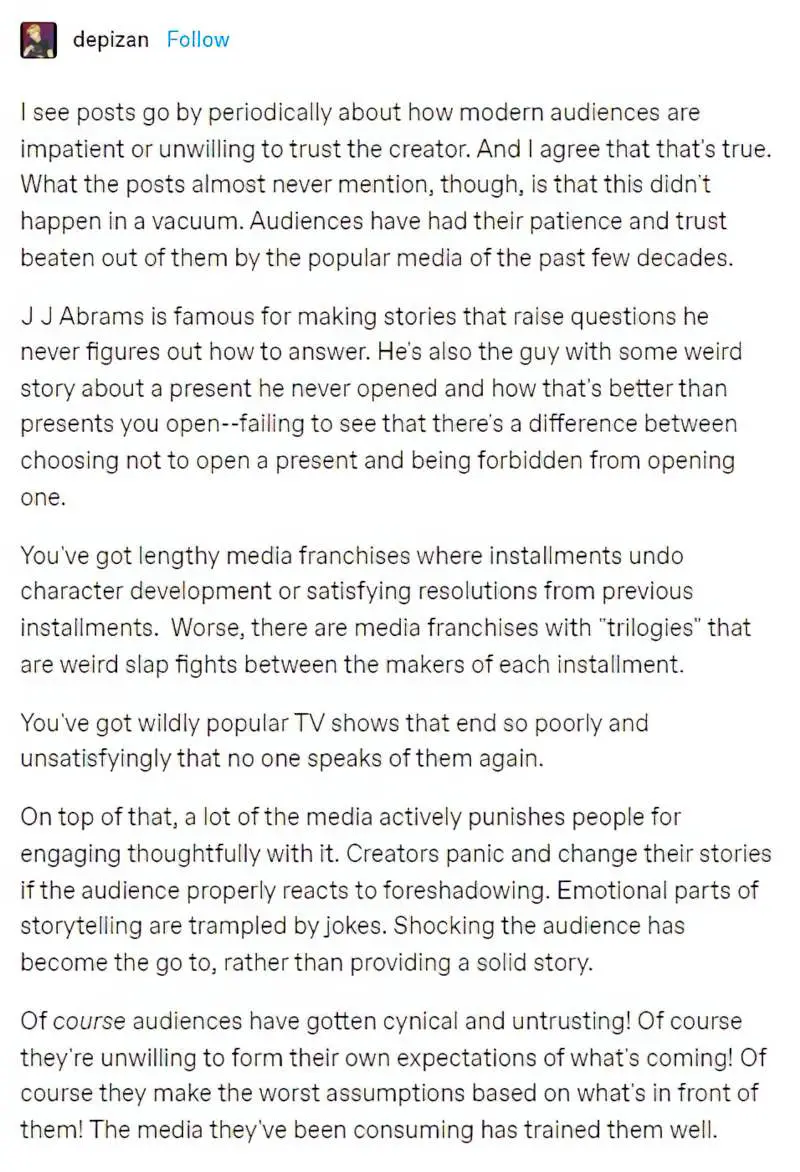

Mystery boxing is a storytelling technique which has only been accepted by popular audiences since about the year 2000. Back in 2000, the technique didn’t yet have a name.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MYSTERY BOXING

It is better to know some of the questions than all of the answers.

James Thurber

In 2007 J.J. Abrams gave a now-famous Ted Talk in which he spoke about stories as mystery boxes. The term is based on an actual, still-unopened mystery box of magic tricks his grandfather gave him as a boy. He didn’t want to open this box because the thought of what might be inside was more exciting than what was really inside.

The term ‘mystery boxing’ has since taken off as a way of talking about a certain kind of mystery in storytelling. Some people say it comes from the superhero comic tradition. (Others think it should stay there.)

Lost is the standout example. “Don’t worry about it [writers]. Just be profound.” Abrams says in his TED talk that sometimes “mystery is more important than knowledge.”

Mystery boxing was bound to take off once TV spoilers started to become a problem, at the turn of the millennium. Streaming services changed the way viewers watched shows, and in turn affected how writers created shows. Viewers were binge-watching entire shows over the course of a few nights, and were now able to spoil plots for their friends. Until the 21st century, everyone was watching live TV — the same show at the same time.

