Wolf Hollow (2016) is a middle grade novel by Lauren Wolk. This mid-20th century story is chock-full of symbolism which makes it great for a novel study. Here I focus instead on the writing techniques, for writers of middle grade.

Though moons tend to be massive in children’s books, the moon on this cover would have to be the most massive I’ve seen in a while!

I have previously taken a close look at a lesser-known picturebook called Wolf Comes To Town. Wolf Hollow is the literary, middle-grade version of that book in some ways.

Word count of Wolf Hollow is 60,000. Originally written as an adult book, marketed and edited as a children’s book.

SETTING

West Pennsylvania, 1943, autumn. We’re told the year right away. It’s immediately clear that this is a war-aftermath story.

SNAIL UNDER THE LEAF

“Wolf Hollow” is a romantic, intriguing name reminiscent of something Anne Shirley would dream up. (Raccoon Creek and the Turtle Stone are other fetching names used in the book.) But unlike the world of (the original) Green Gables, this is no utopia. Instead, Wolf Hollow is an ‘snail under the leaf setting’, where people grow ‘victory gardens‘ and residents are surrounded by nature. There is plenty of hygge — the peeling of apples, the large family table in their big, warm farm house.

By the time we got to the schoolhouse, it was raining in earnest. We three had worn oilcloth ponchos, hoods up, and boots, so we were plenty dry and warm, but many of the other children came in soaked and shivering.

SEASON

Like many stories with girl main characters, this story is closely connected to the seasons. Notice how the hygge is moderated by details that show this setting is not in fact utopian:

Each season meant a world refashioned inside its stalls and storerooms.

Pockets of warmth in winter, the milk cows and draft horses like furnaces, their heat banked by straw bedding and new manure.

In spring, swallows fledged from muddy nests wedged in crannies overhead, and kittens fresh and soft staggered between hooves and attacked the tails of tackle hanging from stable pegs.

Come summer, yellow jackets nested in the straw, old oats sprouted through the floorboards, Houdine hens laid eggs in odd places where they might yield chicks, and dusty sunlight striped the air like bridges to somewhere else.

TECHNOLOGY

This family has had electricity for a few years, introduced under President Roosevelt. Electricity had already become common in American homes during the 1930s but took longer to reach rural areas. This is one of the things which would’ve set a divide between ‘country kids’ and ‘city kids’ (Betty).

SCHOOL

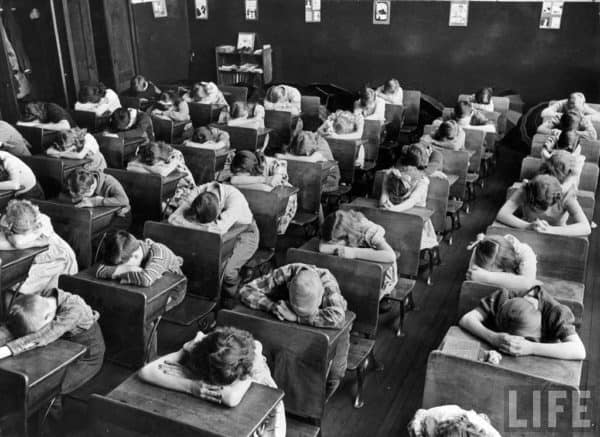

Annabelle’s class would have looked something like as depicted above, but because of lack of resources the classroom is overcrowded, so that when everyone turns up most students have to share a seat.

Today, I would learn some arithmetic, no doubt, and a few state capitals, why we fought the wars we fought, what Anne of Green Gables would get up to next, and why I shouldn’t mix bleach with ammonia.

WAR

The futility, or the insignificance of war to these country children, is shown in the sentence above. War is listed in the same sentence as far more mundane things, including cosy fiction. The children don’t see the point of war.

FEMINISM

Annabelle realises she must do well at school. With two brothers she won’t have the opportunity to run the family farm. She has been told to study hard and get a career. Other girls of that era would have been told to marry well, but expectations were changing rapidly for women both during and after the war.

STORY STRUCTURE OF WOLF HOLLOW

SHORTCOMING

Annabelle is a likeable, ordinary girl. Her shortcoming is that so far she has led a happy, sheltered life with no real calamity. At the magical (critical) age of 12 this is about to change.

