Like me, Roman Mars finds Spiderman a far more interesting character, but as is pointed out, Superman was never meant to be relatable. Before he was known as ‘Man Of Steel’ he was known as ‘Man of Tomorrow’, in a much more optimistic age when it was thought that humankind is making its way closer to the ideal mindset of altruism for altruism’s sake.

This raises an interesting question: Where are we headed? Are humans becoming more kind or more harsh toward others? Steven Pinker thinks we’re getting less violent, for one thing. This is the main argument in his book: The Better Angels Of Our Nature.

A Psychoanalysis Of Clark Kent (from Emory University on YouTube)

Header illustration: ‘Superman’ (WB 1978) theatrical poster illustration by Bob Peak