There’s a prevailing idea that we are all cohesive, single selves. Sure, we might change over time, but if there’s such a thing as ‘being yourself’ then we must accept our own absorption of the idea that ‘yourself’ (singular) exists in the first place.

For instance, a great number children’s stories contain the ideology that, whoever you are, it’s perfectly acceptable to be yourself.

Then you grow up and start to encounter creepier stories, the sort of story which suggests there IS NO TRUE SELF. We are all faking it. We’re all contain multitudes. This disarming idea suggests we can’t really trust other people… and worst of all, we can’t even trust ourselves.

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

Kurt Vonnegut

With Nietzsche, everything is mask. […] Nietzsche didn’t believe in the unity of a self and didn’t experience it. Subtle relations of power and of evaluation between different “selves” that conceal but also express other kinds of forces—forces of life, forces of thought—such is Nietzsche’s conception, his way of living. …His madness was his final mask. He had written: “And sometimes madness itself is the mask that hides a knowledge that is fatal and too sure.” In fact, it is not. Rather, it makes the moment when the masks, no longer shifting and communicating, merge into a death-like rigidity. Among the strongest moments of Nietzsche’s philosophy are the pages where he speaks of the need to be masked, of the virtue and the positivity of masks, of their ultimate importance.

Gilles Deleuze, Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life

Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else’s opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.

Oscar Wilde

THE OTHER SELF IN FICTION

So, which is it? Are you one or are you many?

The imaginary other is often seen in pop culture as a sign of craziness. But could an imaginary other self be really quite common? What if we include thought patterns such as:

- Imagining what you would like to say rather than what you really said

- Imagining yourself elsewhere to avoid an unpleasant or non-stimulating situation

- Imagining that you are different in the hope that one day you will be different, also known as ‘visualisation technique’ by certain self-help gurus

THE MEDIEVAL MIRROR CRAZE

In the twelfth century you’ve got what I call a ‘medieval mirror craze’ where they get obsessed by everything to do with the science and symbolism of mirrors. And this too contributes to a whole range of self-portraits in the twelfth century and afterwards.

A Cultural History Of The Self-Portrait, Books and Arts Daily podcast, interview with James Hall: The Portrait, a cultural history

Medieval thoughts about mirrors and their danger continued long after the medieval era ended. My paternal grandmother, born in the early 1900s, covered mirrors with tablecloths and towels whenever a lightning storm struck. She believed lightning reflected in a mirror could kill them all.

