What Is A Moral Dilemma?

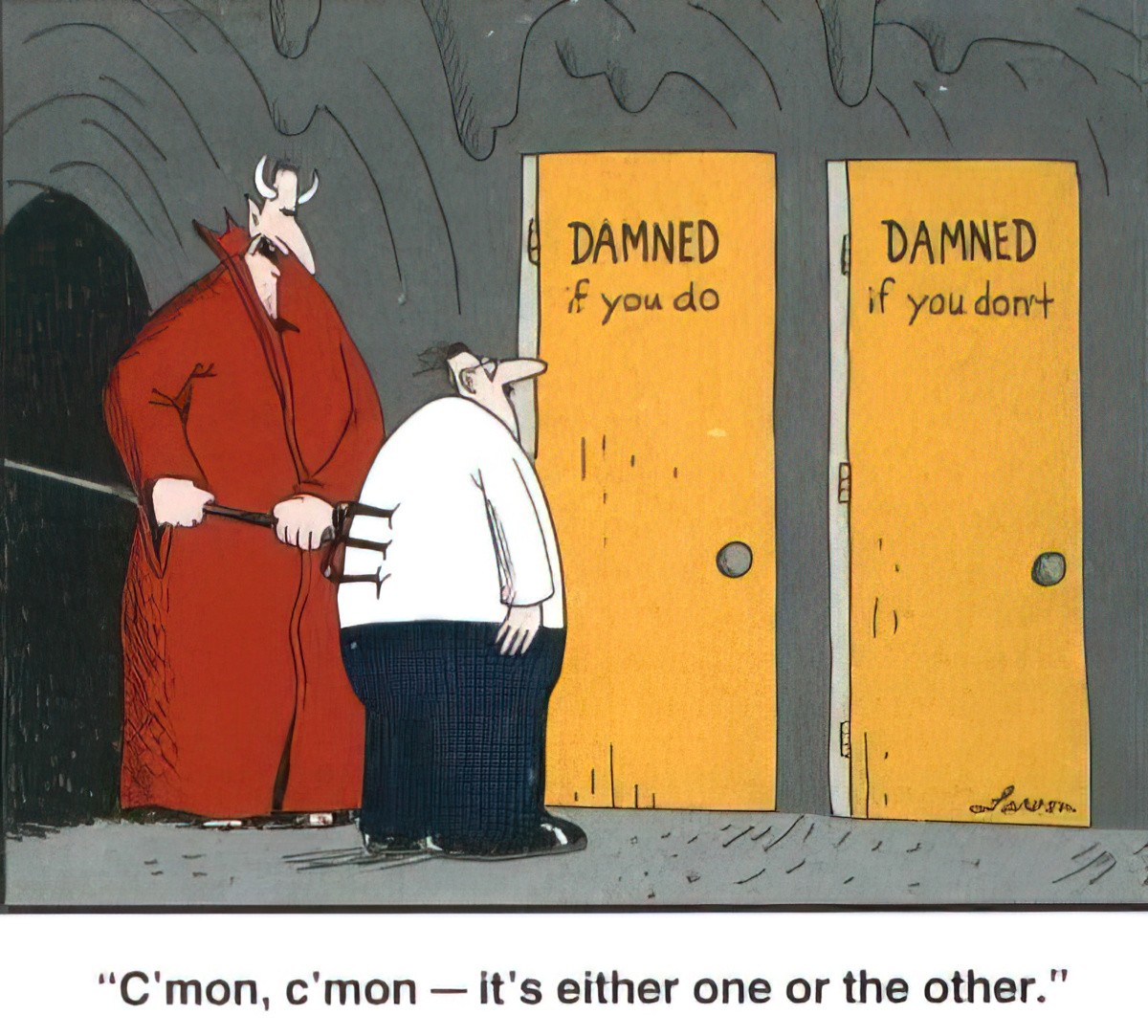

Philosophers are especially concerned with moral dilemmas, and ask the following question: Is it possible to do a morally wrong action in order to do what is morally required?

