LITTLEWOOD’S LAW

Around once per month, each of us experiences a “miracle” (an event with odds of one in a million). Across the world miracles are literally happening all the time, but because there are so many of them we perceive them as mundane.

@G_S_Bhogal

No luck was dumb because luck was just another name for miracle.

Margaret Atwood

DEFINITION OF A MIRACLE

Miracle: Divine communication with humans via extraordinary actions. Gods can interact with the human world whenever they wish, but miracles generally need to be asked for by humans.

A miracle story may be considered a subgenre of the disaster story.

Miracles happen only to the fortunate few.

Suspense: No one knows whether God is going to perform a miracle or not. Even Jesus Christ picked and chose who he cured and helped. Humans are told that God has his reasons and those reasons are not for us to know.

THE PURPOSE OF MIRACLE STORIES

My guess was that miracle stories are used to communicate the comforting idea of a benevolent interventionist god. But I’m wrong: that’s not what miracle stories were for. Characters did not witness (what they thought were) miracles and subsequently consider that evidence of God. In the golden age of Miracle Stories, belief in God was a given. Miracles neither proved nor disproved God’s existence.

The actual purpose of miracle stories:

In earlier times, miracle stories which people bothered to write down served a second specific function: To persuade living communities that certain dead holy people should be canonised.

Miracle stories were also to help process trauma. A miracle story creates a memory which allows someone to cope with the shock of disaster narrowly averted. These events will be remembered forever, as near-death experiences generally are.

NECESSARY INGREDIENTS OF A MIRACLE STORY

According to Niels Chsristian Hvidt:

- Divine Intervention: God acts beyond or in ways different from the natural order.

- Psychology: Characters who witness the event will interpret it as a miracle.

- Symbolic Interpretation: The miracle is regarded evidence of God’s wish to communicate with humans.

NARRATION

The character narrating the story already knows the entire story as they embark upon the retelling of it. This affects how the entire story is told.

STRUCTURE OF A MIRACLE STORY

SETTING

The senses of hearing/sight/touch are emphasised. Miracle stories tend to feature dead people and hearing, sight and touch are the senses most involved in that. (Assuming they are discovered soon after death, in which case smell may come into it.)

How the ‘magic’ works: Bodies cannot come back to life via miracle more than a few days after the death.

THE BEGINNING

A miracle story opens with a description of why a miracle was prayed for in the first place. Many miracle stories feature dying children. These stories are broken into two basic categories:

A child becomes ill, gets sicker and dies

This plot will detail how close the parents are to the child, how much the child is loved etc.

A child dies suddenly in extreme circumstances

The parents discover their child is dead, or are told by someone else who was present at the time of the accident. Commonly, characters try ‘rolling’ the child to see if the child can be brought back to life.

The dead body would commonly be left for a few hours to see if it comes back to life.

EMOTIONAL RESPONSE

Next comes a description of the emotional response of the left-behind. In contrast to films today, in which any screaming sound effects issue forth from a woman, in Swedish Miracle Stories, it is the men who are more outward in their response to grief. (This is regionally dependent.) Some have suggested this is because men’s activities were more societally focused and therefore public. In contrast, women were more confined to the home. Women were family-focused and therefore quieter. In many miracle stories both men and women cry equally. Crying is heavily culturally scripted.

Another reason why Swedish men cry in miracle stories: The strong emotion of a bereft father demonstrates the equally strong tie between father and child.

In England and on the rest of the European continent, men crying is seen as shameful.

Expressions of grief are greater when the death is sudden and unexpected.

Today we talk about Stages of Grief. Miracle stories emphasise the stages of disbelief and confusion.

