- Laura and Mary Ingalls

- Georg(ina) and Anne

- Ramona and Beezus/Susan Kushner

- Bean and Ivy

- Clementine and Margaret

- Junie B. and Tattletale May/Richie Lucille

Each of these pairs represents a perceived dichotomy of girlhood: the girly girl versus the “tomboy”.

While I use the word “tomboy”, the speech marks indicate my disdain for the very concept. A girl who likes rough-and-tumble and dressing for practicality is no less of a girl. The word itself upholds a narrow notion of what it means to be a real girl.

This is the very political position taken by many popular modern writers of chapter books and middle grade novels. Publishers and readers love it, right now. This upturns the now offensive political position of earlier children’s stories; until very recently, if girls were depicted in children’s books at all, they were the minor characters — the inevitable sisters and mothers and giggly schoolyard opponents. Even books for girls and about girls actively encouraged domesticity in their young readers, preparing them for their futures as mothers and housewives by returning them safely to the home, if they ever left home at all.

Modern literature for girls is mostly the inverse of that. Modern girls read about girls doing brave, adventurous and amazing things. It’s a truism that the most interesting kidlit characters are proactive, sometimes naughty, often cheeky. Imperfect and relatable, in other words. Sometimes they are average kids in every way (oftentimes ‘underdogs’); other times they have a special super power.

I don’t just mean ‘super power’ in the fantasy sense. Modern heroines of kidlit might be a Hermione trope — good at school work and often annoying in girly kinds of ways, but useful to the boys in their quest for self-knowledge due to her extensive knowledge on a subject, which must take place (rather boringly) off the page, since swotting requires many hours of solitude.

What It Means To Be A ‘Girly-Girl’

- Upholder of social rules (a la ‘Tattletale May’ from the Junie B. Jones series)

- Feels the need to look pretty and also judges others on their appearance

- Bookish

- Good at memorisation

- Well-behaved in school, sometimes a teacher’s pet.

- Helps the mother at home and is often the ‘mother’s pet’

- Aligns self with adults who have conservative, old-fashioned attitudes about a child’s place: Children should be seen and not heard.

- Fearful, anxious temperament

- No sense of humour, though she may develop a sense of humour/how to have fun if she ‘learns’ it from tomboy types

What It Means To Be A ‘(Tom)Boy’

- Breaks the social rules. Is sometimes punished, other times rewarded

- Dresses for practicality rather than to look pretty, and is interested in other people for what they can do rather than what they look like. Non-judgemental.

- Outdoorsy/sporty

- Tasks such as rote memorisation are rejected due to their boringness.

- Misbehaves in school. Has trouble sitting still. Drawn to movement.

- Is mischievous at home and is often in conflict with the mother, aligning self with the father (who may often be absent)

- Aligns self with adults who are open-minded, kid-friendly and even tempered and fair

