“Mr Reginald Peacock’s Day” (1917) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, functioning mainly as a character study.

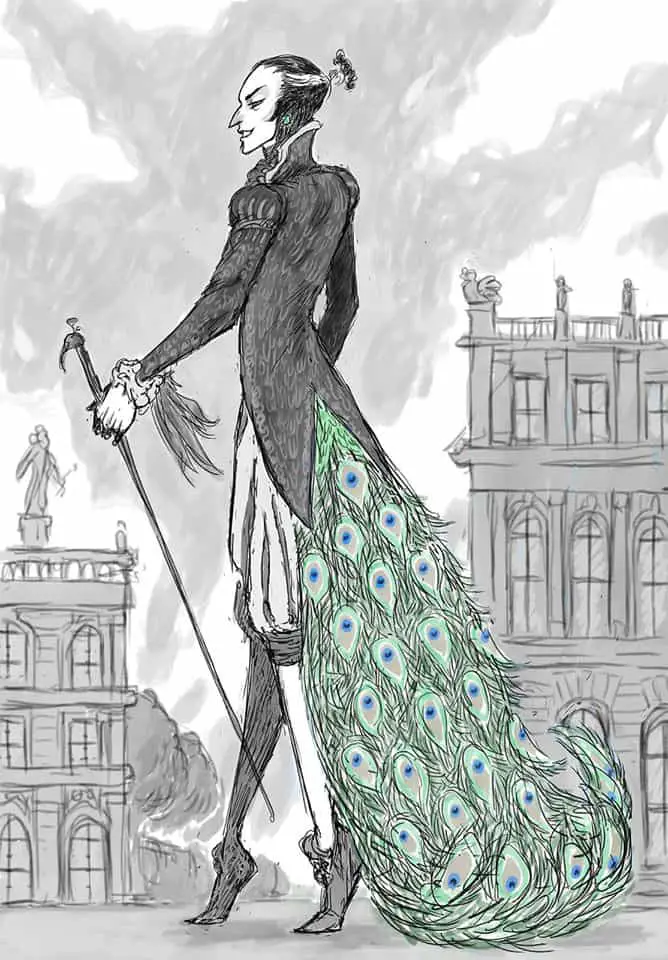

Chris Lilley’s hipster-ironic comedy techniques have been criticised for enforcing stereotypes rather than critiquing them. That said, Mansfield’s Mr Reginald Peacock reminds me very much of Chris Lilley’s high school drama teacher, and I consider Mr G. the modern Australian equivalent of this very old archetype: The youngish white man who considers himself sensitive, unappreciated, entitled and artistic, solipsistically the star of his own show, and wholly unable to empathise with others.

Mansfield’s Reginald Peacock has a clearly symbolic name, and so do other characters in this short story.