If a mystery is never really solved or explained in a story, the story can’t be spoiled, in a plot sense. In the age of mystery boxing, watercooler discussion around a popular TV show is going to be speculative rather than plot spoilery. However, mystery boxed shows create their own problems. If you tell someone to expect ‘a great twist’, they’ll watch the entire show with a certain expectation. Their experience will be altered. If you tell them about a twist which isn’t even there, this also alters the experience of immersion. In both cases, the friend is less likely to live in the moment of the story as it plays out.

Taking Abrams’ lead, other writers seem to have decided that, hey, actually, mystery boxing is a good idea. Audiences love it. Doesn’t matter if the show peters out; the fact is, we got them to watch X number of hours, and that’s good enough for Netflix rankings.

The cynic in me wonders if J.J. Abrams invented the concept of ‘mystery boxing’ to absolve himself of the fact he never really did flesh out the plot of Lost, despite successfully persuading a large audience of fans to invest many, many hours in that show. David Lynch is another creator who mystery boxes.

SMOKE MONSTERS

Because Lost is the tentpole example of mystery boxing, and because The Island of Lost is home to a mysterious entity, consisting of a black mass accompanied by mechanical-like sounds and electrical activity within, dubbed the “Smoke Monster” or just the “Monster” by the survivors, the term “Smoke Monster” is now sometimes used to refer more broadly to this kind of mystery opponent.

AN EXPANDED DEFINITION OF MYSTERY BOXING

Some writers simply forget to tie up the loose ends of their mysteries. Others start with good intentions and then completely lose the plot, writing themselves into a hole. That’s not what mystery boxing is. Mystery boxing is ostensibly deliberate. The writer is withholding information intentionally, for the purpose of getting the audience imagination to work overtime. As active participants in finishing the story, the audience literally creates part of the narrative themselves.

In his definition of mystery boxing, J.J. Abrams includes the age-old technique of leaving an item of interest partially ‘off the page’. Artists have been doing this for centuries. Abrams reminds us that the shark in Jaws is terrifying precisely because we never see the entire thing. (If we did, we’d laugh at the animatronics.)

I personally think Abrams was trying to incorporate this age-old technique into his theory of mystery boxing to make it more grand, and to excuse writers of pulling a trick which is really quite different. It’s one thing to ‘not show the shark’. It’s quite another thing to never explain how a ‘shark’ (Minotaur opponent) even works within the world of the story.

Abrams stretches the paradigm even further by talking about what the audience thinks they’re getting and what they’re really getting. He gives the example of E.T.

What audiences think they’re getting: A movie about an alien who meets a kid.

What audiences really get: A movie about divorce.

Here he is saying that the most successful stories are character based. This is something many people have observed. He doesn’t circle back to how this relates to the rest of his mystery boxing concept, but I deduce he means this: Audiences love the surprise of getting something in their ‘box’ (movie) that wasn’t in the epitext (the marketing material, or what their friends told them was in there).

Others have said similar things.

Characters that raise more questions than answers have a longer shelf life.

Paul Schrader

Film director Paul Schrader goes on to explain what he means in an interview at Writers Guild of America West:

The trick of that is, you present the viewer with only one view of reality, and that is the reality of your main character. And you use narration to get under their skin, to manipulate them subconsciously. And you keep them along this path for, I would say, at least 45 minutes to an hour. Then the hook is firmly planted in and the character can start to veer off, they start to veer away. They start to do things that are not necessarily worthy of your empathy or identification, but now the hook is in, so you’re wondering how it will turn out. In the end, you find yourself identifying with a character for whom you feel no cause for identification.

So you’re almost like an unwitting, guilty accomplice?

Yeah, and what happens there, is a tiny fissure opens up in the viewer—either in their head or in their heart—and something has to escape, or something has to come in. The artist cannot really control all the specifics [of this reaction], but if the artist causes this fissure to exist, he knows something exciting is going to happen.

In the case of Jaws, friends were likely to recommend the film by telling you about the shark parts; they’re unlikely to have told you it’s also about a father finding his place in the world and wrestling with the expectations of masculinity.

