This week our local agricultural group sent an email containing the following information: Warning: Fox Attacks on Chickens.

In the last few days, 9 chickens have been killed by foxes in Centre St and Daffodil St at 3 properties between 3am and 4am. The fox is able to climb fences 6m in height. Sid Drumstick lost his entire flock in one night. Chicken owners need to keep chickens fully secure overnight. (Names have been changed to protect the victims.)

We have six chickens at our house, and have lost at least that number over the past year. Keeping them secure is quite a job — the coop needs to be locked as soon as dusk falls, which in these winter months is quite early. But then, there’s the bonus of genuinely free range eggs. And chickens are good to keep with young kids. They encourage responsibility, and establish a connection between animals and food products, which is easy to overlook unless children grow up on farms.

Perhaps because of her interest in chickens, our six-year-old daughter brought home a book from the school library called ‘Henny Penny’. Although the school library recently purchased new books for its library, this one is an old one, published in 1968. There is much humorous repetition, great for kids (though slightly tiresome to read!), and it’s a Chicken Little type of story in which an acorn falls on a chicken’s head, and she walks around the farm gathering up other kinds of fowl on her travels, on her way to tell the ‘king’. (The six-year-old wasn’t sure who the king was, thinking it may be the farmer, but this was never resolved.)

Eventually the flock of fowl meet up with a fox, who offers the birds a short cut. Because of many other fairytales about cunning, wily foxes, suspense is set up. Sure enough, the fox leads the birds straight to his cave.

You may know this story as Chicken Licken or Chicken Little, which is based on an international folktale. But I’d somehow missed out on this tale, or had forgotten all about it, so when the birds were lured to the den I was all set for some great escape, in which the birds somehow outwit the fox. I expected this even though I’m a keeper of chickens myself, and know full well that foxes would never in anyone’s wildest dreams be outwitted by a hapless chicken — especially not one who was silly enough to be lead back to his lair.

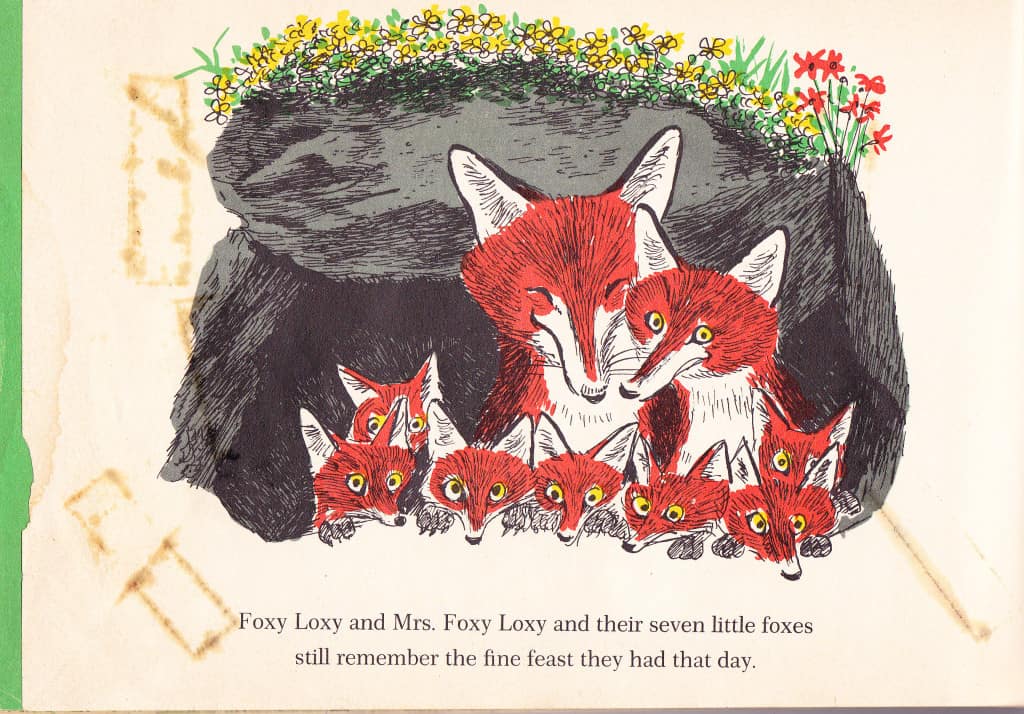

“In they all went after Foxy Loxy,” the story reads, with an illustration of some hesitant chickens and a sly fox with its tongue hanging out.

Overleaf: “From this day too this Turkey Lurkey, Goosey Loosely, Ducky Lucky, Cocky Locky, and Henny Penny have never been seen again. And the king has never been told the sky is falling.” Ah, what bliss! This is an Attenborough style of story, in which carnivorous animals actually eat the meat! Finally:

I was interested to read some of the Amazon reviews:

Unfortunately, the book has not aged as well as it might have. Illustrator Paul Galdone’s story is a bit dull for a while, and then it suddenly becomes a little shocking at the end.- I would NOT recommend this book! Children don’t need an ending where the animals are tricked and get eaten by the fox! I wish I could return it and get my money back!- It’s a classic! Very good lesson learned.

