Mothers are either held up as paragons of selflessness, or they’re discounted and parodied. We often don’t see them in all their complexity.

Novelist Edan Lepucki contemplates motherhood

Mothers in fairy tales have a way of being absent, typically through untimely deaths (think Cinderella, Snow White or Beauty and the Beast) or thanks to storylines that position them as background characters. Disney’s Disenchanted turns this on its head. Here, at last, we have a fairy tale where mum takes centre stage, as well as left and right, as Good Mother, Wicked Stepmother, and the ever-entertaining and power-hungry Queen Mother.

Disenchanted: Disney attempts to break stereotypes of motherhood only to reinforce them by Vanessa Marr

The evil stepmother is a fixture in European fairy tales because the stepmother was very much a fixture in early European society–mortality in childbirth was very high, and it wasn’t unusual for a father to suddenly find himself alone with multiple mouths to feed. So he remarried and brought another woman into the house, and eventually they had yet more children, thus changing the power dynamics of inheritance in the household in a way that had very little to do with inherent, archetypal evil and everything to do with social expectation and pressure. What was a woman to do when she remarried into a family and had to act as mother to her husband’s children as well as her own, in a time when economic prosperity was a magical dream for most? Would she think of killing her husband’s children so that her own children might therefore inherit and thrive? […] Perhaps. Perhaps not. But the fear that stepmothers (or stepfathers) might do this kind of thing was very real, and it was that fear–fed by the socioeconomic pressures felt by the growing urban class–that fed the stories.

We see this also with the stories passed around in France–fairies who swoop in to save the day when women themselves can’t do so; romantic tales of young girls who marry beasts as a balm to those young ladies facing arranged marriages to older, distant dukes. We see this with the removal of fairies and insertion of religion into the German tales. Fairy tales, in short, are not created in a vacuum. As with all stories, they change and bend both with and in response to culture.

— Amanda Leduc, Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space

We’re born young and helpless. We require a long period of care, wherein we often cannot even clearly articulate what it is that we need (we often hold the fantasy that we can in adulthood, but even that is suspect for many of us). During this long period of need, a mother (or mother figure) both supplies the object of our desires and frustrates our needs. Sometimes she knows what we want, and sometimes she doesn’t. […] heteropatriarchy requires men to be averse to nongenital sexuality. As Freud understands it, genital sexuality posits that someone who has matured will experience desire and pleasure only genitally and only for a heterosexual object-choice outside of the family. Genital sexuality is when you let go of your mother to find your wife.

Nathan Rochelle Duford

No mother is ever, completely, a child’s idea of what a mother should be, and I suppose it works the other way around as well.

Margaret Atwood (cf. Changeling stories)

The only time you truly become an adult is when you finally forgive your parents for being just as flawed as everyone else.

Douglas Kennedy

It is partly a children’s book convention that you write from the kids’ point of view, so you cannot be entirely fair to the parents as well. If you are going to write about children of twelve and thirteen who have totally understanding and marvellous parents, there’ll be nothing to write about.

Gillian Rubenstein

The subject of mothers is apparently very sensitive for Peter [Pan]: “Not only had he no mother, but he had not the slightest desire to have one. He thought them very over-rated persons”. This is rather a puzzling statement, since Peter’s desire is to have Wendy as his mother. But the desire is extremely ambivalent, and the Lost Boys can only speak of mothers in Peter’s absence, “the subject being forbidden by him as silly”. “Now, if Peter had ever quite had a mother, he no longer missed her. He could do very well without one. He had thought them out, and remembered only their bad points.” We know that Peter ran away the day he was born, because he heard his parents talk about what he was to be when he became a man, which was not his intention: “I don’t want ever to be a man…I want always to be a little boy and have fun”.

From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature by Maria Nikolajeva

Frances Spufford writes that characters in fairytales are symbols.

A character in a story exists in particular before it exists in general. A wicked stepmother is a woman before she is a symbol of what a child might fear in motherhood. The story of Snow White therefore says things about gender, and the encounters of daughter, stepmother, father and lover, before it can become a picture of a psychological process.