Her happy, sheltered life exposes her shortcoming — she doesn’t yet know how to cope with adversity. Over the course of this story she must learn.

DESIRE

Overall, Annabelle wants to be left in peace to go to school and get a career.

In this particular story, Annabelle wants to stop Betty from bullying her and to keep her brothers safe. Later, this morphs into the intense desire for justice — to protect Toby.

OPPONENT

Betty

Betty is introduced on page 5. As newcomer, she is immediately interesting to both Annabelle and to the reader. We expect things of newcomers. She is a big, tough 14 year old girl from ‘the city’. She’ll be living with her grandparents, the Glengarrys.

Betty is a bit of a stock bully. But when she kills the bird (the inverse of Save The Cat) it becomes clear that she is more sociopathic than your typical middle grade bully. This girl has real issues. Partly to avoid problematic stereotypes, perhaps, Betty is blonde. (In the First Golden Age Of Children’s Literature you rarely met a blonde baddie.)

That said, Betty’s pretty blondness is partly what leads to her getting away with baldfaced lies. Her grandparents don’t believe she is violent and the adults don’t think to question if she really could see Toby on the hill from the belfry. The way adults discriminate based on complexion and pigmentation is brought to the fore when Annabelle asks her father who Hitler does like:

My father thought about his answer. “People with blonde hair and blue eyes,” he said.

“I would assign every lie a color: yellow when they were innocent, pale blue when they sailed over you like the sky, red because I knew they drew blood. And then there was the black lie. That’s the worst of all. A black lie was when I told you the truth. ”

Steve Martin

In this way, Betty is the local little Hitler. Like Swallows and Amazons, also set across war time, here we have a novel where the community big struggles fought by the children in some ways mirror what’s going on in the wider world. Similarly, Betty has targeted Annabelle because she perceives she is rich. One part of the reason for anti-semitism — irrational as it is — has historically been due to the perception that Jewish people accumulate an unfair amount of wealth owing to their sticking together and supporting each others’ businesses.

One sure sign that someone is an anti-Semite is if he agrees with the statement that “Jews have too much power in our country today.

Mark Weber

Annabelle is not Jewish, though she does have brown hair and brown eyes. (A ‘Betty and Veronica’ dichotomy.) She comes from a WASPish family.

Wolk makes clear exactly where Annabelle’s family sit in the economic hierarchy: as farmers they are neither poor nor rich, but exist outside the urban definition of ‘rich’ or ‘poor’. There is little to spare and the house is Spartan but being an old family with a large farm, they have been able to donate land for the school and church and are therefore rich by many standards.

However, the idea that you can look at someone from the outside and assume things about them is the critical idea here; Annabelle is not rich.

Andy

As Betty’s love interest, Andy is the romantic opponent. Andy, like Betty, is often compared to a dog. When he turns up late for school one rainy day he ‘tipped off his hood and shook all over like a dog as he looked around the schoolhouse.’

Aunt Lily

Annabelle’s parents are excellent parents, in danger of being Mary Sue characters, actually, so to disrupt the harmony at home we have Aunt Lily, another stock character who reminds me of two other fictional characters: Aunt Beryl from Katherine Mansfield’s most famous short stories, and from children’s literature, of Kate DiCamillo’s Eugenia from the Mercy the Pig series.

Aunt Lily is severe like Eugenia but also has a dreamy, romantic, thwarted-desire side to her, depicted with the small but telling detail that Aunt Lily goes to her room for Bible study, but can also be found listening to music and dancing at the end of her bed.

(Interestingly, Aunt Lily is a postmistress, which is the job L.M. Montgomery had, author of Anne of Green Gables. I wonder how closely L.M. Montgomery herself conformed to the severe postmistress trope.)

John and Sarah

Annabelle’s parents are loving and warm. Their response to the bullying situation is quite modern, in fact. An attitude fairly common in earlier eras was that children need to look after themselves, fighting back against bullies to learn fortitude. Not so in this situation — when Annabelle tells her parents what’s been going on with Betty they tell her they’ll take care of it and that she should have told them sooner.

