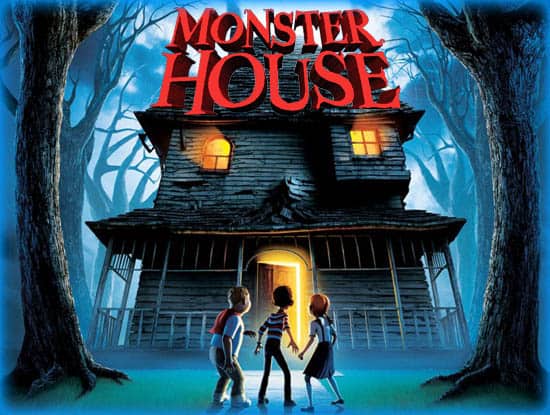

Monster House is a 2006 animated feature length film for a middle grade audience. The script was written by Dan Harmon and Rob Schrab. Harmon and Schrab had collaborated on Laser Fart previously, a film which I have not seen and will not be adding to my watch list. Monster House is already 12 years old, but the animation still looks pretty good. It was animated at a time when actors were just starting to be used as models, which is why this looks better than The Polar Express. The one thing significantly improved by modern processing power is hair. Inability to depict hair and skin is why Pixar decided to make their first animated film about toys. The hair on the characters of Monster House looks plastic, like you get on a 1980s Ken Doll, compared to what you see in, say, Brave, of 2012, in which hair is almost a character in its own right. (Animators have since gotten over their hair obsession, I think. Now hair is just hair!)

Screenwriter Harmon has been working in television since Monster House, notably on Rick and Morty. He also lists The Simpsons in his credits. Schrab has also been working in TV, most notably on The Sarah Silverman Program. Basically, these are youngish American comedy writers with a male sensibility.

MONSTER HOUSE STORY STRUCTURE

Genre Blend of Monster House

Monster House is a genre blend of Adventure and Comedy. Monster House is also a haunted house story, though it’s not DJ’s own house that is haunted, but the creepy old mansion across the road. Though not listed as a horror, this story borrows horror tropes. Horror and comedy are a surefire hit, if done correctly. Jump scares have to be genuine jump scares, and the writers have to know which scenes are to be taken seriously and which are a deliberate lampoon. Monster House achieves this balance, with genuine scares for the younger audience, followed by funny scenes which bring the audience back into safety… for a while.

Unfortunately, the popular horror genre has some highly problematic tropes, and the writers of Monster House borrowed those, too.

Monster theory states that the characters viewed as villains or monsters reflect cultural unease or prejudices. Often, this leads to the vilification of those who defy gender roles, and perpetuates this vilification in the media. […Many] stories place a heavy emphasis on female sexuality as a particularly awful form of deviance.

As for ‘adventure’, what does that mean for writers? It’s more of a director’s term than a scriptwriter’s term. Adventure means several things:

- The characters will leave the safety of home, in which case we’re often talking about mythic structure. In this case, ‘leaving home’ means ‘walking across the street’, but it’s still really scary.

- Lots of scenes written with spectacle in mind.

SHORTCOMING

At the beginning of the story DJ has been monitoring the creepy house across the road. He has noticed that when toys land on Nebbercracker’s front lawn they disappear. Something spooky is going on there. The problem is, he doesn’t know what’s going on and because he lives across the road, it’s in his best interest to find out. Things get personal when his best friend Chowder loses his expensive basketball. Then DJ thinks he accidentally killed Nebbercracker. This makes him invested.

DESIRE

Under the surface, DJ wants to prove himself a man. (This is of course related to his major Shortcoming, that he is a powerless boy.) At the beginning we hear his voice crack. He considers himself too old for Trick or Treating. He says he’s too old for a babysitter — he’d be just fine alone with his parents off on holiday. This allows for some good, ironic comedy in which it is revealed that DJ is mostly still a child. He sleeps with his bunny rabbit, he is freaked out by small things (though justifiably freaked out by big things).

In some ways, DJ’s wish to be manly is shown by his desire to be childlike. Unfortunately, as almost always happens in stories about boys written and funded by men, DJ’s wish to be manly is also shown by his desire to be non-feminine. (Hence an actual girl has to come along. More on that below.)

Note to all writers everywhere: The opposite of ‘man’ is not ‘girl’. The opposite of ‘man’ is ‘boy’. Girls do not exist to affirm your heterosexual manliness.