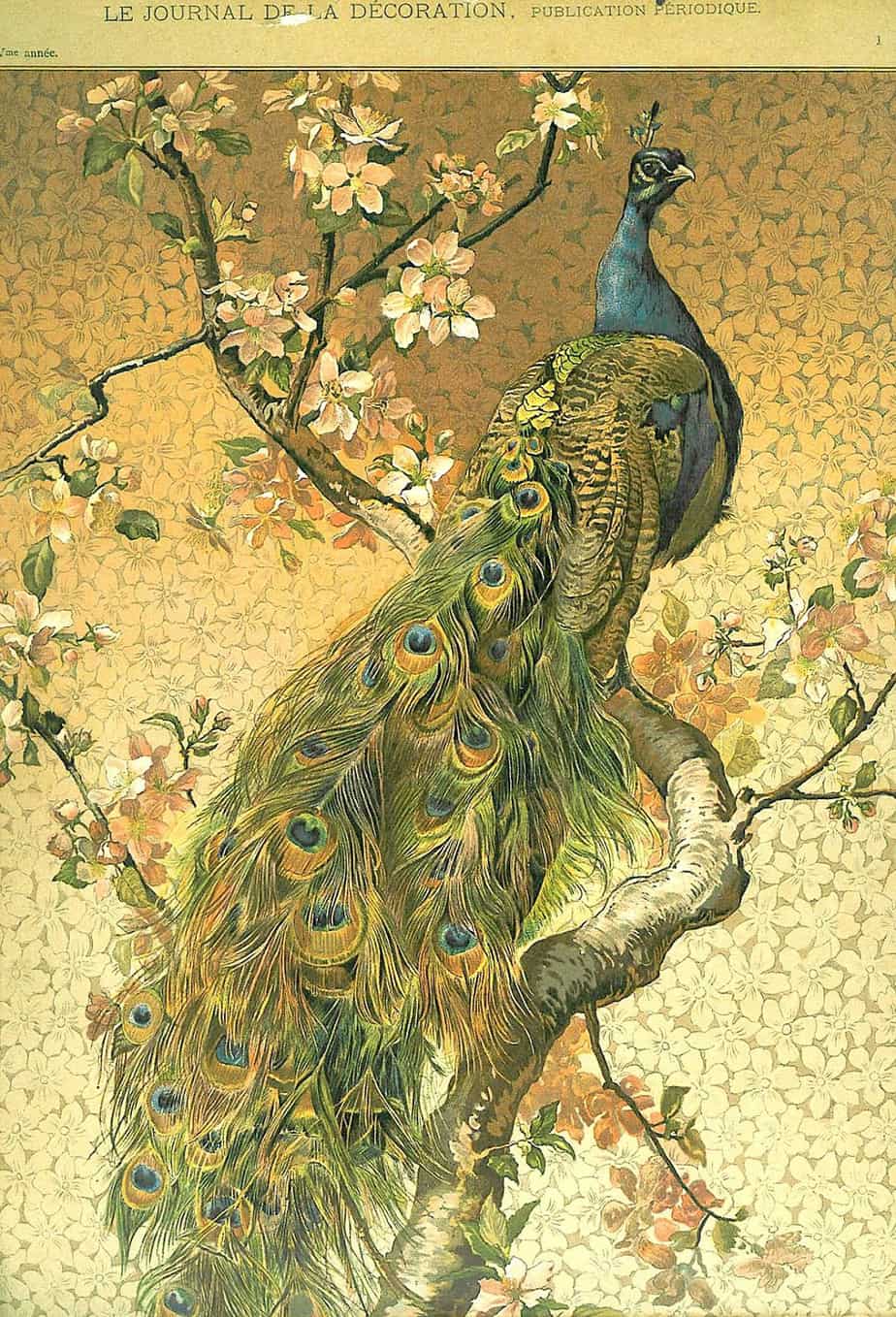

This post will be sprinkled with peacock art, because peacocks were once very fashionable in a way I haven’t seen in my lifetime. Mansfield would have been surrounded by peacocks in fashion and in art. The peacock is still widely understood as a symbol of vanity, which is pretty unfair to peacocks, who are born with their magnificent plumage, and who don’t get to mate unless they strut and rattle their trains.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “MR REGINALD PEACOCK’S DAY”

SHORTCOMING

As a rule of thumb, readers are like ducklings and fall in love with the viewpoint character but I doubt I speak for myself when I say that Reginald Peacock is less empathetic than his wife from the get go, whose point of view we don’t see at all. Reginald is clearly an unreliable narrator. He imagines his wife wakes him up deliberately, but only because the world revolves around Reginald, not because his wife has a full-time ob of her own, and housework really was a fulltime job back in the early 1900s.

Reginald Peacock embodies a number of deadly sins: sloth, vanity, quiet wrath of his own wife. He is clearly envious of the aristocratic acquaintance who asks his children to shake their father’s hand each morning, and comically tries to gain the same respect from his own son by instituting the practice in his own household. He’s basically a comically depicted flaneur. I have a feeling Mansfield was surrounded by flaneurs in her adult lifetime, hanging around with artists and poets. She was also involved in theatre and acting, so I wager she knew a few Reginald Peacocks in real life.

