This middle grade novel features talking animals, especially mice, toys and doll’s houses. The Mouse and His Child is no Velveteen Rabbit, however.

As Margaret Blount says, The Mouse and His Child defies classification, and is therefore of interest to critics and children’s literature enthusiasts:

Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child (1969) is such a strange, haunting and distinguished book that it is very difficult to classify. It is about toy mice, yet the clockwork father and son move through a world in which small animals act out human dramas.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

In some ways it can be compared to Charlotte’s Web, but Charlotte’s Web continues to be more widely known.

The story shares commonalities with E.B. White‘s Charlotte’s Web by contrasting with a large part of children’s literature in the sense of occasional use of advanced vocabulary, a willingness to include adult themes, and talking animals.

Wikipedia

Why is The Mouse and His Child not more widely read today? Townsend explains that The Mouse And His Child is clearly North American but has, for some reason, been far more popular in Britain, where it is regarded a classic. Some people speculate it’s due to ‘hygiene’ — that picking toys out of the dump isn’t clean.

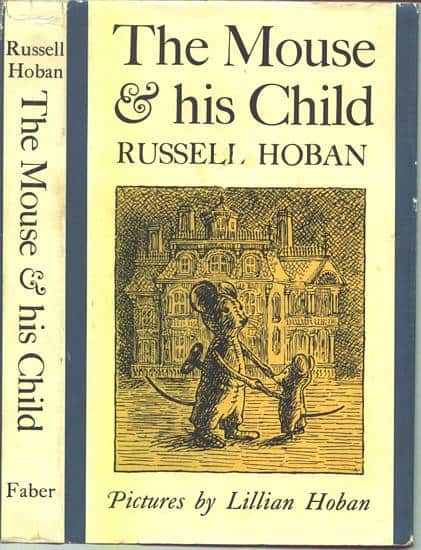

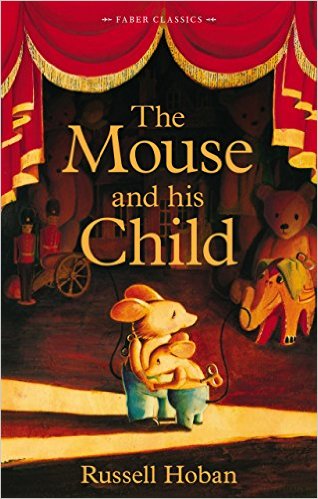

That said, the book has been reprinted and re-illustrated

“What are we, Papa?” the toy mouse child asked his father.

“I don’t know,” the father answered. “We must wait and see.”

So begins the story of a tin father and son who dance under a Christmas tree until they break the ancient clock-work rules and are themselves broken. Thrown away, then rescued from a trash can and repaired by a tramp, they set out on a perilous odyssey to follow the child’s dream of a family and a place of their own. What happens to the mouse and his child in their search for the magnificent doll house, the plush elephant, and the tin seal they had known in the toyshop is a tale to remember and return to.

And made into a film back in 1977.

The original edition was illustrated by Russell Hoban’s wife, Lillian. There is a distinctly Disney feel about it. Lillian Hoban is perhaps best known for her I-Can-Read illustrations for the Arthur series.

Arthur Levine commissioned illustrator David Small to do the artwork for their updated edition in 2001. These illustrations remind me more of Sir Quentin Blake, but with close attention to shade and tone which adds a slightly noir feel.

What is the story about?

The mice are searching for the things that people want: happiness, a family, a home, self-winding freedom, from their bright morning in the toy shop at Christmas to their ending on a birdhouse platform by a railway line, near the town dump. There is a glimpse of shining perfection as the toys — the mice, elephant, seal and doll’s house that come so largely to the story — wait on the shop counter to be sold. The mice dance in a circle when wound.

