Serena is an example of a film in which the production values and acting talent far exceed the final product. Serena’s obvious symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue make for a film that’s narratively sub-par, but for students of storytelling it’s an interesting case study.

The name ‘Serena’ is meaningful — although the character comports herself serenely in public and in front of her own husband (at least until the novelty of the relationship has worn off) she has a dark underside which we just know is going to come out sooner or later. We’ve heard about her from the gossipy woman at the hunting meet.

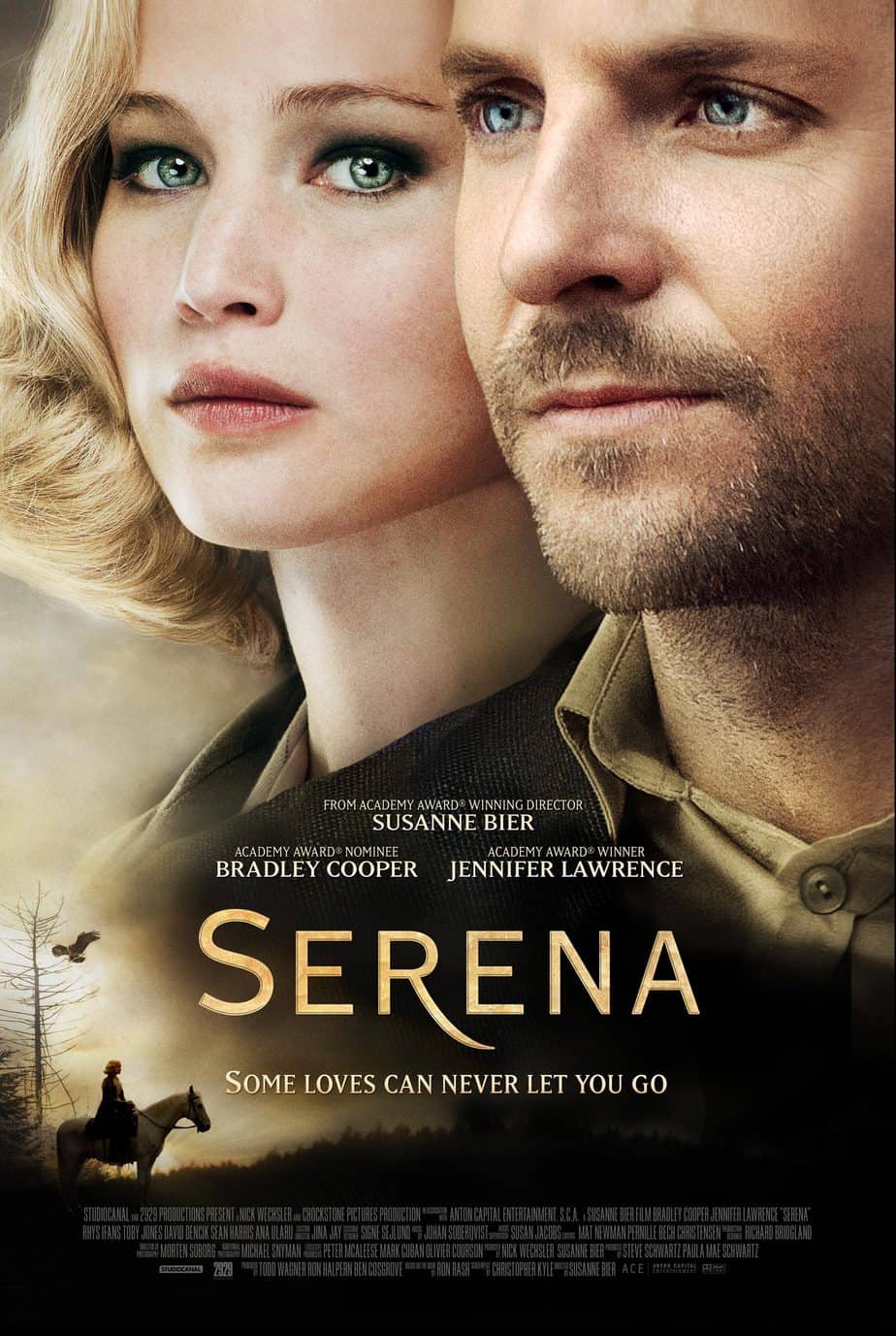

Who is the (tragic) hero of this story? The question is always: Who changes the most over the course of the story? In which case, the answer is both George and Serena. Their relationship is the main character. George becomes Serena and vice versa, symbolised very obviously during the blood transfusion scene in which George is giving his blood to Serena after her haemorrhage. (Hollywood politics are such — and the gender pay gap is such — that Jennifer Lawrence infamously got second billing in this film. Bradley Cooper has since publicly declared he will share his contract details with female costars in future to help with them bargain better with movie bosses who don’t believe in equality.)

In 1920s America the character of Serena is a very unusual woman. She expects her husband’s right-hand man to shake her hand (something even modern men don’t even know whether to do or not with women). She doesn’t seem like an enlightened feminist of the first wave, though, either. She pits herself in direct opposition to the Hillary Swank type woman (Rachel) who, at the story’s beginning, George has already gotten pregnant.

