Which mouse are you? Fight, flight, freeze or appease? Beatrix Potter’s Mrs. Tittlemouse (1910) is inclined to appease, as perhaps you must, if you are small and vulnerable.

Except every mouse I have ever met is a bolshy, ‘sit on this and swivel’ type. In winter they hang out behind the dishwasher and will hurtle their brown little bodies across the kitchen, even with me, the rightful inhabitant, standing right there. Contrary to literary depictions, mice are definitely not the appeasing type. A realistic personification of mice would render them stunt doubles and heist criminals.

But what of Mrs. Tittlemouse? Mrs. Tittlemouse is the 1910 epitome of the perfect, uncomplaining housewife. She is also the epitome of a partner violence victim.

Just as rapport-building has a good reputation, explicitness applied by women in this culture has a terrible reputation. A woman who is clear and precise is viewed as cold, or a bitch, or both. A woman is expected, first and foremost, to respond to every communication from a man. And the response is expected to be one of willingness and attentiveness. It is considered attractive if she is a bit uncertain (the opposite of explicit). Women are expected to be warm and open, and in the context of approaches from male strangers, warmth lengthens the encounter, raises his expectations, increases his investment, and, at best, wastes time. At worst, it serves the man who has sinister intent by providing much of the information he will need to evaluate and then control his prospective victim.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

So do I approach this story like it’s 1910 or like it’s 2019? Well, let’s not be boring. Let’s see how this story from the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature has fared.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MRS. TITTLEMOUSE

Mrs. Tittlemouse is a classic domestic story, which were aimed at girls — not exclusively read by girls, of course. Stories aimed at boys tended to be adventures in which the boy character left the home, had fun away from the home, then returned at the end.

SHORTCOMING

The Shortcoming of every single mouse in children’s literature ever (well, not quite) is: smallness, shortcoming, vulnerability. The mouse is the animal stand-in for the child. Within that archetype there are many variations, but vulnerability is the standout feature.

Morally, there’s no fault on the part of Mrs. Thomasina Tittlemouse. There is nothing in this tale which sees Mrs. Tittlemouse treating another creature badly. That’s exactly what makes the story boring. Not all main characters of children’s stories have a moral shortcoming, but the most interesting ones do.

Important: Mrs. Tittlemouse’s ‘kindness’ towards her intruders is a survival strategy:

Niceness is a decision, a strategy of social interaction; it is not a character trait.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

DESIRE

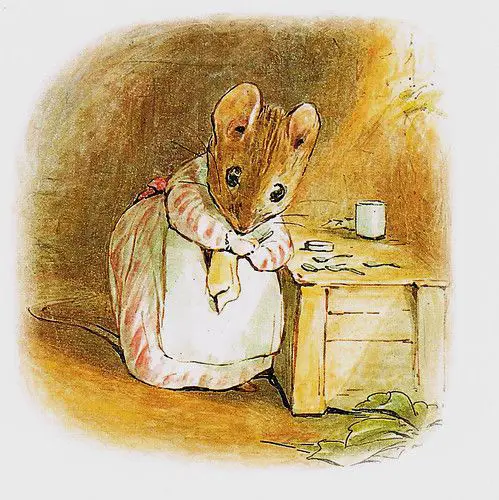

Mrs. Tittlemouse is a homebody who only wants to keep her house clean and tidy.

What does Mr. Jackson want? He wants her attention. He wants her labour, her material store, her living space. He wants to intrude; he wants her to notice him.

OPPONENT

Mrs. Tittlemouse’s opponents comprise the various creatures who come into her dwelling, creating chaos and messing up her good work. In they come, one after another:

- Beetles

- Ladybirds

- A big fat spider (who mistakenly thinks the house belongs to Miss Muffet).

Notice how Beatrix Potter has made use of the Rule of Three in Storytelling. As usual she got a bit of intertextuality in there, with reference to the nursery rhyme:

Little miss Muffet she sat on her tuffet, eating her curds eating and whey

Along came a spider who sat down beside her

And frightened miss Muffet away

Little miss Muffet she sat on her tuffet, eating her curds eating and whey

Along came a spider who sat down beside her

And frightened miss Muffet away

In his analysis of Little Miss Muffet, Albert Jack writes:

Pop Goes The Weasel

Arachnophobia is clearly not a modern compliant. Although cobwebs have traditionally been used as a dressing for wounds (and, scientifically tested, have turned out to contain all kinds of antibiotics), spiders have long been seen as malevolent. Richard III, presented by William Shakespeare as the most evil English king, is described as ‘a bottle spider’, which comes from the belief that spiders were inherently toxic — if one were dropped into a glass of water, every drop would be poisoned. It is therefore entirely understandable that this particular little girl from days gone by would have been frightened away by one…