This aspect of Abrams’ definition of ‘mystery box’ is not the part of the definition which seems to have taken off. Now, when I see people talk about ‘mystery boxing’ they’re talking about what happened with Lost: a massive mystery running the length of a TV series which the showrunners never tie up.

MARE OF EASTTOWN AS AN EXAMPLE OF ‘PUZZLE BOXING’

In a review at the LA Times, Aaron Brady offers an excellent and thought-provoking analysis of Mare of Easstown. Don’t read it unless you’ve seen the show, but I offer no spoilers here; what’s interesting is his use of ‘mystery boxing’ to describe a cop show which is partly ‘whodunnit’ but mostly ‘portrait of all the other problems in a small town:

In the end, Mare of Easttown turned out to be a cop show. A strange cop show, always almost thinking unthinkable things about what cops are for and might be, but a cop show all the same. This generic revelation was a far more consequential one than the question of who did it… If the show was structured as a mystery, however, that whodunnit that kept you watching, week after week — as a new potential killer was gestured towards and then, in the next episode, shown not to be the killer — might have been the biggest red herring of all. The most interesting thing about Mare of Easttown is not the puzzle box question of who did it.

Aaron Brady

It seems the word ‘puzzle boxing’ is a cousin of ‘mystery boxing’. What does he mean by a puzzle box question? He means the answer to the question: “Who’s the murderer?” is functioning like a McGuffin to get the story going. The answer to that question isn’t as interesting as all of the other problems the investigation unveils.

MYSTERY BOXING AND LYRICAL SHORT STORIES

Readers of lyrical short stories are good at contributing to a plot and filling in gaps themselves. They are good at extrapolation. Whereas genre TV has become famous for mystery boxing, ironically, it’s the literary short stories (not the genre ones) which are famous for requiring readers to finish off the plot.

Other readers have no time for lyrical short stories. Those readers are easy to spot because they’ll say things like, “It’s not finished!” or “Nothing happens!”

Commentators who study short stories have come up with a number of academic terms to describe stories in which the audience is expected to come up with part of the story themselves. The most useful and easy-to-understand terminology, in my opinion, comes from Charles May, who talks about ‘dramatic’ versus ‘aesthetic’ closure.

Dramatic closure tidies up the plot. (Another term we might use is hermeneutic closure.)

Aesthetic closure leaves the plot open, but still manages to leave the audience with the feeling of complete evacuation. (I may be talking about constipation, now, but I think that’s a good analogy.)

Here’s a tweet from someone who I suspect likes the challenge of finishing off his own stories:

And here is a response typically heard from audiences who prefer mysteries and plots tidied up:

PROBLEMS WITH MYSTERY BOXING

Some audiences are never going to enjoy mystery boxing. They prefer their stories tied up in all the different ways, and will feel their time has been wasted unless they are given a conclusion to every plot thread.

How do you like your ghosts? Supernatural fiction is arguably the hardest to get right. Ideally it should terrify, but what appals A might bore B and merely confuse C. The mechanics of apparition, however fanciful, must be internally consistent, and explanations kept simple. M.R. James excelled at giving his spectres agency and focus, but in some hands ambiguity is more effective. Read a Robert Aickman and half the time you have no idea what happened, if indeed anything did.