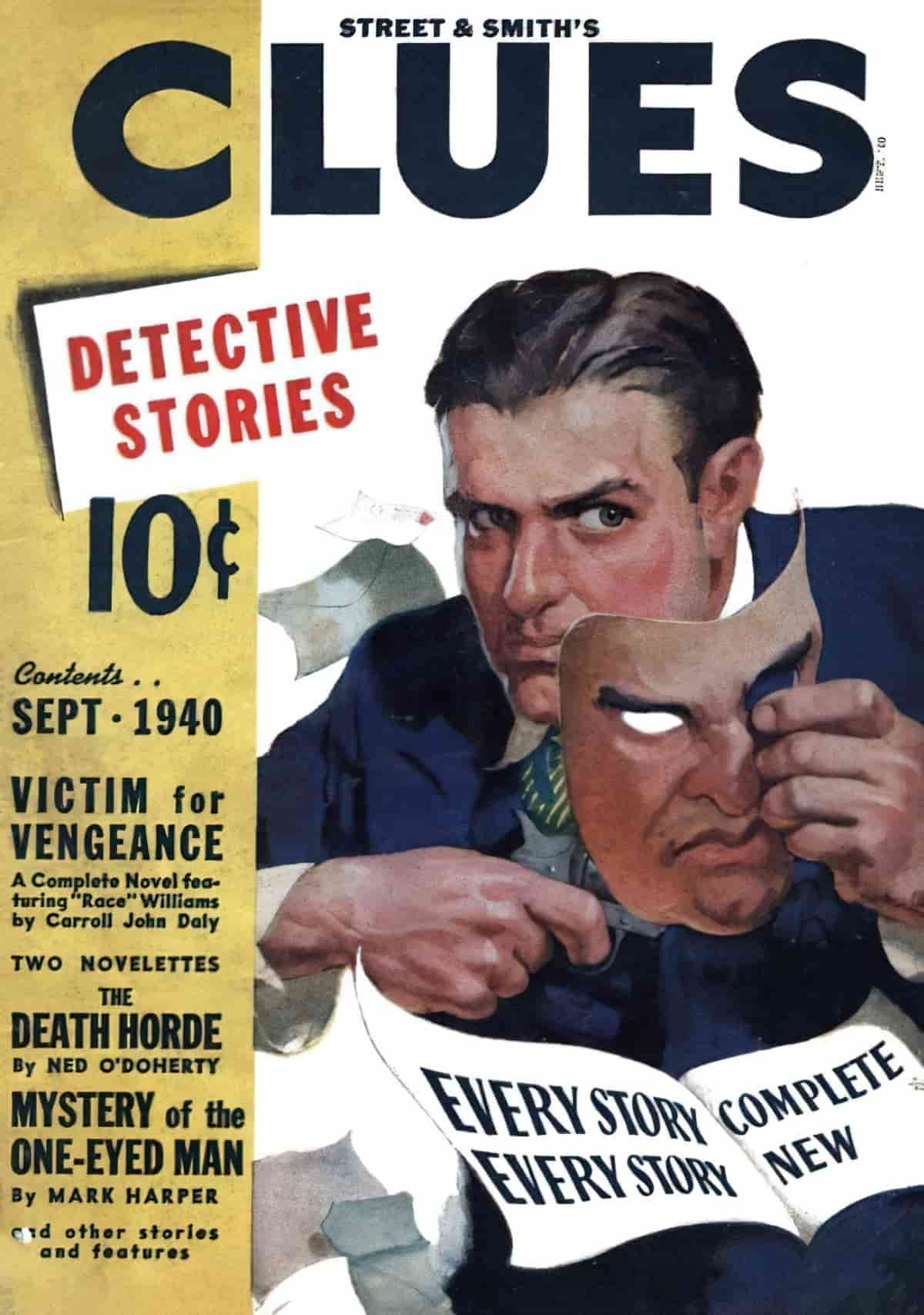

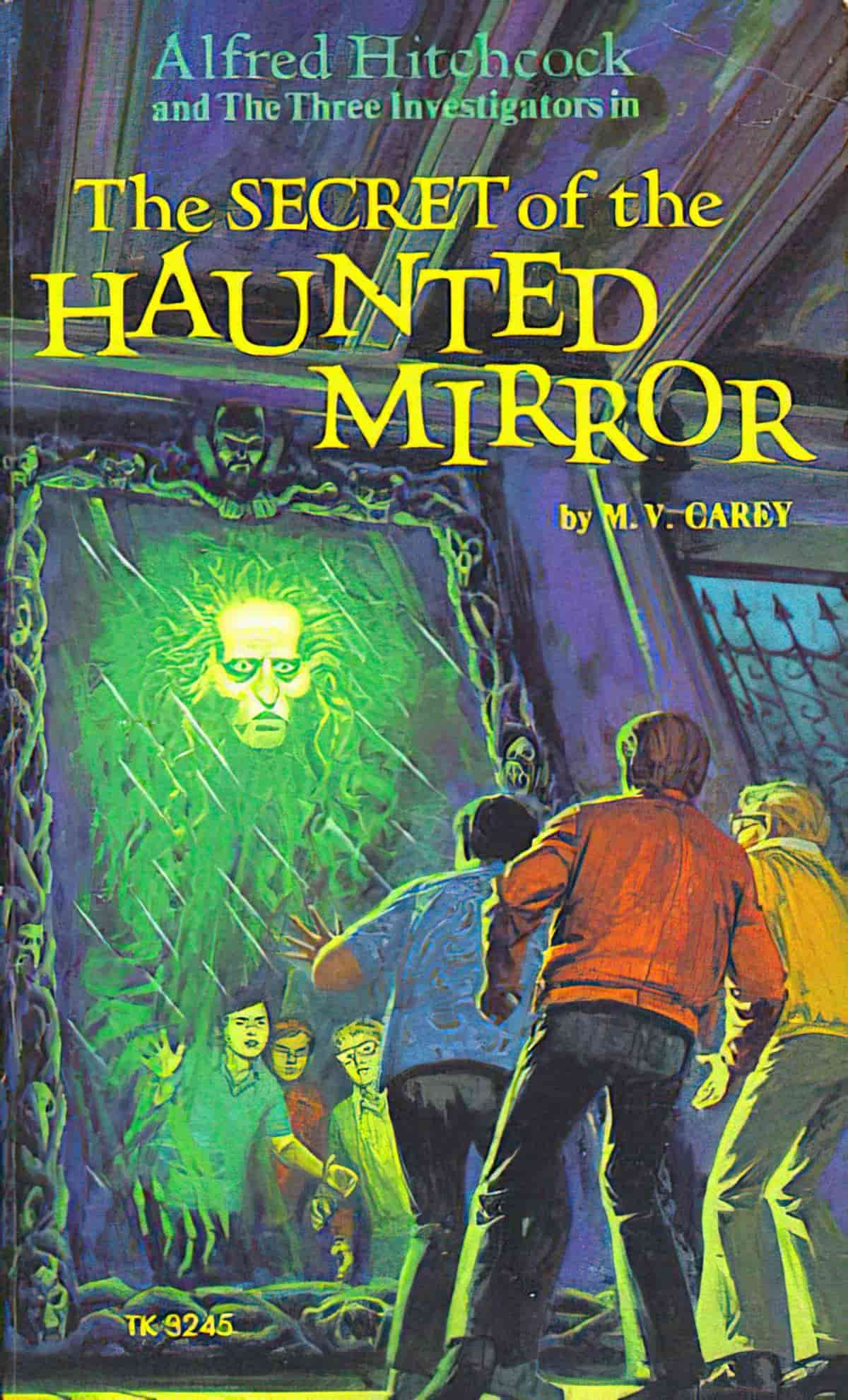

These superstitions about mirrors and their magic come in handy for writers of camp mysteries.

