**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Miles City, Montana” is a short story by Alice Munro, and first appeared in the January 14, 1985 edition of The New Yorker. The story was subsequently published in Munro’s 1986 collection, The Progress of Love.

The setting is a small town near a little nameless river that flows into the Saugeen, in southern Ontario.

There are hints of the Babysitter Urban Legend in this one, appealing to the fears of adults who entrust their children to irresponsible young women who are more interested in kissing their boyfriends than in keeping watch over their precious charges.

I just want to get this out of the way: Who eats peanut-butter-and-marmalade sandwiches? Is that a thing?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What do you remember about being six years old? Do you have any memories which you now suspect aren’t memories at all, but inventions based on oft-recounted stories?

- How would you describe the friendships/playmates you had at age six? What games did you play together? Who decided them? Who was in charge, and who followed?

- In this story, the narrator remembers being six because a terrible thing happened: Her playmate drowned in the river. At the funeral, she is required to wear itchy white stockings, which bleed into a wider feeling of disgust, aimed specifically at her parents. When you recalled being six, how did the memory make you feel? Was this feeling inspired/provoked by something specific in the environment?

- Can you think of a quotidian day in which you feel you almost died? Perhaps you almost had a traffic accident, or almost fell from a high ledge, almost got electrocuted… What did you make of the reality that you survived? What did you tell yourself about that?

- What do you make of the narrator’s marriage to her husband Andrew? How would you describe the dynamics?

- What does the narrator understand about herself now that she didn’t understand when she was in her mid twenties, on the road trip?

- Before the personal tragedy, the characters sing in the car: Five little ducks went out one day/Over the hills and far away./Once little duck went/”Quack-quack-quack.”/Four little ducks came swimming back. In stories, children’s songs, rhymes and games are frequently utilised to presage a horrific turn of events. This one, in hindsight, foreshadows water and disappearance. Can you think of examples from other stories (books, TV or film) which utilise the innocent world of children to horrific effect?

- Opening with a tragic drowning, the narrator keeps circling back to tragedy and water. Where else does she mention water linked to death?

- How would you describe the general shape of this story?

- This story is full of juxtapositions, at the macro and micro level. At the macro, is the juxtaposition between an actual death in the wrapper story and a near death in the wrapped. What else does Alice Munro juxtapose, and to what end?

WHAT HAPPENS IN “MILES CITY, MONTANA”

A highly introspective first person narrator, never named, looks back on her childhood, cut in two by the awful 1941 event of a child drowning. The funeral had been held at her house. She remembers feeling disgusted by the adults who gathered there. Also angry, and uncomfortable due to itching stockings.

Twenty years later, in 1961, the 26-year-old narrator embarks on a road trip with her husband and two children East across the USA from their home in Vancouver to Ontario, where they are from. They’re driving a new car with a ‘lively, sporty’ image to replace their old 1951 Austin.

This narrator is highly retrospective, an entirely different person from the younger version of herself she describes. She understands many more things after the wisdom of hindsight, for example that she had a very binary view of the personalities of her daughters, one lightly complected, the other dark.

When the family of four reach Miles City, Montana, they come across a swimming pool. It is closed for a few hours, but the woman in charge lets the children swim while the narrator and her husband stay in the car. Eventually she starts to wonder if her children are okay.

She sees the older daughter, Cynthia, and asks where Meg is. Cynthia tells her mother that Meg has disappeared; the narrator screams; the husband comes running, then pulls Meg out of the water. She hadn’t drowned.

Meg had reached for a comb in the deep end and fallen in. Her body made such a light splash that nobody heard. The writer reflects on how differently her life would have played out had Meg drowned that day. She recalls Steve Gauley’s funeral.

Now she understands the demeanour of the adults at his funeral, twenty years earlier when she was disgusted by them.

The family continue on their road trip, with their daughters wholly trusting that their parents will take good care of them. They also trust themselves to be forgiven for their mistakes.

CHARACTERS IN “MILES CITY, MONTANA”

THE NARRATOR

This story lingers on three different periods of the main character’s life: Childhood, twenty years later when she was a young mother, and again into the 1980s, when she is now a divorced older woman.

She was six years old when Steve Gauley drowned. She has clear (but probably false) memories of her father bringing his body from the water into town.