Suzi Feay at The Spectator

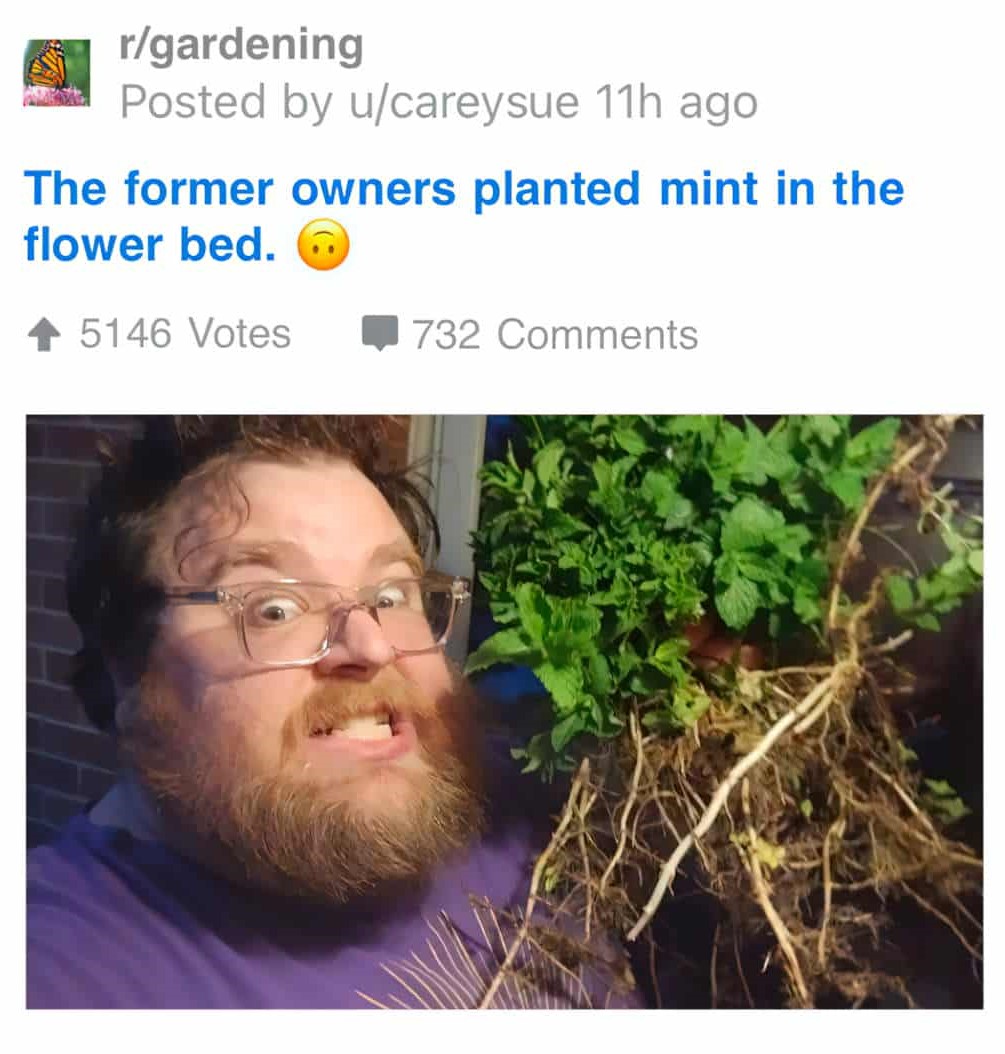

We are now at a point in popular storytelling where mystery boxing is common. And critics have started to get sick of it. In relation to WandaVision (specifically, the whole existence of Westview), Alisha Grauso had this to say:

Mystery boxing has killed modern audiences’ collective ability to read narratives and understand where they’re going and where they’re not….mystery boxing has absolutely overrun genre storytelling like an invasive plant species & mystery for the sake of mystery too often obscures everything else now. It’s not good.

Alisha Grauso, Features Editor at Screen Rant

RELATED WORDS

Writers and commentators have been talking about foreshadowing for a long time already. So one word is ‘foreshadowing’, which is pretty commonly known.

TELEGRAPHING

Telegraphing happens when foreshadowing falls flat, because the audience can see exactly what’s coming (when they were only meant to get a hint).

DELAYED DECODING

Delayed decoding is an academic term to describe the experience of reading a literary work twice, and getting a different experience because you now see the relevance of details dropped into the text. (This is why lyrical short stories need to be read at least twice.)

PROLEPSIS

Prolepsis is a ten dollar word for foreshadowing but actually ‘foreshadowing’ is a better word to use because prolepsis had a number of slightly different meanings. Apart from ‘a flashforward’ in rhetoric it also means ‘a figure of speech in which the speaker raises an objection and then immediately answers it’. (It’s also a type of fly, from the genus of robber flies, I don’t know why. They feed on clown beetles and dung beetles, fyi.)

FURTHER READING

The Evolution of the Mystery Box from Film Rejects, who argue that Westworld is similar to Lost in its use of mystery boxing, but learned from some of its mistakes. Other shows, such as The Good Place, have learned how to keep their twists organic.

Another example of ‘puzzle box’ used instead of ‘mystery box’: WandaVision’s Marvel Cinematic Universe roots undercut its puzzle-box ambitions from AV Club.