“Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” is a misogynist short story by British author Roald Dahl, and an excellent example of Hate Your Wife humour. You’ll find it in Dahl’s 1959 collection Kiss, Kiss. I call this story “Mean-spirited Gift of the Magi”.

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” was broadcast April 2011.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “MRS BIXBY AND THE COLONEL’S COAT”

A CHEATING WIFE

Once a month, Mrs Bixby tells her dentist husband she goes out of town to visit her aunt. But actually, she is visiting her secret lover. Whereas the lover is manly, the dentist is small and unmanly.

THE MEANING OF THE WET MOUTH

Mrs Bixby is described as having ‘a wet mouth’. I’m not sure what this means exactly, since having a wet mouth is surely better than having a ‘dry mouth’. (Aren’t mouths supposed to be wet?) I assume Dahl is referring to the lips area, and the lips are wet because the character has been licking them. Perhaps this describes the sin of lasciviousness.

I believe he is using “wet mouth” as an excessive version of “moist lips,” which would actually sound attractive. If he said “small, delicate girl with moist lips,” she might seem an ideal of young womanhood but Dahl says Mrs. Bixby appears excessive in her size and vigor and her entire wet mouth makes her very nearly repulsive compared to his unspoken ideal.

“A description of a woman”, in which I’m not the first to wonder about Mrs. Bixby’s ‘wet mouth’.

Note that Dahl frequently described mouths. The psychopathic bully in “The Swan” is described like this:

His mouth was loose, the lips often wet.

“The Swan”

In “Georgy Porgy” a vicar is kissed by a pushy older woman. He envisions her giant mouth coming at him:

“…and the mouth kept getting larger and larger, and then all at once it was right on top of me, huge and wet and cavernous, and the next second–I was inside it.”

“Georgy Porgy”

This is followed by a hallucination scene. The vicar imagines himself right inside the woman’s mouth, hanging onto her epiglottis.

THE GIFT OF A COAT AS BREAKUP GIFT

One day Mrs Bixby is due to meet her out-of-town lover but instead receives a gift box passed to her in person from one of her lover’s friends, who for some reason happens to be a ‘dwarf’. Delighted, she opens the gift in a toilet cubicle at the train station. It’s a super expensive mink coat. Worth thousands.

She reads the card. Unfortunately, this is her lover’s parting gift. For reasons he does not explain, he cannot see her ever again. Oh well, how sad, too bad, never mind. Mrs Bixby is shallow and interested in money. The narrator introduced the story by telling us that American women now have more money than the men, who are working themselves to death at their desks just to keep a hold of their demanding female partners. So Mrs Bixby is, typical for a gold-digging woman, delighted with the coat and not at all sad about the lover.

THE TRICKSTER HEIST PLOT

One problem: How can she possibly wear this fabulous coat without arousing suspicion? She hatches a plan.

Readers watch as she carries out her plan. First she pops in to a pawnbroker’s shop. She tells the pawnbroker she lost her purse and needs cash. She’ll be back to pick up the coat but in the meantime she requires fifty dollars. But no, don’t write her name on the ticket.

IS THE PAWNBROKER ALSO A TRICKSTER?

The pawnbroker reminds her — and also readers — that should she lose the ticket, anyone could come back and redeem it. Of course, this is exactly the point.

WE MEET AND HATE THE HUSBAND

Once back at home with her grumpy husband in their New York apartment, we see the couple together. The Colonel is a grumpy, unpleasant mansplainer.

Dahl picks low hanging fruit by making him a dentist. Dentists were widely despised before 21st century pain management.

Mrs Bixby feels justified about the cheating because he is also small and weak and ‘subsexual’, like a dandelion, a water flea, or Lewis Carroll.

Mrs Bixby explains to Colonel Bixby how she found a ticket with no name on it. The pair of them get excited. If the ticket says $50, the item will no doubt be worth much more than that. They should redeem it.

THE HUSBAND TURNS INTO A TRICKSTER

The husband insists on picking up the item himself, whatever it is. If it’s an item for a man, the husband will keep it. If it’s for a woman, the wife will keep it. This will suffice as a Christmas present.