Partly because these two were sort-of friends, and because the narrator came from a Good Home, the funeral was held at her house. The living room was large enough, her mother sufficiently organised.

In retelling this story, the narrator can’t say for sure which memories reflect reality, and which have been invented due to stories retold, and a child’s imagination. This is an accurate depiction of how memories work around the age of six.

It gets more complicated than that. This is the first time the narrator feels disgust for her parents:

Children sometimes have an access of disgust concerning adults. The size, the lumpy shapes, the bloated power. The breath, the coarseness, the hairiness, the horrid secretions.

Alice Munro

Disgust of older bodies doesn’t stop in early childhood. Much middle grade gross-out humour relies on jokes about disgusting adult bodies. (See Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid, e.g. a pool scene in Dog Days.) I believe it continues into middle age, applied to any body older than our own. In an excellent takedown of the awful, fatphobic film The Whale, feminist philosopher Kate Manne writes, “I get the sense that most middle-aged people could tell Ellie a thing or two about our own bodies that would shock and appal her.”

Here, the feeling of disgust seems tied to the itchiness of the compulsory white stockings

STEVE GAULEY

The narrator’s childhood friend who in 1941, at the age of eight, drowned in the local river. He has no mother, brought up by a semi-competent father. People around the neighbourhood would see him buying “sensible” food like pancake mix and macaroni at the local store.

The narrator knew him “fairly well”, but mainly as an irritating, competitive sort of child (nothing atypical of the age).

In their childhood play, the narrator and Steve “were riders and horses both”. This mirrors the expansive play engaged in by the main characters of another Alice Munro short story, “Spaceships Have Landed“.

MR GAULEY

Steve Gauley’s father.

His father was a hired man, a drinker but not a drunk, an erratic man without being entertaining, not friendly but not exactly a troublemaker. His fatherhood seemed accidental, and the fact that the child had been left with him when the mother went away, and that they continued living together, seemed accidental.

Miles City, Montana

In fiction, a character’s house mirrors (or ironically subverts) the inhabitants, and so it is here, unironic. She uses a grammatical pattern X but not Y:

They lived in a steep-roofed, gray-shingled hillbilly sort of house that was just a bit better than a shack—the father fixed the roof and put supports under the porch, just enough and just in time—and their life was held together in a similar manner; that is, just well enough to keep the Children’s Aid at bay.

Miles City, Montana

And further down, Munro repeats the same sentence structure to describe the son at school: He was solitary, though not tormented. A positive followed by negation, subverting (or pre-empting) incorrect conclusion on our part. Readers are taught not to pre-judge this child.

Twenty years later, when the narrator’s young daughter is trying out a new word, that new word is ‘image’. Image, appearance, surface…

ANDREW

The narrator’s husband. Whereas the narrator comes from a working class (turkey farm) background, Andrew comes from a middle class home with all the attendant social pressures. The narrator doesn’t feel at home in the company of his family, always preferring to be back on the turkey farm.

The narrator has ambivalent feelings for her husband, especially since he has told her in the past: “I know that I’d be better off without you” and also “You’d be happier without me.”

This guy really is a pain in the neck, though he’s not unusual for a man of his era when it comes to sandwich demands on his wife. Stopping for a picnic, he complains the sandwiches don’t contain lettuce:

“They’re a lot better with lettuce.”

“I didn’t think it made that much difference. Don’t be mad.”

“I’m not mad. I like lettuce on sandwiches.”

“I just didn’t think it mattered that much.”

“How would it be if I didn’t bother to fill up the gas tank?”

“That’s not the same thing.”

Miles City, Montana

(Before pacifying him with an apology) the narrator has pointed out Andrew’s ridiculous false equivalence, and because this is an Alice Munro short story, I am on alert for other, symbolic, metaphorical examples of false equivalence. Munro has already alerted me to themes of image versus appearance.

CYNTHIA

At the time of the road trip, Cynthia is six years old. Light hair, pale skin. Intelligent.

Again we have a warning from the narrator that we should not be taken in by appearance:

It seems to me now that we invented characters for our children. We had them firmly set to play their parts. Cynthia was bright and diligent, sensitive, courteous, watchful.

