Beatrix Potter wrote Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle specifically to appeal to girls. She thought that Lucie’s feminine garb, with its emphasis on the lost clothing items (o, calamity!), would appeal to girls especially.

Even today, authors and publishers are creating children’s books for the gender binary* e.g. this book will appeal to boys because X; this will appeal to girls because Y.

*Gender binary is not an ideal term, though it’s used widely. We don’t live in a gender binary — that suggests two categories which are equal. We live with gender isomorphism, in which there are ‘men’ and ‘failed men’.

Potter’s concept was a hard sell — publisher Norman Warne (about to become her fiancé) couldn’t see the appeal but he must’ve conceded he wasn’t a girl himself so Beatrix would know better, and Beatrix won (as she often did).

But Beatrix was wrong about the appeal of Lucie. Everyone who sets out to write ‘boy books’ and ‘girl books’ is always completely wrong, of course. Lucie didn’t garner much of an audience at all — everyone preferred the character of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle.

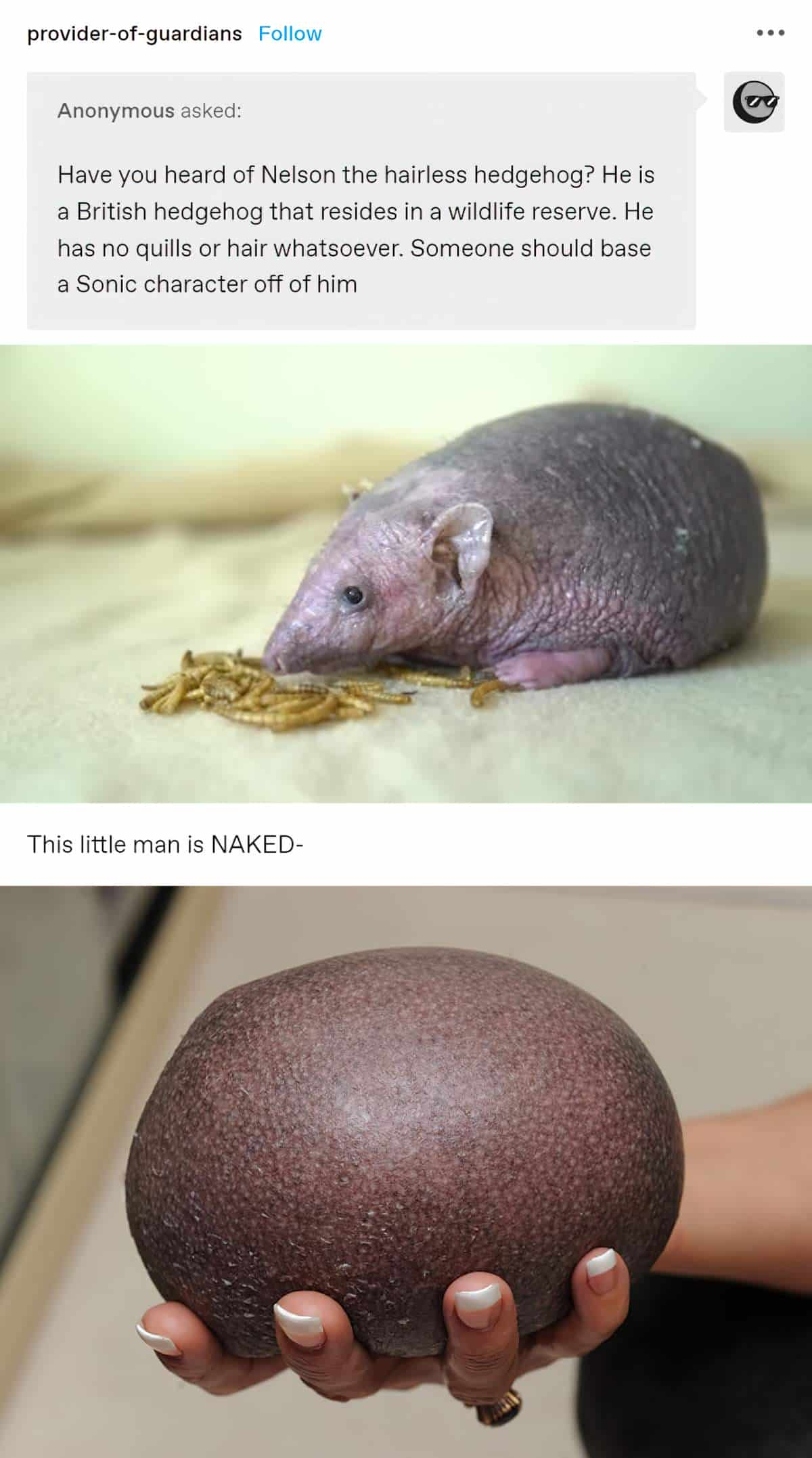

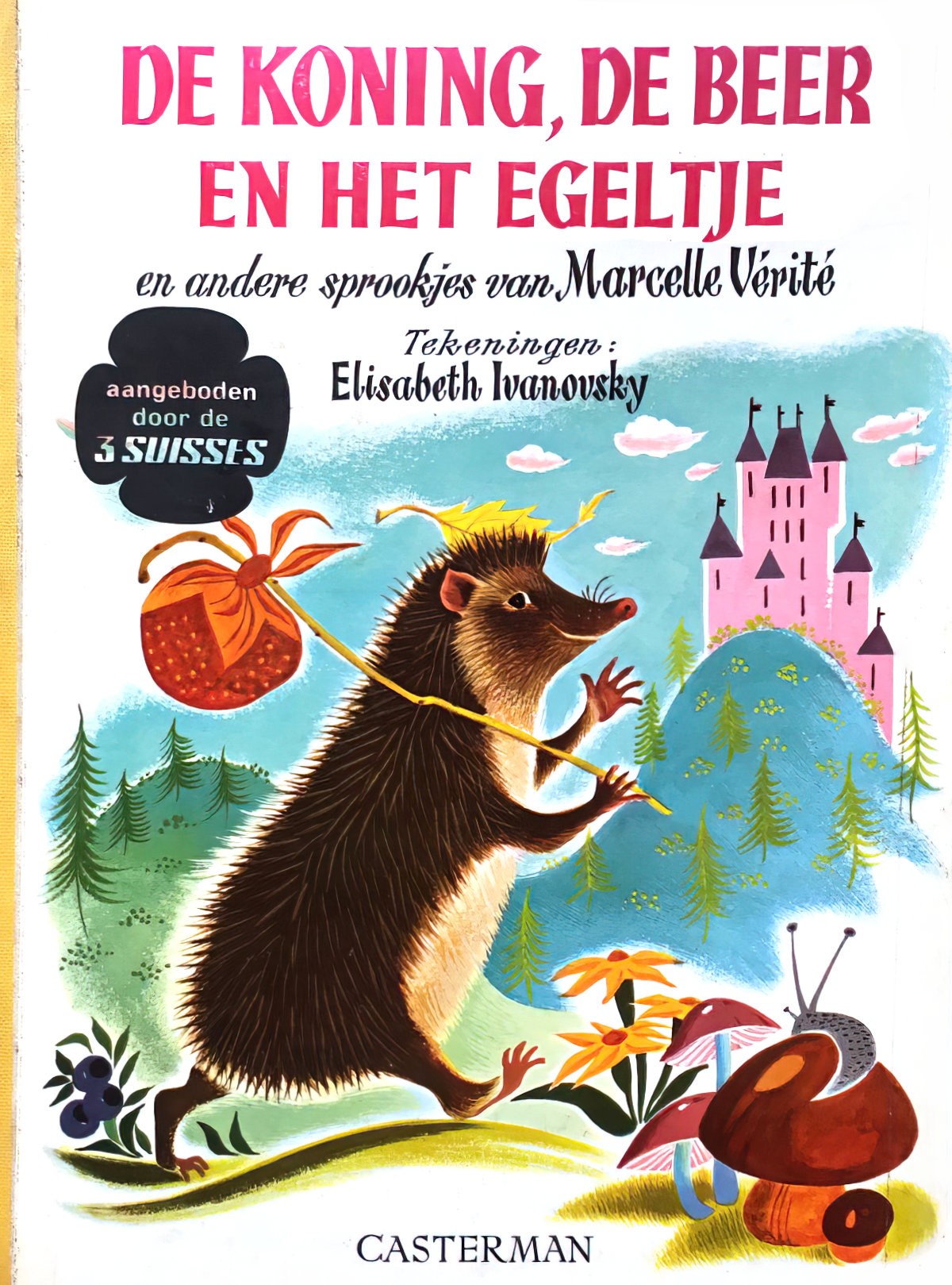

Norman hadn’t been keen on a ‘hedgehog book’, either. He didn’t think dirty hedgehogs would appeal to kids — probably because they’re not fluffy. (The spines are modified hairs, Norman.)