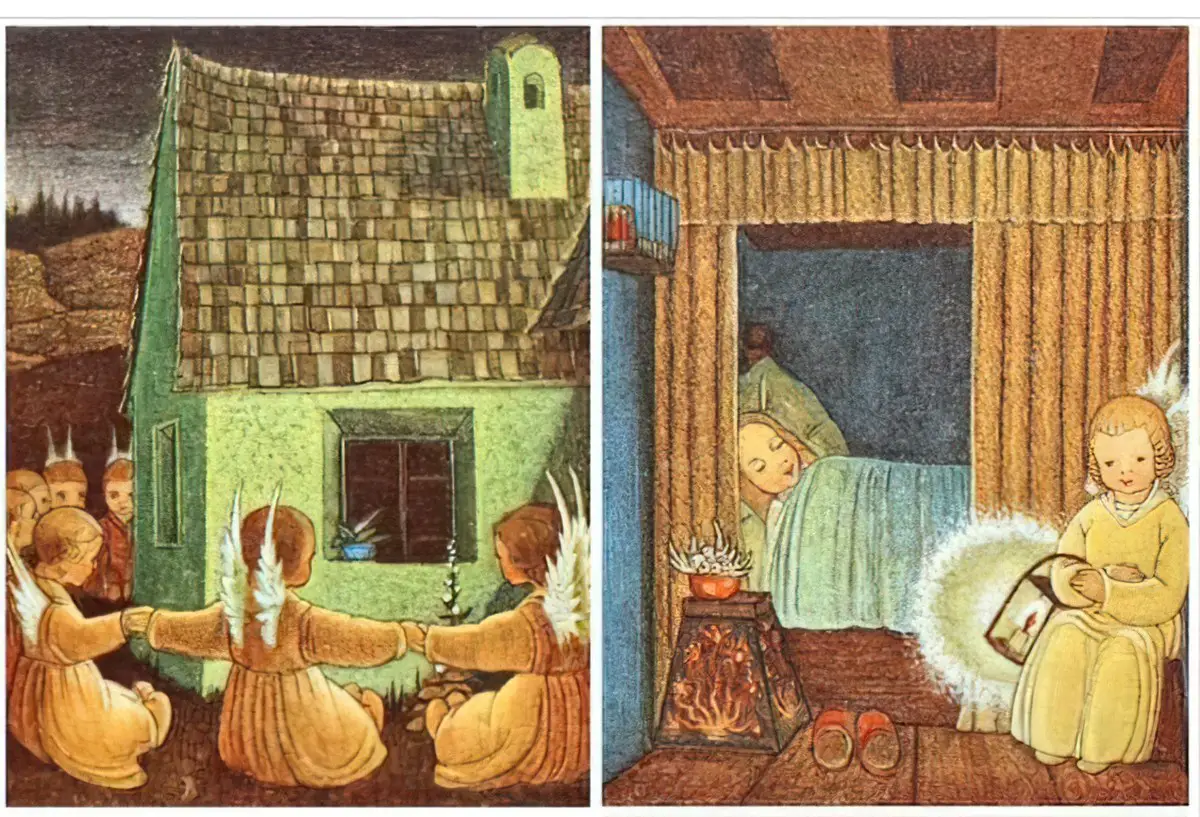

PRAYER

Instead of responding emotionally, the bereaved may jump straight to praying. They pray to a particular saint for a miracle. In many of these stories, preparations for the dead body have begun while the parents pray for a miracle.

In every miracle story, someone related to the dying child prays to a saint. Perhaps this is not a direct prayer, but a way of thinking. In the Medieval era, the practice of using your mind to voice another prayer while reciting a standard prayer was recommended.

Who to direct a prayer to?

Sometimes before the prayer there is a lot-casting scene in which the characters learn which Saint may step in to help. All of this can be doing without a church leader in attendance. This is lay people’s business. Religious people had use of texts such as ars moriendi (a manual for dying which was popular back then) but laypeople constructed their own prayers to use at time of death.

VOTIVE PROMISES

Parents make a votive promise. (“Bring our child back to life and we will give God this, do this for God…) A bargain.

Notably absent

Although people know that God can grant miracles as he pleases, they don’t complain to him that their child’s life was too short or accuse him of taking their child when he shouldn’t. It is accepted that death is part of God’s mysterious plan. (I also wonder if this is avoided – in the stories, at least – on the assumption you don’t throw accusation at someone from whom you need a big favour.)