Colonel Bixby calls Mrs Bixby from work to tell his wife she’ll love what he picked up. She goes to his office to collect her ‘surprise’.

The surprise is not what she hoped: The husband presents her with a mink neck piece, worth far less than the full coat. Moreover, this thing is gruesome. It was clearly once an animal. The animal parts are intact on a fur stole.

THE TWIST

Readers are now wondering if it was the pawnbroker who ripped off the husband, or the husband who ripped off his cheating wife. Next, the husband’s secretary comes out. The secretary is wearing Mrs Bixby’s mink coat.

We deduce that Colonel Bixby gave the coat to his secretary because he and his secretary are having an affair, just as Mrs Bixby was having an affair.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE COATS

I don’t really want to elevate this story by talking about the symbolism of coats. Others have pointed out that the husband and wife start out wearing a coat, which functions as a narrative mask. Here’s what we know about masks: They’re always removed before the end.

Sure enough, Mrs Bixby is stripped of her coat. We can deduce she’s been found out. Extrapolating this symbolism, I believe the husband knows exactly what his wife has been up to, and where the coat came from.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “MRS BIXBY AND THE COLONEL’S COAT”

- The first four paragraphs of “Mrs Bixby and the Colonels’ Coat” introduce a story-within-a-story. Who do you imagine is the character introducing the story? (Gender, age, generation?)

- If the metadiegetic level (the narrator’s introduction) of the story were simply crossed out, how might this story hit differently for the reader?

- Inventing things but presenting them as fact for the sake of story is from the tall tale tradition. Which facts has Dahl invented for the sake of the story, and what effect does this have 1. on the story itself 2. on the wider culture of people reading this story?

- What is the big revelation at the end? (The so-called ‘twist in the tale’)

- Would you say that Colonel and Mrs Bixby are ‘as bad as each other’? Does the story say anything about ‘women as a category’? ‘Men as a category’?

- When Mrs Bixby considers her husband ‘subsexual’, what is she talking about, exactly? How does she expect a man to be and, in her opinion, how is he failing? What has Lewis Carroll got to do with it? What might a contemporary reader say as an equivalent insult?

- Can you think of other Roald Dahl stories (for adults or for children) featuring spouses who can’t stand the sight of one another?

- Can you think of other popular narratives from the 20th century and earlier featuring spouses who can’t stand the sight of one another?

- What about 21st century examples? Do you think the ‘I Hate My Spouse’ gag is as prevalent in the 2020s as it once was? If not, what kind of humour has replaced it?

