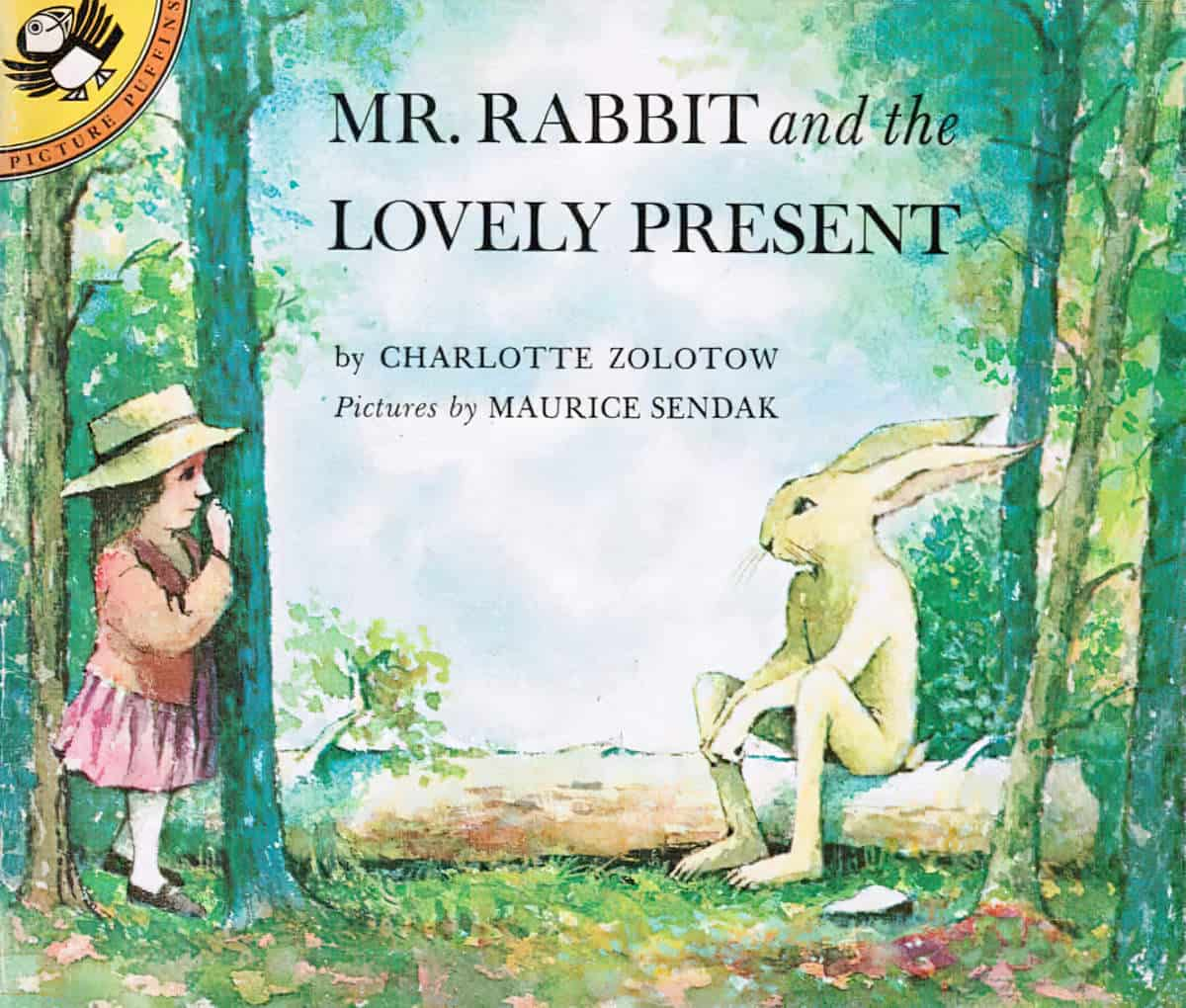

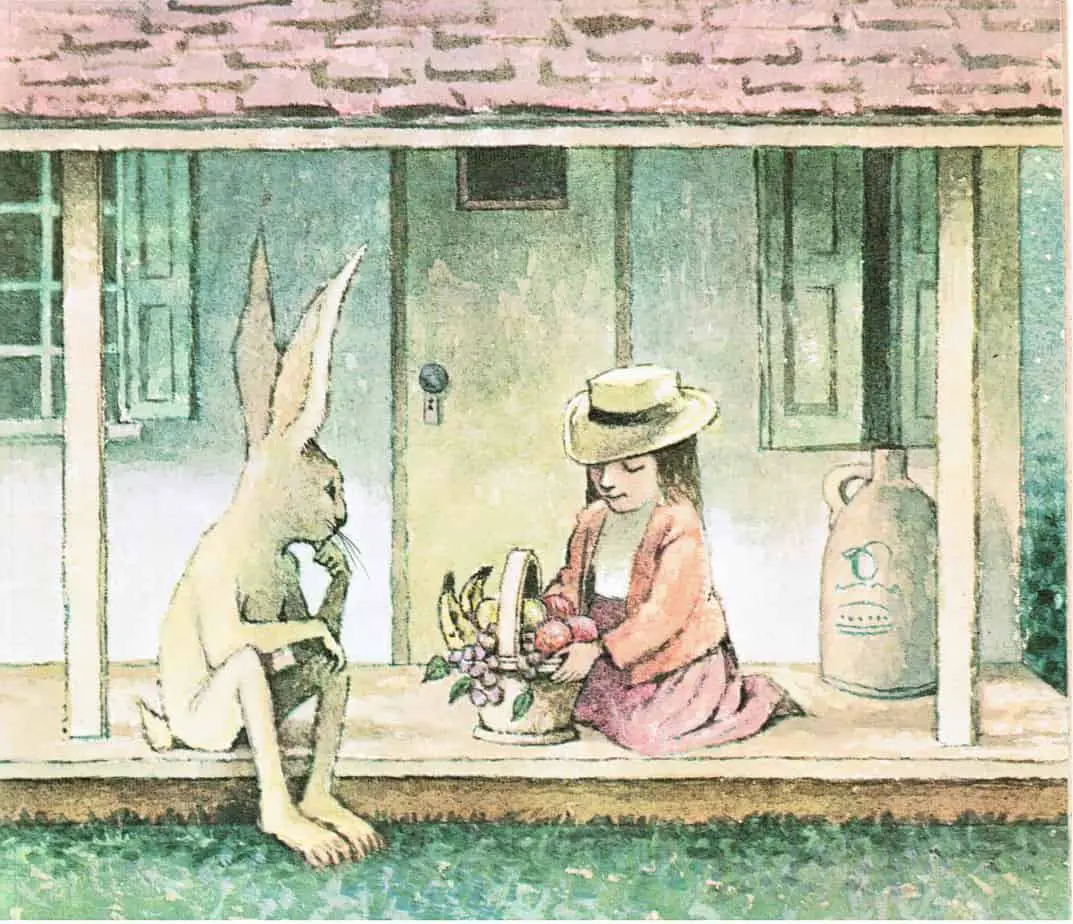

Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present is a 1962 picture book written by Charlotte Zolotow and illustrated by Maurice Sendak. Zolotow and Sendak were both giants of American picture book world. Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present was also a Caldecott Medal Honor Book, so it’s interesting to look through a contemporary lens and see how picture books have changed, or how reader responses have changed. The word which frequently crops up in consumer reviews of Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present is ‘creepy’.

It’s wonderful, and probably necessary, for children to have the opportunity to do something nice for the adults in their lives. Children by their nature must constantly be on the receiving end of care, attention and gifts, but it’s a wonderful feeling to be a child and to do something you know is truly appreciated by those who normally take care of you.