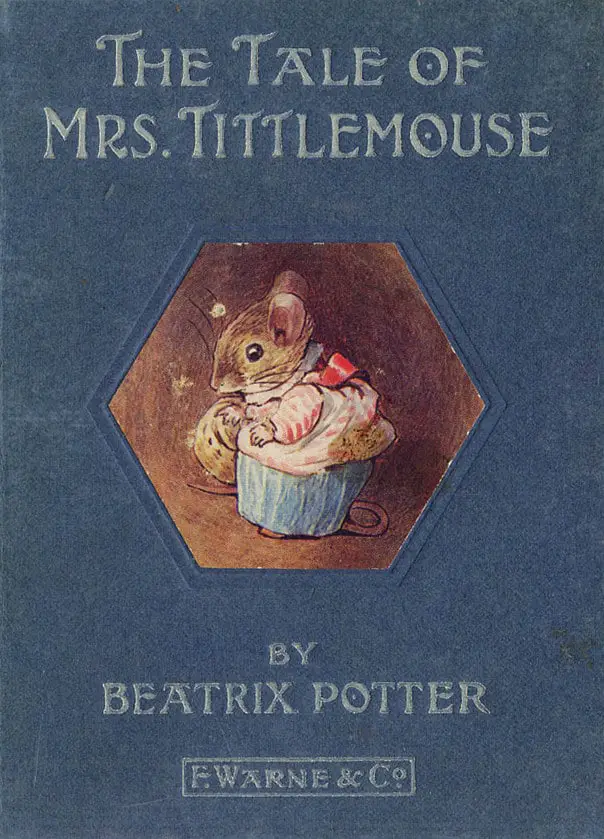

Beatrix Potter has subverted the trope of the scary spider in The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse, because the spider is not scary at all. In a story with a succession of opponents, some of these will at first appear to be opponents but will turn out to be benign, or possibly even mentors. (Otherwise a succession of baddies gets boring.)

Next come the bumble bees, and finally Mr. Jackson, the epitome of unwelcome guests. (Though is he entirely unexpected? Methinks he’s intruded before.)

Mrs. Tittlemouse know exactly who he is, but when we first meet Mr. Jackson he has his back to us, which makes him appropriately ominous.

Mr. Jackson’s shortcoming is that he doesn’t hear a woman’s ‘no’.

I’ve successfully lobbied and testified for stalking laws in several states, but I would trade them all for a high school class that would teach young men how to hear “no,” and teach young women that it’s all right to explicitly reject.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

PLAN

Mrs. Tittle mouse ‘bundles the spider out at the window’. Then she sets about getting dinner when she discovers her main opponent, Mr Jackson.

BIG STRUGGLE

Instead of telling him to get the hell out, Mrs. Tittlemouse gets on with pleasantries. She even offers him dinner. Then I suppose she wonders why he won’t leave.

Life is made up of challenges that cannot be solved but only accepted.

Roger Ebert

Mr. Jackson is a Cat In The Hat character (or maybe we should say it the other way round). The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse is now a carnivalesque comedy in which an intruder comes into a tidy house and creates havoc. He drips all over the place and blows thistle-down all over the room. He pokes through her cupboards in search of honey — he’s a bit of a Pooh Bear character.

Since Mrs. Tittlemouse is obsessed with tidying up, and therefore a boring character, Mr. Jackson meets a variety of insect foes as he explores the mouse house.

As animals are wont to do, they eventually leave of their own accord. Mrs. Tittlemouse has been holed up all that time, waiting for them to get the hell out.

ANAGNORISIS

It is ultimately Mrs. Tittlemouse who becomes the trickster. She saves her own abode by fetching twigs and partly closing up the front door, before they can come back.

She seems to have realised that although her small size makes her vulnerable, she can also use this to her advantage.

Mrs. Tittlemouse also seems to have realised that she only enjoys the company of other mice — all turned-out nicely and with good table manners.

NEW SITUATION

Perhaps this story could not end in any other way, but when Mr. Jackson turns up, gatecrashing the mouse party, Mrs. Tittlemouse hands him acorn-cupfuls of honey-dew through the window even though her door is too small for him to come in.

This is a story of archetypal appeasement: A character ignores your boundaries, so you do the bare minimum to pacify them. You hope they won’t retaliate or become violent if only you give them a little.

This is terrible advice.

Mr. Jackson clearly understands he is not wanted, yet he demonstrates highly troubling persistence.

And so the story ends, and apparently all is well in the world. Everyone is happy. Mr. Jackson can still enjoy reciprocation from the target of his attention.

But with that jerk right outside, can Mrs. Tittlemouse be truly happy? Can she ever be truly free?

If you tell someone ten times that you don’t want to talk to him, you are talking to them—nine more times than you wanted to.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Pair this children’s picture book with “The Little Governess“, a modernist short story by Katherine Mansfield, likewise about a female character who is obliged to be ‘nice’ to a man who invades her space. In the case of the little governess, she is out on a mythic journey, but the case of Mrs. Tittlemouse shows another reality: Women don’t have to even leave their homes in order to suffer the imposition of entitled men. Therefore, it’s not up to the woman to take measures to avoid such men, such as avoiding public (male coded) spaces.

Certain animals are coded as industrious and others as lazy. Another animal coded as industrious when anthropomorphised is of course the bee.