But the parents — owing to their goodness — are also opponents, in a way, because in any healthy parent-child relationship, the parents will never be completely on your side. Annabelle doesn’t want to worry them with her Betty issues so she hides the problems she is having. And here’s a storytelling problem — perhaps a problem for the modern child — “Why doesn’t Annabelle simply tell an adult immediately?” ‘Tattle-tales’ and ‘dirty dobbing’ were common insults when I went to primary school in the 80s, but in the last 10-20 years schools have largely instituted zero tolerance for physical violence and I like to think that most children would tell an adult if they were left with a black welt. Wolk explains in several different places why Annabelle won’t tell her parents. First it’s because she’d like to deal with her own problems on her own — which is actually a rule for main characters in children’s literature:

I wanted to see if she was a barker or a biter.

At the beginning of chapter four:

My mother gave me a funny look as I stood at the back door the next morning, readying myself, before setting off for school. When she said, “Something wrong, Annabelle?” I nearly told her about Betty. It wold have been a relief to put the whole thing in her hands.

But although there were only apples and potatoes, beets and a few winter squash left to bring in, and although she, of all women on earth, was capable and strong, I had it in mind to spare her this particular big struggle. I’d thought it through: If i told her, she’d have to go to her friends, the Glengarrys, and tell them that their granddaughter was a hooligan, something they surely already knew but would not want to hear from a neighbour.

And despite the fact that she’d been able to fix nearly every broken thing in our lives, my mother could not promise me that Betty would not come at me again, even angrier — or worse, go after my brothers — if I tattled on her.

I had learned what incorrigible meant. A scolding was not going to change anything, and so far Betty hadn’t done anything to deserve more.

Finally, however, Annabelle does tell her parents. This occurs after the third Betty incident, in fact, making use of the Rule of Three In Storytelling.

Toby

We are not immediately sure whether Toby has a dark side to him. He doesn’t want any food, but what does he want?

I’m reminded of the Galloway character in the Jennifer Lawrence film Serena, in which a weird dude walks around in an almost supernatural way. In the adult film the character didn’t work. Partly because of the Galloway character in my opinion, who is two-dimensional and not that interesting. He is two-dimensional precisely because we don’t know what he wants.

Lauren Wolk avoids this pitfall. Toby is introduced with a backstory in chapter three, after Annabelle’s first encounter with Betty. He soon proves his goodness to us, however, when he quietly intervenes in a bullying incident. (A true Save The Cat moment.)

PLAN

Wolk sets up a mystery. Although this is not a mystery novel per se, there are mystery detective elements as Annabelle sets about on her own fact-finding missions, determining of her own accord whether Toby could be seen from the belfry, and if Betty was even up there at the time of the rock incident.

BIG STRUGGLE

The climactic incident, after the wire trap, after the lost eye, is when Betty and Toby both go missing. This happens Chapter 12, about p120 out of 290pp. A little less than halfway through.

ANAGNORISIS

Because this is a story retold by a first person narrator, after a distance of many years, the anagnorisis is handed to us (the reader) at the very beginning, and even used on the yellow version of the book cover:

(The first chapter is actually bookended by these two sentences.) This guides the young reader in advance and will probably help less experienced readers understand the themes. (Another example of this technique can be found in the opening of Twilight by Stephenie Meyer.)

When it is clear that Aunt Lily believes Betty’s story that Toby pushed her into the hole in the ground, Annabelle realises that some people will believe anything so long as it suits their own preconceived view. She realises that there are good lies and bad lies — that the world is not black and white.

By the end of the story Aunt Lily has realised that she was quick to judge Toby. Of course, Aunt Lily’s anagnorisis is a lesson to the reader not to judge hastily.

NEW SITUATION

This story has a classic fugitive arc. In children’s literature it’s often another child or an animal that the child rescues and nurtures. Courage The Cowardly Dog takes in the Hunchback of Notre Dame in The Hunchback Of Nowhere. In the case of Wolf Hollow, Annabelle is also harbouring a grown man in the hayloft. (Since this is literary and not horror comedy, the author did well not to make this sound creepy. I’m not sure it would work so well if it were set in 2017.) Haylofts are thought to be nurturing, comfortable places to sleep. E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web is another excellent example of the hayloft as warm, nurturing place. A bed of hay is a common feature of utopian (or snail under the leaf) stories. (Not true here in Australia — snakes and poisonous spiders keep me out of such places, but ‘universal symbolism’ is Northern Hemisphere-centric.)