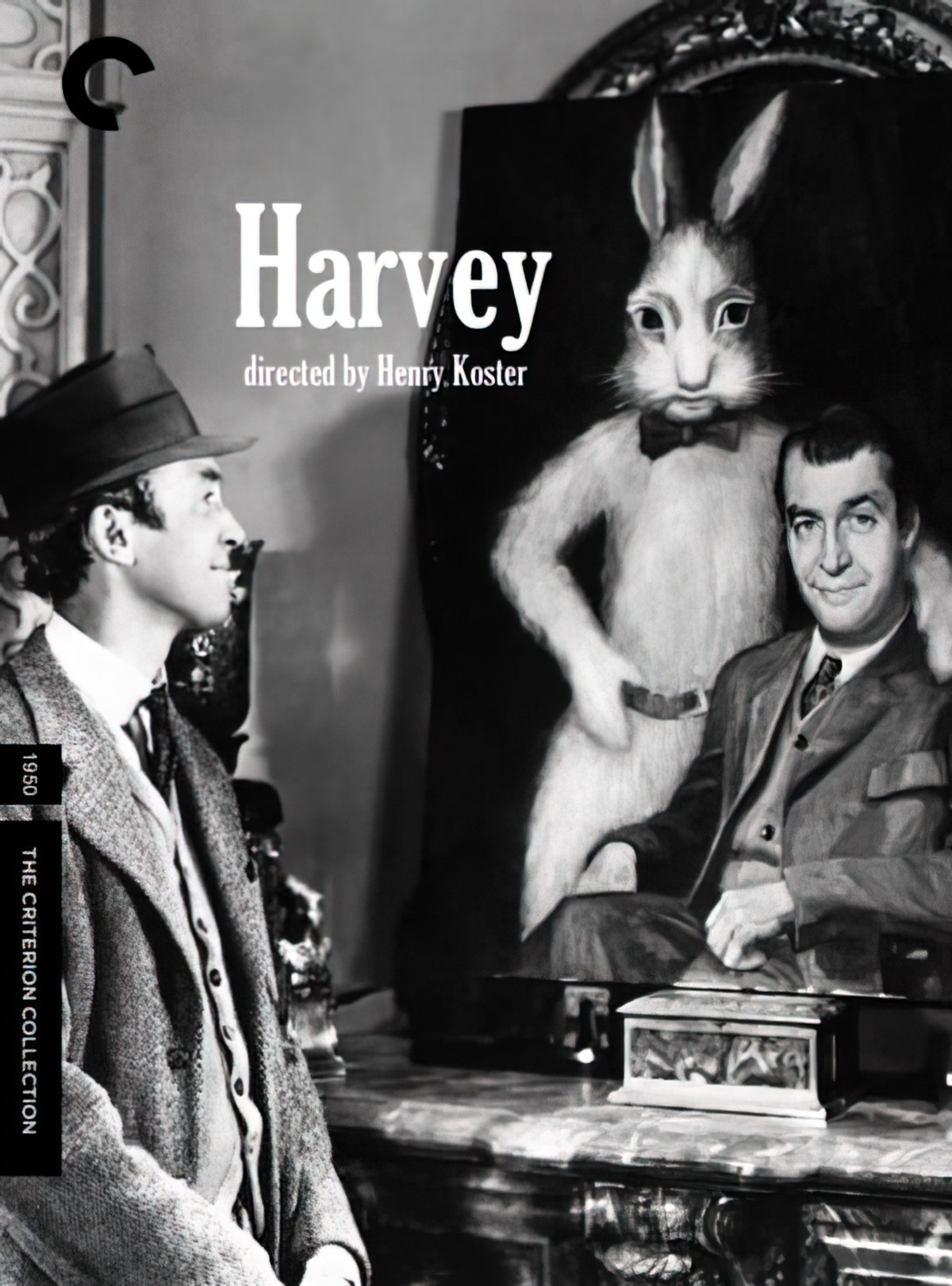

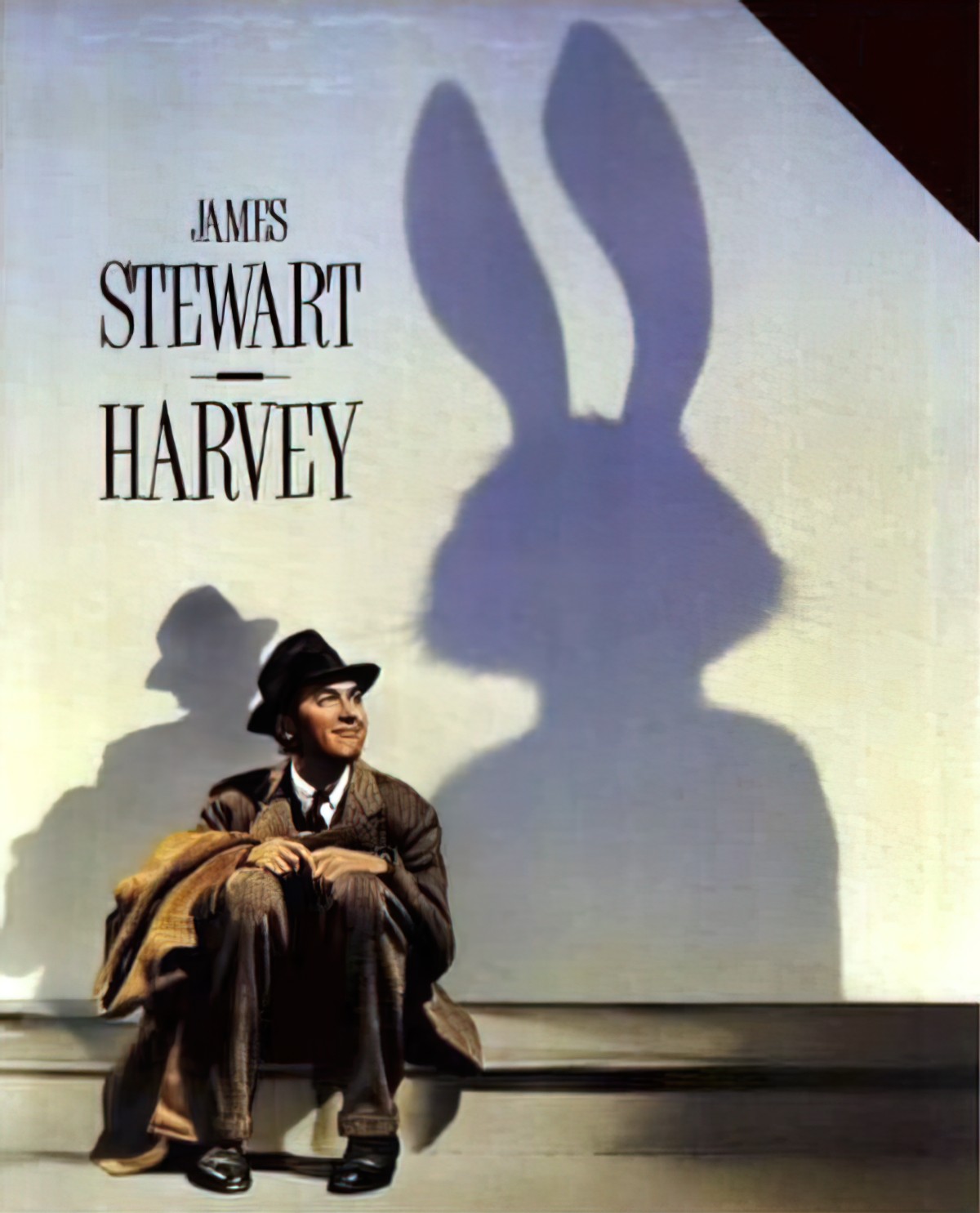

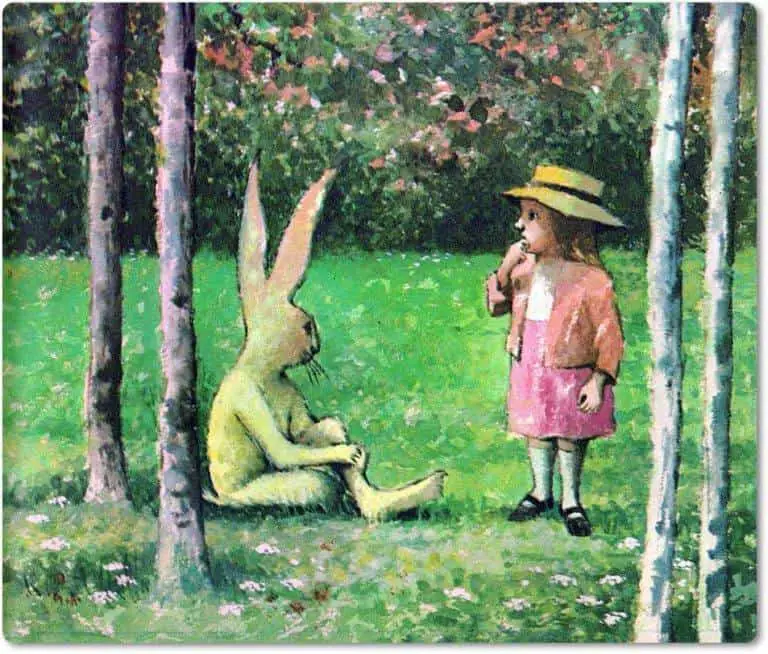

Mr Rabbit seems to be more of a Pooka, as in the classic movie Harvey of the mid 20th century.

