Monster Pet! is a 2005 picture book written by Angela McAllister and illustrated by Charlotte Middleton. The story is designed to get young readers thinking about the responsibility of caring for a sentient creature. A body swap plot is used to that end, though I suspect more empathy derives from the facial expressions on the poor little locked up mouse than from the body swap experience, which in a picture book, challenges the adult book-buyer’s ideas of what a picture book should do; This one is slightly creepy. The School Library Journal had this to say:

The theme of not caring for a pet, and then the reversal with Monster forgetting to feed Jackson, is disturbing, and the dream ending feels forced.

Is this story disturbing because the assumed audience is very young? Does the dream ending feel ‘forced’ because it doesn’t work, or because adults are sick of the ‘I woke up and it was all a dream‘ trope?

I should disclose that I’ve utilised a body swap scene myself in our middle grade picture book app The Artifacts (2011), in which the main character keeps a caterpillar in a jar. A tap on the screen reveals the human character now in the jar, and the boy is now a giant caterpillar. We also received feedback that the story is ‘spooky’, but we also received feedback that middle grade readers using it in class sessions loved it. (The app was rated by them.) This suggests that this variety of animal-human body swap creepiness is accepted in middle grade stories but not in stories for the younger set. Another question needs to be asked: If it’s creepy to see a tiny human behind bars, is it not equally creepy that we keep pets in cages, or wild animals in zoos?

STORY STRUCTURE OF MONSTER PET!

PARATEXT

Jackson has always wanted a pet. Something BIG and WILD and EXCITING! So imagine his disappointment when his dad brings home…a hamster.

Not giving up hope, Jackson names his little bundle of fluff Monster, and tries to teach him to be the outrageous pet he really wants. But when Monster won’t fetch sticks or climb trees, Jackson loses interest in caring for him altogether, and it takes a surreal taste of role reversal to show Jackson the error of his ways.

Complemented by Charlotte Middleton’s edgy illustrations, Angela McAllister’s monstrously funny story will have readers roaring with laughter, while it delivers an important message about the rewards and responsibilities of owning a pet.

marketing copy of Monster Pet!

‘Roaring with laughter’ suggests the marketing team didn’t fully appreciate where this book sits. Some body swap stories can be funny, utilising hat-on-a-dog type humour that appeals to very young children. But this one is definitely not in that category. I suspect mishandled marketing.

My 2005 copy of this book is called Monster! (without the Pet). I wonder if the title was changed because a book called simply ‘Monster’ is too generic and therefore difficult to find. 2005 marked the start of a big change in how I buy books, and how I’m guessing other people buy books — I used to visit Whitcoulls and Borders; I now search online. I rarely use online bookstores to browse, instead visiting digital bookstores already knowing what I want. This change in book buying habits is probably led to more specific and unique titles.

SHORTCOMING

Jackson has clear moral shortcomings: He solipsistically wants a pet who behaves as he wants him to behave. Jackson has this in common with the main character of This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers.

When he gets the pet and abandons him, he shows a lack of empathy which, frankly, borders on troubling. I think this, too, is partly what lends the book creepiness.

DESIRE

Jackson’s wish for a pet is established on the first page, but what does his desire for a pet say about his deeper needs?

He seems to need entertaining. He is interested in novelty and bored by the realities of cleaning out a hamster’s cage and the routine of delivering fresh water and food. He soon desires novelty again and this, I deduce, is why he moves on.

OPPONENT

The hamster is small, helpless and locked up so does not provide a story worthy opponent until it gets out and the body sizes are inverted.

PLAN

The marketing copy suggests this book is meant to be more of a carnivalesque adventure for the reader, in which case it would be fun (or at least novel) to imagine being the size of a hamster for a while. This is no carnivalesque fun, at least not in a The Cat In The Hat kind of romp.

In common with a carnivalesque tale, however, Jackson has no plan as such. He is now entirely reliant upon the fantasy creature doing their thing. He is at the monster pet’s mercy.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The gigantic hamster wants to teach Jackson how to store food in his cheeks, and other things a human wouldn’t want to do. Since this is how Jackson treated the hamster, the dream is basically a revenge plot.

Jackson is eventually locked up without food or water. A horrific, concentration camp scenario, especially when one of the characters is rendered human (and not, say, a Smurf).

ANAGNORISIS

Jackson has a clear revelation — after waking up from his nightmare he has gained insight into how it might feel to be locked in a cage with no one looking after you.

I agree with the SLJ reviewer that this seems forced. I don’t believe it’s because revelation happened in a dream; I believe it’s because it wasn’t earned. There is no clue in the story about what it was that provoked the dream.

