Peter and the Wolf is a Russian fairytale for children, with musical composition by Sergei Prokofiev. This fairytale is much newer than most — it dates from 1936. This makes it far newer than the Grimm tales, which all predated the Grimm Brothers themselves — and newer than the fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen. This one is unusual of its type, because it was written with a specific educational purpose: to introduce children to various instruments of an orchestra.

The copyright history of Peter and the Wolf makes for an interesting and frustrating read. In the middle of the 20th century, schools (and anyone else) were free to use this story and music as they saw fit — either in remixes or as it is. Then in 2012 the American Supreme Court judged that previously copyright free works could, at a later date, become copyrighted. This battle had been going on for some time, at least since 1994.

None of this affected what Angela Carter did in her short story of the same name, regardless of what year she wrote it. Titles are not subject to copyright, and Carter’s is a completely different tale about a different Peter and a different kind of wolf altogether. The title encourages readers to consider that the Sergei Prokofiev story might have been different, but that’s where the analogy ends. The Wikipedia entry for the orchestral original offers a good summary of Prokofiev’s plot, for anyone interested in a closer comparison.

There’s also the 2009 short film which got in before the ruling, directed by Suzie Templeton, written for screen by Marianela Maldonado. In this version, the national enemies of the Russian original have been personified by a gang of street bullies. But the brutality of the duck murder is preserved, making for a story much darker than most Pixar-raised contemporary kids are used to. It disturbs my daughter no end, especially as the murder comes right after a slapstick scene which has a child audience giggling.

STORY STRUCTURE OF PETER AND THE WOLF BY ANGELA CARTER

SHORTCOMING

The clear main character of Angela Carter’s story remains Peter. She hasn’t switched the viewpoint over to the wolf, which would be another fine option for a re-visioning. She does switch our empathy, however — she does something more difficult. Carter helps us to share it between Peter and The Wolf. This is another excellent option for any re-visioning, because the message is always this: Everyone has their reasons for doing what they do.

The original Peter, being a child, has the usual child shortcomings: He is reliant upon his caregiver (the grandfather) to care for him. Angela Carter, who famously translated the Charles Perrault fairytales into English, was undoubtedly influenced by him, even though she used him as a negative example for how to depict women, in particular. Here she goes the Perrault route, and in writing this fairytale she begins a generation beforehand. In order to understand an individual, it was once thought, we must first know who their parents and grandparents were. We no longer think that, culturally. Or, if we do, we keep it on the down-low. We like to think — or to imagine — that we are not held hostage by our genetics and our ancestry. That anyone can become anyone else, so long as they work hard and be good.

Carter does actually start with the Wolf girl, which might trick you into thinking the girl is the main character. I’ve written before that it’s not always easy determining who the main character is in a story. I always come back to this: Who has the revelation at the end? In other words, who gets the character arc? That’s your main character. The Wolf girl is interesting, she is necessary, and big things happen to her in this story, but the revelation belongs clearly to Peter. She aids him in this. Carter’s Peter and the Wolf is technically an example of The Female Maturity Formula, and I point that out because yes, even feminist writers use it — my critique of this arc refers to the canon. Individual stories are absolved.

Peter is introduced in the fifth paragraph — quite a way down, considering this is a short story. Peter is revealed to be smart — good at deduction — but what is his shortcoming? If in doubt, look at the revelation. HIs shortcoming is that he has been taught to fear the wilderness, and anything that cannot be tamed. Carter tells us clearly:

When the eldest grandson, Peter, reached his seventh summer, he was old enough to go up the mountain with his father, as the men did every year, to let the goats feed on the young grass. There Peter sat in the new sunlight, plaiting the straw for baskets, until he saw the thing he had been taught most to fear advancing silently along the lea of an outcrop of rock.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

Fair enough, we should all be wary of wolves. Maybe. But as the story progresses, and we see Peter’s reaction to the rescue and abduction of the Wolf girl. Fear of life, and of nature in general, far outsizes reason. Guilt and fear paralyse him.