Miles City, Montana

MEG

At the time of the road trip, Meg is three and a half. Darker hair, darker skin, less outgoing than her big sister Cynthia.

The narrator understands, from this reflective distance, that she thought of her daughters in terms of a light and dark binary:

Not rebellious but stubborn sometimes, mysterious. Her silences seemed to us to show her strength of character, and her negatives were taken as signs of an imperturbable independence.

Miles City, Montana

THE SHAPE OF THE STORY

I wonder if first person retrospective narratives — especially obsessive ones — might naturally follow a vortex. It’s how I’ve found lyric memoir to work; maybe it’s true of fictive versions of retrospection, too. A preoccupied (haunted?) narrator turns around and around in her hands the most potent moments of her past, gazing at repeating patterns and shapes as she spins. I see this happening — almost literally see a narrator turning a magic spindle in her hands — in Kincaid’s Mr. Potter.

Jane Alison, Spiral, Meander, Explode

This family is on a road trip: linear. Road trips are an American spin on the Odyssean mythic journey.

But while on this trip, there’s no outside Minotaur opponent bearing down on the family, threatening harm, bringing them close together or breaking them apart. The monster comes from within. This narrator is nothing if not haunted, and when she circles back to tragedy, and the awful blots on her memory of past times, the story becomes a spiral.

The flood at the turkey farm, with memories of pulling heavy, wet bodies out of the water, is a clear example of foreshadowing, but it’s doing double duty, showing how the narrator can’t move past these thought spirals. She even says on the page that she (and her husband) can’t let things go. They have long memories, and are inclined to ‘take umbrage’.

Closer to the event, the narrator spots a water fountain, but approaches it ‘in a roundabout way’.

I had to look up Roto-Rooter, on the side of the lifeguard’s boyfriend’s truck:

Roto-Rooter liquifies stubborn grease and soap, allowing hair to become exposed and weakened. Then Roto-Rooter attacks the hair, quickly breaking apart the blockage and weakening its hold. Finally, powerful surfactants go to work, dissolving clog remnants and flushing them away.

In a story about the drowning and near-drowning of a child, the imagery evoked by this tool is horrifying. Sure enough, when I looked up some pictures of this contraption, it involves water, spinning and sucking-in.

Another name for spiral is of course whirlpool, which is particularly apt in a story about children drowning. The water seems to come alive, sucking them in. The (metaphorical) whirlpool is the monster, and this narrator cannot break free of it. The very plot itself is structured as a whirlpool.

THE SELF-REVELATION

The narrator circles back to the beginning of the story, disgusted by her parents at Steve Gauley’s funeral, little Steve, who really did drown. Now she has children of her own, she has come to understand something of her parents’ grief that day. By hosting the funeral, they appeared to have ‘given consent’ to Steve’s death.

Of course, appearance is far different from what’s going on in someone’s head. They appeared calm and collected that day, but they would have been imagining, what if it were our child?

She is left feeling insecure about the stochasticity of life—the luck of it all—and how if one single thing had gone differently, her daughter would have drowned.

In the bookend story of Steve Gauley, she realised her parents could not protect her, not really. In the bookended story she realises all the ways children can die, and how she, as a parent, cannot protect them either.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

“AQUIFER”

Australia’s Tim Winton has also written about a man looking back on a drowning that cut his childhood in two but, unlike in Munro’s story, the child who drowned had bullied him, and the narrator had watched the drowning happen without intervening or calling for help. (See “Aquifer” in The Turning.) As in this story, the narrator’s memory of the drowned child comprise bullying incidents, though the boy in “Aquifer” seems more malicious. When a child you don’t even like dies, this complicates feelings. They are not black and white.

STAND BY ME

Stand by Me (based on a Stephen King short story) is also the tale of a grown man who revisits his childhood home town, punctuated by the death of a boy about their age.

SHORT STORIES BY STUART DYBEK

Another short story writer who structures his plots to support his themes (also a New Yorker writer) is Stuart Dybek. See, for example, “Pet Milk” (1984) and “We Didn’t” (1994).

JUNEBUG

If you enjoyed this story, I recommend the film Junebug. The 2005 Junebug is like the film adaptation of an Alice Munro short story. (It’s not. And I mean that as the highest praise.) I won’t tell you any more lest I ruin it, but it’s set in the American south, not in Canada.

