Moving Molly may sound like a drug dealer’s handbook but is also a children’s picture book written and illustrated by Shirley Hughes (1981). Shirley Hughes is one of the big name picture book storytellers from my childhood. Another favourite is Dogger. I’ve also analysed Up and Up on this blog.

I know that Shirley Hughes’s illustrations are not for everybody. She has a highly recognisable style, but I haven’t seen much similar in modern picture books, possibly because digital illustration has changed the way illustrators work, and also probably because fashions have changed. When I describe Hughes’s style as ‘grimy’, I do mean it in the best possible way. Her colours are darker than you might expect for a picture book, the hues are almost a bit muddy, and the cross hatching adds life and texture, avoiding the illusion of utopia. The children and adults are not ‘pretty’. The illustration style matches her stories perfectly, because Hughes never gives the message that life is easy and perfect; her stories are set in the real world of children, full of appropriately child-sized struggle.

SETTING OF MOVING MOLLY

- PERIOD — contemporary (late 70s, early 80s)

- DURATION — some months

- LOCATION — from the city to the country (perhaps from London to Sussex?). I’m thinking of that British comedy The Good Life, in which a young couple move to a lifestyle block out of the city with thoughts of living off the land, but they don’t know what they’re doing. I find the show annoying because Felicity Kendal is required to play a laughing, smiling obliging wife to a very annoying husband. (The actress has commented on this since.)