Mansfield has Reginald self-describing himself as a bird, and how his wife clips his wings, which is a bit of an inversion because it’s most commonly women who are described as birds in fiction and art. I almost forgot for a second that peacocks are a bird. Perhaps the peacock is one of the few masculinised birds in fiction, outshadowing the peahens because of their highly decorative plumage. Mansfield didn’t exactly shy away from describing her female characters as birds. I guess Mansfield was equal opportunity on that score. By the way, what do you call the technique of comparing a human to an animal? If it happens the other way round we call it personification, so I’m going for animalification. At one point, Reginald Peacock is also likened to a frog. (He’s doing his daily exercises.) This is interesting because there’s a particular frog-person archetype which is basically the middle-aged equivalent of the younger peacock. (Peacocks are beautiful, like youth; frogs not so much.)

Apart from the seven deadly sins, at first glance Reginald seems prone to coveting, about to breakone of the Christian commandments, first by fantasising about the latest and most beguiling of his female students. The word ‘latest’ is key here, because these women are not fully rounded in Reginald’s mind. So long as they fit his outsourced image of a desirable woman any one of them could easily be exchanged… and oh, they are, as Mansfield demonstrates with one woman after another. Ostensibly this works because Reginald sees a succession of women over the course of his working day. Aenone Fell, Miss Betty Brittle, the Countess Wilkowska, Miss Marian Morrow. The job fits him well: constant novelty all day, and the opportunity to perform in front of a revolving audience. None of these women has the time to get utterly sick of him.

DESIRE

Reginald wants to be the star of his own show, leading a better life than the one he already has. As happens to the best of us, reality punctures his romanticism. For Reginald, it wouldn’t matter who he married, the day-to-day familiarity of his partner would be the killer. Reginald is all about cultivating and seeking out novelty, constantly drawn to mystery.

OPPONENT

The wife remains mindfully unnamed. She goes without a name because she exists as a function to Reginald, not as a human in her own right.

These days, to go without naming a put-upon wife in a story opens the writer up to challenges of sexism. I prefer to trust readers. There’s a darn good reason why Mansfield hasn’t named the wife, but has fully named Reginald , as well as his younger female ‘love’ interests. It’s evidence of his dismissal of her. But this naming avoidance also universalises the wife.

PLAN

In a flashback we learn that the wife has learned to deal with Reginald by immersing herself in the day-to-day running of their household. Reginald earns enough to keep her and their son, and in an era of no social security, this was something.

I think most people have the ability to unsee things if it’s to our detriment. It would be to the wife’s emotional advantage if she were to occasionally play along with Reginald’s games. A number of Mansfield’s short stories end with a female character seeing something (perhaps with the fling of the boot, in this case), then mindfully disregarding it. “Her First Ball” is an excellent example of that. The ‘temporary epiphany’ (more commonly known as ‘phantasmagoric’) is a feature of Impressionist fiction, though contemporary short story writers regularly use it, too. As one example, Helen Simpson utilised the phantasmagoric epiphany in her modern climate change story “In-flight Entertainment“. Climate change is the ultimate ‘look away’ example of our times.

Reginald seems to have some kind of phantasmagoric epiphany in this story though goodness knows what it is. I’m sure it’s only champagne-induced.

We get no insight whatsoever into the psychology of Mrs Reginald Peacock. I am relying heavily on Mansfield’s oeuvre when trying to deduce her motivations.

Reginald himself doesn’t have much of a plan other than to reluctantly be broomed about by his wife, then quietly seeths about her while fantasising about other women. If you can call that a plan.

BIG STRUGGLE

It’s pretty unpleasant being stuck for a (short-story-length) day with this pair, who clearly despise each other. (At least, Reginald despises her.) And we don’t get any big fight scene, either. The scene where Reginald comes home drunk is truncated, or perhaps that’s all that happens before husband and wife drift off to sleep.