- Open to adventure; unafraid of consequences; brave

- Keen sense of humour

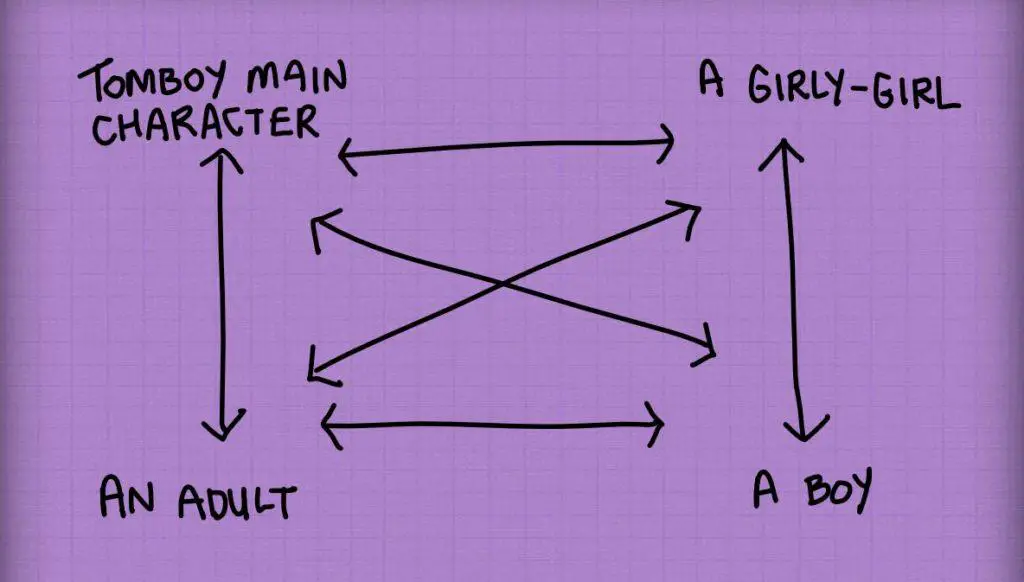

Typical Character Web Of A Chapter Book For Modern Girls

Opponent 1: The Girly-girl, and perhaps her posse of proto-mean girls.

This opponent highlights the rambunctious nature of our tomboy main character, and she will often get the tomboy into hot water using subversive tactics. But she will ultimately be punished. This punishment will ‘serve her right’ for her extreme femininity. She’ll be grossed out or she’ll get her clothing dirty despite having a distaste for germs or she’ll have a wardrobe malfunction or her beautiful hair will get pulled or ruined in some way. Although the opponent in a character web is designed to highlight a shortcoming in the main character, the girly-girl mainly serves to highlight the tomboy’s strengths.

Opponent 2: The Boy

The boy opponent is often on the edge of boy-dom himself as we rarely see him with all of his buddies. He is drawn to the tomboy girl without seeming to help himself, and he often tries to attract the girl’s attention with silly tricks or bravado. The relationship between the boy and the tomboy main character is a proto-love story. As is true for romantic comedies for adults, the tomboy and the boy must start out as rivals, and learn over the course of the story that they actually have a lot in common. This boy will often live nearby. He has probably known the tomboy for a while, and the beginning of the series marks the beginning of their friendship arc.

The boy highlight’s our tomboy heroine’s unpleasant tendency to be mean for mean’s sake. This is a Pride and Prejudice sort of thing going on; the tomboy dislikes the boy simply because he is a boy. But she comes round to his way of thinking because this boy is basically fun.

Opponent 3: An Adult

This will be a parent (almost always the mother — fathers tend to be fun), a teacher (an old-fashioned, grumpy type who doesn’t seem to like children), or a neighbour person (a cranky neighbour who won’t let kids onto the lawn or a shopkeeper who thinks kids only thieve).

These adults highlight the tomboy heroine’s inability to conform to an old-fashioned ideal; that children should be seen and not heard. But mainly these adult opponents highlight the child’s resilience, daring, bravery and ability to think themselves out of trouble. Our heroine seems jovial and full of the joys of life against these dour characters whose main concern is doing housework, rote memorisation, and boring daily routine.

In a regular character web, each opponent is in opposition to each other. That’s not always the case for the girly-girl and the teacher/mother figure, who are one and the same person. But sometimes, in the slightly more complex books, the adult is an ally as much as an opponent, and can see through the ingratiating tendencies of the underhanded girly-girl.

Which opponent comes out looking worst in most of these stories?

The girly-girl, of course. While the boy character is generally a secret ally-opponent, and the adults are often as kind as they are ignorant of kidland politics, the girly-girl has no redeeming qualities. However, she is sometimes redeemed by the end of the book/series. Usually it’s because she’s learned something from the tomboy, or she has realised that dressing in pretty clothes and focusing on image is leading to her downfall.

The tomboy main character far less often learns anything useful from our girly-girl. On a surface level, the tomboy does not start dressing in pink, realising that pink is okay after all. She doesn’t grow her hair long or start to take more pride in her appearance.

One exception to this — though it’s a young adult novel rather than a chapter book — is a story by Joyce Carol Oates, Big Mouth and Ugly Girl. Stories like these inevitably become prone to all of the problems involved in the ‘makeover’ trope. It’s an almost impossible line for authors to walk.