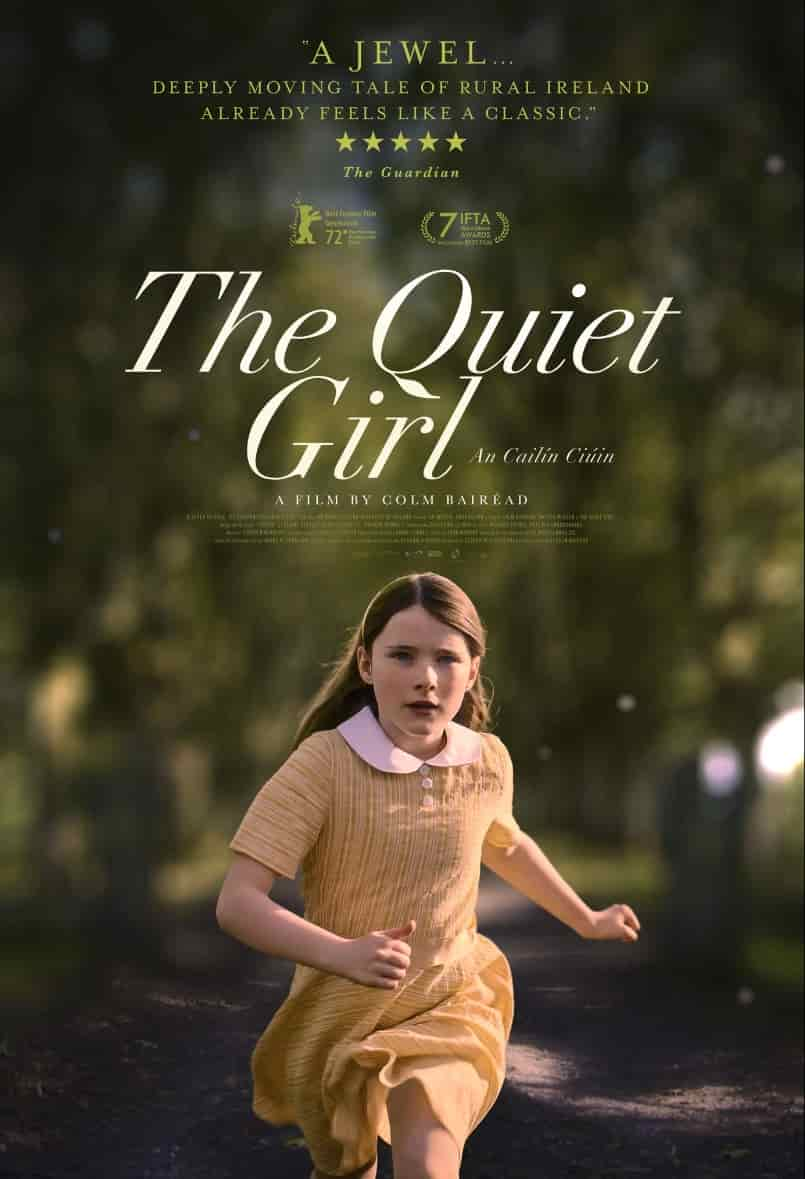

THE QUIET GIRL

The Quiet Girl, set in 1981, is a 2022 Irish film which has some big crossovers with Alice Munro’s “Miles City, Montana”: a near drowning prefigured by an actual drowning which happened before the story begins; a road trip; a family falling apart.

Rural Ireland 1981. A quiet, neglected girl is sent away from her dysfunctional family to live with foster parents for the summer. She blossoms in their care, but in this house where there are meant to be no secrets, she discovers one.

THE PROGRESS OF LOVE (1986)

- “The Progress of Love” in the October 7, 1985 edition of The New Yorker

- “Lichen” in the July 15, 1985 edition of The New Yorker

- “Monsieur les Deux Chapeaux“

- “Miles City, Montana” in the January 14, 1985 edition of The New Yorker

- “Fits“

- “The Moon in the Orange Street Skating Rink” in the March 31, 1986 edition of The New Yorker

- “Jesse and Meribeth“

- “Eskimo“

- “Queer Streak“

- “Circle of Prayer“

- “White Dump” in the July 28, 1986 edition of The New Yorker