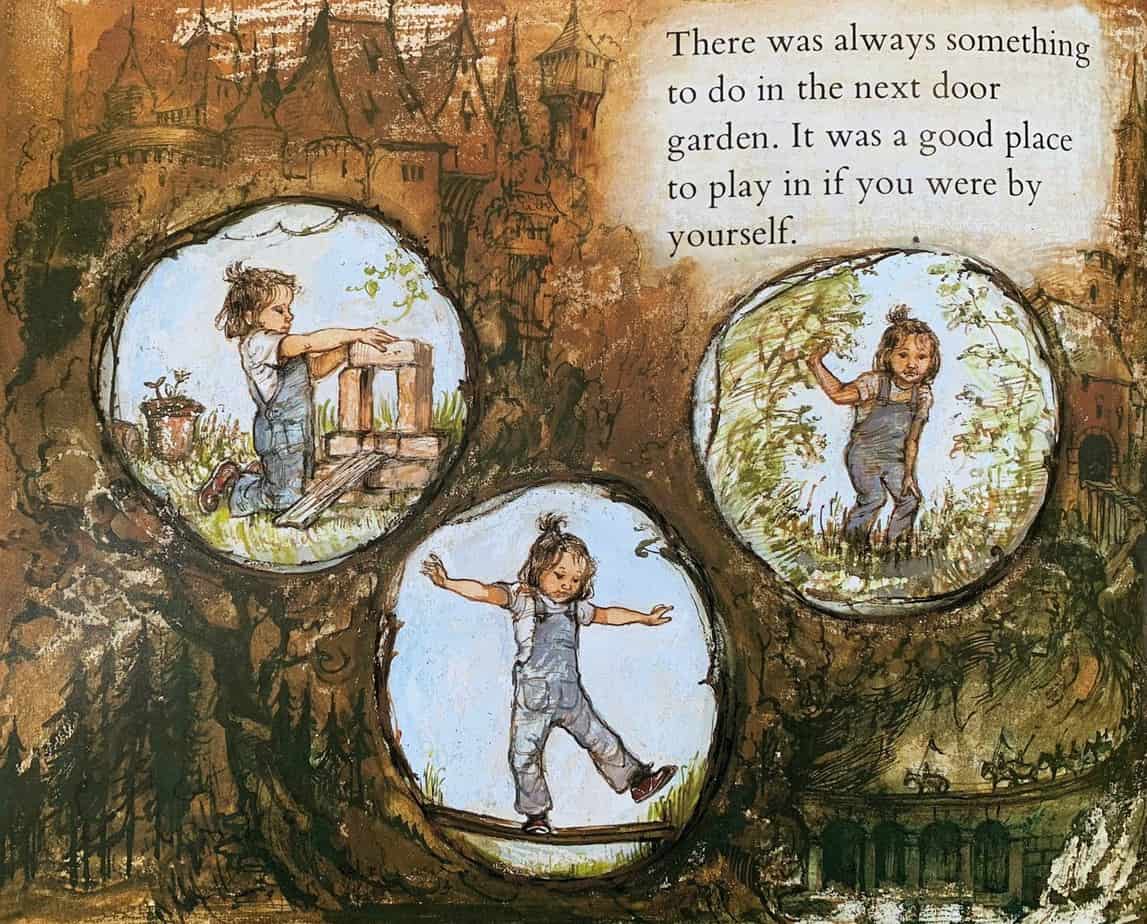

- ARENA — The country garden opens out into an imaginative storybook jungle, and the hole in the fence functions as a fantasy portal. The imaginative part of the world is on-the-page imaginative, so functions like Bridge to Terabithia. Shirley Hughes’s spot illustrations of Molly playing by herself are backgrounded with ghostly, slightly muddied sketches of how she transforms her play inside her head. You might not even notice at first glance.