ROMANTICISM AND HIDEOUS OTHERS

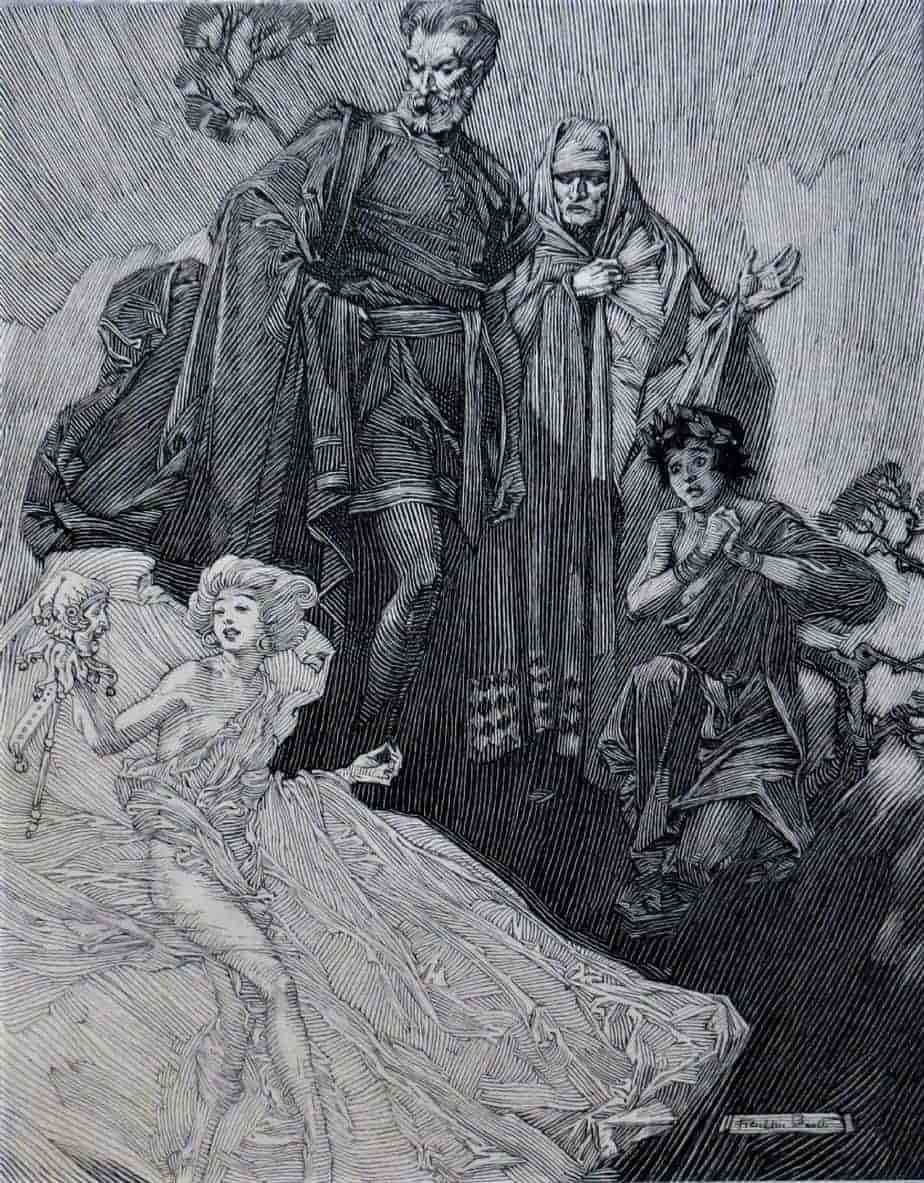

Romanticism gave us the notion, rampant throughout the nineteenth century and still with us in the twenty-first, of the dual nature of humanity, that in each of us, no matter how well made or socially groomed, a monstrous Other exists. The concept explains the fondness for doubles and self-contained Others in Victorian fiction: The Prince and the Pauper (1882), The Master of Ballantrae, The Picture of The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891), and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Significantly, these last two also involve hideous Others, the portrait of Dorian that reveals his corruption and decay while he himself remains beautiful, and the monstrous Mr Hyde, into whom the good doctor turns when he drinks the fateful elixir. What they share with Shelley’s monster is the implication that within each of us, no matter how civilized, lurk elements that we’d really prefer not to acknowledge—the exact opposite of The Hunchback of Notre Dame or “Beauty And The Beast,” where a hideous outer form hides the beauty of the inner person.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

Robert Louis Stevenson, in The Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) posed some interesting questions about the ‘divided self’. About a century later we got The Incredible Hulk on our TV screens. I was always creeped out by that — the sudden transformation from good guy into enraged beast. This view of the world suggests there’s a beast in all of us just below the surface, and we must expend effort to keep it reigned in.

This is also why Nick Lowe’s “The Beast In Me” makes an excellent soundtrack to The Sopranos.

And audiences haven’t grown tired of the idea, either. Too Clever Fox by Leigh Bardugo was published 2013. The cover art is a two-sided face (Janus) rather than a mirror, but the effort is the same.

Manichaeism

To be Manichean is to subscribe to the philosophy of Manichaeism, an old religion that breaks everything down into good or evil. … If you believe in the Manichean idea of dualism, you tend to look at things as having two sides that are opposed. In everyday English, we might say ‘a black and white’ view of the world.