What Angela Carter does so well across all of her stories is link woman to nature. This isn’t Carter’s invention — she is drawing on a long, long history of misogyny, in which men are closer to God and women are closer to the Earth, and can never rise above. This is due to the unmistakable and harrowingly messy process of childbirth and reproductive cycles — cycles which were far more visible until the twentieth century. If women are close to earth, only men can be close to God, and only men can run the entire show. For more on that sorry history, which spans the last 3000 years at least, Marilyn French wrote a comprehensive history of misogyny in her book Beyond Power. Also a feminist, living in the same era as Marilyn French, Angela Carter critiques that same history — that women are to be considered abject because of our strong links to the Earth, and the cycle of life itself. She also makes the link between this view and organised religion, which in earlier times was inextricable from the rest of human thought.

DESIRE

Peter is a fairly passive character — the viewpoint character, in fact. With a character who looks on and observes events, you’ll need the strong, obvious Desire to come from someone else. In this case it’s clearly the Wolf girl, who is captured, but wants to break free from the humans. This desire is so ferocious that she creates a violent big struggle scene in the house.

Afterwards, Peter is left with a desire of his own, but this desire is far more subtle. Wolf girl’s desire is on the surface; Peter’s is under. He doesn’t know himself what he wants. He wants to assuage his generalised anxieties.

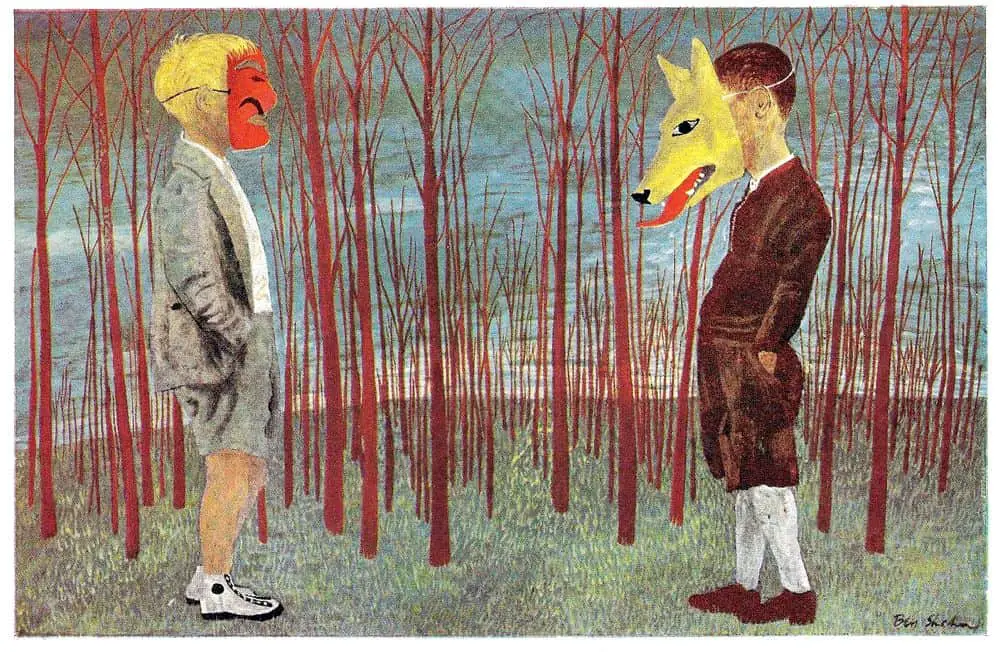

OPPONENT

The opponent is not the Wolf girl. Even in many orchestral versions, the Wolf and the Boy are pitted against each other, presented as equals at one point. In the 2009 short film, this is most clear when wolf and boy are each dangling from different ends of the same rope, eye to eye, each reliant upon the other for escape.

But it is enough to say that Peter is his own worst enemy? This never makes for a satisfying if that’s the only thing you’re doing, but it does work if there are other big struggles raging. You’re more likely to pull it off in a short story than in a novel, which can’t sustain that level of big struggle, unless it’s something like Fight Club, in which we are presented with a clear opponent, even if that opponent is revealed to be illusory.

Peter is his own opponent because he clings to a system of rituals which aren’t going to help him break free of his fears. You could say the church itself is his opponent, though it would be more accurate to say it’s the culture. Carter says ‘he had been taught’, passively, suggesting he’s learned this response from all sides. Again, church = culture, and culture = church in a setting such as this.