Henny Penny by Paul Galdone is not your modern PC story

The following was from a teacher, who understands the point of the disappointing ending:

Of course, children love to feel smart and they feel much smarter than Henny Penny, who thinks the sky is falling down! Someone else sees relevance to today’s media-rich world: – I have always liked Henny Penny as a good example of the foolishness of assuming that news broadcasts are accurate, which is an especially good lesson in today’s world.

The same reviewer makes a further comment on the ending, which I’m not sure is a recommendation or a resignation. Either way, it’s a comment on how picturebooks seem to have changed over the past generation or so:

Henny Penny and her friends are eaten by Foxy Loxy and his family. In today’s world of fluffed up fairy tales, Henny Penny should probably be rewritten to have received some other consequence other than being barbequed.

Have picturebook endings really become more sanitised, or are we just imagining it?

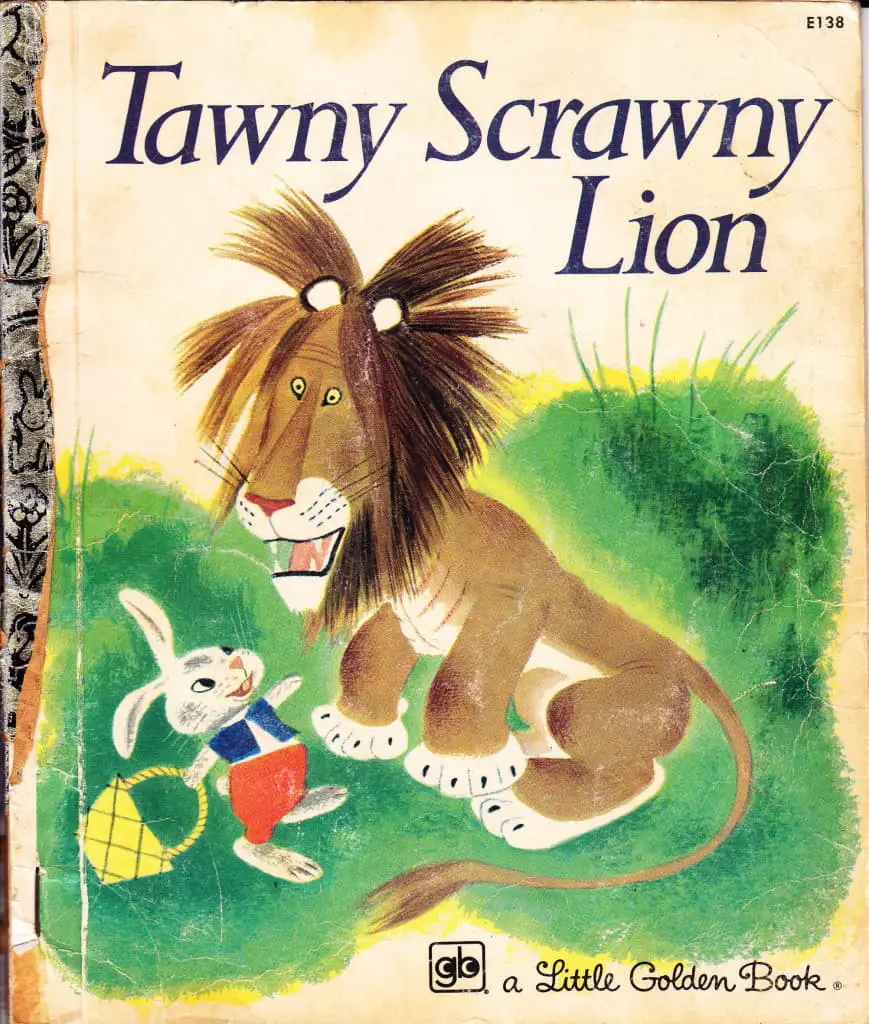

Also this week, my daughter asked me to read a Little Golden Book called The Tawny Scrawny Lion. From what I can gather, this was one of the most popular Little Golden Books (and is ranked number 25 on a Goodreads List). In fact, it’s one of my friends’ favourites from childhood. She told me to re-read it, saying it explained everything about her. My friend is vegetarian, and although this story is not the only reason why my friend is vegetarian, this dietary outcome does speak to the power of children’s literature. This is my own tawny scrawny copy from childhood:

Although I remember the book itself, I didn’t remember the story. After reading it as an adult, I realise the plot makes no scientific sense whatsoever.