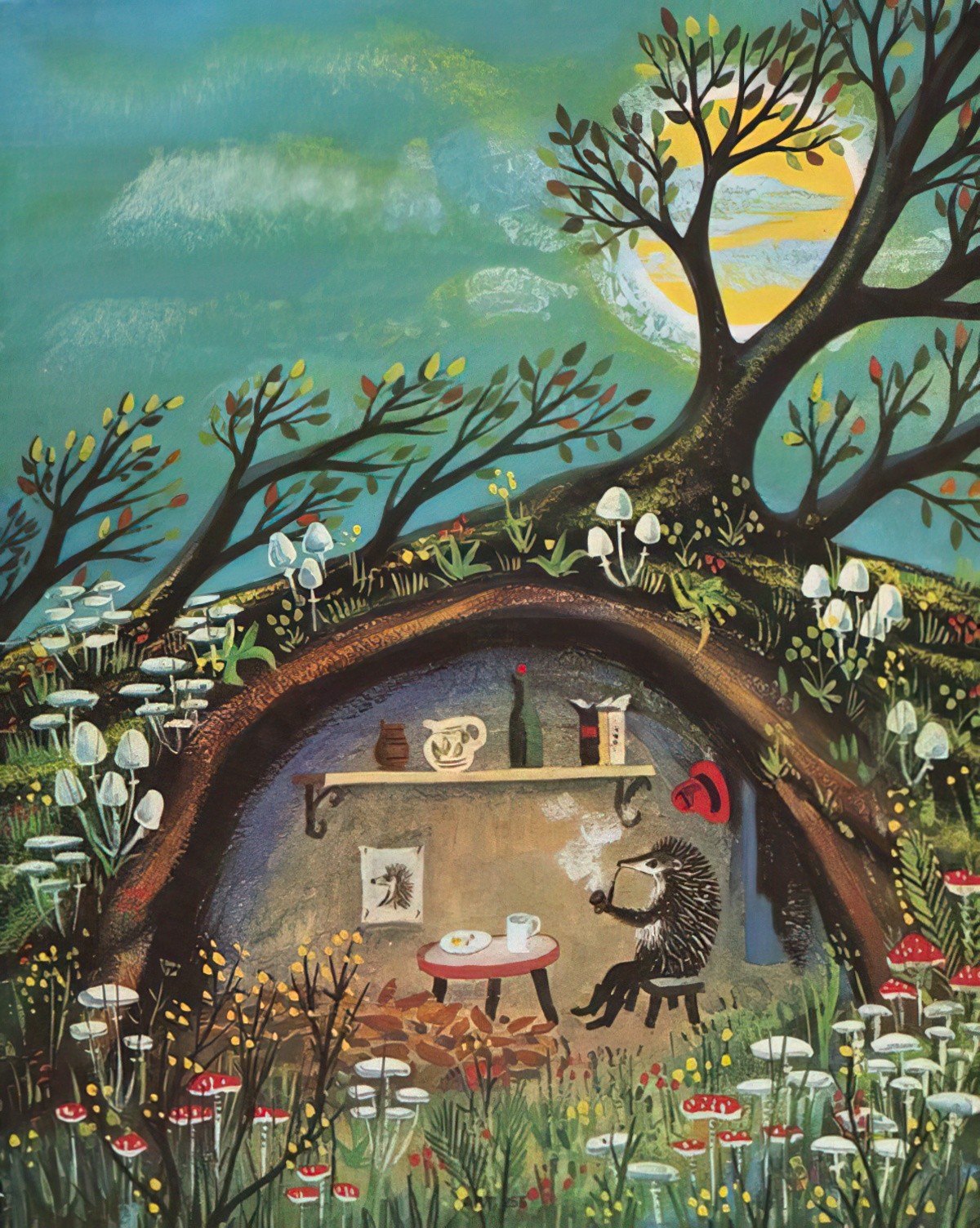

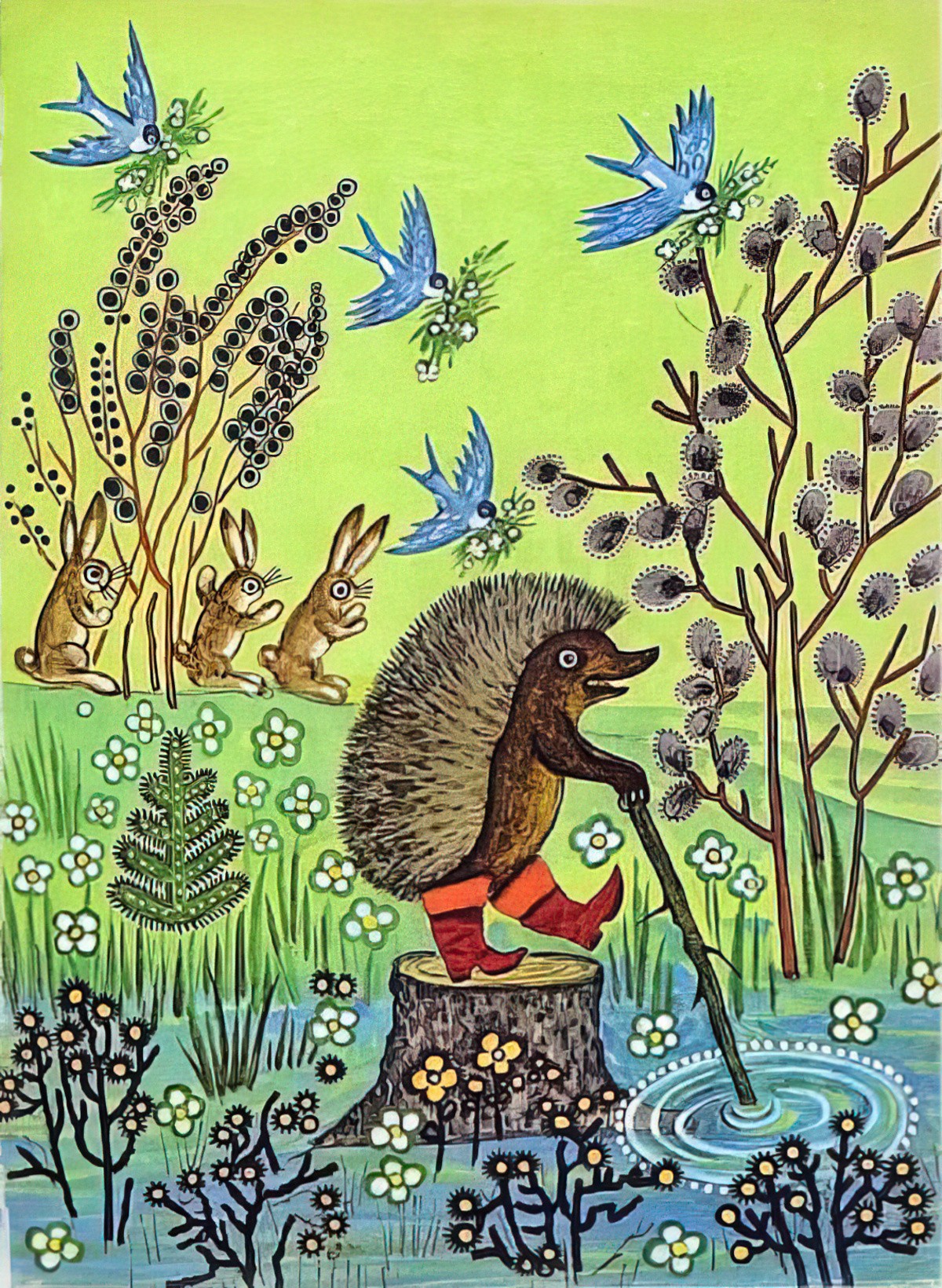

Perhaps it was Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle herself who paved the way for an entire raft of animal children’s books featuring non-cute creatures. Now we see reptiles, naked mole rats, fish, likeable insects and almost anything you can think of in picture books.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MRS. TIGGY WINKLE

Since Potter intended Lucie to be the main character, that’s where I’ll go with it.

SHORTCOMING

Lucie’s shortcoming is that she keeps losing things.

DESIRE

Lucie wants her handkerchief and pinnies back, which sets her out on her journey.

OPPONENT

This is a carnivalesque story, so the Opponent is replaced by a fun creature who allows the child to enter fully into a world of fantasy.