PLAN

Peter and Wolf girl are presented as diametric opposites — consider them different sides of the same personality, in the same way the Winnie the Pooh characters can be considered different aspects of a child’s traits and emotions. Wolf girl models one possibility — you can rage against the machine and take off to live your own life, literally in the wild, in her case. Or you can buckle down and be a good boy, doing everything expected of you and more.

Peter takes the latter route.

The boy became very pious, so much so that his family were startled and impressed.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

THE BIG STRUGGLE PHASE AND MISE-EN-ABYME

The battle scene in which the wolves come to rescue their girl is ‘a big struggle scene’ (better to call it a ‘fight scene’), but for plot purposes it is not The Battle Scene. This is a crucial distinction, and failure to see it can really muck up a story if you’re trying to write one. Peter’s Battle is far more quiet. The Wolf girl crouches before him, uninhibited by her nakedness.

It exercised an absolute fascination upon him.

Her lips opened up as she howled so that she offered hm, without her own intention or volition, a view of a set of Chinese boxes of whorled flesh that seemed to open one upon another into herself, drawing him into an inner, secret place in which destination perpetually receded before him, his first, devastating, vertiginous intimation of infinity.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

The word ‘devastating’ feels like it’s almost cull-able, but it’s not. This is Peter approaching his own kind of spiritual death. ‘Fascination’ is also important. Today, to be fascinated by something is a good thing — we’ve probably achieved a pleasant ‘flow state’. But that’s not where the word comes from, and in re-visioned fairytales, it pays to consider the medieval meanings of contemporary words. In the 1590s ‘to fascinate’ meant to bewitch or enchant. The word comes from Middle French, Latin and possibly from Greek as well. In any case, you didn’t want to be ‘fascinated’ by anybody in the 1500s, and you didn’t want to be accused of it, either, lest you end up burned for witchcraft.

An understanding of church teachings are necessary before understanding this story, and I think we all know it — sex is sinful. It still is, according to the major religions, outside marriage. Even in (most, I’ll not say ‘dominant’) secular culture, sex is unacceptable outside mutual consent. There’s something icky about the one-sided viewing — this is not consent, exactly. There is a single participant — subject vs object. But Carter inverts the gender of the usual victim in such one-sided experiences. It is Peter who remains affected by it.

The piousness itself is also a near death experience, but literally:

In Lent, he fasted to the bone. On Good Friday, he lashed himself.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

If you’d like to drive your point home, make like Angela Carter and include but a psychological AND a literal near death experience, rammed home by the actual death of a few characters close to the main one. (Mother figures and male best friends are common victims.)

MISE-EN-ABYME IN STORYTELLING

Using Angela Carter’s excellent example, I’d like to look into the mise-en-abyme technique which I’ve been noticing for a while in various stories. Only a writer such as Carter would take the vulva and vaginal opening and turn that into a mise-en-abyme metaphor; others have found different analogies.

What is mise-en-abyme, exactly?

I would describe myself as the kind of person who describes himself as the kind of person who would describe himself.

@Demetri Martin

- In Western art history, mise-en-abyme is a formal technique in which an image contains a smaller copy of itself, in a sequence appearing to recur infinitely; “recursive” is another term for this.

- In graphic art, it might be a painting of a painting, which has another painting inside itself.

- Stand in a dressing room lined with mirrors and watch the mise en abyme effect. Do you remember the first time you did this? Or maybe you don’t remember the first time, but still recall standing as a child between two mirrors and marvelling at the effect? Did this get you thinking about some pretty bizarre stuff, bigger than yourself? How there might be more than one of you, or how far the little versions of you might extend? Was it this that got you considering the concept of infinity, by any chance? It’s a powerful effect. It distances us from ourself. Which one are we? Are we all?

The song Green & Gold by Lianne La Havas is about that moment of being a little kid, looking in ‘the mirror whirl’ and wondering if it goes on and on forever. As an adult she looks back on her six year old self — she’s since had the revelation that ‘those eyes you gave to me’ let her see where she’s come from — her own heritage. Possible subtext: She sees she’s part of one long chain of peoples, stretching in both directions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnogG7IMj8o

When used in storytelling, mise-en-abyme is regularly linked to a ‘vertiginous’ sensation (quoting Carter directly), which in turn starts this spiral of questioning — the main character will probably see themselves as a very small part of something much larger. (Or they’ll remain blind to it, if you’re writing a tragedy. I wrote this kind of tragedy in our illustrated short story app, Midnight Feast.)