I’m working on the theory that dreams don’t come from some higher plane; if dreams are revelatory, that’s only because they’re a manifestation of our deep subconscious.

NEW SITUATION

This story utilises the trick of changing a character’s name to indicate another kind of change — in this case the change from ‘Monster’ to ‘Fluffy’ signals a change in Jackson’s attitude. This is where the story leaves us, without a fun wink you might expect from a fun carnivalesque story (rather than a creepy one).

I’m not a huge fan of this ending because I enjoyed the opening irony of Jackson naming a tiny, helpless creature ‘Monster’.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

In storybook world Jackson has learned his lesson permanently, though as an adult reader I doubt Jackson’s need for novelty is suddenly trumped by post-nightmare guilt. His newfound sense of empathy and responsibility may be short-lived.

RESONANCE

It’s possible that a body swap story helps a child imagine what it’s like to be a neglected hamster. That seems to be the main raison d’être of body swap stories.

Stories about kids who want pets without fully understanding the responsibility continue to be popular. A successful, comedic example is The Pigeon Wants A Puppy by Mo Willems. By making the pigeon an animal, Willems removes the hierarchy of human looking after animal, and inverts the power dynamic at the end. Monster Pet! feels more serious partly because the main character is a human boy.

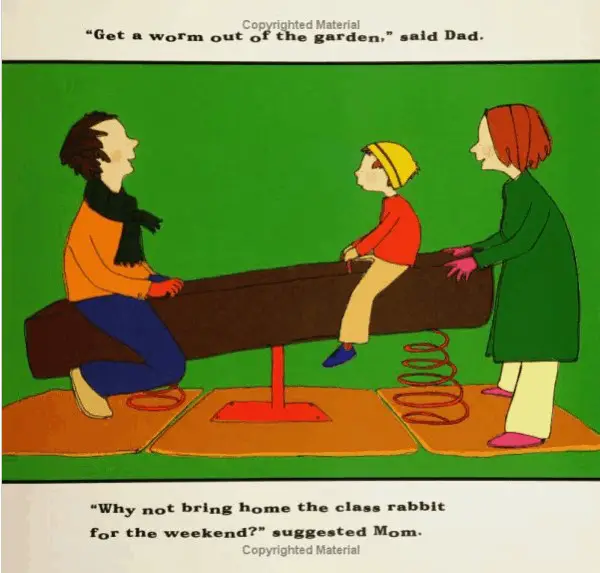

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

This particular green is so clearly the green of Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown that I think of Goodnight Moon whenever I see it.

Characters are drawn in minimalist style. The advantage is that the family of people could map onto a wider variety of people — the child sees themselves in the book. These characters have unusually small dots for eyes (in contrast with an illustrator such as Jon Klassen, in which the eyes are main features). A disadvantage to drawing with such minimalist style is that even a picture book requires sentences like this:

“I promise,” said Jackson, with a grudging look.

That said, if Monster Pet! had been drawn in a realistic style, the creepiness would have been too much to bear.

Lauren Child utilises a similar style of illustration, evident in her Charlie and Lola series: a mixture of minimalist, loosely drawn characters combined with backgrounds made partly of collage. Fill expands beyond the outlines, suggesting the naive sensibilities of a child artist.

Unlike Lauren Child’s work, the words in this story are cleanly separated from the art work by sectioning off the tops and bottoms of the pages. (Even as an adult reader, I find Lauren Child’s integrated, curvy, wavy text difficult to read.)