“The loft will be fine,” he said. “It smells good up there. And I like the doves.”

An a fugitive arc the goodie eventually proves their goodness to the public. One feature of mythic journeys is that the anagnorisis happens in front of an audience. In this case Toby had to get into the hole and rescue the girl he supposedly harmed.

The problem with grotesques, though, is that in stories they don’t get happy endings. Experienced readers will have expected this as soon as we learned about Toby’s hand. It was inevitable from the set up that Toby would be shot.

However, it was not so inevitable that Betty died. The author avoided melodrama and achieved mimesis by having Betty die undramatically of systemic infection.

We can extrapolate that life will go on as before, but Annabelle is now an adult, or closer to it. That makes Wolf Hollow a coming-of-age story. Annabelle has been drawn into an adult world and there’s no going back. Aunt Lily may or may not be a tad kinder.

In America, lying can never be an act of caring. We find it hard to accept that lying would be protective, this is an unexamined idea. In some countries, not telling, or a certain opaqueness, is an act of respect.

Esther Perel

FURTHER CHARACTER NOTES

Ruth

Annabelle’s best friend Ruth is a dark-haired, red-lipped, pale girl with a quiet voice. We know immediately that she is not the star of the story. Such girls do not often star in middle grade fiction. (They may find themselves viewpoint characters.) Instead, this girl loses an eye. I’m reminded of Mary and Laura from the Little House On The Prairie series. Laura is the spirited girl with gumption and attitude; Mary is expendable (plot wise) and sure enough, Mary too becomes blind. (The fact that Mary Ingalls became blind in real life is beside my point. It’s possible Mary’s subdued ‘personality’ was emphasised to fit how she became, by necessity, after losing her sight, and her freedom.)

Annabelle’s younger brothers, age 9 and 7, are repeatedly portrayed as existing in the world of childhood, in stark contrast to Annabelle who at age 12 is just starting to encounter adult problems such as prejudice and injustice. Henry and James run around gleefully, eat without self-consciousness and must be protected as the children they still are.

For a while, being included in these conversations had made me feel tall. Now I was ready to be eleven again and back up in bed like my brothers.

Townspeople

Other characters exist to flesh out the town and contribute to the plot — the kindly German man despised by town locals, the gossipy Annie Gribble. (Annie Gribble is somehow an onomatopoeic name. Perhaps because it contains the ‘gr’ consonant cluster, in common with ‘grumble’.)

Annie Gribble lived in a small house that we passed on our way to market. I’d only been there once, to drop off a bushel of peaches at canning time, but she’d invited us in for a glass of lemonade, my father and me, and I’d been fascinated by the switchboard that dominated her front room like a loom strung with thin black snakes.

With the snake simile in final position of that thumbnail character sketch, we are left with a very clear impression of Annie Gribble. She is not to be trusted.

The constable is a kindly fellow, big and strong, but not as good at detective work as Annabelle.

By the end of Wolf Hollow it’s clear that these minor characters were fleshed out for a reason. Annie Gribble is a very handy archetype to have in a story, for narrative purposes. As the town gossip she is an omniscient eye. In Anne of Green Gables we have Rachel Lynde who performs a similar purpose.

SYMBOL WEB

Wolves/Dogs

It is explained that Wolf Hollow no longer has wolves but used to be the place where wolves were trapped and shot. There were deep pits dug there, which the wolves would fall into. Another story with wolf in the title but not in the setting is “The Wamsutter Wolf” by Annie Proulx.

It is immediately clear that the character of Toby is the personification of a wolf — a wild creature roaming around suspiciously, misunderstood by humans. It is no surprise when something bad happens to him. The history of the wolves has foreshadowed the calamity which befalls the human-wolf. To be clear, there is nothing supernatural about this story. It’s not a werewolf tale. But this feels like a place of fantasy laid upon a real-world setting — the symbol web and the ‘evil’ newcomer and the poetic place names lend this feeling. Toby is compared to a farm dog numerous times throughout the story.