OPPONENT

Chowder and DJ are similar to Jeff Kinney’s Greg and Rowley. Greg is the pessimistic skinny one while Rowley is the chubby, childlike one. (More childlike than DJ.)Chowder is DJ’s Opponent in his mission to be considered more adult. Chowder is full of enthusiasm for trick or treating, and likes to play computer games and eat junk food. By hanging around with Chowder, DJ won’t be considered a man. Before they leave for their weekend away, the parents (especially the mother) are also opponents in this regard. DJ’s mother babies him in the most embarrassing fashion, making inappropriate remarks about his changing adolescent body.

Note that Jeff Kinney probably got this successful trio ensemble from J.K. Rowling, who probably got it from someone else again. The romantic opponent is Jenny — a Hermione character who is smart and organised and who drives the plan. Both DJ and Chowder compete for Jenny, at first objectifying her. We are encouraged to laugh at them as they try to impress her and fail. This, too, is the Wimpy Kid formula, in which girl characters are not quite human, considered a separate species (by the boys, and by extension, by the audience). Girls are also depicted as inherently ‘smarter’: more bookish, more scathing, more wily and underhanded. Jenny is an example of The Female Maturity Principle.

DJ’s babysitter, Zee, initially appears to be The Babysitter From Hell. She is depicted as a duplicitous goody-two-shoes who is actually into heavy metal and stoner boyfriends. The male scriptwriters have given her some pathetic, pseudo-feminist lines to make us despise her even more. Zee is actually on the same side as DJ though, because they have the same goal: To do their own thing in the house while they each leave the other alone. The babysitter’s stoner boyfriend represents the other side of the babysitter — together they form a slightly dangerous team. The audience knows this pair won’t be there to help the boys out should they need it. Parents and parental influences are safely out of the way in this story.

I have just listed the ‘inner circle’ of opposition, but the Big, Bad Opposition at first appears to be Nebbercracker, and is then revealed to be his house. This pairing is an example of a character who IS his house. At least, that’s how it’s set up:

When trespassed upon, the place reacts in a variety of antisocial ways: The lawn can suck things underground, and the facade takes on an unnaturally human visage, with two upper windows as eyes, a peak above the porch roof as a nose and the front door as a mouth, out of which rolls a lengthy tongue-like carpet with frog-like snatching ability.