MIRACLE OCCURS

Biblical miracles are immediate and quick.

The child comes back to life.

But Medieval miracles are a lengthy process. They don’t happen in an instant. Life may be regained limb by limb. Infants are the exception to gradual resurrection: they immediately start suckling again.

This part of the story often drills down on specific detail with the purpose of creating believability: names of witnesses, specific villages, occupations of those present etc.

MIRACLE AFTERMATH

In the stories of Medieval miracles, the parents have to carry out their promises to the saint before they get their kid revived. In miracle stories, parents always follow through on their promises.

REFERENCES

Cultures of Death and Dying in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

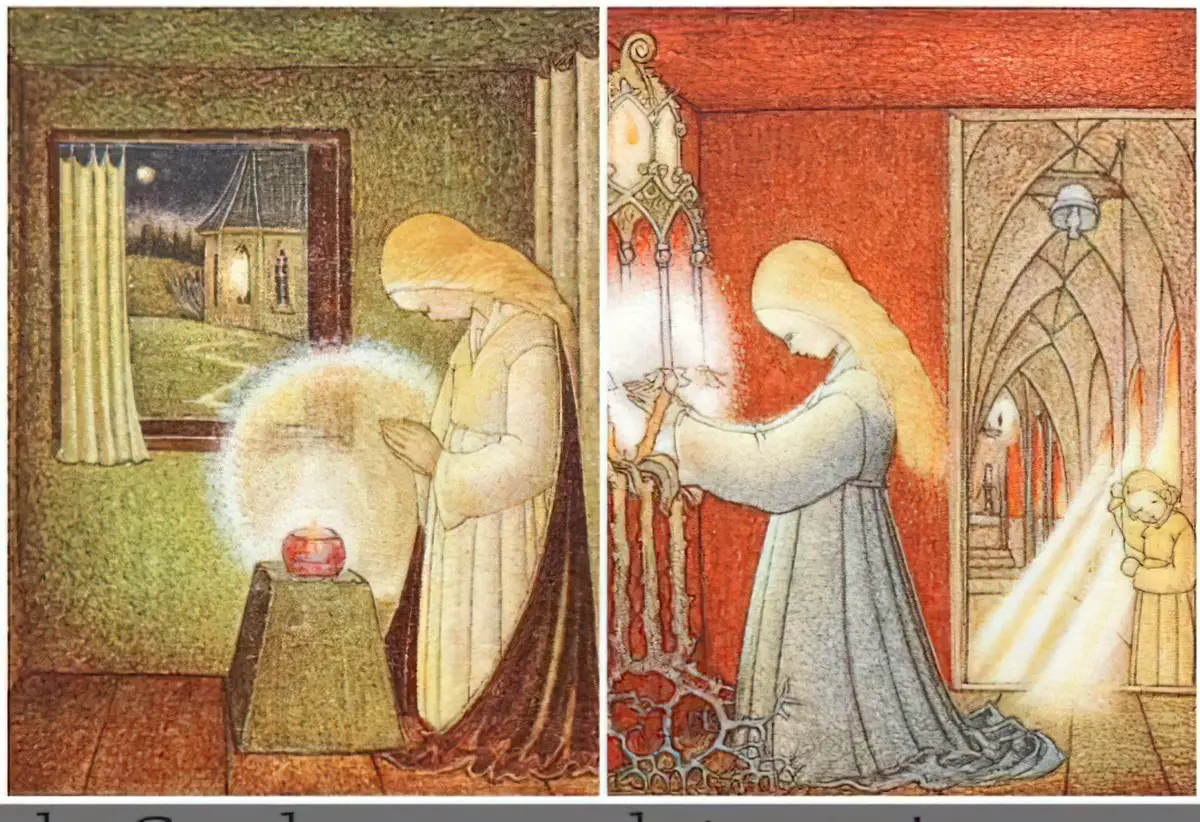

Header painting: The Miracle of the Gaderene Swine 1883 Briton Riviere 1840-1920