A key belief in Manichaeism is that the powerful, though not omnipotent good power (God), was opposed by the eternal evil power (devil). Humanity, the world and the soul are the by-product of the battle between God’s proxy, Primal Man, and the devil.

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

The following are notes from Stuff To Blow Your Mind podcast Episode Through The Looking Glass:

- In the history of reflections in myth and story we have The Myth of Narcissus — a beautiful boy can’t stop gazing at himself in a mirror. He chooses to die in a pond rather than detach himself from his own image.

- Mirrors are a distorted reality. They are truth and illusion wound into one. Deep down we know that the image in the mirror is slightly uncanny — it’s us, but back to front.

- 13 Terrifying Fictional Mirrors (The Lasser glass, the Deiver glass, the fish in the mirror from Jorge Luis Borges’ The Book of Imaginary Beings, Alice’s looking glass, Prison of the Anti-God, the magic mirror from Snow White, The Mirror of Erised from Harry Potter, The Mirrors of Solomon Kane from the pulp tales of Robert E. Howard, the poem Enchanted Mirrors by Clark Ashton Smith, the mirrors of Thoth Amon in Conan the Destroyer, The Alien Reflection from Doctor Who, the mirror from the old Bloody Mary tale, and all the off-shoots, the mirror of Alex Holm from H.P. Lovecraft and Henry S. Whitehead’s 1932 short story “The Trap”.

- Mirrors as we know today came into being in the late middle ages but people weren’t so great at making glass back then. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that modern mirrors really hit the scene. Mirrors were basically for looking at ourselves.

- Around the 1660s scientists started realising mirrors could be used for telescopes.

- Mirrors can be used in therapy, too. In phantom limb syndrome and post-stroke paralysis mirrors can be used to help relieve the feeling of phantom limbs and, worse, actual pain. In some treatments, patients move ‘both’ limbs simultaneously and watch themselves in the mirror. This helps with the pain though there aren’t many studies on this. Brains don’t know how to process information when there is a conflict between what it sees and what it feels.

- You can always tell a two-way mirror by turning the light off. Once the light is off you can see who is on the other side, because two-way mirrors don’t have a coat of paint on the back of them. (Why is this not used more often in TV shows?)

- People in a room with a mirror are less likely to judge others based on social stereotypes. When people are made to be self-aware they’re more likely to stop and think about what they’re doing. Ergo, mirrors make us more self-aware.

- In stories mirrors are often used to show the truth that cannot be seen otherwise.