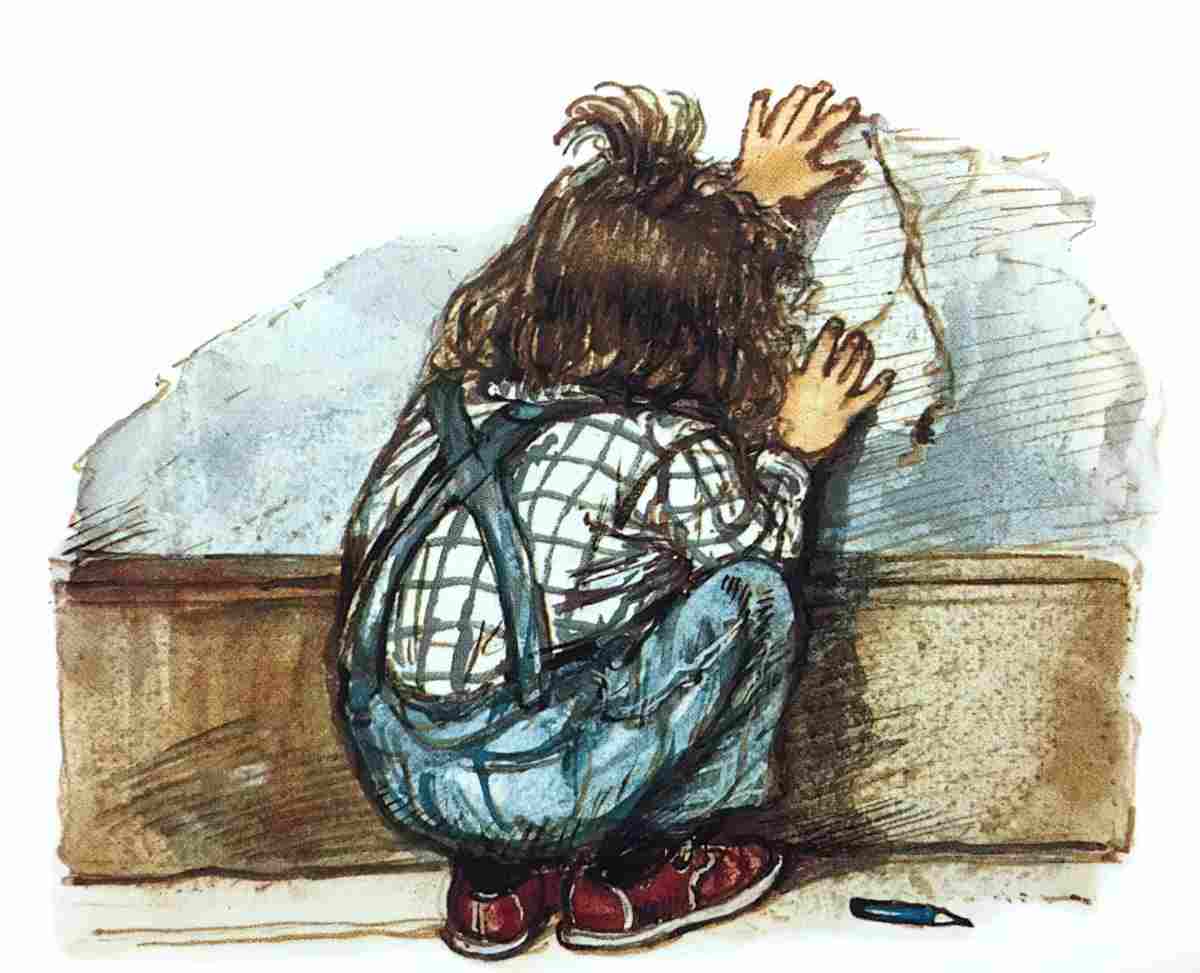

- MANMADE SPACES — The city juxtaposes with the country. Many children’s stories elevate the natural setting as the ‘correct’ place to bring up children, but Shirley Hughes, who wrote for working class British children, avoids this. How awful must it be for city living kids to constantly receive the message that real adventure only happens in the country, and only if you’re sufficiently privileged to have a garden? Notice how Molly is perfectly happy to see the legs and the cats of passersby at their city house, even though the mother is not happy to be living partially underground? Hughes understands that for children especially, home is where the family is. When Molly finds the bit of loose wallpaper, the reader sees that this is a grimy sort of place, but it was Molly’s first home. She says goodbye to her home in a typically childlike way, and we empathise when she writes her initial in crayon then sticks the flap down with spit. Hughes’s illustrations of home are never of tidy, Pinterest-white middle class houses, but messy, overflowing, lived-in looking houses. The flap of wallpaper, ordinarily hidden by the bed, symbolises this ‘not perfect but still very loving home’.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Shirley Hughes winks at the adult reader by subtly conveying a picture of parents who aspire an Escape To The Country lifestyle but who find themselves just as busy with the ordinary pressures of childrearing once they get there. This culminates in the final line, in which the father next door is too busy to do the garden. Whereas he may feel a little bad about that, for kids (and the cats) this is marvellous. They get to keep the ‘wilderness’ for themselves.

- WEATHER — The weather throughout the story is good for playing outdoors. It looks like a British summer. Chilly but pleasant if you’re moving about and rugged up.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Something precious to Molly is the go-cart which has been made out of her old pram. This repurposed baby gear is a reminder to Molly that she is growing up, and she will continue to grow, and things will continue to change. She is saying goodbye to her house, but like a typical child of her age, she doesn’t look back for long. I am about Molly’s age and moved house at about Molly’s age. I remember kissing the front door of our house goodbye. My father said to my mother, “I think she’s sentimental.” I was still so young that they were learing my personality. It’s completely believable to me that Molly would say goodbye to her house in the way that Shirley Hughes writes her.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — In the wider world of the story, working class parents aspire to the luxuries enjoyed by the middle class. This is very much a story of its time. From what I understand, it’s almost pie-in-the-sky for English parents of a young family to save enough to buy a property in the countryside even if they do scrimp and save by living in cheap housing for a while.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The difference between Molly and her mother is palpable. Although Molly’s mother is barely on the page, it’s clear that she is dissatisfied with bringing her children up in a small underground apartment. In storytelling, it is often the mother/woman who is dissatisfied with the living situation and drives for better. Oftentimes this is presented as unreasonable pressure on the husband/man. But Shirley Hughes doesn’t judge. I’d like to extend some sympathy for this woman, who has rather a lot of small kids in a very small dwelling. Let’s not underestimate the intensity of parenting, even with plenty of space. I’m happy for Molly’s mother that the family has been able to move to the country. My take on the situation: The mother may have been unhappy living underground, seeing nothing but legs and cats, but Molly was happy wherever her family was.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MOVING MOLLY

Publishers and agents are constantly telling querying writers to read current picture books to get a sense of what’s selling right now. From what I can gather, Moving Molly has the sort of plot which has been pushed up into chapter books and junior fiction; a child moves house, feels loneliness, copes psychologically by using her imagination, and finally finds new playmates. For better or worse, modern picture books are about 200-400 words. Moving Molly is a rare example of a ‘moving houses’ book about a preschooler, and that’s why I think it remains so important. It’s rare.