When Betty is found the ‘hunt’ for Toby intensifies.

Hollow

‘Hollow’ is a great word.

We might think of it romantically, as we are encouraged to do in Gilmore girls with the name ‘Stars Hollow’ — a genuine utopia, separate from the ills of the world by virtue of its being in a bit of a ‘hole’ (which has completely different connotations).

More generally, ‘hollow’ means ‘having a hole or empty space inside’. This describes the townspeople who so easily discriminate against those who are different from themselves.

It is eventually revealed that two of the three guns Toby hauls around are broken. ‘Hollow’ weapons, ‘hollow’ threats — symbols of how Toby looks dangerous but actually isn’t.

Plot wise, it is significant that Betty falls into a literal hole in the ground. This is of course a form of retribution, and readers are encouraged to examine our own glee, especially when it’s revealed how close Betty came to death.

See also: Punishment in Children’s Literature.

But when Annabelle has her final idea she has it at the Turtle Stone, which is at a high point. In stories, characters have revelations in high places. Like Moses in the Bible.

See Also: The Symbolism Of Altitude

Toby’s Hand

Toby’s scarred and deformed hand is a distinguishing feature eventually used to prove his real identity. This trope is used to comic effect by Daniel Handler in A Series of Unfortunate Events, with the tattoo of an eye on Count Olaf’s ankle.

It is significant that Toby’s hand is disfigured because the author is making use of the Red Right Hand trope.

Toby is a Grotesque (and grotesques often have Red Right Hands). A grotesque is ugly on the outside but good on the inside. (Or if they’re bad, it’s because they’ve been treated badly.) But because of his “Red Right Hand”, the townspeople (as well as the readers) have been trained to see Toby as evil. There are good deformities and bad deformities, and having a deformed hand is not a good one, in literature.

Though most people probably think of the Nick Cave song these days, the term originated in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Before that, there are references to red hands in the Bible. Toby is clearly a Jesus figure — ostracised by many for his difference, an aesthete, a long beard, a carpenter, intrinsically good, loves children.

In any case, the history of storytelling has taught us that characters with red hands might be supernatural and also very, very bad. So when Toby turns out to be a good guy, Lauren Wolk has subverted reader expectations, and hopefully the anagnorisis for the reader is: Don’t judge people at first sight.

RELATED

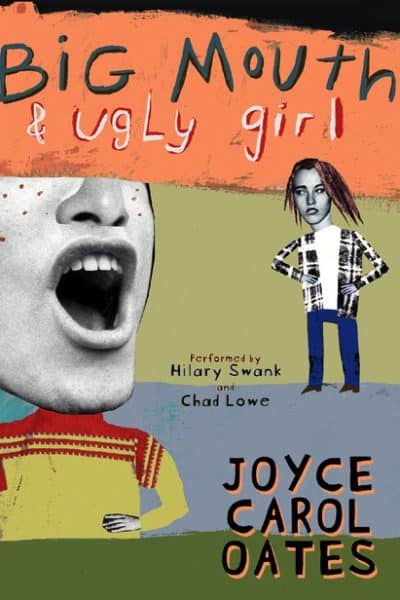

Another novel, for slightly older readers perhaps, deals with questions of right and wrong, appearance vs reality. Big Mouth and Ugly Girl by Joyce Carol Oates.

High school junior Matt Donaghy is considered an okay guy. He gets good grades, writes for the school paper, is in the Drama Club, and is known for his witty, if immature, humor. Students and teachers seem to like him. But one day he says something that makes a few classmates think he’s out to bomb the school. The school principal is notified, the police are called in, and rumors are abuzz. Even his buddies doubt his innocence, and none of the guys come forward in his defense. There is, however, someone else who overheard Matt’s statement and understood his mocking intent. School renegade Ursula Riggs, or “Ugly Girl” as she refers to herself, doesn’t know Matt very well but reveals what she heard and the context in which it was said — even though her parents instruct her to mind her own business. But even if Ursula can help Matt clear up this misunderstanding, will life at Rocky River High School ever be the same again?