Various branches of philosophy disagree on the answer to that question. Some believe the question itself contains a paradox, rendering the question itself insensible. Gertrude Anscombe was an influential English analytic philosopher who went so far as to say that even considering this question seriously was evidence of a corrupt mind.

Modern moral theorists (generally) dismiss the question. Consequentialist philosophers judge morality by the consequences of someone’s actions, and they too are generally uncomfortable with the idea that good can result from immoral actions. Then there are the deontologists (a.k.a. duty theorists) who judge morality of action by someone’s motives. Likewise, they aren’t a fan of the idea that immoral actions can also be moral. They all say it’s a dangerous proposition.

Then you’ve got political philosophers, who tend to see the world a bit differently, understanding that politicis is all about making the best of impossible situations.

In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil.

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (Lesson Nine)

Any man who tries to be good all the time is bound to come to ruin among the great number who are not good. Hence a prince who wants to keep his authority must learn how not to be good, and use that knowledge, or refrain from using it, as necessity requires.

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

This view is based on the understanding that two things motivate people best: love and fear. (Fear works better than love.) The Machiavellian view is that a good leader learns how to use fear to motivate people.

Unfortunately, immoral and unethical people can justify their evil decisions to themselves and others by arguing that they had no choice but to make an unfortunate moral decision, but they made the best of a bad situation.

Storytellers and narrative theorists are another group of people deeply interested in moral dilemmas. The best storytellers understand that the most interesting stories require characters to make decisions, between bad and worse, or between terrible and catastrophic.

Donald Maass explains the difference between a ‘dilemma’ and a ‘MORAL dilemma’:

A dilemma is a choice between two equally good or two equally bad outcomes. A moral dilemma elevates such a choice by giving two outcomes equally excellent, or excruciating, consequences not only for a protagonist, but for others. A dilemma is a situation in which none of us likes to be caught, but in which we all sometimes find ourselves. A moral dilemma is a situation nobody wants, and which few must ever face, but which is terrific for making compelling fiction.

Donald Maass

Using Donald’s distinction, not many children’s books of middle grade level and below feature moral dilemmas. The vast majority feature dilemmas, relatable because they are faced by all of us over the course of growing up: Do I sit with my old friends at lunch or with these shiny new friends? Do I follow my parents’ instructions or do I try something different? Though we might still call these ‘moral’ dilemmas if we wish.

Luke has never been to school. He’s never had a birthday party, or gone to a friend’s house for an overnight. In fact, Luke has never had a friend.

Luke is one of the shadow children, a third child forbidden by the Population Police. He’s lived his entire life in hiding, and now, with a new housing development replacing the woods next to his family’s farm, he is no longer even allowed to go outside.

Then, one day Luke sees a girl’s face in the window of a house where he knows two other children already live. Finally, he’s met a shadow child like himself. Jen is willing to risk everything to come out of the shadows – does Luke dare to become involved in her dangerous plan? Can he afford not to? Luke finds himself faced with an impossible choice.

Below, a character from Star Trek monologues about moral dilemmas, offering an excellent definition and example, and why so many stories are pyrrhic victories for the characters who have faced impossible choices. The scene below is basically a Self-revelation scene. At the beginning of a story a character makes the best bad choice. This drives them towards some kind of self-revelation, which will probably involve the realisation that their actions caused harm, and they must now learn to live with that fact.

Robert McKee is another storytelling guru who has this to say about fictional moral dilemmas, though I don’t believe everyone is a moral person. Some people (and characters) are antisocial and amoral, sometimes immoral.

The choice between good and evil or between right and wrong is no choice at all

Human nature dictates that each of us will always choose the “good” or the “right” as we perceive the “good” or the “right.” It is impossible to do otherwise. Therefore, if a character must choose between a clear good versus a clear evil, or right versus wrong, the audience, understanding the character’s point of view, will know in advance how the character will choose.