PARATEXT

Molly wished that they had a real garden, big enough to play in. Then one day, her wish came true! Mum and Dad told the children that they had found a house with a garden for them all to live in! Right away everyone began to make plans.

marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

Molly is in this lonely inbetween space, between being a baby and being a big schoolgirl with her own friends. Many children’s books begin with the main character in a place of loneliness, and almost every single moving house book starts with loneliness.

DESIRE

We are told that Molly wishes she had a big garden to play in, starting with the marketing copy. But I’m digging my heels in a bit here. I think Molly was pretty happy where she was. The desire to move has been instigated by the mother or parents.

The deeper desire, shared across pretty much all children’s literature: to have fun and find acceptance with friends. (There’s no need to make the deeper desire original in a story — there are only a few big needs to choose from, and the need for social connection is a big one.)

OPPONENT

Storytellers are told that some kind of opposition is necessary for a complete story, and that the opposition will be personified if it’s to sustain audience interest. So what to make of a story like this one? Molly is ostensibly getting exactly what she wants. She enjoys the cats, watering pot plants with her mother, and now they’re about to make a big exciting move to the country.

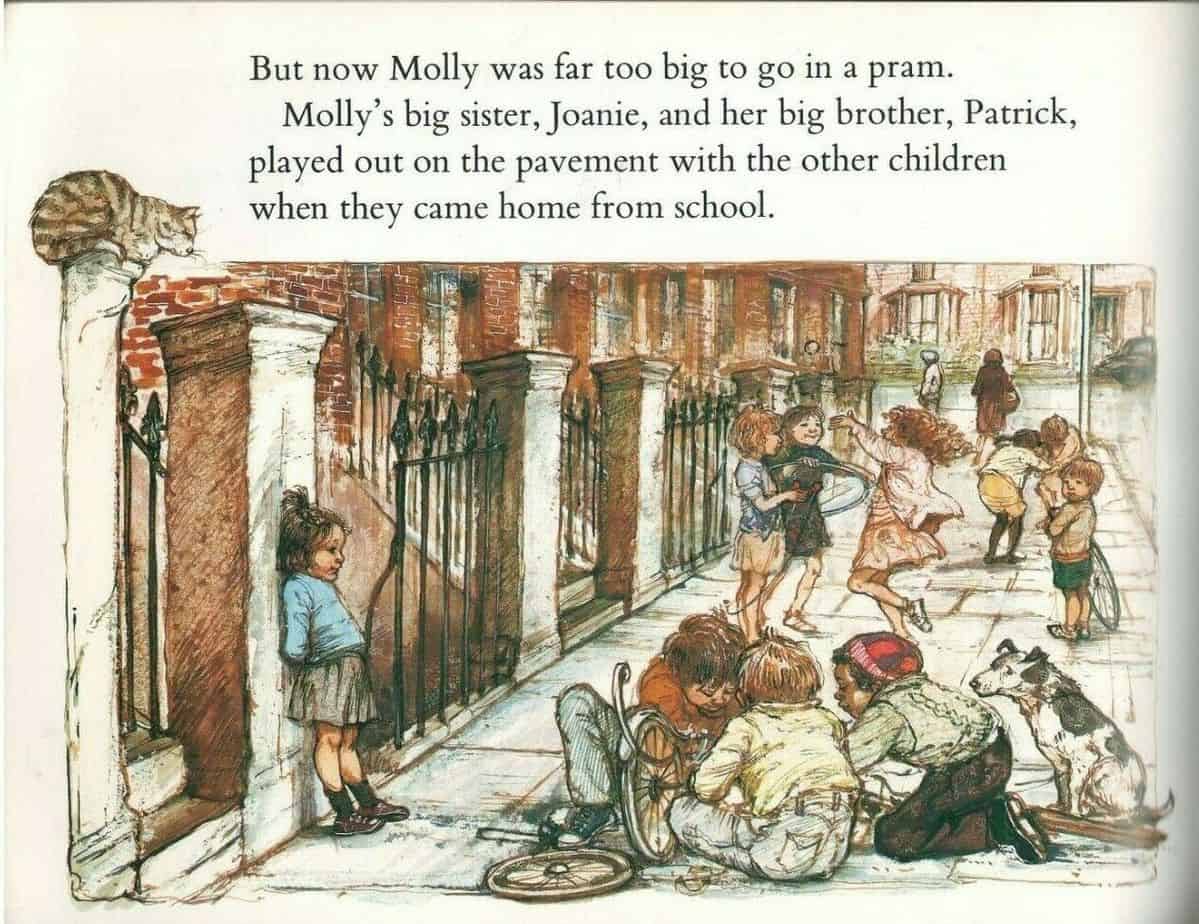

Look closely at the pictures and the conflict is there. Molly is a middle child, not young enough to be nurtured as a baby by her mother, and not old enough to have found her own friends via school. In the picture below, Molly leans against the post, excluded by the slightly older kids. Notice the placement of the cat, also looking on from a slight distance. Molly identifies emotionally with the cat.

Other conflict comes from the desire to move to a house with a garden versus leaving all that is safe and familiar.