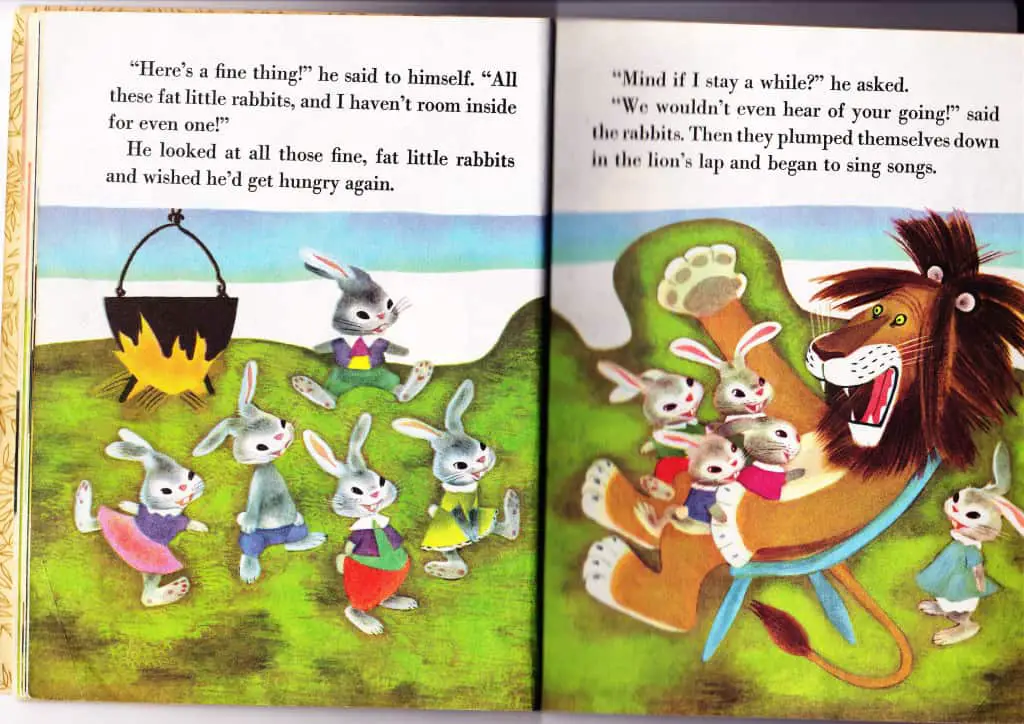

The Tawny Scrawny lion catches everything he chases, but can’t seem to put on weight. Apparently this is down to too much running. Do lions suffer from hypothyroidism or anything like that? I don’t know, but it makes no sense that evolution would favour such a creature. In nature, lions balance their energy expenditure nicely — that’s why they are as efficient as they are today. No matter. I only thought of this as an adult reader. I certainly gave it no consideration as a child.

As you may remember, the lion meets some cute bunnies and the rabbits make the lion carrot stew. When the lion had gobbled all the stew, the rabbits heaped his bowl with berries. And so it continues, until the tawny scrawny lion realises that in fact he thrives on a pescatarian diet. As a consequence, he makes some wonderful new friends:

Not only that, but by eating carrots, berries, mushrooms and herbs (and also some fish, caught by the rabbit) the lion manages to look ‘fat as butter, sleek as satin and jolly as all get out’.

Which makes this true family entertainment. Could a lion thrive on a high-vegetable diet supplemented by fish? Certainly not on fish caught by rabbits, which is why this story is a story, not a wildlife documentary.

Back to my original point about sanitised endings: I now point out that this story was first published in 1952. By 1978 it was onto its tenth printing, according to this battered copy in front of me. In other words, this non-naturalistic ending belongs to the era of today’s grandparents, and actually predates Henny Penny by 18 years.

In fact, Henny Penny may well have been a satire of books such as the Tawny Scrawny Lion. If picturebooks have indeed become more sanitised, this is not a new phenomenon. When we speak of ‘PC modern stories’ we are surely talking about stories from the mid 20th century.

The Contrast of Fairy and Folktales

Perhaps what we really mean when we say that picturebooks have become more gentle is in comparison to the most classic of fairytales such as those collected by Grimm and authored by Hans Christian Andersen. Seek out any of the original translations (or the originals if you are multilingual) and you’ll see the Disneyfication of storytelling, and particularly the endings. The Little Mermaid is a good example of an ending which has been changed to suit a modern audience.

However, fairytales were never meant for children. Fairytales had a dual (multi) audience, and existed as cautionary tales for adults and adolescents. Since the concept of childhood is a fairly modern one, it’s likely children were also told these tales, but they were not specifically designed for kids.

In that case, have picturebooks really become more sanitised? I would argue that no, they haven’t. Picturebooks are not an old artform, and have always been thus. And with every happy ending, you will always find a dark story as counterbalance: a Charlotte’s Web to Miss Spider’s Tea Party; a faithful rendition of Henny Penny for every Disney version of Chicken Little, in which “aliens return everything to normal (except Foxy Loxy, whose brain got scrambled, turning her into a Southern belle, and as a result, Runt falls for her), and everyone is grateful for Chicken Little’s efforts to save the town.”