A thief bludgeons a victim on the street for the five dollars in her purse. He may know this isn’t the moral thing to do, but moral/immoral, right/wrong, legal/illegal often have little to do with one another. He may instantly regret what he’s done. But at the moment of murder, from the thief’s point of view, his arm won’t move until he’s convinced himself that this is the right choice. If we do not understand that much about human nature–that a human being is only capable of acting toward the right or the good as he has come to believe it or rationalize it–then we understand very little. Good/evil, right/wrong choices are dramatically obvious and trivial.

True choice is dilemma. It occurs in two situations. First a choice between irreconcilable goods: From the character’s point of view two things are desirable, he wants both, but circumstances are forcing him to choose only one. Second, a choice between the lesser of two evils: From the character’s view two things are undesirable, he wants neither, but circumstances are forcing him to choose one. How a character chooses in a true dilemma is a powerful expression of his humanity and of the world in which he lives.

Robert McKee, Story

As pointed out by McKee, a dilemma isn’t philosophically interesting unless the character faces a true choice. A choice between a ‘good outcome’ and a ‘bad outcome’ is no choice, either. The empathetic main character will simply make the good choice. Story over. (No story to begin with.) The interesting narrative choice must force two bad outcomes.

The character must get their hands dirty.

What Does It Mean To Get One’s Hands Dirty?

A person gets dirty hands when they violate an important moral value to bring about a lesser evil in moral conflict situations.

Stephen de Wijze, political philosopher

Dirty hands scenarios contain inherent paradox: Those who make difficult decisions resulting in lesser evil receive praise for doing what’s courageous and difficult. However, that same person becomes morally polluted acting as they do.

How To Keep Dirty Handed Characters Empathetic?

Storytellers use all sorts of tricks to create audience empathy but in the case of stories which require empathetic characters to act badly, the opponent is particularly important.

In real life as in fiction, our actions in life are circumscribed by the evil acts of other people. Therein lies the difference between an empathetic person and an unempathetic person: Empathetic people will only act badly when they are forced to act for an outcome of ‘lesser evil’.

In this situation, an opponent might be a natural circumstance. For example, the leader of a country might require citizens to basically be on house arrest, destroying the economy to a large degree, but with the outcome that many lives are saved due to a nasty virus. Without the pandemic situation, a leader who curtails freedoms and destroys the economy is simply a villain.

Everyday Dilemma, Or Impossible Choice?

Janice Hardy calls the moral dilemma the ‘impossible choice‘. Hardy advises writers to include at least one impossible choice per story, even if the story isn’t overtly about that (e.g. Sophie’s Choice). If we think in terms of ‘impossible choice’, then choosing to sit with new friends instead of old friends then sounds impossible: If you sit with your old friends you could squander a chance to make extra friends. But if you sit with your new friends you might lose your old ones, since childhood is tribal. If you follow the rules about being nice to everyone, how do you deal with that covert bully who is never nice to you? Ignoring won’t work. Childhood is chock full of impossible choices.

An ‘everyday dilemma’ has a clear ‘correct move’ and the correct move will be heavily implied within the world of the story. Take the short clip below, a classic Sesame Street animation. The character has a dilemma: to pick the pretty flowers, or not? The animators anthropomorphise the flowers and make them shrink away, signalling to the viewer that to pick the poor flowers would be the incorrect choice. The flowers he has previously picked wilted immediately. This is not a moral dilemma; this is an ‘everyday dilemma’.

Moral Dilemmas Give Stories Emotional Impact

Karl Iglesias in his book Writing For Emotional Impact has this to say about moral dilemmas:

Dilemmas create emotional anguish for characters, which in turn challenges readers to consider what they would do if the dilemma were theirs. Our anguish may not be as acute, as we’re one step removed, but we twist our hands anyway. That is, we twist them if the dilemma is truly difficult.