To be bought is to be born. For four years the mouse father and son dance under the Christmas tree, always put away in their box until, pounced on and broken by a cat, they are thrown away. Repaired by a tramp who can only make them walk straight, they follow an endless road, tramps themselves, finding their way into a place like Cannery Row only far more sinister — the town dump ruled by the exploiting bandit Manny Rat, the underworld king who wears a greasy dressing-gown and lives in an old TV set.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

Influences And Intended Audience

Hans Andersen with the clockwork nightingale and lead soldier, Kingsley with the fate of the lost doll, Collodi with the strange quest of the puppet who wanted to be a boy — all tell of the strange quest of the puppet who wanted to be a boy — all tell of the human sadness of toys, which is something that adults see, and one wonders if children really enjoy The Mouse and His Child. As an adult it is impossible to read it unmoved.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

Multiple Layers

Russell Hoban’s The Mouse and His Child (1967), about the quest of a pair of linked toys to find a home and be self-winding, is a multi-layered book, accessible at more than one level. It can be read by children quite simply as a story of the adventures of clockwork toys, and by adults as a haunting human progress. The pathos of a toy’s life — the decline from freshness, beauty and efficiency toward the rubbish dump, the rusting of bright metal, the rotting of firm plush — is the pathos of human life transposed. The mouse and his child are loving people, totally interdependent. There are clear allegorical meanings — any child can understand the longing to be self-winding — and strong, often funny, sometimes savage satire, though some of this may be beyond the grasp of children. Manny Rat, who rules the rubbish dump and deals with recalcitrant toys by consigning their innards to the spare parts can, is a splendid villain.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

