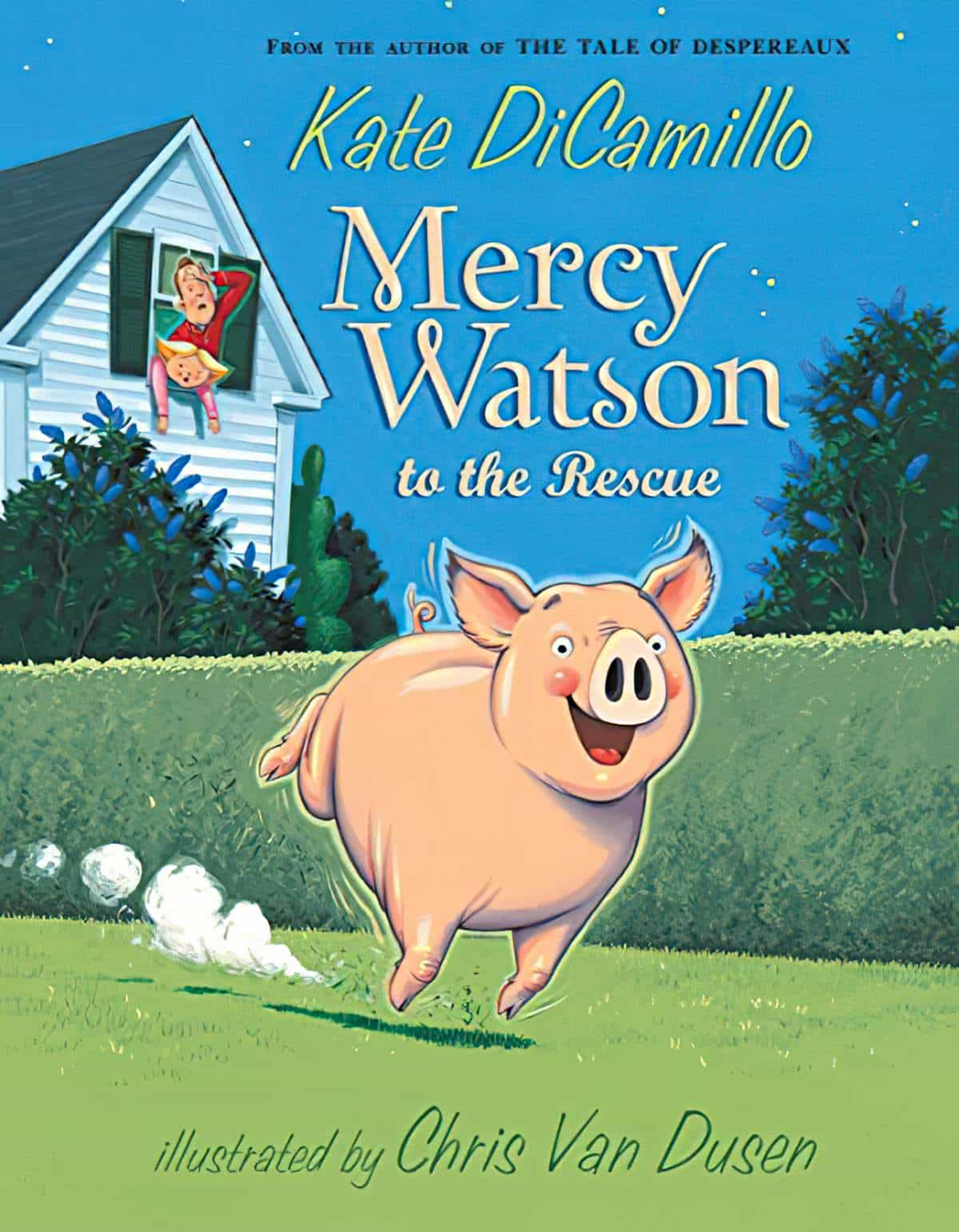

Mercy Watson To The Rescue (2005) is a picture book divided into chapters for the emergent reader, written by Kate DiCamillo, illustrated by Chris Van Dusen. I love the Mercy Watson series, and have previously written about Mercy Watson Goes For A Ride and Mercy Watson Thinks Like A Pig and Mercy Watson Fights Crime.