Dilemmas, then, work best when the stakes are both high and personal. When one choice is morally right, it will win out unless it is offset by a different choice that is equally compelling in personal terms. Law versus love. Tell the truth or protect the innocent. Be honest or be kind. When there’s no way to win in a story, the winner is us.

The more difficult the decision your character has to make, the more you’ll engage the reader in thinking about it and therefore compel them to read on to find out how the story turns out.

Parables always feature a moral dilemma. The main character faces a moral dilemma, makes a bad decision then suffered the unintended consequences.

To take the schoolyard bully example, it is morally right to ignore a bully. That’s what kids are told to do. But in reality, ignoring bullies doesn’t work. It may feel personally right to quietly take revenge, or at the very least, to assert your own position in the pecking order by doing something that displays your own strength.

Moral Dilemmas Create Mystery

Mystery in story is always good. Not just in the mystery genres, but in every single story.

Karl Iglesias recommends the following for creating mystery around characters:

Create a mysterious past

Special abilities, secrets. Make the secrets hurtful and embarrassing or dangerous. Your character should be willing to do about anything to protect them.

Create a mysterious present

Why is the character behaving in this particular way? Maybe they say something surprising in dialogue. The balancing act for writers is, these actions have to be both surprising and consistent with attitudes and desires.

This is where the moral dilemma comes in. As soon as you create a fork in the road for your character, this creates curiosity, anticipation and uncertainty in the reader. The mystery is: What on earth will this character do? The harder the choice, the more interesting it is to see the character’s decision.

Create a mysterious future

What will be revealed about the character and when? How will the reader be surprised?

We might use the word ‘ghost‘ to describe ‘mysterious past’. The word ‘hook’ or ‘dramatic question’ is often used to describe mystery in the present and future.

Examples Of Moral Dilemmas In Stories For Adults

Dirty hands happen in all areas of our lives, so all genres of stories, in all settings, moral dilemmas feature large, from the relatively minor and personal to the massive and catastrophic.

Here’s why moral dilemmas have more consequence in stories for adults compared to those in stories for children: The more power the actor, the more catastrophic the impossible choice.

Political philosopher Stephen de Wijze explains why in a Philosophy For Our Times Podcast: “Doing Wrong To Do Right”. Politics is the ‘natural home’ of the moral dilemma.

Politicians face dirty hands scenarios daily. Politics is about protecting people from enemies, external and internal. Leaders also pick up the messes of their predecessors, cleaning up evil messes others began. Violence, lying and manipulation is so often the means to a political end. Politics thereby becomes all about compromise and choosing lesser evils. Politics actively rewards lying and dissembling. These are attributes required by politicians, at least so far in history, and probably into the future. There rarely exists any political situation free of dirty hands, and people who become leaders must have the ability to live with the consequences of their actions. (I believe this explains why leadership attracts sociopathic neurodivergence.)

The more power the actor/character/leader, the more devastating the impact of their moral decisions.

Here are a few examples of clear and obvious moral dilemmas in stories for adults — clear because the consequences are so dire.

DRAMA

No one talks about moral dilemmas in fiction without mentioning Sophie’s Choice, in which the central moral dilemma is in the film’s title. In this story, the moral dilemma is the main thing. It’s right there in the title. In desperate circumstances, on the spur of the moment, a mother must decide between sacrificing her son or her daughter. This decision is presented as a flashback story using her present non-wartime life as a wrapper.

Ned Stark from Game of Thrones faces a terrible moral dilemma in season one. But Ned is a good man whose very goodness destroys him. That’s not all: In storytelling terms, the end of Ned Stark’s life is not such a high stakes outcome (except for Ned and his family, of course). What raises the stakes and turns Game of Thrones into an epic high fantasy drama: Everyone else who depended on him are now going to suffer. Ned Stark was no politician. He wasn’t wily enough; not sufficiently willing to make a morally bad choice for greater longterm good. Throughout the rest of the Game of Thrones story the audience sees the unfolding of Stark’s failure, ie. how he refused to get his hands dirty. Calamity ensues. Hundreds of thousands die because of Ned’s Jesus-like goodness.