Harvey is a 1950 American comedy-drama film based on Mary Chase’s 1944 play…The story centers on a man whose best friend is a pooka named Harvey, a 6 foot 3.5 inch tall invisible rabbit, and the ensuing debacle when the man’s sister tries to have him committed to a sanatorium.

Wikipedia

I’m Gen X, so for me the massive rabbit friend in Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present reminds me of Donnie Darko.

The púca (Irish for spirit/ghost; plural púcaí), pooka, phouka is primarily a creature of Celtic folklore. Considered to be bringers both of good and bad fortune, they could help or hinder rural and marine communities. Púcaí can have dark or white fur or hair. The creatures were said to be shape-changers, which could take the appearance of horses, goats, cats, dogs, and hares. They may also take a human form, which includes various animal features, such as ears or a tail.

WIKIPEDIA

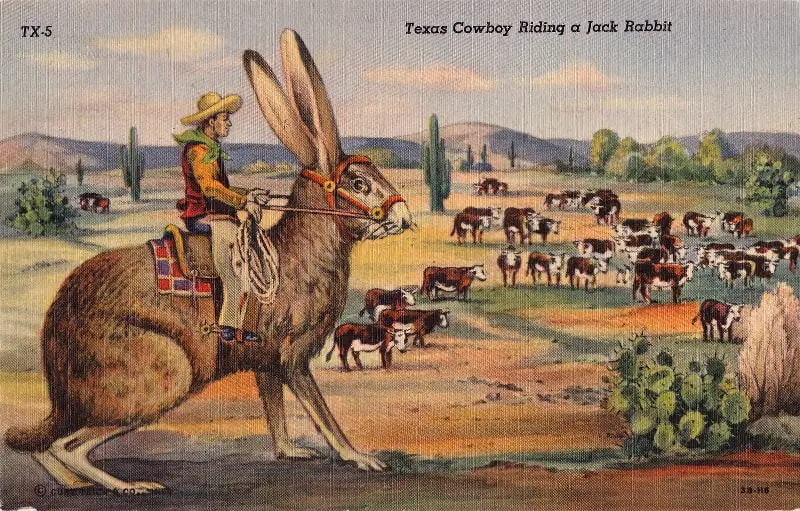

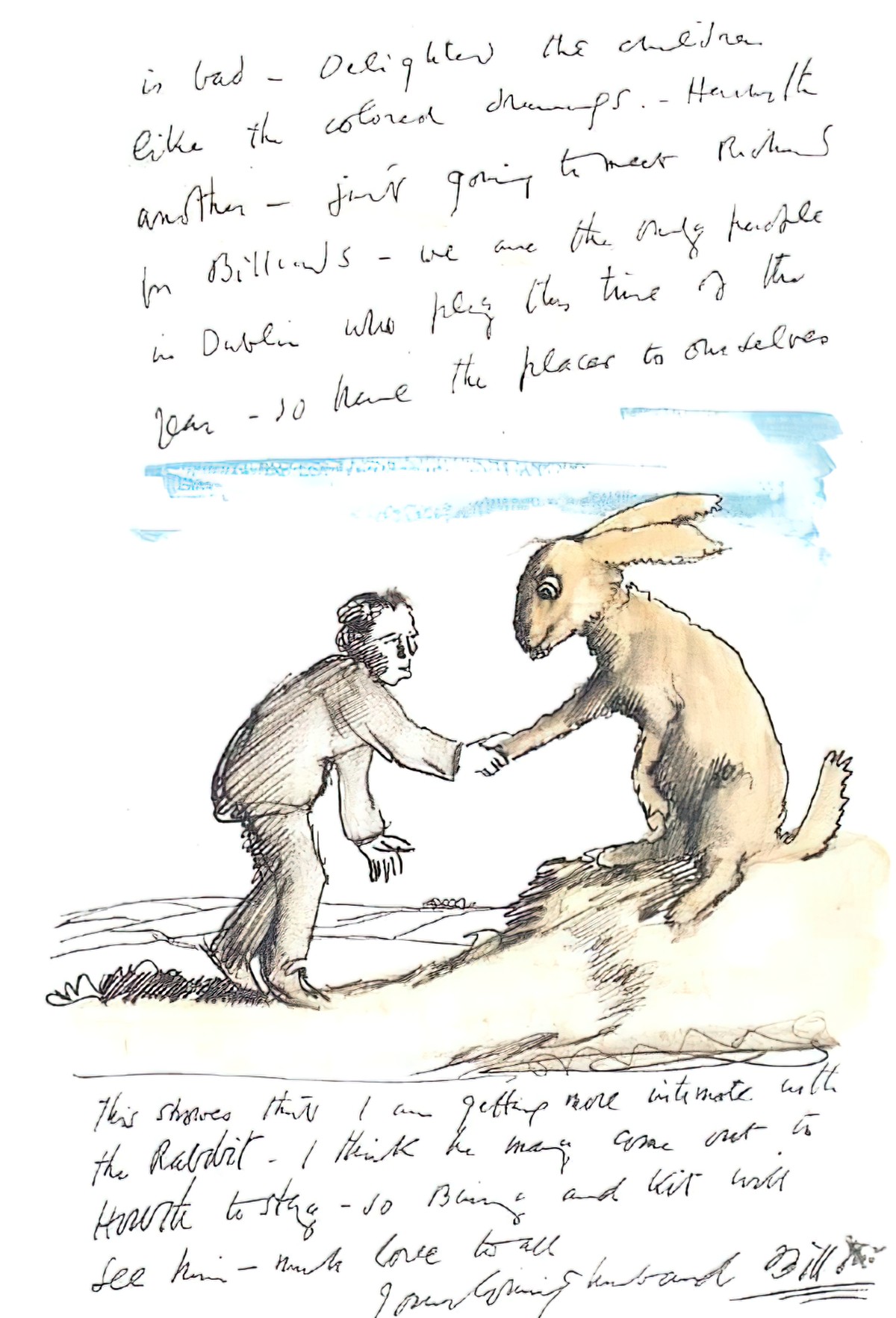

There was a time when massive rabbits were in fashion. The example below is an ‘Illustrated letter to Grace Orpen’ by William Orpen, undated. Fantasy rabbits have gotten a lot smaller in children’s stories, perhaps because massive rabbits are CREEPY.