Any sense of danger comes only from the ‘hair-pins’ poking through Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle’s bonnet, wrong end out. This suggests she could snap at any time… though she doesn’t, of course! She’s a working class woman and remains deferential to Lucie, who comes from a middle-class household. (Back then it was very easy to tell socio-economic status from clothing.)

Although I’m sure most readers won’t bring the story of Chicken Little to front-of-mind when reading Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, Chicken Little exists in a corpus of scary folk and fairy tales in which children go off looking for something, enter a wild creature’s house and come to a messy end. Goldilocks and The Three Bears is another example. So with those tales as palimpsest, there’s an ominous atmosphere to Potter’s Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, despite the fact that Lucie is always very safe with the hedgehog, despite her dagger-like spines.

PLAN

There are elements of many classic tales here, not only Chicken Licken, which involves a character going from character to character asking the same question. (Also birds. Lots of birds.) In this case Lucie is looking for her handkerchief as a kind of McGuffin. (Not technically, because she does get her things back at the end.)

Jon Klassen uses a similar story structure in I Want My Hat Back.

Eventually Lucie’s plan is to follow a particular bird, who appears to be leading her somewhere — to the top of a hill where she has a revelation. See: The Symbolism of Altitude.

Potter is also making use of the Miniature in Storytelling technique, starting when it appears Lucie can drop a pebble down a chimney, even from the top of a hill. This is describing how Little-town looks tiny from the elevated vantage point, like a dollhouse. She is about to enter a world of play.