However, in the best books of this kind, the tomboy character does learn something from the girly-girl. She generally learns kindness, which comes about from learning that there are depths to this annoying representation of walking-femininity, and that even girly-girls should be treated as rounded people. This requires a more fleshed-out subplot, where the reader, alongside the tomboy heroine, gets to see another side of the girly-girl. Sometimes the girly-girl has problems at home — absent parents, most often, who give her pretty dresses to try and compensate for their lack of parental attention. This is a lesson for parent co-readers as much as it is for young readers.

However, when a girly-girl is suddenly presented as dimensional due to basic neglect, what does this say about obvious outworkings of femininity? Girly accoutrements, however they’re handled, are generally indicators that something is going terribly wrong with that girl.

A Brief History Of Tomboys Versus Girly-Girls

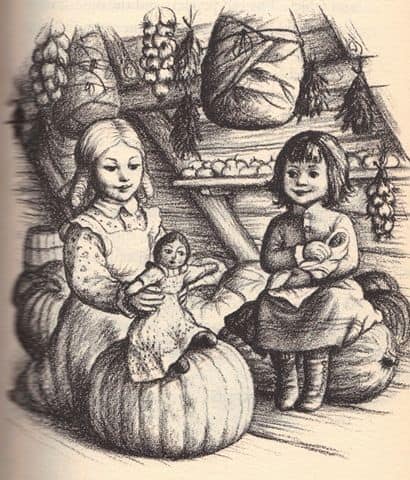

LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE SERIES

Our viewpoint character is Laura Ingalls: brave, adventurous, outdoorsy. Laura despises being cooped up inside and has to be coaxed into doing her school work. When the family moves into town she longs to be back on the prairie. Lacking a boy in the family, Laura is consistently profiled as ‘her father’s daughter’, whereas Mary is cut from the same cloth as the mother. This even extends to the colour of their hair; Laura has brown hair like her father, while Mary has blond hair like their mother.

Mary also contrasts as the feminine flipside of a prairie daughter: Mary is studious, prone to anxiety and never misbehaves. When Mary ultimately becomes blind after a bout of scarlet fever, her feminine virtues are only heightened. Now, she is resigned to a life of sewing inside, and having others describe things to her — living secondhand.

For most of the series, Mary and Laura are flipsides of a girl, but in the third Laura book On The Banks Of Plum Creek, a new character is introduced who represents not just the flipside to country girls (a rich townie) but also provides an even more exaggerated, and this time toxic, version of what femininity can mean. Nellie Oleson’s obsession with cleanliness and pretty dresses is evident when she visits Laura and Mary at their modest prairie home. She criticises their home by saying she didn’t want to wear her best dress to a country party. The reader is encouraged to condemn Nellie for such rudeness. Inevitably, the reader also condemns Nellie for her rejection of the country and also for her obsession with dresses. As unpleasant as Nellie is for other reasons, we learn to associate a love for fashion with vacuousness and image obsession.

Yet there is a line. We see time and again throughout the Little House series how overjoyed Laura and Mary are to be getting new dresses. Laura’s new dresses are simple, however, and she is at one point overjoyed to be getting a new dress made of brown fabric, when she’d been expecting Mary’s hand-me-down. The author encourages the virtue of gratitude, but the focus on clothing has the — perhaps unintended — consequence of denigrating ostentatiousness in female dress. Girls and women must take care of their appearance, but not too much.

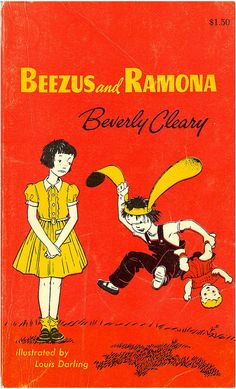

THE RAMONA QUIMBY SERIES

[Ramona] represents the kind of girl who has not been subdued by adults or the world in general.”Twentieth-Century Children’s Writers cites Ramona’s “spunk, her impermeable but often ambivalent bond to Beezus, and her unsurpassed creativity… (Cleary) never sacrifices Ramona’s integrity or intelligence.

— Librarian Kathleen Odean

Compared to Laura Ingalls, who nonetheless conforms to feminine standards of the time (even buckling down, against her nature, to be a future teacher), Ramona Quimby is a revolutionary character, and Beverly Cleary’s mischievous little girl marked a new era in realistic middle grade novels.

Ramona can never live up to standards set by her older sister Beatrice.