SETTING OF MR RABBIT AND THE LOVELY PRESENT

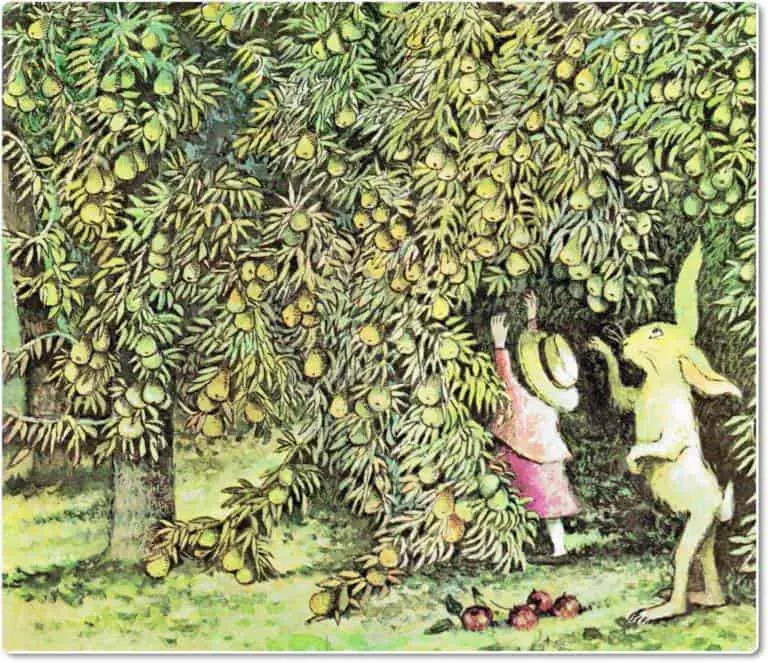

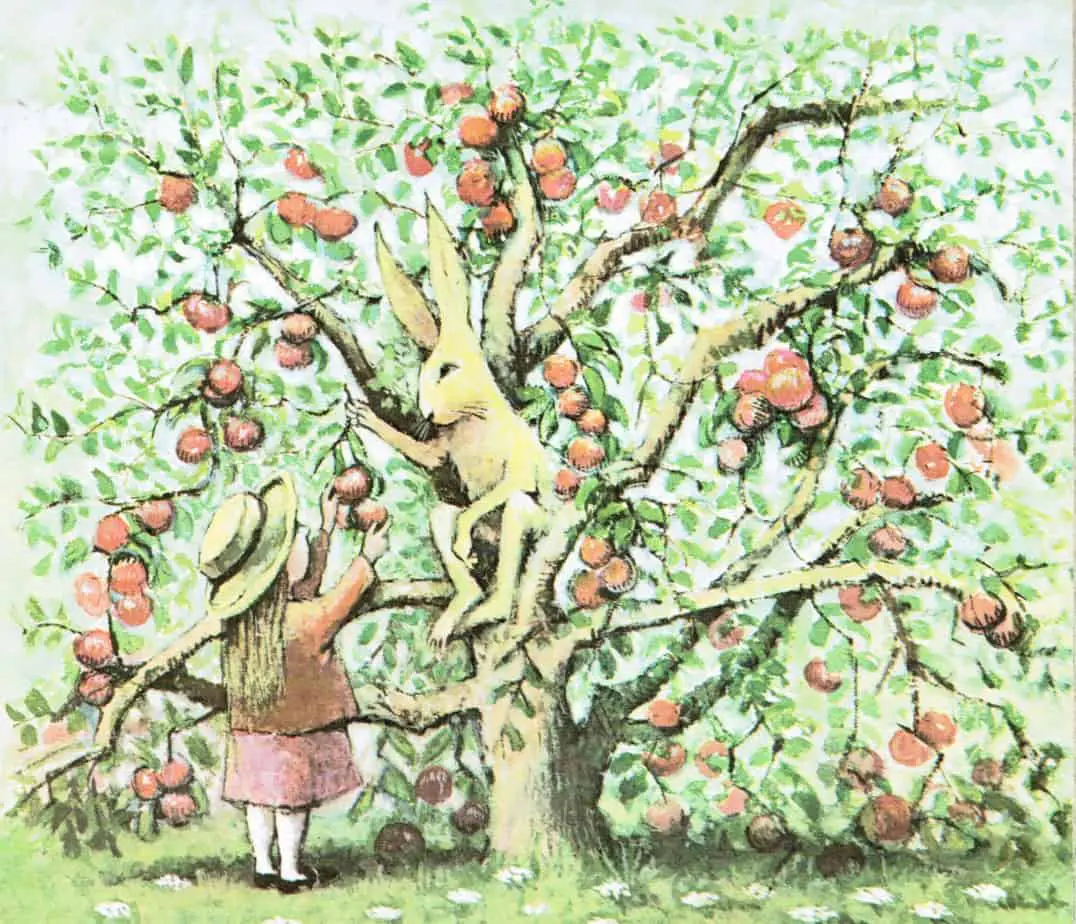

This is a fairytale setting in a prelapsarian forest, where there is always enough food.