Serena and Rachel are Betty and Veronica types. Casting usually ends up with contrasting hair colours for women. Men can all have the exact same hair colour and skin tone (white) and we’re expected to look at their personalities, but female actors playing in opposition to each other are expected to change the colour of their hair. We do, however, have a red-headed man in this who plays a part in George and Serena’s downfall by taking the incriminating ledger books from the safe.

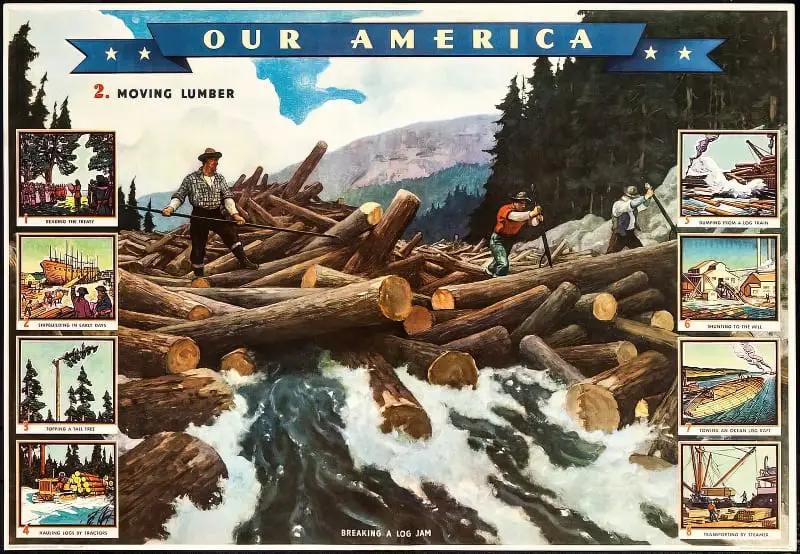

Serena knows from her father’s logging business in Colorado that eagles are useful. They kill snakes, which protects the men. Serena makes a name for herself by becoming the eagle lady, importing a trained eagle (trained by a woman, she specifies) to carry out this exact job. What is the symbolism of the eagle? Could it be that the writer wants us to think of Serena as a harpy — a half eagle, half woman chimera, who swoops in seemingly ‘on the wind’ (though actually on a train). Harpies steal food from their victims while they are eating and carry evildoers (especially those who have killed their family) to the Erinyes (a.k.a. The Furies). Their name means “snatchers”.

We know early on that fire is symbolic. There is much fiddling around with cigarettes and lighters and sitting in front of fires, gazing into them. So it’s no surprise really when it is revealed that Serena bears a scar — an outward manifestation of her psychic wound — on her back. George washes her lovingly in the bath. She tells him, and us of course, the event which wounded her — as a child her house burned down. As she ran away she heard the screaming of all her younger siblings, all of whom burned to death in the fire.