But Beatrice is still not a particularly girly girl. For that trope we have the ‘exaggerated Beatrice’: Susan Kushner, who is punished for her feminine accoutrements by Ramona, who just can’t seem to help pulling her golden curls. Readers are invited to take enjoyment in Ramona’s mischief, because Ramona is the viewpoint character after all, but also because Susan is not a nice girl, and the prettiness of Susan marks her out as such. From this character, readers learn that prettiness in girls is associated with meanspirited-ness, lack of originality and underhandedness:

Susan is portrayed as being somewhat snobby and overachieving; in the book of her debut, her beautiful curls become the object of Ramona’s fascination and lead to the girl’s suspension from kindergarten for pulling the curls out of curiosity. In the following book, set a year later, Susan copies a stereotypically-designed wise paper bag owl designed by Ramona during an arts and crafts session, which is destroyed by an enraged Ramona after Susan is praised by the entire classroom for her work. She is depicted as a typical perfectionist; well-behaved in class, calm, and hard-working, as opposed to Ramona’s active imagination and unintentionally troublemaking personality. However, she is a bit of a snob, exaggerating the pain felt after Ramona tugged her curly hair in Ramona the Pest for attention. Also, she did copy Ramona’s work.

Once again, we have a girly-girl who is easily upset by uncleanliness, and which an older reader might pick up as the first signs of an eating disorder:

In the final book of the series, [Susan] refuses a slice of cake during Ramona’s birthday celebration claiming that it is probably unhygienic and eating an apple instead, but soon afterward she confesses, in tears, her lifelong strive for perfection among adults, and her relationship with Ramona Quimby seems to improve afterward. In the same book, it is revealed that her parents tell Ramona to “be nice”.