Noteworthy: the absence of blue. Like Rosie’s Walk, there is a complete absence of blue in the palette, a decision clearly made by Maurice Sendak, who had plenty of opportunity to include some blue when the text talked about ‘blue’ grapes. He made them purple (close enough). Interestingly, blue as a concept is relatively recent. See for example reference to the ‘wine dark sea’ in Homer’s Odyssey. Sendak has ignored the concept of blue and gone in the reverse direction. Blue does not exist. Even the sky is greenish.

Why might an illustrator avoid blue? Blue tends to feel ominous. Even the warm tones can feel a bit scary.

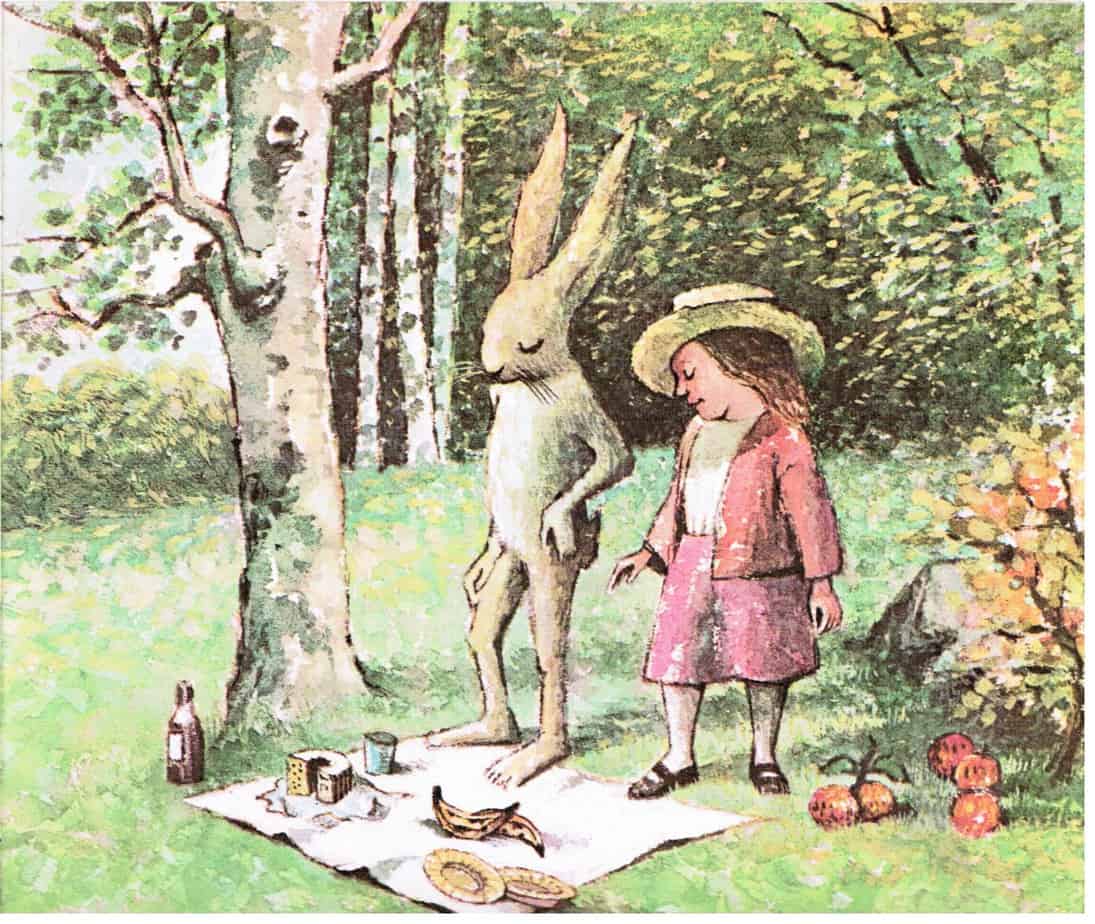

The forest is a European forest, which explains why The Little Girl and Mr Rabbit don’t find a banana tree, but instead stumble across someone’s abandoned picnic. I’m not sure if it’s a common reading experience to wonder who abandoned their picnic like that, and whether they’re about to come back to find their banana missing, but that’s where my mind went.

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF MR RABBIT AND THE LOVELY PRESENT

Not all carnivalesque stories are paced like The Cat In The Hat, or like one of Madeline’s adventures. Sometimes fun doesn’t look like a carnival, complete with the flying trapeze. Sometimes it looks very much like this: A retreat into imagination, where the pay off is simply doing something nice for someone you love.

The pace of the book is entrancing, part suspenseful, part predictable, feels like sailing in a light summer breeze. I can see why children have loved this book for half a century.

CONSUMER REVIEW

PARATEXT

One of the older covers of this book depicts the girl smiling at the ‘camera’.

[L]ike the smiling image of the girl on the title page of Mr. Rabbit, pictures often imply through signifying gestures that the victims of our gaze are willing victims. We all know that we should “smile for the camera”—show a facial gesture that signifies pleasure to those who will eventually see the picture, and who will view it with a relentless attention that would cause us to stop smiling and feel abused if we experienced it in reality. The covers of many picture books ape such photographs and show their main character in a sort of introductory portrait that implies an acquiescence in the right of viewers to observe and to enjoy what they see. There are also, of course, many picture books whose covers show their protagonists simply getting on with the business at hand, whatever that business may be. But interestingly, those who smile and invite the gaze of viewers are most often female, the others usually male.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