PLAN

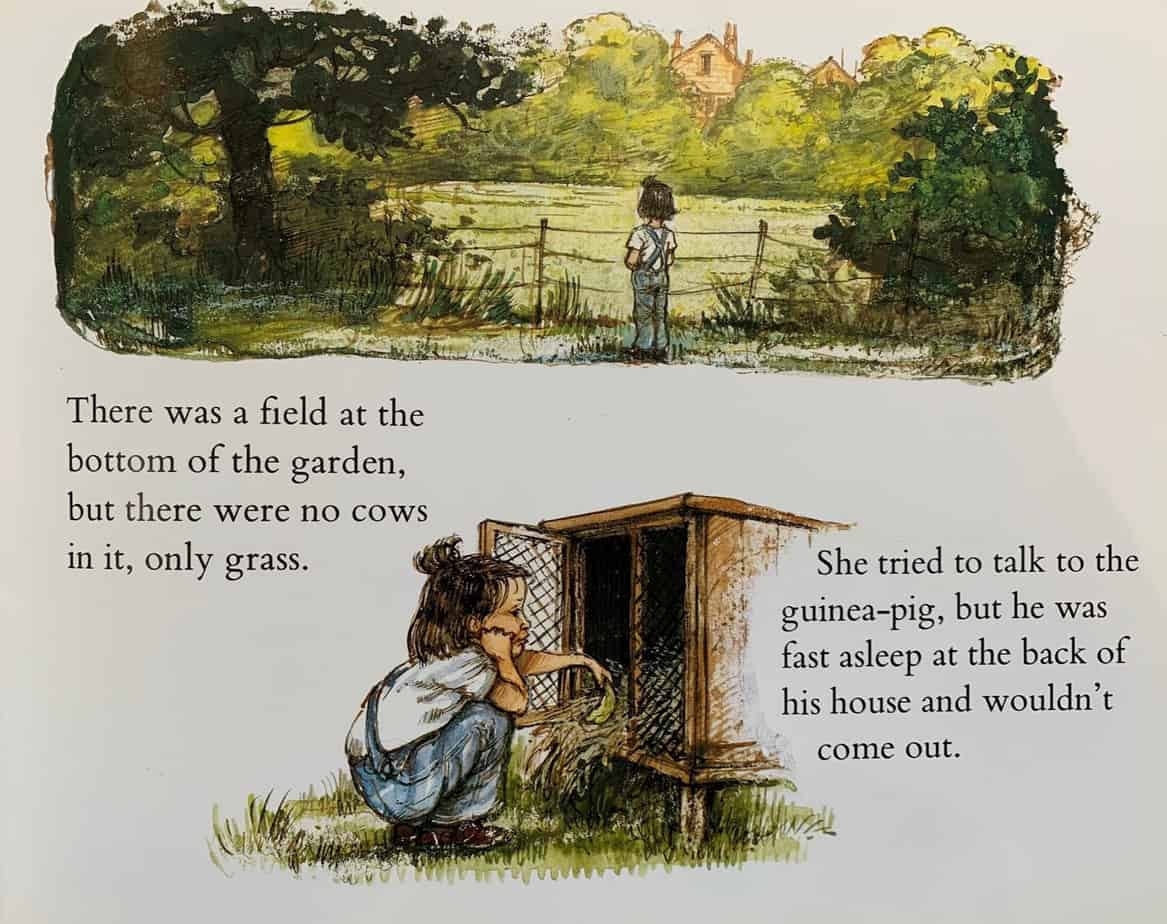

Once Molly gets to her new house she goes exploring. This is pretty much obligatory in a moving house story for children. What I love about Shirley Hughes: She never conveys the illusion that everything can be perfect: ‘There was a field at the bottom of the garden. BUT there were no cows in it, only grass.’ We learn in that one deft sentence that Molly is disappointed, despite the riches around her. The guinea pigs also let her down.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Now there is a portal fantasy sequence, but set in the real world. Molly finds a hole in the fence and enters dangerous terrain. She’s on someone else’s property. She explores the glass house and waters the plants.

ANAGNORISIS

Two ‘identical faces’ peer through the hole in the fence and Molly learns that she now has playmates next door.

What struck me about this: the boy and girl are described as ‘identical’. These days, in toy marketing and even in children’s books, boys and girls are differentiated into a binary. The girls tend to wear something that marks them out as a girl. I’m old enough to remember when this wasn’t the case. Take this Lego advertisement, also from 1981.

The early 1980s were no feminine utopia. In this era of femminism, it was thought that the best way to succeed in life as career women, girls should be encouraged to behave like boys, and working women as working men. This is not a trendy view today, in which the specific soft skills of women are a bit more highly valued (no to the manly shoulder pads, thanks). Feminism has moved on. But the huge advantage to this view was that girls (for a very brief period, until the 1990s) were able to play in comfortable, practical clothes with big pockets and enjoy the same toys as their brothers, without a single thought to whether we were sufficiently feminine. (The same in reverse has not once in history been afforded to little boys.)

Shirley Hughes is right: the faces of the little brother and sister next door are ‘identical’. They all play together as children first and foremost, not as boys and girls. We do see this in some picture books today, but keep an eye on the bestsellers. Gender remains a big dividing factor in the characterisation in children’s stories, even if the message is subversive: girls embarking upon brave adventures, girls being rambunctious rather than demure princesses.

NEW SITUATION