The Child That Books Built

The following notes draw heavily from the Kid You Not Podcast, Episode 11

The mother in children’s literature is generally ambivalent and ambiguous.

Mothers are all slightly insane.

J.D. Salinger

SANCTIFIED MOTHERS AND EVIL STEP-MOTHERS

The idea of motherhood in Harry Potter and the Other Mother of Neil Gaiman’s Coraline represent two very different but very typical representations of the mother in kidlit. In HP, the concept of the mother is sanctified; the mother died to save Harry’s life. She leaves lingering protection in his veins so that evil characters cannot touch him.

Gaiman’s mother in Coraline is a reworking of a fairytale mother: Stepmothers are used to displace the child’s anxieties and unpleasant feelings for the mother. It’s less threatening for a child to be crossed or abandoned by a step-mother than by a birth mother. Bad mothers tend not to be biological mothers, at least on a surface reading of them.

In young adult literature in the 1940s and 1950s through to the 1960s, parents were assumed to be always right. John Rowe Townsend writes in Written For Children:

In The World of Ellen March, by Jeanette Eyerly (1964) […] a teenage girl, knocked off balance by her parents’ impending divorce, concocts a childish plan to reunite them by kidnapping her little sister. The plan misfires, of course; Ellen is reprimanded by Father for foolish, irresponsible behaviour and realizes that she must “grow wiser, or wise enough to order her own life properly rather than try to make over the lives of her parents.” In other words, the burden of adjustment is on her, and she is at fault for not having the maturity and stability to deal with the situation her parents have placed her in.

John Rowe Townsend

But by the end of the 1960s it was no longer assumed in children’s literature that parents are always right.

In John Donovan’s I’ll Get There, It Better Be Worth The Trip (1969), the hero’s mother is a heavy drinker; his father has remarried, and “when we see each other everything has to be arranged.” Davy’s love goes to his dog and the male friend he’s made at school. In The Dream Watcher, by Barbara Wersba (1968), the hero’s parents are living together, but the father is a pathetic death-of-a-salesman figure and the mother is a dissatisfied, self-indulgent woman who has destroyed her husband and could easily destroy her son.

Written For Children, John Rowe Townsend

But Rowe Townsend writes that the most despicable parents of all in YA are the parents in the books by Paul Zindel. Zindel’s characters tend to be all the same across his work — the teenagers were similar and the parents were all awful.

In the eighties, parental iniquity was no longer a major theme. None the less, parents had been toppled from their former pedestal, and there was no way of putting them back.

Written For Children, John Rowe Townsend

What Makes For A Good Mother?

The bar for good mothers — in fiction as in life — is high. At least, for human ones.

That cat had six letters, and each litter had five kittens, and she killed the first-born kitten in each litter, because she had such pain with it. Apart from this, she was a good mother.

Doris Lessing, Particularly Cats

This observation is far from new, but we’re far more forgiving of animal mothers than of human mothers. What has only recently begun to be talked about is that we are also far more forgiving of human fathers, in part because the job of fathering is so new — it was not so very long ago that ‘to father’ meant to provide the sperm and to provide, offering mentorship as sons grew older. I’m sure there have always been outstandingly paternal examples, but it’s the cultural idea of Fatherhood that I’m talking about.

Marieke Hardy sums it up when describing her own mother:

She was — and remains — a very good mother; open to any and every discussion, and a proponent of creative, generous living at all times. Though she’s never been one of those women described as ‘born to parent’. There’s an expectation that these delightful nurturing instincts set certain females apart from their sisters, draw a line in the sand of compassion that may rarely be crossed. A propensity for tea parties, a ‘way’ with dolls, tending to a scabbed-up knee with concerned frowns: these are the character traits of a very pleasant somebody born to make babies. Those failing to similarly measure up are spoken of in mean-spirited, disparaging terms. ‘She’s not very motherly, is she?’ remains, as a character appraisal, on a par with ‘She takes a while to warm up’ and ‘I just think she really enjoys the music of Jack Johnson.’ Display an iota of awkwardness when playing with a child and you are dismissed, pitied, slotted into the stiff-backed category of Cruella de Vils or wicked stepmother types who would rather skin puppies than do anything so maladroit as nappy changing.