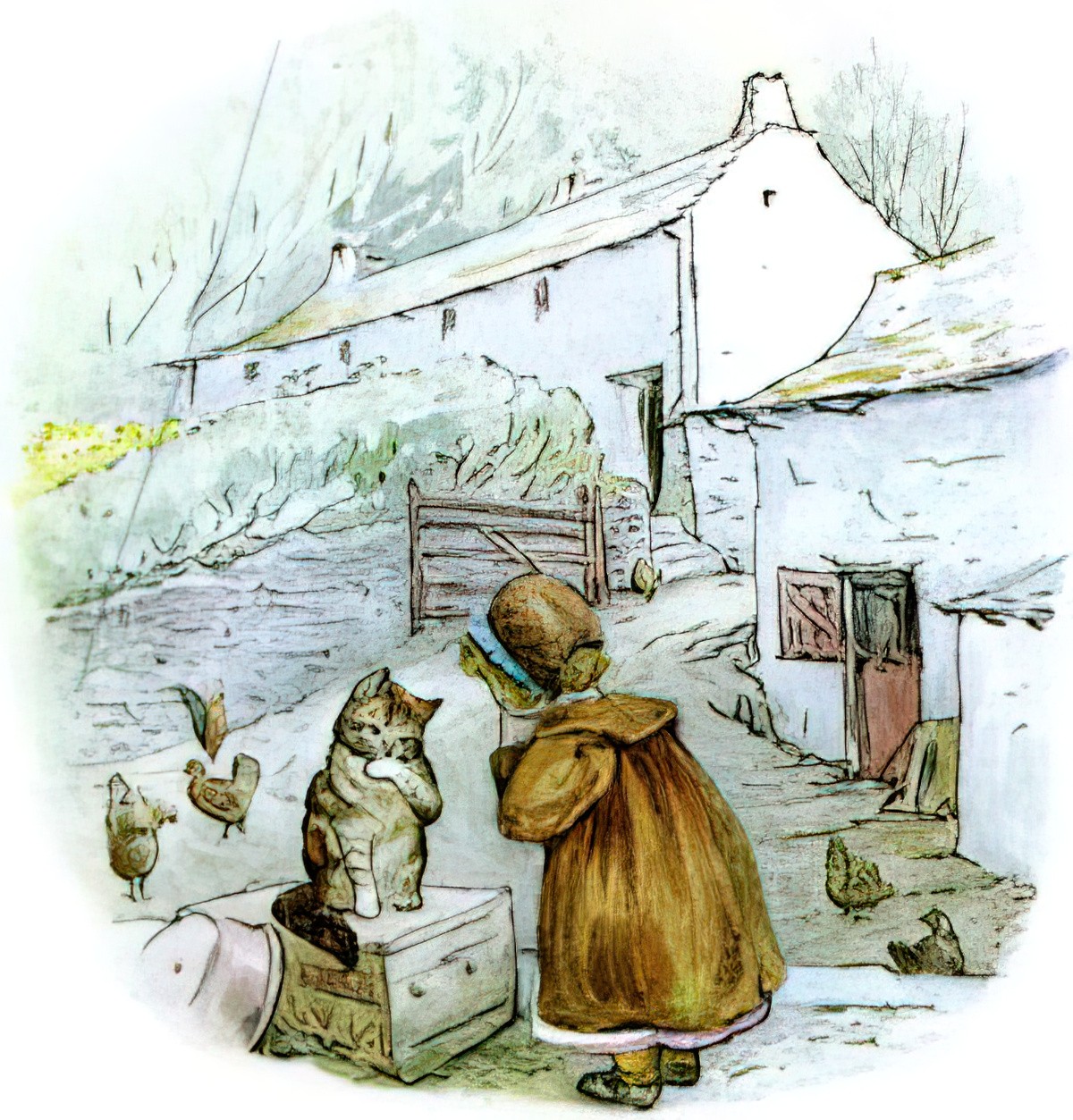

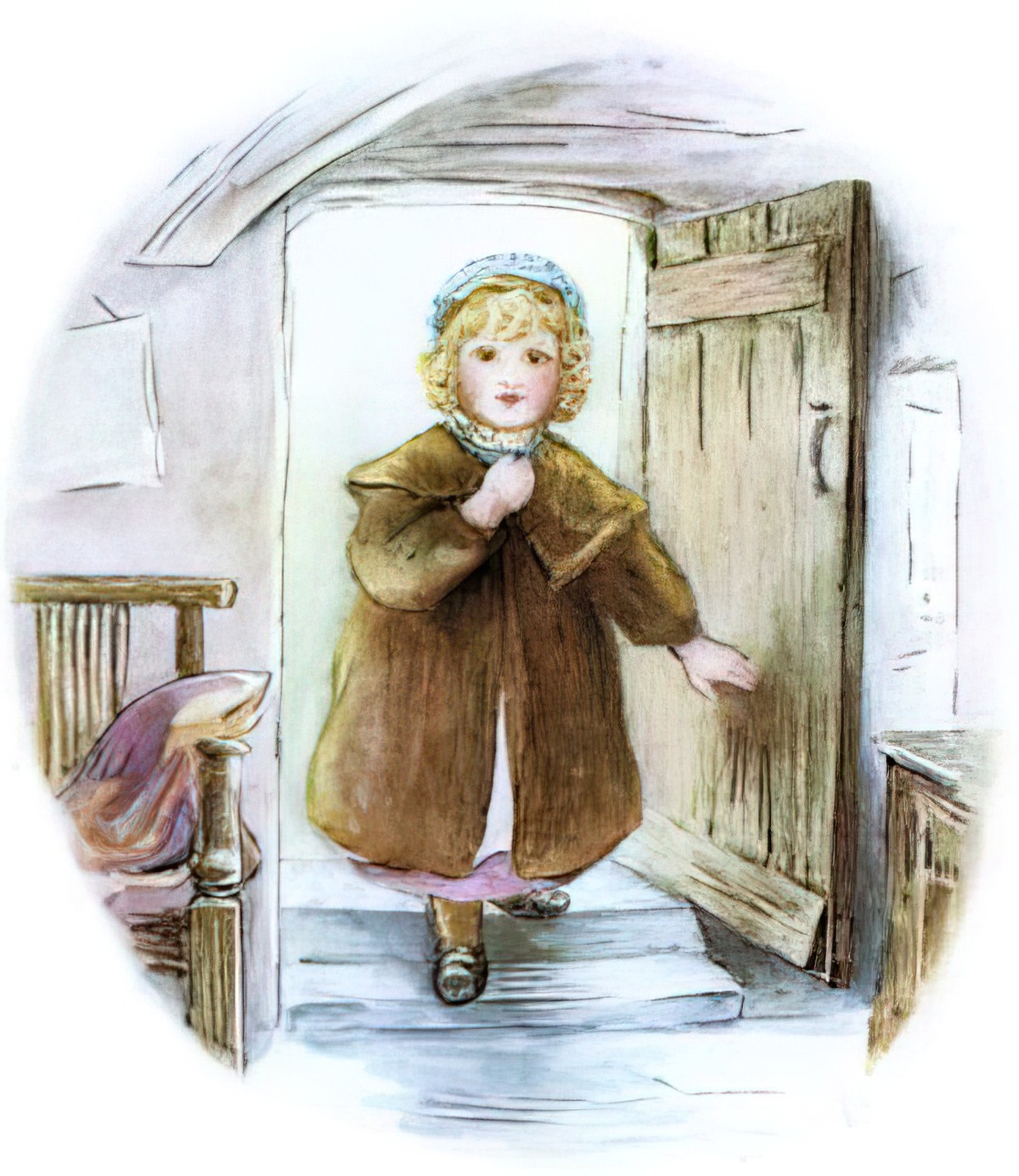

When Lucie finds the footprints she follows them, almost in spite of herself. This has the vibe of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland — she eventually finds a portal — not a rabbit hole but a door straight into the hill. (Pied Piper, anyone?) The Alice imagery continues when Lucie enters the hedgehog’s house and seems to shrink, though she hasn’t literally changed size within the setting — it’s just that the ceiling is low and everything is in miniature. This is the wish fulfilment fantasy of shrinking down and entering your own dollhouse. I can imagine this appealed, though not just to girls.