Molly has made friends and now they play together. Notice that Molly’s doll has been cast aside. Her imagination is now peopled with real children. This is always seen as the ideal ending in children’s stories as well as in stories for adults (see Lars and the Real Girl for an adult audience example.) Ideologically, real people trump imaginative play.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I expect Molly will be happy here, and learn lots of social skills with those little kids next door.

Unfortunately for Molly, she probably wasn’t able to afford her own house in the country to raise her own kids, unless she joined a well-paid profession and partnered up likewise.

RESONANCE

There are a great number of stories about children who escape into imaginative play as a way to ward off loneliness and I’ve written several myself. (See The Artifacts, Midnight Feast and Hilda Bewildered, all three.) It must be one of my favourite tropes.

It’s interesting to see how authors depict a child’s imagination. First the storyteller has to decide how the child would have been influenced. This particular preschooler, Molly, imagines castles, dragons, chariots and princesses, and has clearly (somehow) been influenced by Arthurian legends and similar. Probably European fairy tale, in fact.

I used these same influences for The Artifacts, in which my main character Asaf imagines castles, witches, being lost in a ship at sea, but for Midnight Feast I decided to go the less travelled route. The main character, Roya, is experiencing food shortage, and her imagination revolves around her keen interest in cooking and food. I switched it up again for Hilda Bewildered, a real princess who imagines she is an ordinary girl. (A deliberate inversion of little girls who imagine themselves princesses.)

THE IMAGINATIVE LIVES OF GEN Z

If you’re telling a similar kind of story, you might choose for your imaginative child character to delve into the world of chivalry and Romance, though I do wonder if modern children have realistically been exposed to much of that. Which stories are influencing the imaginative lives of Gen Z? The answer is probably computer games, Harry Potter and other massive contemporary influences still under copyright. The trick, then, is to go one back and extract the influences on those things.

In which case, wizards, castles and dragons are probably as imaginatively influential as they ever were. For a truly timeless story, you can’t go wrong with relying on the symbolism of forests, oceans, cities, seasons… universal symbolism in general.