You’ll Miss Me When I’m Dead

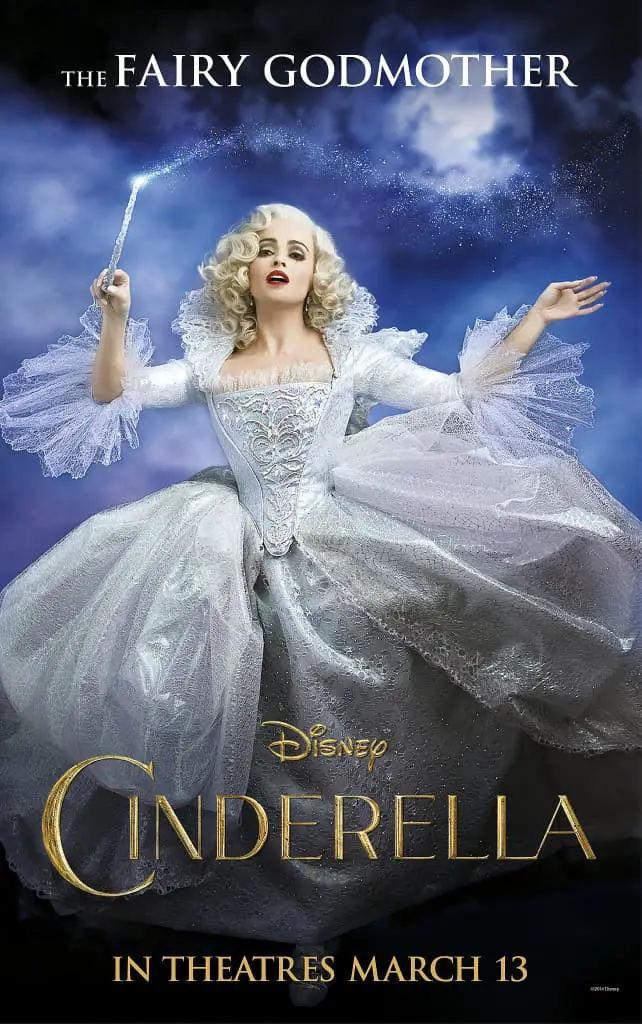

THE FAIRY GODMOTHER

This is the ‘white’ side of the mother — the side who is protective, generous, devoted and gentle.

MOTHERS AND PICTUREBOOKS

Desire for the mother is at the heart of much of the literature of childhood, particularly in books for young children. [Picturebooks] evoke the body of the mother and early states of desire.

Roni Natov

The modern world manifests an overwhelming human yearning for wholeness, oneness or integrity, a yearning apparent in oral appetites, sexual desire, religious fervour, physical hunger, “back to the womb” impulses [and] death wishes.

Sarah Sceats

It’s striking to see that the mother in old comics — especially French and Belgian ones — will be a part of the domestic space, but not acknowledged in the language of the text. In these stories the mother is a chattel. In many picture books this is also the case. This normalises traditional motherly roles. The reason she is in the background is because she provides the comfort and security, almost metonymous for the home (much as a kitchen can be), and therefore important in the home-away-home pattern. The more discreet her presence, the more ideological the idea that mothers belong in the home.

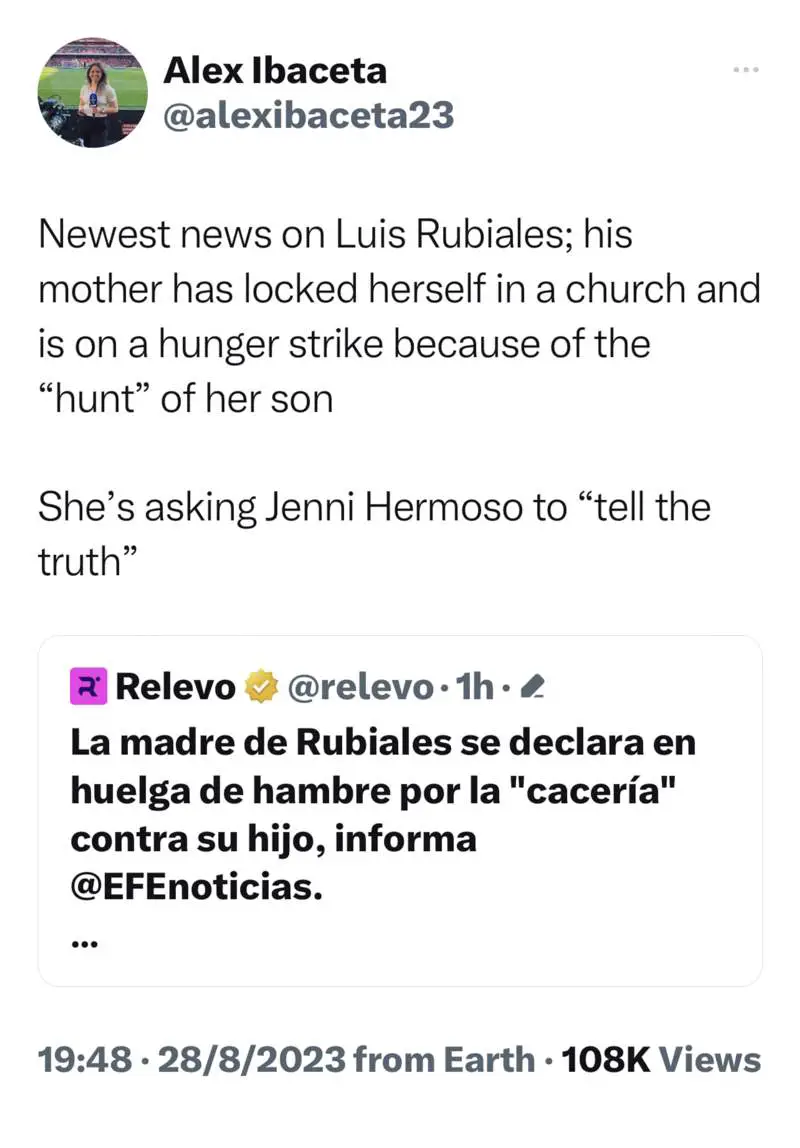

THE ABSENT MOTHER AND THE STRANGELY PRESENT MOTHER

This fairytale split is replicated even in very modern stories, including Harry Potter. There is another thing to do with parents: Get rid of them completely. Pippi Longstocking could not have had her adventures with the interference of parents, and neither could most of Enid Blyton’s characters. Pippi does have a father and in one book he features as King of the Cannibals. But she couldn’t have a typical mother. The mother is generally the more anxious, controlling side of the parents, with the father being more distant. Mrs Darling in Peter Pan is far more worried than Mr Darling about what is happening to the children. But adventures can more readily happen with the father present in the background.

We still view motherhood as mandatory and fatherhood as voluntary.

Levin, co-founder of The Parents Village

Linguists have noticed that when turned into verbs, ‘to mother’ means something very different from ‘to father’.

THE DEAD MOTHER

Death is another kind of absence. This time, the mother is not absent because she’s not worth mentioning but rather the direct opposite: The dead mother is the ultimate absence that is a presence. In most books this is the case, and definitely in the Harry Potter books. The parents may as well be alive.

Jacqueline Wilson provides plenty of examples of absent mothers, e.g. Double Act.

Mimi by John Newman is another example. The mother’s absence is the epicenter of the whole story. The father is there in body but doesn’t step in to fill the domestic gap, until other mothers turn up and force him into the role of parent.

In Neil Gaiman’s Fortunately, The Milk, the working mother is required to leave the family home at the beginning of the story because she needs to attend a conference. She fills the freezer with meals and tells the father to remember to stock up on milk, as that’s the only thing she hasn’t been able to micromanage before she leaves. Once she is gone, the children run out of milk, presumably because the father is useless. However, the father redeems himself because while he is out buying milk he has a remarkable adventure. This story relies on the stereotypes that working mothers are hyper-organised and men with working mothers for wives hide behind their newspapers and let her pick up the slack at home. It is yet another story in which the mother must be disappeared before the father can have some real, carnivalesque fun with his own children.

WHY ALL THE DEAD MUMS?

There’s something inconceivable about losing your mother, yet it’s all over children’s literature. Death of mothers in fairytales made sense; it was prudent to prepare children for death because it happened so frequently, but now the number of dead mothers in children’s stories is disproportionate.

See also: Why all the orphans in children’s literature?

THE RULE THAT MOTHERS MUST LOVE THEIR CHILDREN

Drugs, alcohol, sex: These plots are all plentiful in YA fiction, but mothers who do not love their children? This may be the last taboo. Children often hate their mothers, but not the other way around.

The Illustrated Mum, also by Jacqueline Wilson, is another book about an absent mum but only because she doesn’t come home to sleep at night. This is a source of intense anxiety for the narrator. The mother lives with bipolar disorder. This is one of the most powerful of Wilson’s books. The children take it upon themselves to look after the mother. It plays on so many anxieties you have as a child. The mother doesn’t take care of the children and is unpredictable. She can be compared to the fairytale type of mother in Coraline. But ultimately, the mother in The Illustrated Mum does love her children. This is important: No matter how hopeless/useless/hated the mother in children’s literature, she pretty much always loves her children. The Tracy Beaker series (also by Jacqueline Wilson) also features a mother with mental illness.

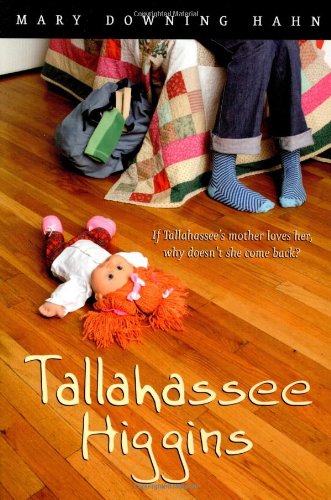

In Tallahassee Higgins by Mary Downing Hahn, the mother leaves the little girl in the care of someone, leaves again, comes back and so on. There’s always the presumption that there is something wrong with the mother’s mind, rather than that she is a bad person. She is simply dysfunctional as a person. Tracy Beaker is slightly different in that you never see the mother. Tracy’s mother doesn’t do anything awful; she is simply not there.

A good example of an outright evil person who is also a mother is Mrs Coulter in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. It is revealed quite early in the series that her mother is a distant/cold/unpredictable person. She is evil, a child killer, a bit of a witch. But gradually in the third book there is a Sleeping Beauty type of twist in which she starts taking an interest in her daughter. She does love her child, rescuing Lyra from the guillotine. In the end she does sacrifice her own life to save her child. Again, a very bad person still turns out to be a good mother.

Mrs Coulter has something in common with the Other Mother in Neil Gaiman’s Coraline — both are Stepford wife tropes who have literal robotic elements. In Coraline the mother is gradually revealed as being a metallic, robotic insect on the inside. Lyra kisses Mrs Coulter on the cheek and her lips taste metallic afterwards. Later when Mrs Coulter gets angry at the journalist she emits the smell of burning metal.

Another truly bad mother is the mum in A Solitary Blue by Cynthia Voigt (1983). This is the tale of four children abandoned by their selfish mother in a carpark. But again, the mother does love her children. She simply can’t look after them. The main character Geoff deifies his mother in her absence. The story ends with Geoff accepting that she is who she is and he decides to have nothing to do with her. His relationship with his mother can be read as almost inappropriately sexual. As in The Illustrated Mum and Northern Lights, the mother is considered beautiful and glamorous.

Another rare example of a mother who leaves her son can be found in the film Lean On Pete.

THE TROPE OF WAITING FOR AN ABSENT MOTHER

Bambi is a classic example of this: Bambi waits for his mother but she never comes back. Instead, his father turns up.

See also the Missing Mom trope at TV Tropes

TYPES OF MOTHERLY SACRIFICE

First is the literal sacrifice of the mother’s own life, more common in fantasy than in realistic fiction.

Then there is symbolic sacrifice in which the mother sacrifices her life as an independent woman. There’s an interesting genesis to this. If we consider the young female characters who give birth during their teenage years in the course of YA stories, the young mothers, upon popping out babies, tend to suddenly develop this overwhelming maternal instinct. Twilight is a good example of this. Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman is the same. All the young mothers normalise the maternal instinct. Melvin Burgess’s Junk goes even further in this regard. The baby offers a redemption from the lies she has been living. She realises she has to get out of prostitution and living on the street. Pregnancy is now a salvation. This is a strong statement about the maternal instinct.

See the following papers:

From Basketball To Barney: Teen fatherhood, didacticism, and the literary in YA fiction by Helen Bittel, which is about the popular subgenre of YA — the teen pregnancy and parenting novel.

Stories of Teen Mothers: Fiction and non-fiction by Cynthia Miller-Coffel

The sacrificing mother is related to the ‘smothing mother’, often represented in children’s fiction by children who are overfed/overweight. This mother has no fulfilment of her own — she lives for and through her children.

In the book, Dahl blames the mother for failing to curb Gloop’s appetite: ‘And what I always say is, he wouldn’t go on eating like he does unless he needed nourishment, would he? It’s all vitamins, anyway.’

Mrs Dursley’s overbearing, infantalising love is the counterpoint to Harry’s complete lack of motherly love.

TABOO TOPICS EVEN TODAY

Abortion is rarely postulated in young adult literature. But here is a Goodreads list of young adult books in which a character actually goes through with an abortion (rather than simply considers it).

As for breastfeeding, given how it is to be encouraged, and how much of it is presumably going on in homes, there is remarkably little of it going on in Western picturebooks. In films for kids out of Hollywood, it is actually taboo. This is what makes the breastfeeding scene in Wolf Children quite transgressive to a Western audience. At one point we even see the areola. I have not once seen that in a picture book for Western children.

MOTHERS AND FOOD

Food, especially sweet, rich food, often metaphorically represents the body of the mother in popular culture and that the desire for such food includes a subconscious yearning for the restoration of the primal relationship with her.

Carolyn Daniel, Voracious Children

If you read carefully, you’ll notice that a lot of stories feature male protagonists with nurturing mothers who provide food. Note that in Where The Wild Things Are, for instance, Max returns to his room and there is a meal waiting. (Note that it’s still hot.)

You can find an example of a mother giving maternal comfort to a girl in Phillip Pullman’s Northern Lights, when Ma Costa folds her great arms around Lyra and presses her to her breast. Generally, though, girls in children’s literature don’t derive quite the same amount of comfort from motherly types as boys. Carolyn Daniel speculates:

- Maybe girls aren’t thought to need mothers so much as boys do

- Maybe because girls are thought to become mothers themselves one day they’ll again be able to experience the mother-child relationship (albeit from the opposite side).

I’m going to add that there’s probably some weird homophobic stuff going on there, too. And also the female maturity principle.

It probably goes without saying, but the breast stands in metonymically for the mother.

Good mother = food/love/comfort

Bad mother = lack of food/lack of love/lack of comfort

Mothers in stories use food as a means of power exchange. Good mothers provide eaters with sustenance/power/energy. In exchange, good mothers are content with the emotional satisfaction she receives from providing the food. (And never complains about having to cook it all.) But the smothering mother provides food that poisons the eaters. She drains them of vitality/power/subjectivity. Instead of feeding, she absorbs this energy from the child. An example of that is the mother figure (actually the aunt) in Tom’s Midnight Garden, who is a great cook but provides Tom with far too much rich food. He feels imprisoned inside their small house, in quarantine because of measles, and doesn’t appreciate the food.

MOTHERS OF NARCISSISTIC SONS

RELATED

An article about the transformation of the mother in American-Mexican lit by Megan Parry

Roles Of Mothers In Disney Media from Wikipedia

Which Disney Mom Are You Most Like? one of those stupid quizzes, from Poptastic

10 Best Bad Mothers In Literature (for adults) from The Telegraph

A list of Parent Tropes at TV Tropes

It’s Not All about Snow White: The Evil Queen Isn’t that Monstrous After All a paper by Cristina Santos

TOP TEN WORST PARENTS IN TWEEN LIT BY AMY ESTERSOHN

13 Reasons Why Clay’s Mother Is The Fucking Worst from BuzzFeed. I agree, even as a mother myself, that Clay’s mother as depicted by the Netflix show was excruciating.