Chernobyl, the drama written by Craig Mazin, is full of the worst kind of moral dilemmas, made all the worse because they were faced by people in real life 1986. Do we sacrifice three men without telling them we’re sending them to their death, or sacrifice 60 million lives? (A real life example of The Trolley Problem in philosophy.) Do I act as whistleblower and tell the truth about my country, or keep quiet and hope they fix the next potential disasters before they happen?

Jeffrey Eugenides’ book of short stories Fresh Complaint is about men who don’t know how to behave in a more egalitarian world. Eugenides makes sure to include many moral dilemmas in the stories, fully understanding how moral dilemmas create great drama:

It’s sort of, you’re caught in the middle of this thing, you want to redefine what it means to be a man in our time, and then going along with that has to involve a lot of self-exposure, and a lot of recrimination and regret for your behaviour. At the same time, there’s maybe some resistance to being told how you’re supposed to behave. So the characters are caught between being good and being bad. That makes for more energetic fiction, when you have someone of two minds trying to figure out a problem, as opposed to being really sure about his way and his conduct.

Vulture

The lesser known film Albino Alligator from 1996 explores the dilemma of a woman having to kill an innocent man in cold blood so that she can survive a hostage situation. Compare this to a film such as Kidnap (2017) in which Halle Berry’s young son gets taken. Here there is no moral dilemma as she goes all out to get her son back, causing serious car accidents and even killing a cop. In this story it is taken for granted that a mother WOULD go all out for her son.

CRIME Shows

The detective/crime genre is great for presenting police officers with daily moral dilemmas.

Crime writer Jo Nesbo has this to say about the approach he takes to his stories:

I give my protagonists moral dilemmas and force them to make a choice. And I try not to be the judge of the choice they make. One of the big questions I try to ask is, what is free will? What is morality? Is it something God-given, or is it a framework that society has imposed on us to make us more efficient?

Even in stories for children, writers must ultimately let the audience decide whether the character was right to have made the decision they made.

Another excellent example is 24, starring a character named Jack Bauer.

Jack Bauer is a fictional character and the lead protagonist of the Fox television series 24. His character has worked in various capacities on the show, often as a member of the Counter Terrorist Unit based in Los Angeles, and working with the FBI in Washington, D.C. during season 7.

Jack Bauer, Wikipedia

Each episode of 24 is all about how Jack Bauer saves the world from evil people. He must do terrible things to try and prevent catastrophe from happening. Every episode features a massive moral dilemma (a.k.a. dirty hands problem a.ka. impossible choice).

Dexter is another example, this time from the point of view of a sociopathic killer. The twist? He uses his sociopathic power to kill ‘for good’, only killing despicable people. We are to assume that once these despicable people are dead, there is less evil in the world overall. 24 and Dexter are immensely popular shows, demonstrating how audiences love impossible moral dilemmas; the more impossible, the better.

PSYCHOLOGICAL HORROR

In the Japanese psychological horror Dark Water, a mother must decide between staying with her own daughter (in which case they may both be killed), or sacrificing herself to mother the little girl ghost, thereby leaving her own daughter without a mother.

Moral Dilemmas In Stories For Children

Child characters typically have much less power than adults, therefore their moral dilemmas impact on their own personal lives — on their family, friends and neighbours. Moral dilemmas are less often a feature of picture books, many of which are carnivalesque, but start to loom large in middle grade stories. Young adult fiction aligns more with adult fiction in the severe outcomes of moral dilemmas, genre dependent.

FREEDOM OR CONFORMITY?

Sticking with the wolf theme, in the Japanese feature-length anime Wolf Children, the mother of two were-children must make a series of tough decisions about what to do with her offspring. One of the first: When they get sick, does she take them to the vet or to the doctor? Next, does she stay in the city and force them to live like humans, or does she take them to the country and let them explore their wild sides?