Mise-en-abyme and its link to Death

In No Go the Bogeyman, Marina Warner describes the macabre Medieval tradition of death art on church walls, and actual dead and decaying bodies within abbeys, as mise-en-abyme in nature. An example is The Hours of Simon Vostre, a text printed in Paris in the early sixteenth century. The text contains engraving of the danse macabre (Dance of Death) showing working women in various trades and working men. It was also customary for the spectre to wear a tatterdemalion (deliberately tattered) version of the costume of his prey and to imitate with grotesque exaggeration the victim’s usual activities. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyknBTm_YyM

What’s all this for?

To show that Death is a double; each of us has our own death in the mirror. Death is oneself on the other side, beyond reach. The macabre implicates us in mise-en-abyme, a hall of mirrors. And by means of its use of defamiliarization, it offers the capacity for self-examination. Many of the tombs in which the deceased was shown devoured by worms were actually commissioned and carved during the subject’s lifetime: thus, Archbishop Chichele, founder of All Souls, Oxford, may have contemplated the artistic progress of his own decomposing body not he tomb in Christ Church while he was still alive. These funerary monuments are designed not to engender memory in the narrow sense, nor prayer, but to provoke the pondering of self. It leads to the Anagnorisis phase of a story.

Mise-en-abyme in the Plot Structure

The story-within-a-story is a plot structure rather than a system of imagery, but might equally result in a mise-en-abyme effect for the reader. I’ve found good examples in children’s literature.

In Bye Bye Baby by Janet and Allan Ahlberg, the new mummy reads Baby a sad story with a happy ending, which describes the wrapper story itself. What if there’s another book within the book within the book?

Mise-en-abyme is sometimes used in comedy as a gag. SpongeBob and Patrick try to make money reselling chocolate bars but end up getting duped by a fish who first sells them bags for their chocolate bars, then sells them bags to carry their new bags. This is funny to us partly because the characters are stupid, but also partly because this could go on and on forever — hyperbole, in other words, without needing to go all the way. The SpongeBob example is also an example of character humour — most people can relate — we’ve all noticed that the more things we buy, the more things we need to buy for the bought things (new bookshelves for new books, a bigger garage for a new car). The purpose of this gag is the same as any other example of mise-en-abyme that I’ve seen: Its purpose is to get us to look inwards, stepping back, critiquing our own selves (and in this case, learning to laugh).

MISE EN ABYME AND PSYCHEDELICS

For reasons yet to be fully explored by science, a mise en abyme experience seems fairly common to those who take psychedelic drugs.

John Hayes, the psychotherapist, emerged [from a psychedelic experience] with “his sense of the concrete destabilised,” replaced by a conviction “that there’s a reality beneath the reality of ordinary perceptions. It informed my cosmology—that there is a world beyond this one”.

Another subject from Pollan’s book, Boothy, reminded me very much of Angela Carter’s description of the vulva:

This place in which I seem to find myself, already enormous, suddenly yawns open even further and the shapes that undulate before my eyes appear to explode with new and even more extravagant patterns. Over and over again I had the overwhelming sense of infinity being multiplied by another infinity. I joked to my wife as she drove me home that I felt as if I had been repeatedly sucked into the asshole of God.

Michael Pollan adds:

Boothby had what sounds very much like a classic mystical experience, though he may be the first in the long line of Western mystics to enter the divine realm through that particular aperture.

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan

Other Terminology

This terminology isn’t always used by storytelling experts when talking about the same thing. Some people talk in terms of ‘miniatures‘. But it is the same thing. By presenting the reader with the very large and the very small, you as writer are encouraging The Overview Effect. This will lead directly to a Anagnorisis pertinent to the story at hand. What writers need to decide: What is this character going to realise after their near death experience?

ANAGNORISIS

So, Angela Carter’s Peter is basically disturbed by the infinite mise-en-abyme effect of a girl’s vulva/vagina. He doubles down to prove himself a good boy, according to his culture and church. (His Plan.)