Motifs, Symbols, Satire

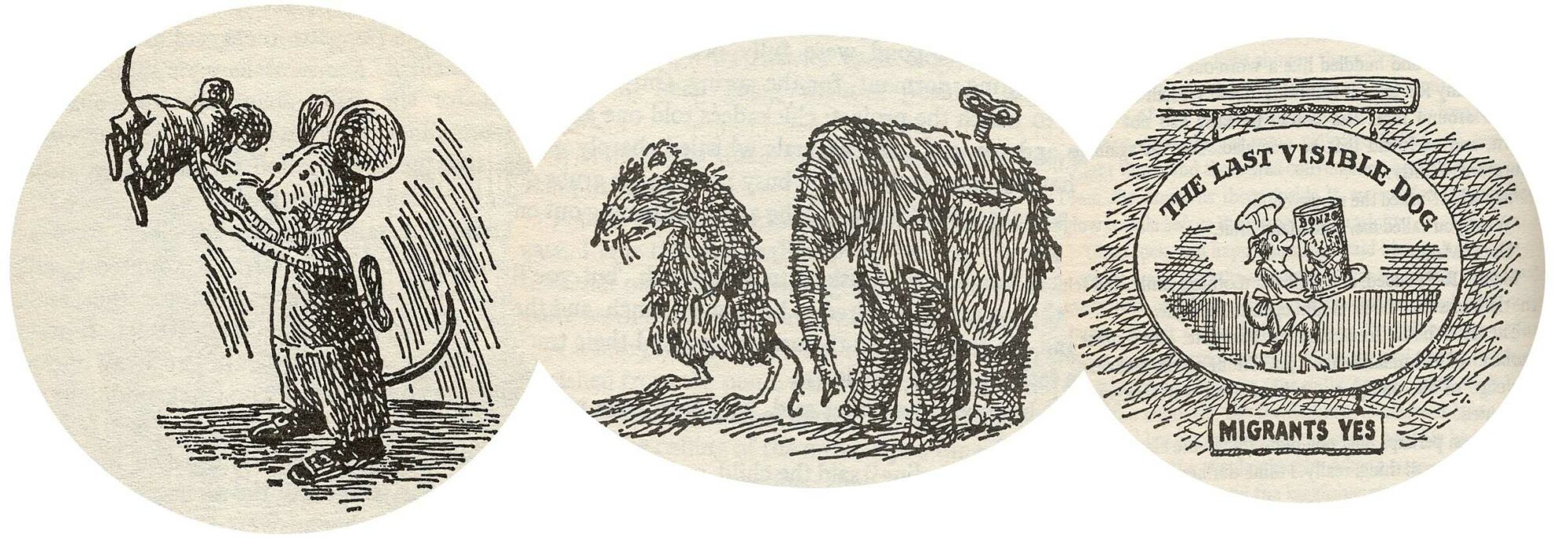

Likeness to the human world is both satiric and symbolic. The mice are sent to rob a bank by the rat; the chipmunk behind the counter pushes ‘the alarm twig’ and a badger guard eats the rat. The mice get involved in a territorial war between shrew armies with big struggle cries of ‘ours’ and ‘onwards’; weasels casually eat the shrews; owls catch the weasels. A recurrent motif is an old empty dogfood tin with a picture of a dog in a chef’s cap carrying on a tray another dog in a chef’s cap. The mouse father’s heart is his clockwork centre. He has patience, courage, sad endurance. The child, with less clockwork, has room for dreams of family and home — ‘I want the elephant to be my mama and the seal to be my sister and I want to live in the beautiful house.’ In their hopeless quest, the mice somnambulate through impossible tasks, like Tess in the potato field. They pace the Crows’ stage in an incomprehensible play…they are harnessed by the muskrat to a saw device for felling a tree, which takes all the winter, they fall to the bottom of a pond. Their physical disintegration is a persistent theme. When they do at last find the doll’s house its fate has been that of many real ones. It has been ravaged by fire and ‘become in its romantic ruined state a trysting place for young rat lovers, then a social and athletic club.’

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

The Significance of ‘Wind-up’ In Wind-up Toys

Maria Nikolajeva writes, ‘The very idea of a windup toy is repetition, predestination, things going on forever. Another aspect is absence of change and free will.’ If the mice were to dance Christmas after Christmas, however, there would be no story. So although the adults have an idea of what children might enjoy, the children (or child characters) are wrong. When the mouse child breaks the rules, this is a step away from circularity (and from the iterative language). Everything that happens after the mouse child is expelled from paradise is tragic but necessary. The message seems to be that linearity is preferable to circularity:

“There is no going back,” said the father…we cannot dance in circles anymore.

The Mouse and His Child

The Doll’s-house Symbolism

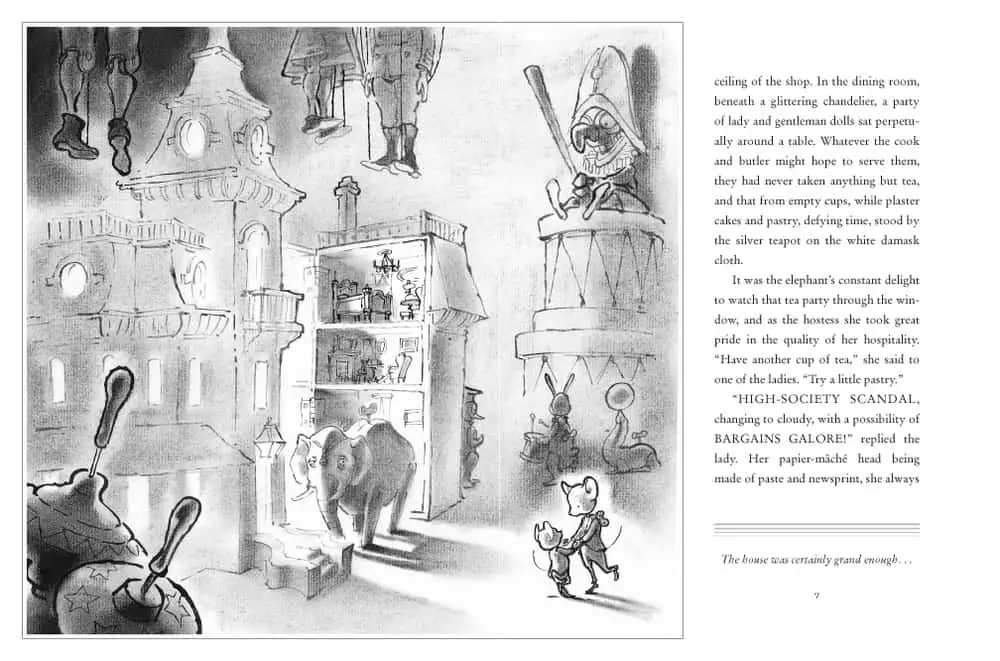

The doll’s house is inhabited by wonderful papier-mâché models talking in scraps of newsprint, and is an enviable mansion with every detail exact, one of those American country houses whose adjectival accompaniment is always ‘decaying’ and ‘Southern’ as if they have to end up in Tennessee Williams land. And indeed, this one decays and suffers as doll’s houses, and some real ones, often do.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