In the Society, officials decide. Who you love. Where you work. When you die.

Cassia has always trusted their choices. It’s hardly any price to pay for a long life, the perfect job, the ideal mate. So when her best friend appears on the Matching screen, Cassia knows with complete certainty that he is the one…until she sees another face flash for an instant before the screen fades to black. Now Cassia is faced with impossible choices: between Xander and Ky, between the only life she’s known and a path no one else has ever dared follow—between perfection and passion.

Four months ago: Sara Zapata’s best friend disappeared, kidnapped by the web of criminals who terrorize Juàrez.

Four weeks ago: Her brother, Emiliano, fell in love with Perla Rubi, a girl whose family is as rich as her name.

Four hours ago: Sara received a death threat…and her first clue her friend’s location.

Four minutes ago: Emiliano was offered a way into Perla Rubi’s world—if he betrays his own.

In the next four days, Sara and Emiliano will each face impossible choices, between life and justice, friends and family, truth and love. But when the criminals come after Sara, only one path remains for both the siblings: the way across the desert to the United States.

The story of Peter Rabbit sums up a central dilemma of childhood—whether one should act naturally in accordance with one’s basic animal instincts or whether one should do as one’s parents wish and learn to act in obedience to their more civilised codes of behaviour.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

Japanese feature length anime Wolf Children is also about the choice between the restriction of civilisation or the freedom of the dangerous wild.

KINDNESS OR PRAGMATISM?

In Anne of Green Gables, Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert face a tough moral dilemma. They need someone who can perform traditionally masculine tasks to keep their farm running as the head into old age. But the orphan who turns up at the train station is a girl. They don’t need a girl. So, do they send her back, even though she clearly brings them such joy, and is so grateful to be on Prince Edward Island? The consequences for Anne Shirley are huge, but minimal to nothing for everyone else. This is therefore a ‘low stakes’ moral dilemmas as far as moral dilemmas go. (Contrast with Ned Stark’s moral dilemma in Game of Thrones, the results of which impact everybody in the world of the story.)

TO SAVE A LIFE OR PERHAPS SAVE MANY?

In The Iron Giant, Hogarth faces a tough choice. Does he report a potentially life-destroying giant to the authorities, or does he keep the giant secret and try to turn him into a benevolent entity?

TO SHARE OR NOT TO SHARE?

In “We Found A Hat” by Jon Klassen, two tortoises find one hat. They both want the hat. Only one tortoise can wear the hat. Do they fight for the hat? Do they take turns with the hat? Something else?

To lie or not to lie?

Lying and truth telling are hugely prominent themes in middle grade books, and especially in literary middle grade (the kind which appeals equally to adults). Developmentally, this is when young readers start to question black and white rules about telling the truth.

A story like Wolf Hollow features a moral dilemma, to do with telling the truth or not in order to protect someone. Interestingly, Wolf Hollow was originally written for adults, and revised for children when an editor saw a position for it on the children’s book market.

Similarly, in Lenny’s Book Of Everything by Karen Foxlee, Lenny thinks she discovers something (or someone) important and wonders if and when to tell her mother and brother about it. The mother and brother are preoccupied with bigger (health) issues, which is partly why Lenny keeps it to herself.

Anne Shirley faces moral dilemmas of her own. She has been taught not to lie, yet she finds herself having to do exactly that when she is forced to apologise to Rachel Lynde even though she’s not the slightest bit sorry. In the end it is Matthew who teaches Anne that sometimes it’s best to say the right thing to smooth things over, even when you don’t mean them. For Anne, it’s the choice between being true to oneself and doing what’s expected. This is part of her coming-of-age arc, since we must all learn this social custom, throwing away black and white notions about when it’s okay to lie.