Anyone who has read We Have Always Lived In The Castle by Shirley Jackson may wonder if it was Serena who set the original fire in the first place. Apparently it is strongly implied in the Serena novel that she set the fire in order to end up sole heir. I suspect this story owes quite a bit to Jackson.

The characters are all archetypes rather than rounded. If Serena is a mysterious beautiful woman who flies into town — a modern harpy with an obvious wound which has somehow made her sociopathic. George is a ruthless business man who — I think — we’re still supposed to side with, because he tells us at the town hall that he cares for the jobs of his men. Rachel is a poor country girl whose only way out of abject poverty is to hang around George until he feels guilty enough to hand her money. Buchanan is possibly a closeted and frustrated gay man who is betrayed by his love interest’s getting married. The characters get more archetypal as we move further out from George. A character straight out of a horror film is of course Galloway, whose mother told him as a child that a woman would save his life. When Serena sort of saves him after his hand gets axed he is convinced not only that it’s her, but actually knocks on her front door to tell her husband that he is indebted to her and is in her service forever. It just so happens that he’s been in prison for murder. “He had it coming.”

“He had it coming” is exactly the sort of uninspiring snippets of dialogue found throughout the film. “I have your child inside me,” Serena says to George, upping the stakes when their ‘future’ is at risk. Dialogue exists almost solely to tell the audience what should already be clear: “It’s so obvious now. My friend was never my friend,” says George after Serena and all of the entire audience has already worked that out. After describing the lethal fire of her childhood Serena finishes up with, “After that day I swore that I would never love anyone ever again. I can’t lose you.” Likewise, when Rachel Hermann asks for her job back we are told “If she don’t get a job her and that boy will starve.” With the most rudimentary of historical contexts we already know what a dire predicament Rachel is in, with no social welfare and no husband to support her.

At the end there is a chase scene, as the horror-figure of Galloway is determined to carry out the murder of Rachel and Jacob on Serena’s behalf. Miraculously, George finds Rachel and Jacob hiding at the exact same time Galloway does. He is able to fight him to the death right then and there in the climactic big struggle scene. Another coincidence of timing happens when George is killed by the panther, who might as well be fighting on a stage — all of the men out looking for him arrive just at that exact moment. These coincidences lend a very Old West air to the story. In Westerns symbolism is everything and we don’t question it.

The photo album allows the audience to see into George’s head. We can see him extend allegiance from Serena to Rachel. Did we really need such obvious visuals? The photo album I can stomach. When George actually places the loose photograph of his son on top of his own childhood photo, that’s when I groaned.

In Depression-era North Carolina, the future of George Pemberton’s timber empire becomes complicated when he marries Serena.

copy entered into IMDb

Advertising copy for this film usually says something like George’s trouble began when he married Serena. I would encourage people not to take this at face value. It’s often the case that advertising material for a film is more misogynistic than the story itself, which has the benefit of depth and layers. It is certainly not the case that Serena was the cause of George’s problems. He had already abandoned a woman he impregnated in favour of a more sophisticated one with the potential to add expertise to his precarious fortune. He killed his right-hand man without any help from Serena. This is in fact the story of two disturbed individuals whose union made each of them worse.

This is not necessarily easy for women to watch, even though it has been dismissed as a mere ‘chick flick’ by amateur reviewers on IMDb. The women do not talk to each other. In fact one of them is decidedly laconic, in a way that George finds mysterious and appealing. (The ideal woman is a woman who does not talk.) Both women are motived singularly by their relationship to a man and even the woman at the beginning is a gossipy stereotype who, in Pride and Prejudice fashion, ends up throwing Serena and George together while meaning to do the exact opposite. Serena absolutely falls apart when she discovers she cannot procreate, despite being invested in and motivated by the logging business. A more nuanced story might see her eventually throw her energies into that as a way of moving forward. That’s not what this is, of course. This was always meant to be a tragedy and I have no criticism for that. Instead I’m sick of the same old female tropes, and dismiss Serena therefore as a film for and about women.