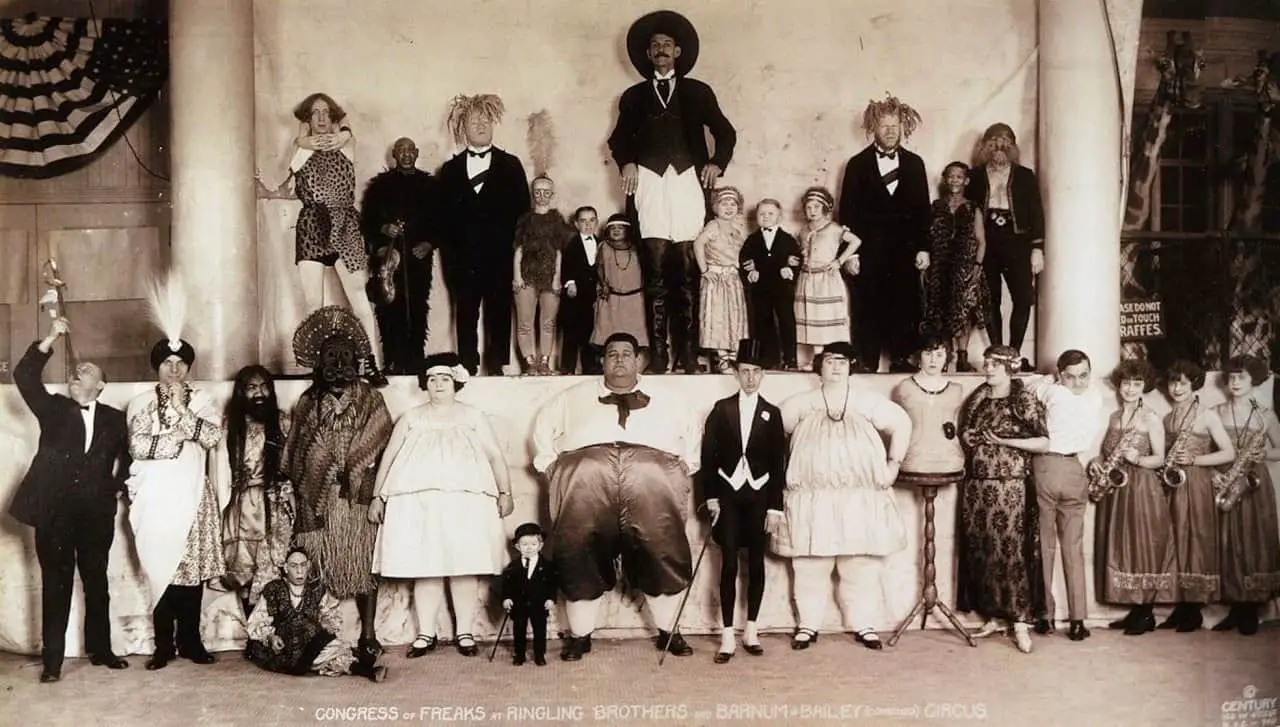

This house is haunted by a wife who Nebbercracker ‘rescued’ from the Freak Show (presumably so he could own her, though he seems wholly redeemed by the plot line). This woman was in the freak show because she was ‘the size of a house’ (very fat). I’m uncomfortable with this. In essence, the big reveal is that Nebbercracker is himself a victim, to a fat woman with PTSD from a lifetime of being held in a cage. Everything I could say on this has already been said, back in 2006:

As the house, Constance is therefore enormous, insatiable, crazed – just as she was in life. Mr. Nebbercracker, in contrast, is small and skinny, the one who placates her great rage. This portrayal of a fat woman as out of control with huge appetites (whether for food or for sex) – as, literally, a maneater – is unfortunately all too common. In fact, the very difference in size between a large wife and a smaller husband, whether in literature, film, or real life, communicates the message that she is the dominant partner. These stereotypes of fat women are particular to fat women – the reverse wouldn’t work. There are no cultural figures of fat men whose appetites must be controlled by their skinny wives.

Further, the house is only silenced when it is destroyed, at which point we see Constance’s ghost dancing with Nebbercracker before swirling off into the sky. Nebbercracker then breaks down in relief that he and Constance have finally been set free. Thus, it is only through Constance’s destruction that her appetite is forever controlled.

What’s wrong with this picture? Monster House doesn’t merely reinforce negative stereotypes – it depends upon them. There would be no plot if not for the purposefully grotesque figure of Constance.

Another film — not a children’s film — which uses the ‘big as a house woman’ as opponent is What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, from 1993.

Both films present images of the extremely fat woman as a hybridized “woman-house,” whose identity and body are merged with the physical structure of the house to which she is confined. Drawing upon the work of foundational psychoanalytic theorists, we illustrate that the fat woman as “woman-house” threatens those around her with psychic or physical annihilation and therefore must be destroyed.

As Big as a House: Representations of the Extremely Fat Woman and the Home by Caroline Narby & Katherine Phelps

Stories in which non-conforming women must die at the end extend beyond this narrow ‘women as houses’ trope. It is seen in a wide variety of films, including one of my favourites, Thelma and Louise.

Art didn’t invent oppressive gender roles, racial stereotyping or rape culture, but it reflects, polishes and sells them back to us every moment of our waking lives. We make art, and it simultaneously makes us. Shouldn’t it follow, then, that we can change ourselves by changing the art we make?

Lindy West

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE HOUSE IN GHOST STORIES

The book cover below is strongly suggestive of ghosts. What is it, exactly? The house. The gables. The vintage texture overlay, the aura in the sky, and also the fact that we can only see a part of the house. Dormer windows, and preferably attics, are almost a requirement, as are chimneys — hopefully one of those wide old chimneys — the kind you could send a kid down.

The haunted house is a character in its own right, ready to gobble up its inhabitants. One of the most famous haunted house stories was written by Shirley Jackson.

RELATED

Top 10 Terrible Houses In Fiction from The Guardian

PLAN

In a middle grade story where a group of kids must defeat something supernatural, they often visit some kind of sage. This is straight from mythic structure, a la Joseph Campbell. The screenwriters achieve a twist on this sage guy by making him the local video arcade loser.

BIG STRUGGLE

Every time I’ve watched this film I’ve gotten bored for the Battle sequence. I feel this is the film’s structural shortcoming (trumped only by its ideological ones). This is a story would would have benefited from a shorter screening time, but unfortunately the industry is set up so that feature films must be of traditional feature length. The big struggle sequence involves a house which literally comes to life and turns into an animated monster. Spectacle can only last so long before the audience zones out. I have always responded like this to elongated big struggle sequences, though I suspect fans of action movies appreciate them. Reviewers described the big struggle sequence like this:

But the overriding impression is assaultive to a progressively off-putting degree. Kenan keeps hammering away with stun-gun cuts, visual ammo suddenly flying in from out of frame and ear-splitting sound effects and music cues, to the point where at least part of the audience will want to tune out. In this respect, it is a theme-park ride, with shocks and jolts provided with reliable regularity. Across 90 minutes, however, the experience is desensitizing and dispiriting and far too insistent.