Where does this get him? Well, nowhere good. Angela Carter’s ideology regarding church conformity is foreshadowed by imagery:

[The wolves] left behind a riotous stench in the house, and white tracks of flour everywhere.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

‘Stench’, or any kind of smell, in a story generally, refers equally to an emotional state. ‘Black sticks of dead wood’ are a pretty obvious clue that Peter has been through some kind of spiritual death. The grandmother’s bitten hand ‘festers’. Infections fester, but we also use the word to refer to inner states which we can’t shake. Then, there is a death. Not Peter’s, but his grandmother’s. Note: Peter loses a female caregiver in a direct reflection — mise-en-abyme reflection — of the Wolf girl, who lost her female wolf caregiver.

Hopefully the reader is undergoing a revelation at this point: Peter and the Wolf girl are different sides of the same wild coin. There’s a bit of wild in all of us, and it cannot be tamed. Peter’s comes next. (Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak is a picture book with a very similar revelation phase… and therefore ‘theme‘.)

Rivers are often associated with revelations. This has a long history in the churches, and no doubt long, long before. Water literally makes a body clean, so the link between rivers and mental cleanliness is a natural one.

At the end of his first day’s travel, he reached a river that ran from the mountain into the valley. The nights were already chilly; he lit himself a fire, prayed, ate bread and cheese his mother had packed for him and slept as well as he could. In spite of his eagerness to plunge into the white world of penance and devotion that awaited him, he was anxious and troubled for reasons he could not explain to himself.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

Sometimes revelations happen while bathing in the river — less obvious is when they come after. The river does nothing for Peter. The ‘liquid’ is described as ‘cloudy’. No, he requires the wild Wolf girl to aid him in his embrace of his baser self — she is his (extreme) model for how to live a good life. So he sees her once more — this is some years later — and again we have the whole mise-en-abyme / reflection imagery going on, because that’s not finished until the Anagnorisis phase is finished. (Writing note: If you start a strong system of imagery, take it to its conclusion. Don’t abandon it partway.)

She could never have acknowledged that the reflection beneath her in the river was that of herself. She did not know she had a face; she had never known she had a face and so her face itself was the mirror of a different kind of consciousness than ours is, just as her nakedness without innocence or display, was that of our first parents, before the Fall.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

The Wolf girl is innocent to the extreme, animalistic degree — Peter watches her and realises that he, too, is innocent. By bearing witness to the violent episode of his youth, he has done nothing wrong, and needn’t spend the rest of his life paying penance.

Carter finishes off her system of imagery with this:

For now he knew there was nothing to be afraid of. / He experienced the vertigo of freedom.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

In this particular story, the mise-en-abyme effect = a glimpse into possible freedom.

Related and interesting: Carter’s Peter and the Wolf is basically a Being-toward-death revelation, seen often in young adult stories.

And if we still haven’t got it:

The birds woke up and sang.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

Carter is, of course, satirising fairytale conventions — she uses pathetic fallacy and bombastic onomatopoeia with intent. These birds are a form of pathetic fallacy — a technique in which the environment around a character emulates their own inner state. But it works. When the character arc is a bit under the surface, a bit unusual — when your theme and ideology isn’t the expected one, it’s not a bad idea to go the super obvious, slightly satirical route. Otherwise a huge chunk of readers won’t pick anything up at all.

NEW SITUATION

Angela Carter also finishes off in classic fairytale fashion, with a nudge towards the metafictive:

Then he determinedly set his face towards the town and tramped onwards, into a different story.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

As the Grimm brothers wrote, for instance, the narrator often likes to sign off by reminding the audience that this is a story, separate from the logic of real life. But the word ‘story’ is also used in contemporary English to refer to phases of real life, which is why I call it a tiny and subtle ‘nudge’. Carter does something clever with her final line:

‘If I look back again,’ he thought with a last gasp of superstitious terror, ‘I shall turn into a pillar of salt’.

Peter and the Wolf, Angela Carter

She thus avoids a big character arc, which readers have less time for: People do change after experiences, but a little at a time. Peter has entered the very initial stages of questioning certain ideas conveyed by the church, but there’s no way he’ll shuck it all off and become an actual Wolf man. He must find his own balance.