— Wikipedia

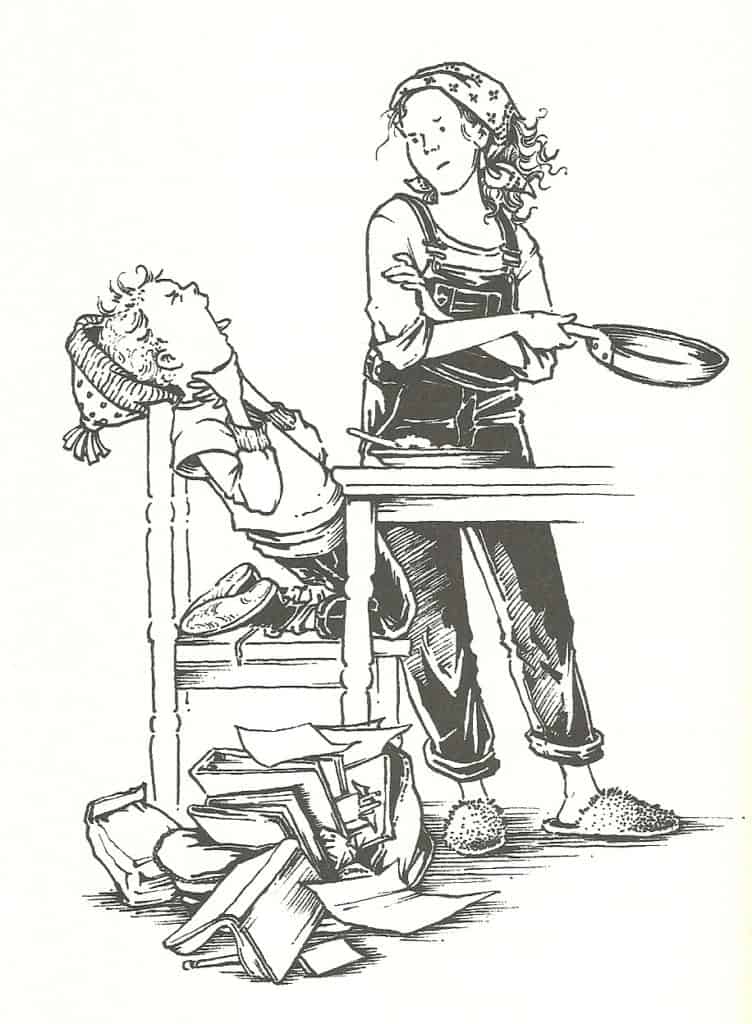

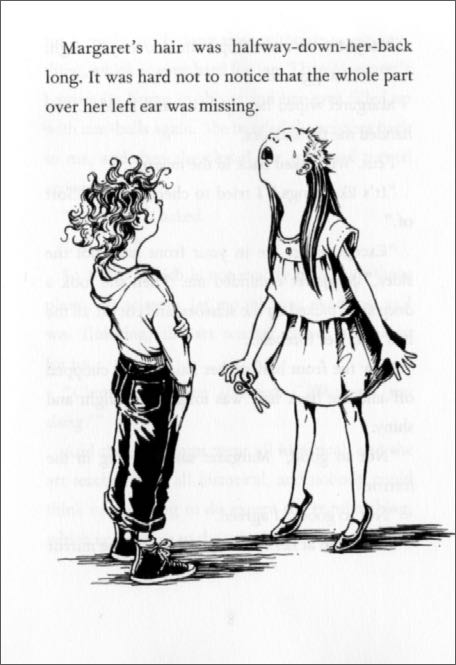

THE CLEMENTINE SERIES BY SARA PENNYPACKER

In the name of upending gender stereotypes, she might be the opposite of what readers expect from a girl. Clementine is great at math and nothing else school related. Clementine shows clear signs of ADHD, something far more often diagnosed in boys. This makes Clementine a great kidlit character — she doesn’t think too much before acting, and this gets her into trouble. She sees the world differently and is often perplexed. The illustrations of Clementine by Marla Frazee depict Clementine as a Ramona Quimby sort of girl — back in the second wave of feminism, when girls wore their hair short and their mothers chose clothes for their many pockets and durability. Clementine is shown most often in the midst of action, which is what makes Marla Frazee such a great choice of illustrator for the Clementine series — she is super good at it.

Margaret is constantly ‘punished’ for her interest in feminine accoutrements. Insofar as long hair marks a girl out as a proud owner of femininity, she is ‘christened’ into Clementine’s more masculine world when Clementine gives her a haircut, which happens near the beginning of the first book.

In the seventh book of the series, Completely Clementine, Margaret insists on wearing high heeled shoes to a fancy event and ends up breaking her ankle.

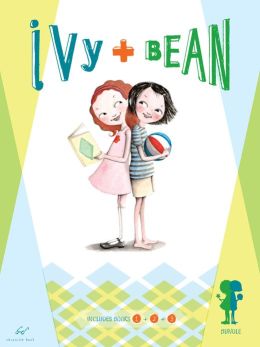

IVY AND BEAN

More than any other cover I’ve seen, this graphic design highlights a girly-girl and a ‘tomboy’ girl as flipsides of the same character. I believe this cover highlights the intention of this category of modern stories marketed at girls: That there is more than one way to be a girl. You can have fun whether or not you like to wear pink dresses.

This series works a bit differently from those above, though ultimately, the result is the rejection of extreme femininity.

Bean — our viewpoint character — lives across the street from a girl who wears pretty dresses and seems to behave perfectly. Since Bean is nothing like that, she decides she wants nothing to do with this girly-girl, despite her mother’s suggestion she go and introduce herself. Naturally, the two end up meeting inadvertently and they hit it off. The rest of the series focuses on the adventures these two firm friends have together.

Does Bean realise that girly-girls aren’t so bad after all? No. She (and the reader) realises that although Ivy looks like a girly-girl, she’s as adventurous, imaginative and naughty as Bean. Older readers especially will notice that Ivy comes from an economically advantaged home and that she is an only child, which explains why Ivy is dressed up like she is. The subtext is that well-off parents of only-girls are inclined to treat them as dolls, and if these little girls want to have real fun, they must reject their parents’ limitations by pairing up with a ‘tomboy’ kid like Bean.

Book eight in the series shows readers that even girls who like to wear pink and pretty dresses can have lots of fun.

The Ivy and Bean series shows girls that wearing pink dresses means you can still have fun, but you must nevertheless reject other aspects of traditional, stereotypical femininity, such as aligning yourself with adults, behaving perfectly at all times and feeling anxious when trying new things.