This instalment is similar to Mercy Watson Fights Crime, because she ends up saving the day, purely by accident!

SETTING OF MERCY WATSON TO THE RESCUE

- PERIOD — A 1950s-ish era which could easily be right now, especially since chrome toasters and retro kitchens have come back into fashion.

- DURATION — Some picture books take place over a 12 hour day; others over a night. This one takes place overnight. Excitement for the night-time is built up at the start of the story. We just know Mercy is not going to stay in bed, and then we know she’s not going to stay in her parents’ bed.

- LOCATION — In a fictional American suburb

- ARENA — Mercy stays near the house, and ventures to the house next door in search of sugar cookies. Even the chase sequence takes place close to home, around and around Eugenia and Baby Lincoln’s yard.

- MANMADE SPACES — The houses are very Wisteria Lane, and similar to the set in Desperate Housewives, the Mercy Watson series is a bit of a parody of suburban life. In this case, the comedy derives from suburban parents who would normally have children but who instead keep a pig.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Mercy should really be on a farm but the comic juxtaposition works because Mercy lives in a house and sleeps in a child’s bedroom.

- WEATHER — The night-times of the Mercy Watson books are as pleasant as the daytimes. Cold and damp are never an issue in this utopian suburbia.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Only the toaster, perhaps? Also the fire engine. It’s the technology that makes this story feel straight out of the 1950s, as well as the gendered roles of the Watson parents, and the two spinsters who in more enlightened times may live separately, or with their female lovers, for instance. (This series is in need of some fanfic.)

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — In the hierarchy of human struggles, this is basically a story about neighbour conflict. We don’t always agree with our neighbours about what and who should be allowed into the neighbourhood, be it noise, tree species, barking dogs or… pigs.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The Watson adults are comically wrong about their pig daughter, who they incorrectly anthropomorphise. This aligns with how many of us are with our pets, attributing very human motivations to them. Another picture book which goes into this aspect of pet ownership is one by Lauren Child, Who Wants To Be A Poodle, I Don’t. In that story, the doting owner learns to treat her dog like a dog. That will never happen in the Mercy Watson series.

White people generally believe that dogs have human emotions and that they are capable of loving certain TV shows, films, and music. “Buster just loves watching Six Feet Under!” Even though most dogs would enjoy watching Hitler if he were getting attention every time it came on the TV.

Stuff White People Like

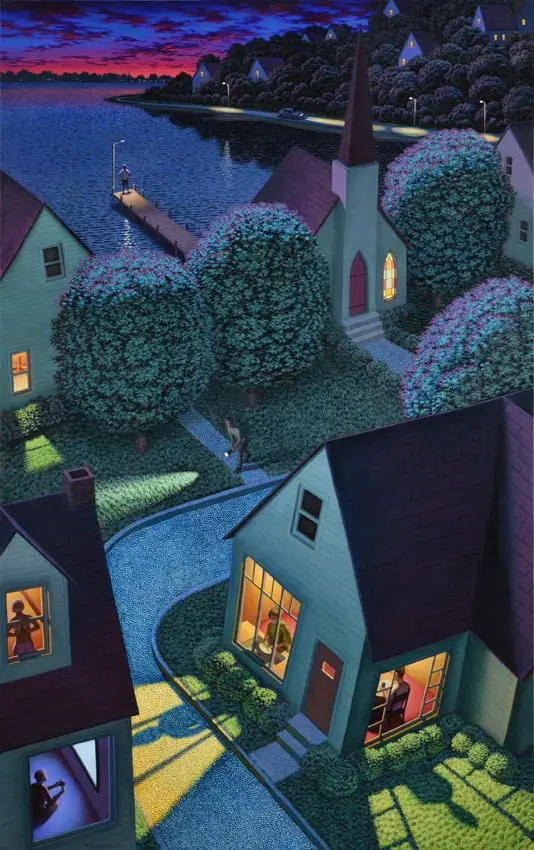

Chris Van Dusen’s illustrations of ‘perfect suburbia’ remind me a little of work by Leonard Koscianski, another American artist. The crisp, clean lines are similar, and so are the choice of angles. A number of the Mercy Watson stories take place overnight, yet the task of the illustrator is to make the night as clear as the daytime. Both art styles achieve this with a dark sky and long, dark shadows, but strong light sources ostensibly coming from the moon.

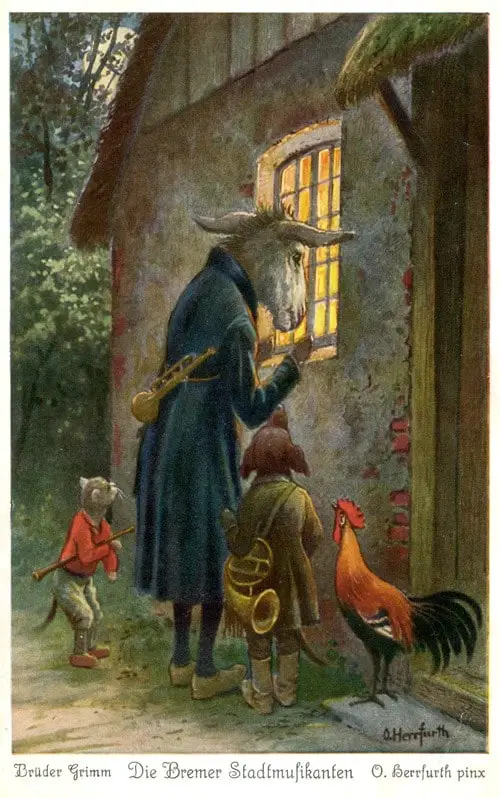

These images of suburbia go back as far as suburbia itself. The illustration below is German, but again reminds me of the suburbia created by Van Dusen.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MERCY WATSON TO THE RESCUE

PARATEXT

To Mr. and Mrs. Watson, Mercy is not just a pig — she’s a porcine wonder. And to the portly and good-natured Mercy, the Watsons are an excellent source of buttered toast, not to mention that buttery-toasty feeling she gets when she snuggles into bed with them. This is not, however, so good for the Watsons’ bed. BOOM! CRACK! As the bed and its occupants slowly sink through the floor, Mercy escapes in a flash — “to alert the fire department,” her owners assure themselves. But could Mercy possibly have another emergency in mind — like a sudden craving for their neighbors’ sugar cookies?

marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

Mercy the Pig is one of those hapless but lucky archetypes from comedy. Mr Magoo always springs to mind when I try to think of other examples, but there are a number of white men in modern shows who fit the same bill.

- Ted Lasso, about a guileless American football coach enlisted to coach a British soccer team. He’s never done this before and knows nothing about it.

- George Kostanza of Seinfeld was a mendacious ne’er do well, but he also had a surprising amount of (shortlived) luck in love and career, precisely because he fit the trusted demographic. Kostanza also ended up managing a football team at one point.

- Mighty Ducks is a 1992 film in which ‘a self-centered Minnesota lawyer is sentenced to community service coaching a rag tag youth hockey team.’ Of course the coach’s unconventional methods work.

- Major League is yet an earlier example from 1989. LoglineThe new owner of the Cleveland Indians puts together a purposely horrible team so they’ll lose and she can move the team. But when the plot is uncovered, they start winning just to spite her.

These stories resonate with audiences when they achieve earnestness. There are fewer examples of female or PoC characters who achieve greatness while completely ill-qualified to do, banking on sheer, unmitigated luck. So Mercy Watson is a nice comedic exception to an archetype. In each story she saves the day (or night) but only through sheer dumb luck. While focused on hot, buttered toast, or led only by her carnivalesque desire for fun, she ends up foiling the baddies or, in this case, accidentally rescuing her parents.

DESIRE

Mercy wouldn’t be so adorable if she were motivated purely by greed for hot buttered toast. Baddies are motivated by greed. So Kate DiCamillo opens with Mercy in bed and feeling very loved. The lullaby makes her feel like hot buttered toast. This feeling of security resonates universally, and especially with a young audience.

In this way, DiCamillo unites Mercy’s surface desire (for eating hot buttered toast) with her deeper desire (to feel like she’s just eaten hot buttered toast — for love and security.) If we hadn’t already worked it out from reading earlier Mercy Watson books, now we know for sure: Mercy’s desire for toast is always a desire for something deeper.

OPPONENT

A story always achieves more complexity and depth with a two-fold opponent web. Oftentimes storytellers create conflict with the in-group (the family, friendship group) before bringing in the Minotaur opponent, which will either unite them together or tear them apart.

How can children’s writers utilise this complexity without sacrificing the cosiness and security of home?

In the Mercy Watson series, Kate DiCamillo demonstrates a workaround: The two old ladies next door are the in-group opponents. Well, one of them is. Eugenia. The spinster sisters fir the thin-fat duo archetype, and their personalities match their BMI. Eugenia is scrawny and mean and unempathetic. We want to see her punished a little. Meanwhile, the younger sister, “Baby”, is under her thumb, slightly stupid and basically nice.

Kate DiCamillo also achieves complexity by switching point of view from the Watson household to the household of spinsters next door. At this point, Mercy becomes Baby’s opponent, peering in through the window.

Baby is a child stand-in adult character and is terrified by the spectacle. This is an old storytelling trope and when I think of any harmless creature looking scarily in through a window I think of “The Town Musicians of Bremen”.

But there are many, many examples of scary things peering in through windows. We have long been terrified of the entry points to our houses. Before it was windows and doors we were terrified of chimneys.

When writing for children, storytellers sometimes take the scariness out of the creature by turning it into a lovable character who is only there because he’s looking out for you. The Tomten stories from Scandinavia are a good example of that inversion.

PLAN

Since Mercy has no plan other than to follow her hindbrain desires, the Lincoln spinsters next door come in handy in this phase, too. When Mercy terrifies Baby Lincoln at the window, Eugenia Lincoln calls the firebrigade, then seems to forget she has done it, giving chase to Mercy, hoping to scare Mercy off her lawn. (I don’t fully blame her. Pigs make a notorious mess of land, any land.)

THE BIG STRUGGLE

A good carnivalesque romp will quite possibly involve a chase sequence. Meanwhile, next door, the climax involves a bed which is teetering on falling through to the ground level, seriously injuring Mr and Mrs Watson.

Notice how Kate DiCamillo keeps the excitement going at both addresses, not just one. Each household features its own mini story, complete with drama.

ANAGNORISIS

Sometimes, especially in comedy, the characters think they understand something but they are wrong. The Watsons think Mercy is even more wonderful than they previously believed. She is a ‘porcine wonder’ for going to find help as their bed broke through the floor.

Another layer of comedy derives from the fact that it was probably Mercy getting into bed with them in the first place that ‘broke the camel’s back’. Not only did she fail to summon help; she caused the disaster in the first place!

There’s another revelation for the reader: When Mercy and Eugenia are found, Eugenia is hugging Mercy, belying a represed maternal instinct of her own.

NEW SITUATION

All of the Mercy Watson books end in the same way, with the cast of characters sitting down to enjoy toast. In this one, Eugenia Lincoln also sits down at the table, though she has no toast on her plate and she eyes Mercy suspiciously, declaring that pigs should not be allowed at the table.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Extrapolating a bit, Eugenia would also like to be a mother, and this is why she has kept the nickname of “Baby” for her younger sister (who is nonetheless in her late middle-age).

RESONANCE

By remixing a number of long-established, successful tropes, Kate DiCamillo created a brand new story for young readers that works very well. I consider this one of the best Mercy Watson books, alongside Mercy Watson Fights Crime.