11 of the Best Moms in Children’s Literature from Brightly

THE MOTHERS OF HILDA BEWILDERED

Is the ‘mother’ in Hilda Bewildered good or evil?

There are two mothers in Hilda Bewildered. First is the Queen, the mother of Princess Hilda. Then there is the ‘mother’ at the Tropical Hotel — an equally cold character whose motivations are not immediately clear.

Readers are trained by traditional fairytales to regard this mother as evil because of her appearance: Her features are masculine, she dresses in black. Her hooked nose is reminiscent of witches’ noses, as is her grey, unadulterated hair. That she is depicted knitting, in a grandmotherly type pose, is an irony which serves to highlight her un-grandmotherly nature.

When the mother locks Hilda in the ‘closet suite’, this is an obvious trespass upon Hilda’s freedom, but when the police arrive we see that this imprisonment is partly for Hilda’s protection. Is it cruel to lock Hilda up for a few days if the alternative is being locked up for life?

When the mother says, ‘Take this cursed jewel, far, far into the wild. Fling it into the deep,” what is she advising? If the ring is a symbol of beauty, given to some and not others by accident of birth, she is telling her daughter to let go of the beauty ideal. There are two ways to deal with the beauty ideal when you’re far from that: You can reject it outright (as the mother has done) or you can reinterpret beauty itself, taking it for yourself by changing the way you think about the world. This is what Hilda intends to do. She imagines herself as beautiful even though by luck of birth she does not conform to the generally accepted beauty standards. In the image-conscious, celebrity-focussed world of this story, nobody is about to endow Hilda with any worth; she must either reject it altogether or find it from within.

If the reader interprets the mother as the “witch” or “evil-stepmother” analog of traditional fairytales, what does that say about:

- How readers of picturebooks are trained to correlate beauty with goodness in picturebooks and illustrated stories

- How we prejudge characters we meet in real life

- The importance of “beauty privilege”

- The false dichotomy between “good” and “evil” mothers

The mother at the Tropical Hotel as Threshold Guardian

Threshold Guardian entry at TV Tropes

In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic structure for storytellers & screenwriters, Christopher Vogler describes the ‘threshold guardian’.

In stories, Threshold Guardians take on a fantastic array of forms. They may be border guards, sentinels, night watchmen, lookouts, examiners, or anyone whose function is to temporarily block the way of the hero and test her powers. The energy of the Threshold Guardian may not be embodied as a character, but may be found as a prop, architectural feature, animal, or force of nature that blocks and tests the hero. Learning how to deal with Threshold Guradians is one of the major tests of the Hero’s Journey.

Threshold Guardians are not the big, bad enemies but can be likened to a fox at the hole of a bear’s cave, who keeps animals from wandering into the cave while a bear is hibernating, kicking up a fuss if there’s trouble, alerting the bear to danger.

When a hero encounters a Threshold Guardians, she can either power on forward or retreat. The Threshold Guardian tests a hero’s resolve to enter a new world.

Vogler explains that the main function of the Threshold Guardian is to test the hero. Often in stories, the hero ‘gets into the skin’ of the Threshold Guardian, quite literally by, say, dressing up as guards to get past the guards.

Threshold Guardians are not threatening enemies but useful Allies, and ‘early indicators that new power or success is coming. Threshold Guardians who appear to be attacking may in fact be doing the hero a huge favour’.

Artist, writer, and accomplished cook Rob Chirico talks about growing up with an Italian mother who would rather be anywhere but the kitchen. In fact, he wrote an entire book about it, “Not My Mother’s Kitchen.” In today’s discussion Rob gives Italian-American cooking its deserved place as a cuisine separate from classic Italian and explains why.

The Myth of the Italian Mamma

Header painting: Benjamin Leader – The Young Mother hearth