An Every Child is at Home

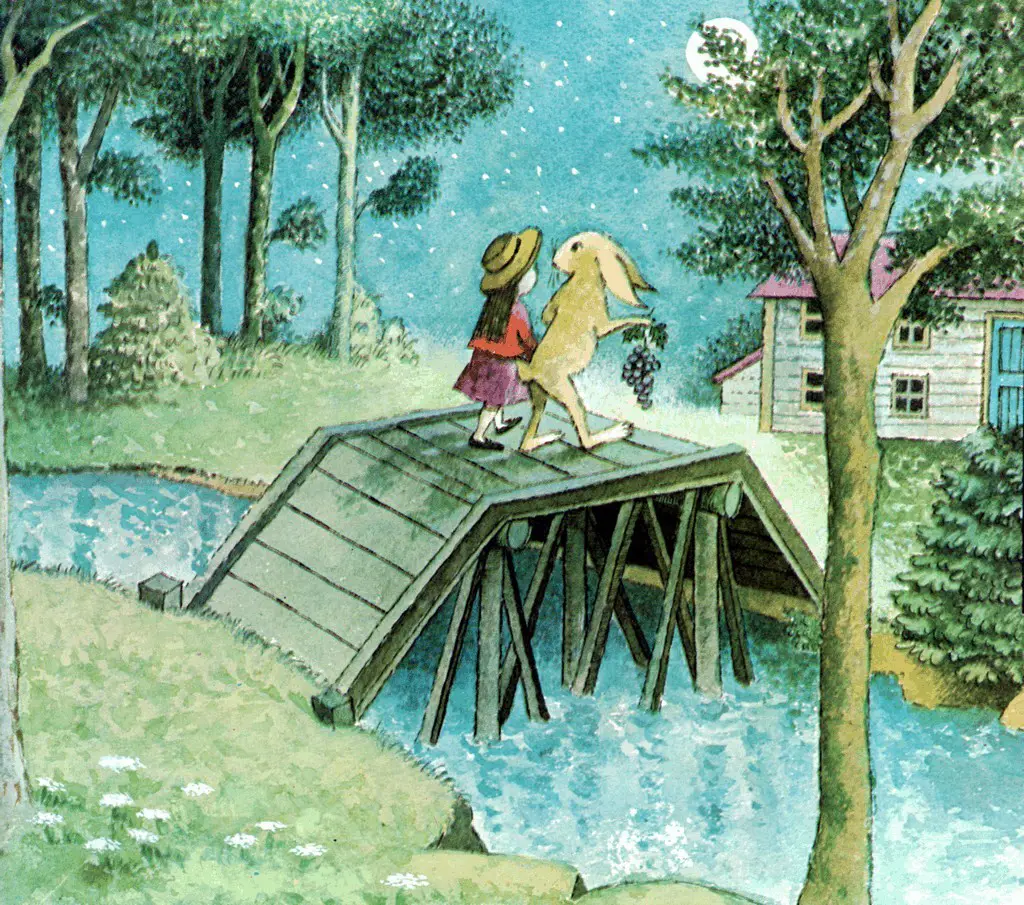

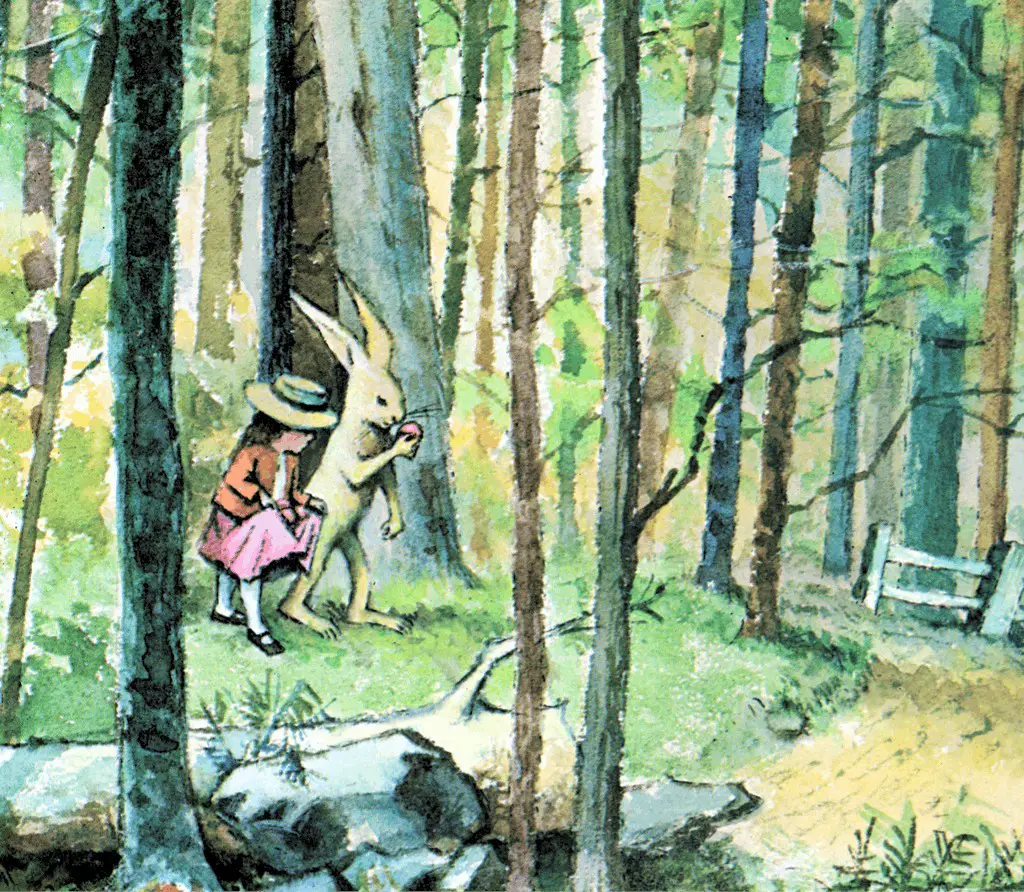

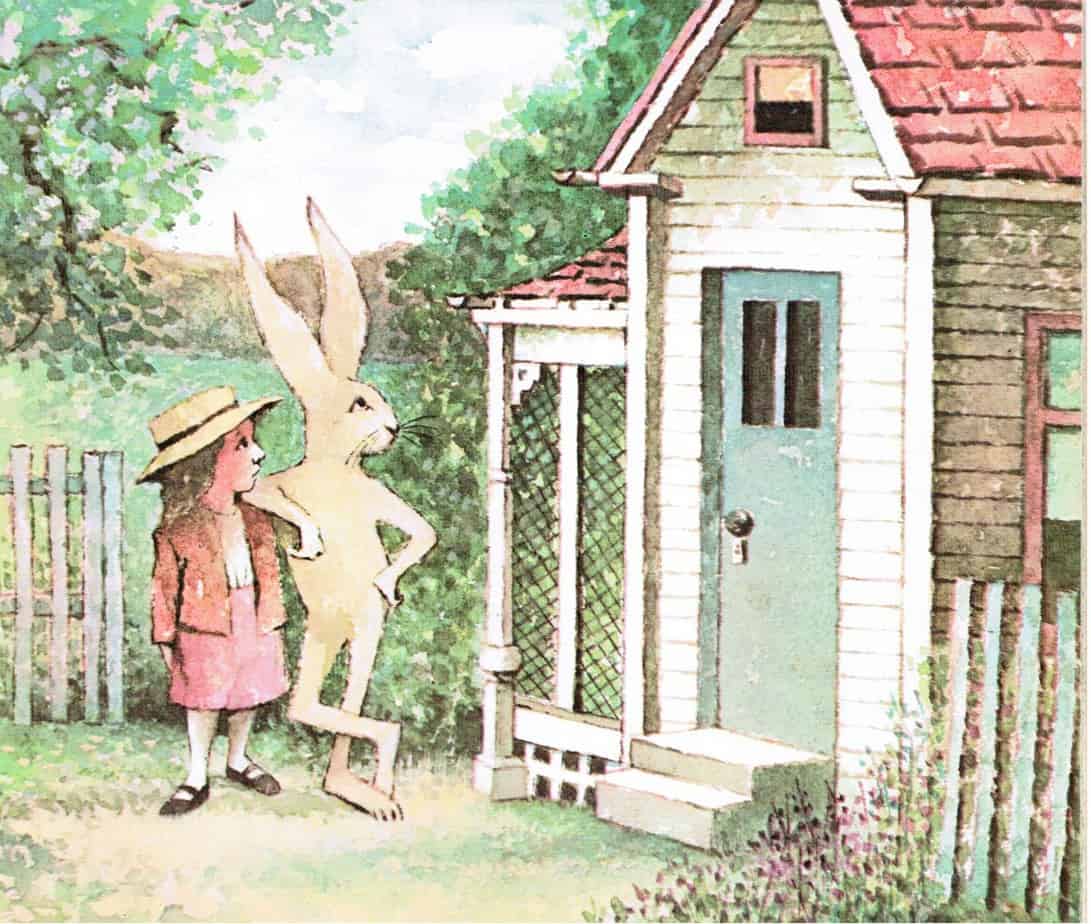

The Little Girl and Mr Rabbit start their story on a hill in the forest, but the the buildings of civilisation (home) are visible nearby.

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

The Little Girl wants to find the perfect gift for her mother. This is her idea of fun, and regardless of whether this character is a boy or girl, this is what gives the story a feminine sensibility. The female maturity formula is at work here, and so is our patriarchal culture in which girls are more likely to be encouraged to think about the needs of others than boys are. (This, after all, is at the heart of patriarchy.)

We still need more stories in which masculo-coded characters are the stars of stories like these.

Disappearance or backgrounding of the home authority figure

Adults in this story are physically absent but emotionally very present. The Little Girl spends the whole time apart from her mother thinking about her mother.

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

In this story, the rabbit is there from the start.

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

Unusually for a carnivalesque story, Mr Rabbit has the authority. We can even see it in the names: little girl versus Mr. The rabbit is the authority when it comes to saying things like “You can’t give red”. Usually, carnivalesque rabbits who turn up out of the blue are a bit more fun than this guy.

Modern audiences tend to read this rabbit as creepy. Some readers find him less creepy when they code him as imaginary. For others it doesn’t help. Here’s a man-sized rabbit suggesting red underwear, leaning on a little girl, hanging out with her in the woods… Not questions that were significant (or raised) in the 1960s when this book was nominated for a Caldecott.