ANAGNORISIS

In Christianity the peacock is considered a symbol of rebirth, but there’s no such rebirth here. Mansfield clearly isn’t using that particular aspect of peacock symbolism. Reginald starts out lazy, self-absorbed and vain, and ends the same way.

It’s possible that his wife finally had a gutsful of the guy and experienced a self-revelation of her own.

But we don’t get to hear her response. (And I don’t imagine that’s how it went down. See below.)

NEW SITUATION

However, there’s one small shift that happens at the end, and that wholly resides within me (and I assume in other readers). I see what Reginald’s wife must have initially seen in him, and how she might put up with him still. To be clear, it’s not evident that she does put up with him. This was an era in which a married woman with a child was economically and socially unable to leave her husband. But when Reginald draws her into his own game for a moment, even after scaring her with the clunk of his flung boot, he says, “Dear lady, I should be so charmed–so charmed!” and I’m reminded of the ending of another Mansfield short story, “A Blaze“. At the end of “A Blaze”, husband and wife (Elsa and Victor) come together in what I consider an amae relationship, in which one person loves to be ‘babied’ by the other. Both get a lot of reward from it. (The Japanese concept has far more to it than that.)

If “A Blaze” had been published after “Mr Reginald Peacock’s Day” I’d have guessed that the marriage dynamic in “Mr Reginald Peacock’s Day” were a practice story for the more sophisticated but similar relationships in “A Blaze”. In fact, “A Blaze” is the earlier story.

EXTRAPOLATION

The title “Mr Reginald Peacock’s Day” suggests this is a typical day-in-the-life-of story, not an extraordinary one.

Wouldn’t you like to know how (if) Reginald’s wife responded? I want her to throw his other boot at his head, but I doubt that happened. I suspect this is one of those relationships where it’s fight fight all day, kiss kiss at night.

But I don’t know. My prior reading experience of “A Blaze” is colouring my interpretation of Mr Reginald Peacock’s marriage. Sticking only to this particular story, my best evidence for a peaceful reunion is the darkness. Reginald is clearly a night person, preferring to sleep into the day and partying at night. When he returns home to his wife, he can’t see her through the darkness. Aided by liquor and by the fantasy life he’s been living all evening without her, the darkness itself might provide sufficient mystery for him to pretend his wife is not his wife, but a more mysterious and alluring member of his cast. In turn, she might imagine Reginald is not Reginald.

RESONANCE

Even today, highlighted by the 2020 pandemic, the work traditionally expected of women has less social and economic value attached to it than work traditionally done by men. Today, much of women’s work is also invisibilised. I’ve wondered at times if the housewives of the early 20th century at least had their work considered proper work, even though they weren’t personally recompensed, of course.

Mansfield’s 1917 creation of Mr Reginald Peacock is the painfully comic portrait of a man who sort of does consider the running of a house ‘work’ but sort of actually doesn’t at all. We know this because he encourages his wife to hire someone (while also making it impossible for her to keep anyone). The hiring of help is more about status for himself rather than help for his wife. Reginald’s his cognitive dissonance is right there on the page, because when his wife requires him to get out of bed by late morning, and to let her know if he won’t be in for his evening meal, he clearly disrespects the job she is doing.

This short story shows that in the first half twentieth century, while housework and childcare were indeed considered a fulltime job, the cognitive dissonance of husbands infuriated women, even temporarily married and child free women like Katherine Mansfield: Wifely work was proper work — invaluable! — but not valued.

FURTHER READING

Is amae that unique to Japan? The short answer is no. But how and why did it become viewed as a Japanese-only concept?

The Anatomy of Stereotypes: Japan and the “Amae” Myth

Header illustration: ‘Le Soir’, a decorative panel by Camille Martin (1861-1898)