BIG STRUGGLE

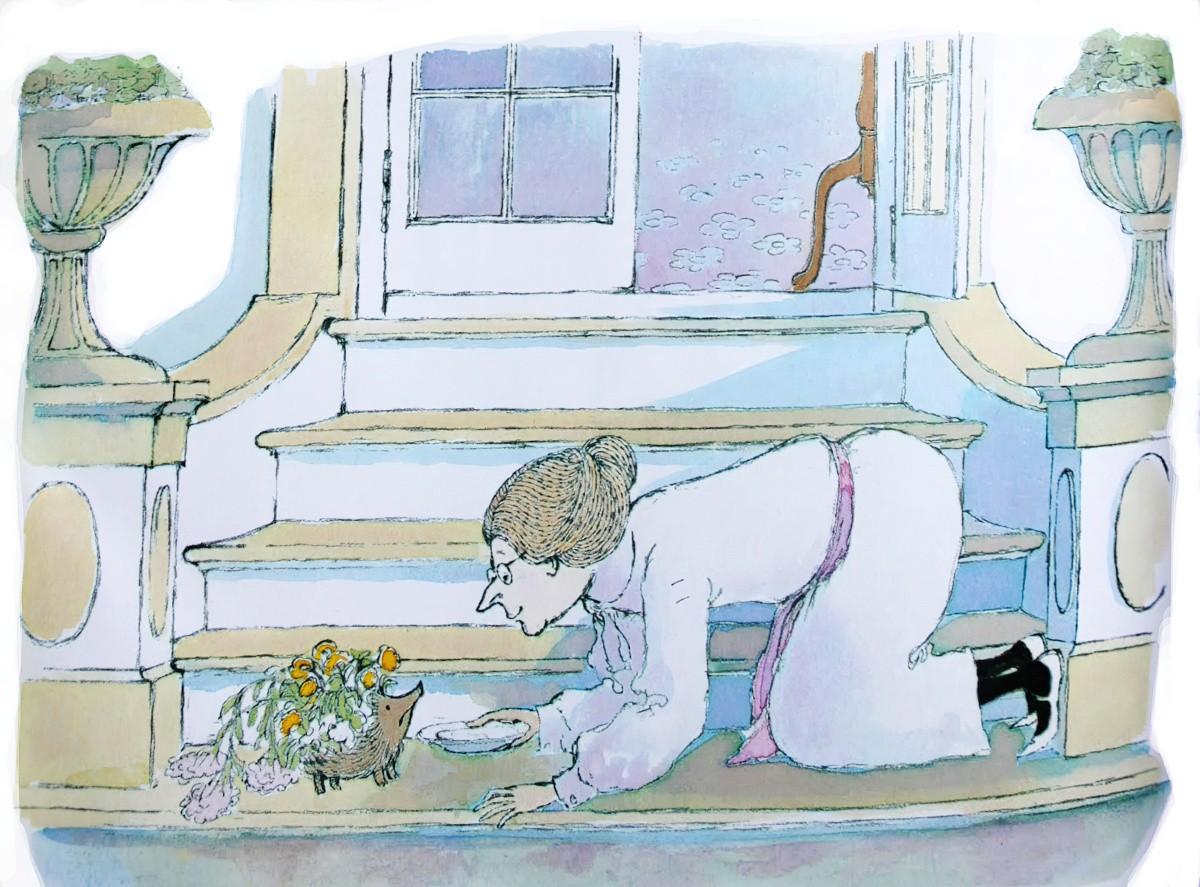

Although this story begins as a mythic journey, Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle is still a pretty standard Domestic Story, set inside the home, with female characters doing feminine things. But because this is a hedgehog washer-woman, this alone is enough to thrill the young audience of its era, and the carnivalesque ‘fun’ involves watching Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle wash clothing items belonging to a variety of woodland creatures.

When Lucie is excited to meet Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny, this is a clear early example of intertextual marketing. You’ll see the same thing done today. For instance, some of the later Babymouse books make sure to mention the authors’ ‘boy book’ companion series about the amoeba.

Finally, the visit concludes when Lucie and Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle sit down and drink tea.

ANAGNORISIS

In a carnivalesque story like this, the Anagnorisis phase is replaced by a stage that marks the end of fun and passage back into the real world. In this case, the stile marks the portal back into the real world.

The inevitable message: Magic must be real. If you can imagine it, perhaps it might come true. Lucie realises this, and so might the reader.

NEW SITUATION

(Now some people say that little Lucie had been asleep upon the stile—but then how could she have found three clean pocket-handkins and a pinny, pinned with a silver safety-pin?

And besides—I have seen that door into the back of the hill called Cat Bells—and besides I am very well acquainted with dear Mrs. Tiggy-winkle!)

Mrs Tiggy-Winkle is an early example of what TV Tropes calls “Or Was It A Dream?” Potter is very clear about what she’s doing, with a note at the end. These days the reader is given no such hand-holding. You see an example of this trope in a picture book like The Polar Express, in which the child seems to go off on a fantasy adventure but is left with a token of proof.