Fun builds!

Rather than ‘building’, this carnivalesque story utilises a repeating structure. Red, yellow, green… The story functions pedagogically, teaching the difference between concrete and abstract nouns (obliquely), colours (for younger readers) and also to consider whether the recipient of a gift would like it. This is complex for young readers, who are inclined to give gifts they themselves would like. The little girl is practising theory of mind.

Although this story is repeating, there is still a build. There always is. Sometimes the build is subtle. The build here is in the amazingness of the gift. By the time they look up at the stars and consider giving the stars, the story is utilising a version of The Overview Effect. Many stories feature a contemplation of sky at this part of the narrative. This helps readers to connect the events of any given story to more universal themes. (Yes, it’s very literal.) And because we’re used to stories structured in this way, a glance up at the sky (or down from the sky in a low angle shot) helps to convey the sense of an ending.

Peak Fun!

Surprise! (for the reader)

On first read, I half expected the story to end with the appearance of the mother, and her pleasure at receiving the thoughtful gift. But the mother never appears. We are left to imagine how much the mother will appreciate the fruit basket.

The gag in this story is very minor:

“Happy birthday and happy basket of fruit to your mother.”

(Because it’s not usual to say ‘happy basket of fruit’ but I’m sad it never took off.)

Return to the Home state

The rabbit and girl have said goodbye. This particular carnivalesque story did not begin inside the house, so it does not end inside the house, either. ♦