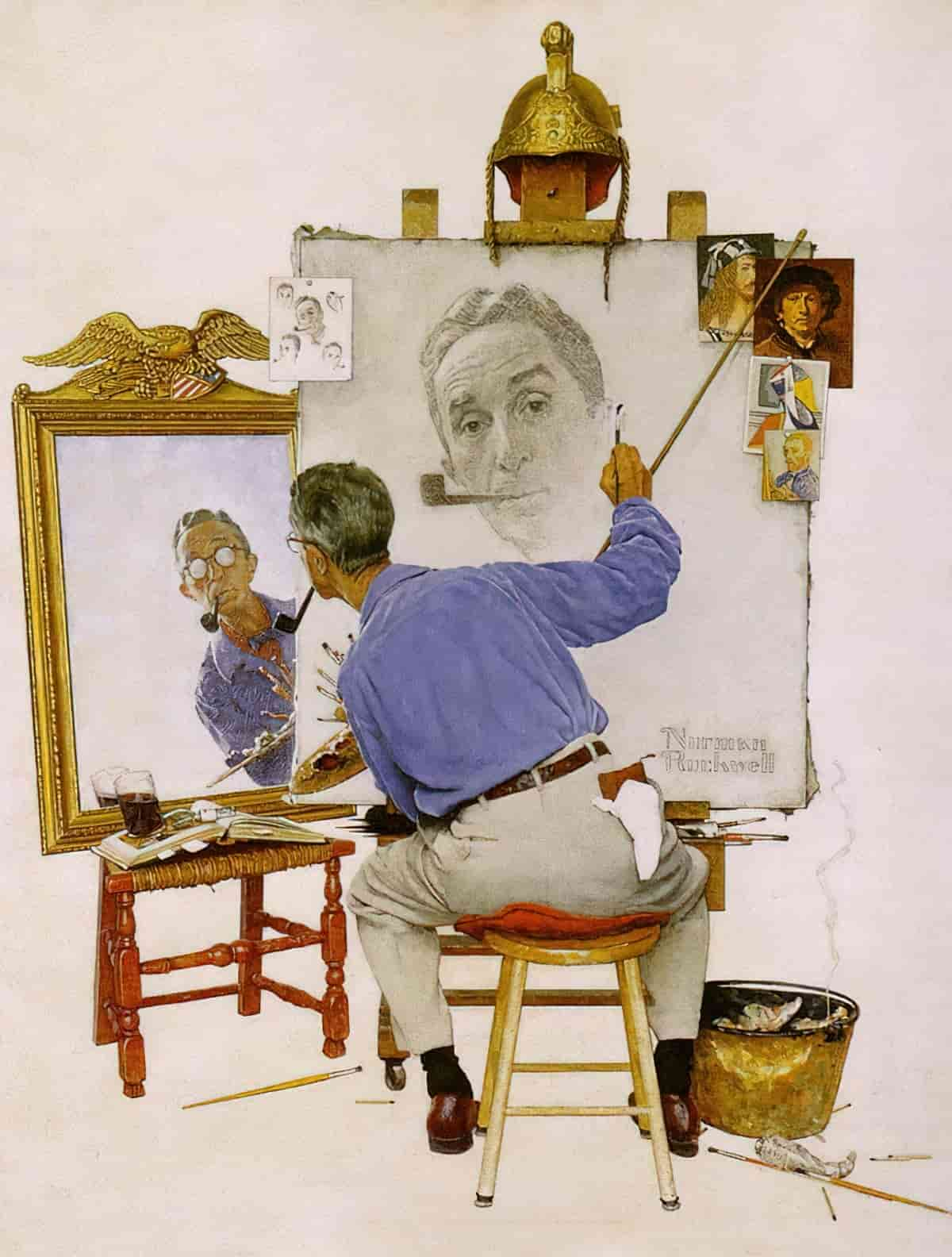

- The Venus Effect describes that feeling you get on trains where you’re looking into the reflection on the glass and actually you’re looking at someone else, or you realise someone is looking at you. It comes from a famous painting. There are a number of paintings in which the character in the painting is actually looking at the viewer. Norman Rockwell is another one, and he gets it right.

In movies The Venus Effect is used a lot, and images often don’t match up with optical reality — to avoid having camera staff etc. in the picture. Yet we hardly ever notice. We don’t have a good grasp on ocular reality and gloss over their uncanny nature.

Most people can’t answer correctly the size of someone’s own face in the mirror. We tend to think our face in the mirror is the same size of our faces. Faces in the mirror are always exactly half the size of the real face, because the mirror is exactly halfway between the person and the reflected image.

Mirror agnosia is a condition in which patients lose a sense of reflection, usually after a stroke or brain injury. Patients can’t figure out their bodies in time and space. (We need this skill when driving, parking, backing etc.) Other patients have no trouble recognising other people but can’t recognise their own faces in the mirror.

Tim’s Vermeer (2013) is a documentary directed by the magician Teller about a painter who could depict such photorealistic paintings before cameras existed. The answer is that he used mirrors.

RELATED

Anamorphic sculptures reveal their secret shapes in the mirror from io9. These sculptures have a creepiness about them which derives, I think, from this fear that what we see in the mirror does not actually reflect reality. To extend the fear, what if nothing is as it seems?