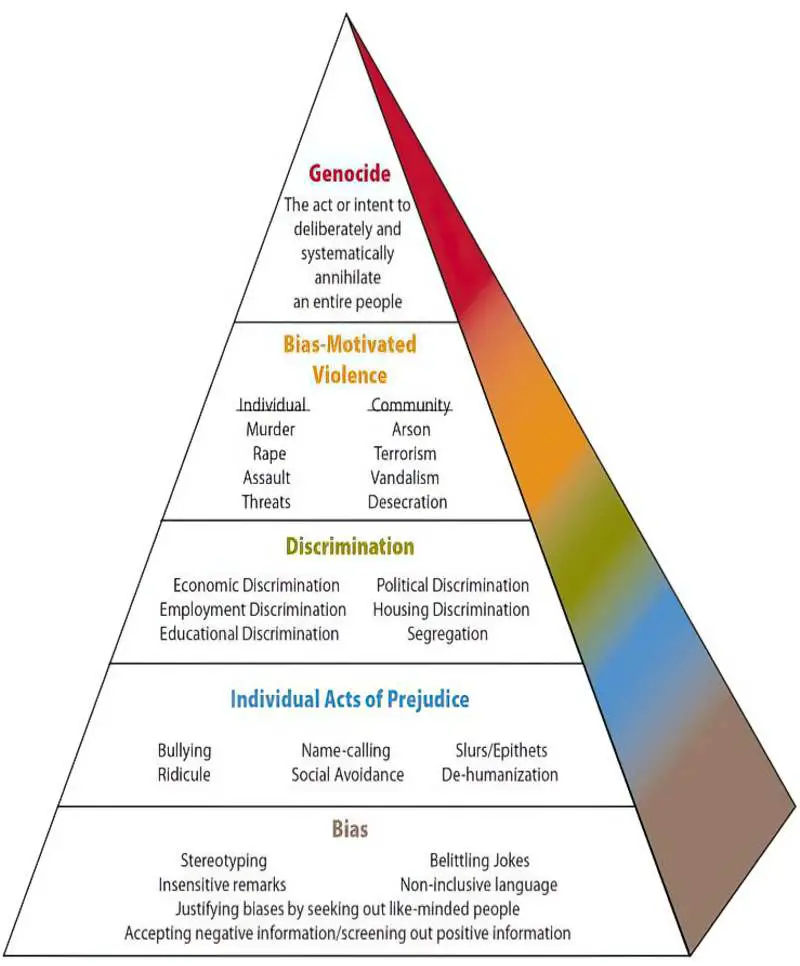

- If there were hypothetically no such thing in the world as misogyny, racism, LGBTQ+ phobia, ableism and general bigotry, what other types of currently popular humour would no longer garner an audience? Give an example.

THE PATRIARCHAL STORY-WITHIN-A-STORY TECHNIQUE

Patriarchs understand that their voices are heard over others’. When Washington Irving wrote Rip Van Winkle as a story-within-a-story he framed it as a learned and trustworthy man (trustworthy because he is a learned and trustworthy man) imparting the Word of God to his audience. The story he tells within that framing is one of misogyny, but the framing helps audiences to trust it.

“Rip Van Winkle” is frequently described as satire, and Roald Dahl’s story is an old Hate Your Wife joke turned into a short story, much as ancient oral fairytales were eventually written down (mostly by men, like the Grimms).

The lives of American women in the 1950s:

- Women still own far fewer assets compared to men, and this disparity was far worse in the 1950s.

- Women were not allowed credit cards in their own names. If they wanted a house loan, it needed to be co-signed by a man.

- Women were expected to work (for less pay) until marriage, but once pregnant, were frequently required to give up their jobs.

- A man was allowed to rape his wife. It was not called rape.

- Society turned a blind eye when it came to partner violence, which is strongly gendered.

Rule one of satire: You cannot meaningfully satirise positions so extreme any satire would be indistinguishable from people espousing those positions unironically. This is also known as The Rule of Clarity of Intent. Some positions and views make clarity of intent basically impossible.

You can’t satirise misogynistic men when the audience are misogynistic and you’re just describing what misogynists already think.

THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AROUND HATE-YOUR-WIFE JOKES

If you remember being alive in the 20th century, even towards the end of it, you’ve been soaking in hate-your-wife humour, a subcategory of so-called ‘boomer humour’.

We might call this humour ‘hate your spouse‘ rather than ‘wife‘ because it definitely works both ways. But, like other forms of violence, the joke is disproportionately directed at women — nagging wives (and, by extension, mothers-in-law). Whereas straight women do commiserate about husbands in private, “I hate my wife” is more culturally prevalent than “I hate my husband” because men had/have control over the general media narrative.

The “I hate my wife” trope is — and probably always has been — a way to be misogynist out loud and garner support for it.

- The Bible (Proverbs specifically) — nagging wives are like a dripping tap etc.

- Rip Van Winkle — See my post “Rip Van Winkle Can Get In The Sea“

- Pub yarns — Roald Dahl did not come up with this plot himself. He turned a popular pub yarn into a story.

- The Honeymooners — an American television sitcom which originally aired from 1955 to 1956, created by and starring Jackie Gleason.

- Rodney Dangerfield — here’s a compilation of his ‘my wife’ jokes

- I Love Lucy — Fred and Ethel’s relationship

- Married With Children — Peggy is so awful that she literally ruined Al’s life in high school by causing him to sustain a serious football injury. He plays the perpetual victim who is somehow unable to leave his horrible wife because she caused him to be pathetic, undesirable, and unable to earn an income because all he was good at football. Al Bundy is the poster child for “I hate my wife”.