Personal Versus Moral Decisions

Thidwick The Big-Hearted Moose is weighed down by all these creatures living on his antlers but when shooting season begins he has to choose between saving them and being free of them himself. This is the classic moral choice versus personal choice, as distinguished by Karl Iglesias, quoted above.

To break the rules or not to break the rules?

This is also a really popular moral dilemma in children’s books, because sometimes parents and teachers dish out terrible advice. It might be because they don’t want their child to get into trouble by prioritising the personal over the moral. Often as not, it’s because the parents are too old to understand (or remember) the social intricacies that are specific to the school years.

Lindsay and Sam’s father in Freaks and Geeks is so hopelessly out of touch with his teenage daughter that any advice he gives her is taken to comical extremes at the dinner table. In other stories, the adult authority figure may dish out quite sensible advice which nevertheless doesn’t work in the real world. Children start to realise this from about the middle of primary school.

Laura Ingalls wonders whether to let Jack loose on the Indians in Little House On The Prairie. In the next book, On The Banks Of Plum Creek, she is about to disobey her father and approach the river when she is distracted by a badger. In both cases she confesses her ‘almost’ crime and receives a minor punishment. Later, when Laura’s mother tells her to give her precious doll to another younger girl, Laura must decide whether to obey her mother or not. She does, but the girl treats her doll badly. Laura finds the doll in a puddle, brings it home and the mother apologises. Ma then fixes it up so it’s as good as new.

As a real life example, my 9-year-old daughter has a friend who was recently held hostage in the girl’s toilet (in a scene that reminds of something straight out of Bridge To Terabithia). This has led to tears, and the girl blocking the door simply won’t budge. The school rule: Hands off. No touching at all, ever. Advice that actually might work to disrupt the power struggle going on: Barge past anyway, and if she won’t move of her own accord, too bad for her. My daughter’s friend’s real life dilemma is, does she barge past the door-blocker, bending school rules about not touching others in anger, or does she stay in the toilet and cry, cementing the social hierarchy to her detriment?

Stories dealing with the issue of bullying are well-placed to explore these moral dilemmas with nuance that school authorities themselves are unable to provide. In fact, children’s literature is currently going through a period in which adults in general are not to be trusted. This is a feature of the dystopian novel, which made a comeback at the beginning of the 21st century. Amanda Craig has this to say about this kind of children’s book:

Many are quite brilliantly plotted and written, and I recommend them, especially for reluctant readers of 11+, even if, like vampires and demons they are becoming too familiar. Children enjoy imagining how they might behave in such adventures, and the usual blend of action, romance and moral dilemma does no harm. But there are other kinds of novel being published which do worry me.

Amanda Craig

In other words, dystopian novels can be useful for the moral dilemmas they present — and in apocalyptic scenarios, these dilemmas will be a matter of life and death.

Avoiding Overt Didacticism

This advice applies especially to children’s writers, perhaps. We’re going through a period where overt didacticism in children’s books is a big no-no. I push back on that a little below but first, an important distinction:

Narrative closure is not necessarily the same as thematic or ideational closure.

We might call the closure of plot a ‘narrative closure’.

We might call the other kind of closure ‘hermeneutic closure’. (Hermeneutic basically equals interpretive.)

Writers generally tidy up the plot in a narrative (but not always — Hitchcock’s Vertigo is one famous example).

But even if you tidy up all your plot threads to create a satisfying conclusion, that doesn’t mean you should tidy up ideas. You, as writer, don’t have to come down on one side or the other of the moral dilemma you yourself set up:

Your theme should take the form of an irresolvable dilemma, so you should give both sides equal weight for as long as possible until the climax. The trick is to come up with a finale that addresses the conflict and makes a concrete statement about it, without definitively declaring one side right and the other wrong. … [In your ironic and ambiguous ending] a statement is made about the dilemma, but its’ not permanently settled. You have something to say, but you don’t have something definitive to say. You have a point, but your point is untidy. You’re leaving room open for uncertainty and ambiguity, because that multiplies the meaning.

Matt Bird, Secrets of Story

But are children’s storytellers allowed to leave morality hanging? (When I say ‘allowed’, will morally ambiguous endings get published by the Big Six publishing houses, and when they do, will they find an enduring audience?)

This relates closely to a post I’ve already written about punishment in children’s literature. Children’s books very often come down on one side by punishing the characters who made the ‘wrong’ moral choice. A lot of genre fiction for adults is just the same — in crime novels especially, the rule of the genre is that the murderer gets caught (though it’s possible to blend crime with other genres and create something different).

While contemporary children’s books are said to be far less didactic than books from The First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, you’ll find they still contain messages — the messages simply seem more subtle. It all comes down to who gets punished.

There is still very much a taboo against rewarding behaviours considered bad by a popular, conservative audience.

The Gendered Nature Of Moral Decisions

Writers should be mindful of the gendered nature of this question. Girls are acculturated differently, to be kind and self-sacrificing. When female characters in children’s books make huge sacrifices we are reinforcing that message. An Australian picture book in which a female character makes a huge sacrifice for the sake of a male character is the Nick Bland book The Very Cranky Bear. The sheep shaves off her fluff to make the bear happy, but the story ends there. We don’t see how uncomfortable she is in the cold cave without her wool to protect her. Perhaps this is connected to the fact that sheep are regularly shorn, and in Australia where there are lots of sheep, we don’t really consider that a burden on the sheep. (If we didn’t shear sheep they’d grow ridiculously woolly, since that’s the way we’ve bred them.) However, it’s worth subverting gendered expectations where possible, in which case it’s necessary for writers to ask:

- Why have I gendered my characters like this and not like this?

- Can this self-sacrificing creature be gendered male?

- If the self-sacrificing creature is gendered female, is she always sacrificing herself for the sake of a male, or can she at least help another female character or get something out of the situation for herself?

I’ve no doubt there are race issues related to the presentation of moral dilemmas as well.

FURTHER READING

Using crisis to reveal character by September Fawkes

The Cabin at the End of the World (2018) by Paul Tremblay and The Migration (2019) by Helen Marshall explore the prospect of choosing a loved one’s survival over the preservation of humanity as a whole. These texts are set in worlds defined by two very divergent but fast encroaching Apocalypses, whether this is expressed via the characters’ isolation in a North American cabin or in Oxfordshire as they become cut-off from the world by increasingly extreme weather conditions. The small family of Cabin are held hostage and forced to make an impossible choice—pick one member to die or the world

All You Need Is Love?: Making the Selfish Choice in The Cabin at the End of the World and The Migration by Rebecca Gibson

ends—whereas the family of Marshall’s text are faced with a longer battle to protect the family unit against a mysterious and horrifying epidemic targeting teenagers, eventually revealed to be a new stage of evolution, at the cost of preserving human civilisation as they know it.

A CHARACTER IS MORE LIKELY TO MAKE A BAD CHOICE IF FATIGUED

No matter how rational and high-minded you try to be, you can’t make decision after decision without paying a biological price. It’s different from ordinary physical fatigue — you’re not consciously aware of being tired — but you’re low on mental energy. The more choices you make throughout the day, the harder each one becomes for your brain, and eventually it looks for shortcuts.

Do you suffer from decision fatigue? from the New York Times

Philosophers often consider the (infamous) ‘Ticking Bomb’ scenario. (Infamous because it is thought to lead the thinker towards a certain conclusion.) The scenario requires the subject to consider if torture is ever justified.

This fictional scenario actually happened in Germany in 2002, when 11-year-old Jakob von Metzler was kidnapped by a 27-year-old law student. Police found the kidnapper, but the kidnapper refused to reveal the location of the boy. A police officer threatened torture, and the location of the boy was revealed. However, the boy was already dead. Germany, because of its 20th century history, is particularly careful around matters of torture. What happened next should probably not surprise us.