Though Jenny was useful for formulating the plans, it’s up to the boys to save the day with brute force:

While Chowder is driving a steamshovel, simultaneously battling the now-mobile house and leading it to a strategic point under a crane, DJ and Jenny are scaling the crane, DJ with explosives in hand that he will drop into the house’s chimney, blowing it apart. Jenny has a minor role in this – I can’t remember the exact sequence of events, but it’s something like, DJ stumbles and drops the dynamite, she grabs it, throws it to DJ, and he drops it in. It was all so predictable – and so unnecessary. Why couldn’t Jenny have dropped it in? Why are girls almost always accessories and rarely the heroes? Allowing Jenny to be the one to finally drop the dynamite would have made it a group effort, rather than a boys’ effort with a girl tagging along.

That Jenny doesn’t get to use the weaponry is the least of my issues. My issue is that Jenny doesn’t get a character arc.

The mainstream (adult) film equivalent of this is giving the female character the gun while the male characters use brute force with blunt objects and so on. Guns, in movies, at least, are seen as the easy way to win a fight. I am familiar with the ‘feminist equality’ argument for private and unmoderated gun ownership: “Guns level the playing field. A woman with a gun can fight a big man.” American homicide statistics don’t back this argument up, but I digress.

ANAGNORISIS

Ironically, the anagnorisis that DJ has is that after all that adult responsibility of saving the neighbourhood from the massive house woman, he would like to be a child for a little while longer. We realise this when he agrees to go trick or treating with Chowder.

Apart from this his friendship with Chowder has been reaffirmed. Previously, their child development was out of sync, but now these two buddies have overcome that.

NEW SITUATION

The house is destroyed. One lingering question: Where is Nebbercracker going to live? This is never answered, though Chowder speculates. Last thing we see is Bones climbing out of the rubble of the house. He has been trapped inside. He’ll probably assume he was on a drugged out bender.

In any case, the suburban neighborhood is now safe.

As for the romantic subplot, it’s kind of a rule that DJ ‘deserves’ to win Jenny. DJ is the more conventionally attractive boy and star of our story. Even J.K. Rowling herself has said that Harry should have ended up with Hermione. The problem with romantic subplots is that if the plot really is a distant second to the main action, we end up with a story in which the girl is given as a prize, with no real reason shown for why this girl would be interested in the boy she ends up with. For instance, a believable romance between equals features an ‘I understand you moment’, which is a phrase I’m borrowing from Matt Bird. I’ll just quote Matt:

The reason so many love stories fail, and so many lame love interests drag stories down, is that the writers have failed to add “I understand you” scenes.

“I understand you” moments don’t have anything to do with wanting to change the other person and everything to do with accepting: We don’t root for Beauty and the Beast to get together until the beast gives Belle his library.

Matt Bird, Secrets of Story

Matt does offer a bit of a disclaimer: Sometimes the writer can establish that two characters belong together before they even meet.

But why, exactly, are DJ and Jenny together? I can tell you why. It’s because DJ saw her across the road and it was love at first sight. In turn, Jenny is impressed by DJ’s saving the day while Jenny stood by and watched. I don’t know about you, but I think a smart, knowing character like Jenny would see right through that kind of bullshit. Don’t you? It’s how she was set up!

By the way, it was always clear that Chowder wasn’t going to ‘win the girl’. As explained by Michael Hauge, there are some rules of romantic triangles. (And by ‘triangle’ I mean the variety in which two boys are interested in one girl.)

1. Make the character who will be left behind a jerk who deserves to be jilted. This is the trick used here.Chowder is kind of lazy. The physical shortcut is that he’s also chubby, even though BMI and laziness do not correlate in real life. He says he worked really hard for his basketball, but he only asked his mom for a dollar 28 times. Not marriage material, in other words.

2. Let the rival be the one to realize the hero isn’t her destiny.

3. Give “Ms. Wrong” someone better to be with, who makes her happier than the hero can.

4. (Rare) Leave your protagonist alone at the end, but better off moving on.

The writers of Monster House have written a film that mostly works, structurally. They’ve relied on established, unhelpful tropes to that end.