- The Sonny & Cher Show

- Roseanne — Roseanne was weirdly progressive in many ways (and definitely not in others). Roseanne, the character, cracked many jokes about the problems of married life but overall seemed content about her family set up, ribbing her husband with a congenial smile rather than a sneer.

- Everybody Loves Raymond — except for those of us who hate his guts

At the end of the day, to me, the show is not at all about a toxic marriage. The show is about two women and how women can save each other.

Valerie Armstrong

“The Apple Tree” by Daphne du Maurier also has a Dahl-esque plot, come to think of it, except the wife has the last laugh, and Dahl never did manage to write a decent ghost story.

WHY HAS hate your spouse HUMOUR DIED?

- There is far less social pressure to remain in an unhappy marriage. If you don’t like it, you’re expected to leave. (For many people this remains difficult, for financial reasons.)

- No fault divorce, and divorce is no longer considered a major sin.

- For a long time, marriage was a form of transaction. Women and girls were property. Giving your daughter in marriage would merge territories etc.

- Women have more control over their own reproduction. Until the latter part of the 20th century, people married very young because they get pregnant, and that was that.

- People are marrying older. Now in the US, the median marriage age is 28 for men, 26 for women. Before the 1990s, medians were 22-24 for men, 20-22 for women.

- Women were and still are under more pressure than men to be patient and accepting, so resentment is less likely to be explicitly stated.

BUT HAS IT REALLY DIED?

‘Girls vs boys‘ memes frequently depict girls as shallow, vapid, materialistic and boring.

THE IMPOTENT HUSBAND TROPE

When women make jokes about their husbands, it is often an “incompetent husband” trope. For example, “I like my men how I like my tea: weak and milky.”

These are generally expressed in a cute or funny way, so they seem hateful at first glance. But this is simply a more passive aggressive version of “I hate my spouse”.

Such jokes play into the myth that, in order to identify as a man, you must be sexually potent and competent.

DAHL’S DESCRIPTION OF COLONEL BIXBY

Describing Colonel Bixby’s choice of clothing, Mrs Bixby explains via the third person narrator:

The plumage was a bluff. It meant nothing. It reminded her of an ageing peacock strutting on the lawn with only half its feathers left. Or one of those fatuous self-fertilizing flowers — like the dandelion. A dandelion never has to get fertilized for the setting of its seed, and all those brilliant yellow petals are just a waste of time, a boast, a masquerade. What’s the word the biologists use? Subsexual. A dandelion is subsexual. So, for that matter, are the summer broods of water fleas. It sounds a bit like Lewis Carroll, she thought — water fleas and dandelions and dentists.

“Mrs Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat”

WHAT HAS LEWIS CARROLL GOT TO DO WITH THIS?

There has always been much speculation about the sexuality of Lewis Carroll (Charles Dodgson). In common with J.M. Barrie, his sexuality is illegible. This troubles many people, some of whom put any kind of illegible sexuality (or gender) down to p*dophilia.

Both of these historic children’s authors have also been deemed asexual in an era before there was a word to describe lack of sexual attraction. I believe Roald Dahl, too, is scratching around for a word to describe what has always existed in the spectrum of humanity, but which has only had a word since the beginning of the 21st century, after David Jay started the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network (AVEN).

Even so, for much of the early 2000s, it was common even for left-leaning people to think of snails, water fleas and dandelions if someone came out to them as asexual. That’s less common now, but still happens.

WHAT DOES ‘SUBSEXUAL’ MEAN?

Roald Dahl uses the word ‘subsexual’ in this story.

In case you were wondering, ‘subsexual’ has never taken off as a concept, not even in the field of biology. It may refer to a form of reproduction that is not entirely asexual but doesn’t involve the full complexity of sexual reproduction either. In this context, it’s possible that ‘subsexual’ could be used to describe various intermediate or mixed reproductive strategies, but it’s not a common or well-established term. If you look up papers making use of ‘subsexual’ you’ll probably find someone writing about ferns.

What’s clear is this: Roald Dahl does not think much of men who are, by his own standard, less sexual than (sub-) whatever bar is considered acceptable for a man. When he used the word ‘subsexual’, he was referring to human asexuality.

And herein lies the problem with twists in the tale. Too often, a twist reverses the hermeneutical aspect of a story, but not the emotional aspect. Dahl reveals that Colonel Bixby is not ‘subsexual’ (read: asexual) at all. He has purchased his nice new clothes to impress someone, but that someone is not his own wife. Joke’s on Mrs Bixby. Joke is also on any asexual men in the world, becaus nothing is done to reverse the idea, introduced or reinforced by Dahl himself, that:

- Asexuality is a legitimate way of being in the world

- Even if your partner is asexual, that does not give you carte blanche to do whatever you like behind their back. (Communication and boundary-setting is key.)

- Asexual men are no less manly than sexual men, because there is no minimum amount of sex a man must have to get your Man ticket. A man is a man because he identifies that way, same as anyone of any gender.

TRULY SUBVERSIVE STORIES REQUIRE KIND, FORWARD-THINKING AUTHORS

Roald Dahl probably considered himself subversive when he wrote this tale, because in the 1950s women were considered ‘frigid’ by nature. It was the man’s job to ‘bring her round’. (A horribly dangerous way of thinking, we now understand.)

So by creating a wife with her own extramarital sex life, Dahl is saying — refreshingly — that women enjoy sex, too!

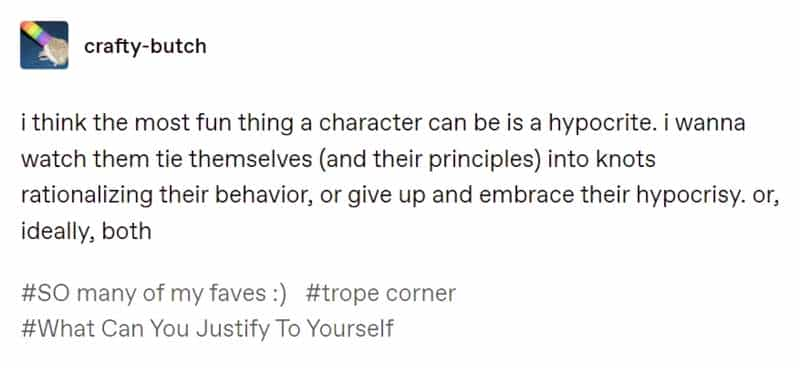

However, it’s way too easy to mess up when writing a subversive narrative, especially one with a big reversal. Roald Dahl has managed a (gender) inversion, but has not subverted a darn thing.

See: Inversion does not equal subversion.

Writers must ask: Who did I throw under the bus for the pre-subverted section of my story? Did I manage to pull everyone back out?

HOW IMPOTENT HUSBAND JOKES ARE ACEPHOBIC

(EVEN THOUGH ASEXUALITY DOES NOT CORRELATE WITH FERTILITY AT ALL)

The aroace (aromantic asexual) community has so few cis men that there are more genderqueer aroaces than there are cis men. No one understands why this is. However, the numbers of cis male aces is likely far higher.

- Asexuality may tend to look a bit different in cis men, in a way not captured by the current asexual community e.g. a typically cis male libido ‘compensates’ for lack of attraction to a specific person in the real world. (We’ve been there done that with the Autism spectrum, which originally excluded girls and women entirely.)

- Cis male aces (who don’t know they’re ace) may identify as cis (rather than genderqueer) partly because male identity is contingent upon having sex with a partner. In other words, an amab ace may feel less attachment to gender and identify as a gender other than male. (Why does this not apply to afab aces? Because having sex is not historically required of cis women before claiming the ‘title’ of ‘woman’, though that is decreasingly the case. For example, it is difficult to be read as a liberated feminist in some progressive subcultures if you’re a woman who is not interested in seeking out partnered sexual pleasure.)

- Cis men may not be drawn to communities in the same numbers, which means they’re less likely to end up on AVEN. Asexual researchers are still disproportionately drawing data from online communities. It’s difficult not to, since the main way aces find each other is online. So it is for researchers seeking subjects.

- Some cis male aroaces may be so very ace that they don’t really think about sex at all, including why they may be experiencing attraction differently. As an example, consider this woman’s story. She was married for 25 years to an asexual man who didn’t know the concept of asexual orientation. He never once wondered what was going on with himself, until it came time for the relationship to end. The wife directed him to AVEN, where he spent 2-3 hours, then came to her and said, with great relief and sadness, “This is me.” But due to a lack of interest in self-exploration (as well as the hermeneutical injustice imposed by the culture at large), he hadn’t worked out his own identity for himself. Self-reflection may be a somewhat feminised activity.

Menippean satire is a subcategory of satire aimed at attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities. Roald Dahl would not have understood that asexuality is a sexual orientation. We now understand that sexual orientation tends to track across a lifetime, and is definitely not something one can change by will or force. So this is not Menippean satire. It’s the bad kind, which attacks a marginalised group (by accident).

Because Dahl no doubt believed he was mocking a mental attitude — an attitude in which wives do not need any sexual attention because women fall into two binary categories: wives and sexual women. (There are other, less generous words to describe each group.) Supposedly, in Dahl’s mind, had Colonel Bixby paid attention to his wife and treated her as a sexual being in the first instance, she wouldn’t have strayed in the first instance. Both, presumably, are punished for their marital failures, which are moral.

ASEXUALS HAVE ALWAYS EXISTED ON THE PAGE

Basically, Roald Dahl’s short story, as well as seething with (very obvious) mid-century misogyny, also evinces acephobia, even in an era before asexuality was a known concept. If anyone is still wondering how this story is an example of asexual bigotry, imagine instead that Mrs Bixby justifies her cheating by conceptualising her husband as gay. She does that by comparing him to some kind of plant, then to an insect. That reads as some kind of hatred, right? Hatred based on his identity, completely separate from the subtextual probability that he is no longer offering his wife sex.

Bigotry aside, let’s take a moment to acknowledge that asexual people have always existed. Writers have always included asexual characters — they just didn’t have the words to describe such individuals. As evinced by Dahl’s description of ‘subsexuality’, anyone with an illegible sexuality (or gender) has always been treated with much suspicion, and epistemic injustice remains the main injustice experienced by aroace communities.

HOW ACEPHOBIA HURTS THE CULTURE AT LARGE

More than that, just as homophobia inevitably affects straight people by enforcing limited gender roles, acephobia also affects everyone, by enforcing compulsory sexuality, and limited acceptable ways of enjoying sex. Basically, no one comes out of this story better off for having read it.

THE PYRAMID OF HATE

“I HATE MY SPOUSE” > “I HATE MY JOB”

So, it’s no longer okay in progressive circles to hate on your romantic (or platonic) partner. In the West, at least, I believe this story is no longer studied in schools (except by way of negative example). At least, I hope that’s the case?

It has been suggested that, in this late-capitalist era, “I hate my spouse” vibes have been replaced by “I hate my job” vibes.

The character of Stevie Budd from Schitts Creek is a nice example of this. She doesn’t actively hate her job — in fact, she kinda likes it because she gets to be alone for a lot of the time and read. (Not at all what running and cleaning a motel complex looks like, but that’s the story.) But she doesn’t love her job. She does it because her job is just her job. She refuses to make it her life’s work, even when she inherits the place. She stands back as a detached observer, making fun of the wacky characters who come through the door, as a comedic spouse-of-yore would make fun of the quirks of their husband or wife.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

As a mental mouthwash, read or revisit “The Gift of the Magi“. In that story, a husband and wife also try to trick each other, and reveal themselves as made from the same cloth, but in contrast to Dahl’s mean-spirited tale, they do this with the most heart-warming of intentions.