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

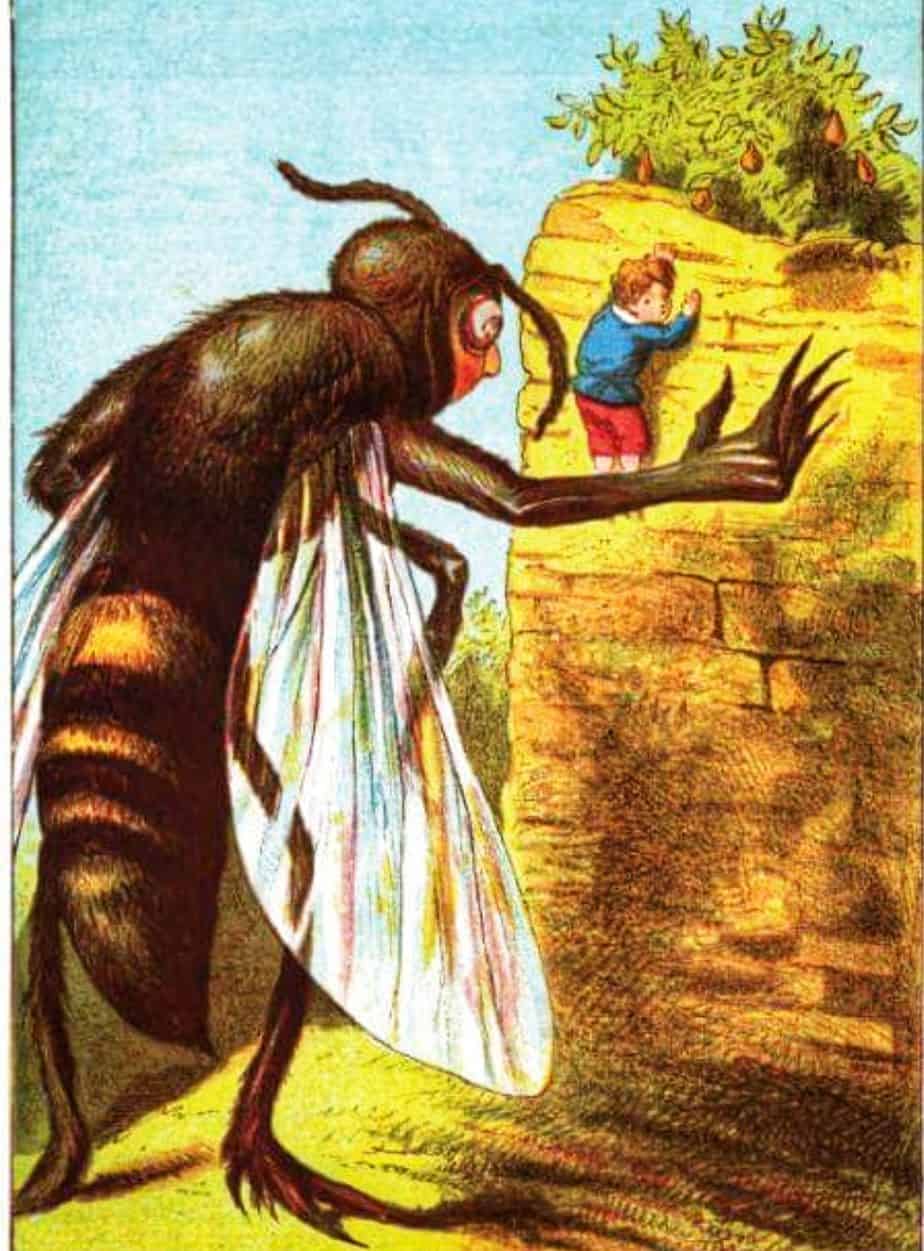

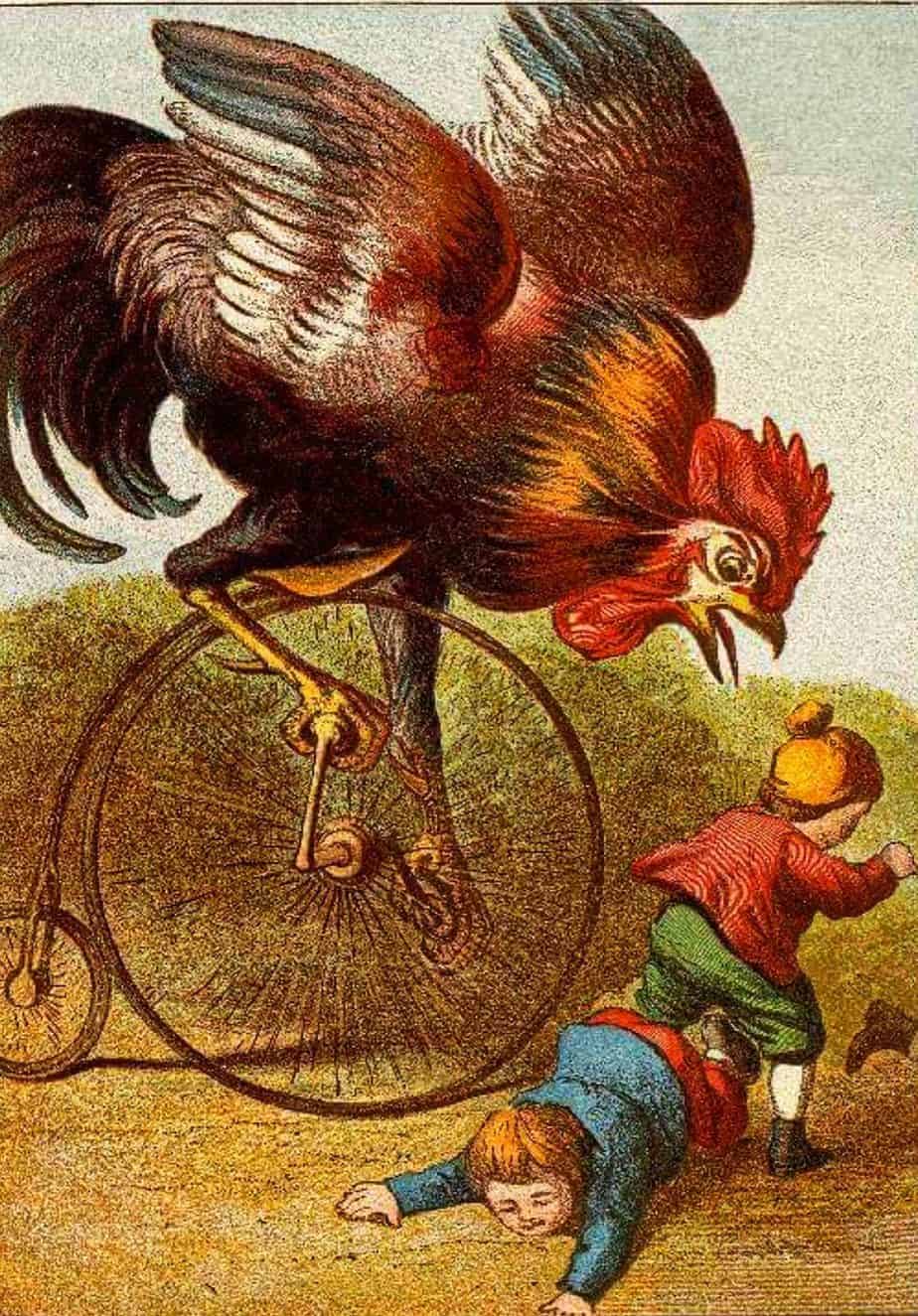

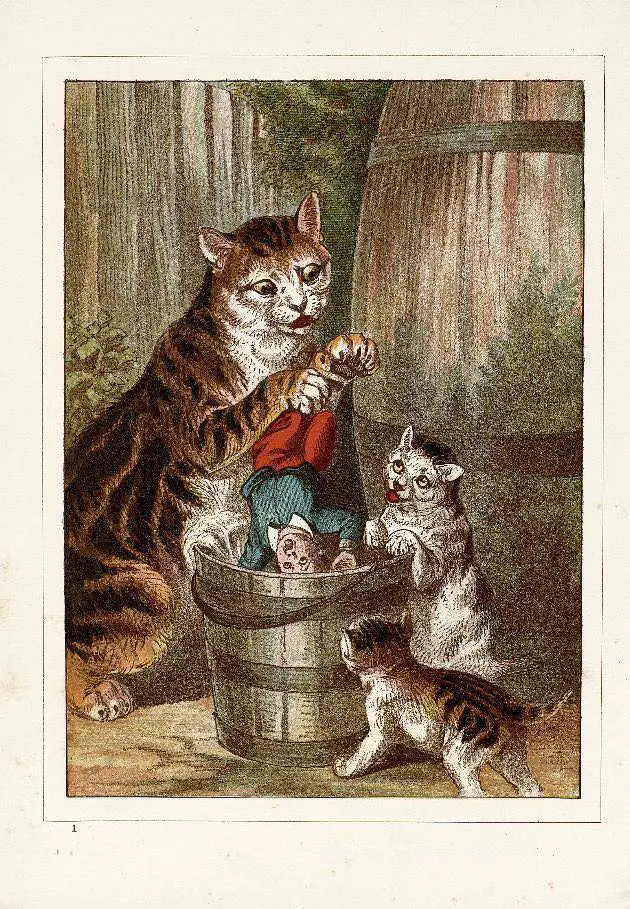

The trope of the abused animal getting revenge is pretty old. Take The Tribulations of Tommy Tiptop dating from 1893, created by someone known as ‘M.B.’. In this much earlier story, a boy called Tommy gleefully abuses helpless animals and has nightmares of those same animals abusing him.

Another similar plot can be found in Lulu and the Brontosaurus by Judith Viorst and illustrated by Lane Smith. In this metafictive chapter book about a spoilt but feisty brat, Lulu goes into the forest to find herself a brontosaurus. (Her parents would buy one for her, but can’t find a brontosaurus.) Once she finds him, the brontosaurus wants to keep her as HIS pet, and he does, until she learns her lesson… that no matter how well he keeps her, it’s the loss of freedom that’s the problem. In this way, the message of Lulu and the Brontosaurus is similar to the message in This Moose Belongs To Me, although the author of Lulu is harsher on Lulu’s moral weaknesses than Oliver Jeffers is on the boy who decides he’s going to keep a wild animal for a pet.