Manny Rat

Manny Rat is your archetypal rag-and-bone man, which rats often are in children’s books with personified animals:

The rat is hideously real, always foraging, exploiting everything it meets, using old clockwork toys to fetch and carry, mending them just enough to keep them going like abused and broken-down horses, running sordid sideshows that offer and give nothing, and taking his profit from their wretched owners, miserable beetles and crickets.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Jungian critics have fun with this novel. There is an obvious erotic subtext, ‘especially in the rivalry between the mouse father and Manny rat, and the elephant’s open aversion for Manny, who has, we might say, raped her.’

Maria Nikolajeva uses this book as an example of a book which breaks away from the idyll established in the beginning. Take note of what Nikolajeva refers to as ‘iterative’ time:

The Mouse and His Child is most often referred to as toy fantasy. However, I would like to show that […] it depicts an attempted, successful or not, to break away from idyll, which is often expressed by the change in temporal pattern of the novel from circular to linear. The Mouse and His Child starts with a perfect image of childhood, a doll house, a self-sufficient world existing wholly in the cyclical time:

…the dolls never set foot outside it. They had no need to; everything they could possibly want was there … Interminable-weekend-guest dolls lay in all the guest room beds, sporting dolls played billiards in the billiard room, and a scholar doll in the library never ceased perusal of the book he held … In the dining room, beneath a glittering chandelier, a party of lady and gentleman dolls sat perpetually around a table…

It was the elephant’s constant delight to watch that tea party through the window…

The Frog

The chief supporting characters in this strange nightmare are ‘Frog’, a figure of destiny who inhabits an old glove and makes his way with herbal remedies and fortune telling, a philosophic muskrat, a terrapin who is a thinker, scholar and playwright, two crows who run an experimental theatre company, a kingfisher and a bittern, both helpful characters represented as do-it-yourself expert and a solitary bachelor fond of fishing.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

Food

Other interesting things about this book are that it’s very much about eating and being eaten up, even though the toys themselves can’t and don’t need to eat (nor do they wish to become human, unlike in The Velveteen Rabbit, for instance).

Death

The Velveteen Rabbit makes a good counterpoint here:

Because these characters are toys, death is treated differently, too.They cannot die, which means the story takes place over many more years than your typical children’s story. ‘…all these violent deaths do not affect the toys, just as “adult” deaths most often do not affect children. […] The author introduces a special kind of death for the toys, which they go through, as ritual prescribes, three times. Since death, for toys, unlike all other deaths in the story, is reversible, they are reborn like the returning gods.‘ Notice that after each destruction and resurrection the mice reemerge with new qualities.

[…]

The happy ending does not dispel the lingering sadness of the clockwork pair, the father doomed to travel forward through the world and the son (who is joined to him) backwards. Helpless when they are not wound up, unable to stop when they are, they are fated like all mechanical things to breakage, rust and disintegration as humans are to death.

[…]

The path of every toy is always downwards. Though they share with humans apparent death (by smashing) and strange resurrections (by mending), they do not, like humans, have a high noon. The Velveteen Rabbit (Marjery Williams, 1912) has once again the them of the toy made real and immortal by love. The Rabbit is quite new. Bright and plushy he comes to the Boy at the top of a Christmas stocking, at the peak of his physical perfection, and ‘for at least two hours the Boy loved him.’

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

The Mouse and His Child As An Influential Mouse Book

Margaret Blount compares the mouse of this book to others that have followed since:

Mice who do stand out for their individuality and sheer strength of character sometimes appear in other settings; The Mouse and His Child of the unforgettable endurance are really toys and not mice at all; the great Reepicheap is a Talking Beast, one of many; Stuart Little is notable for being a social misfit and Tucker, of The Cricket In Times Square, outstanding for his untidy antique collection and his hidden riches.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount