“Mercy Watson Fights Crime” is book number three in the Mercy Watson series by Kate diCamillo, first published 2006. This series is beautifully illustrated by Chris Van Dusen.

SETTING OF MERCY WATSON FIGHTS CRIME

Where in America is this series set? Based only on fictional representations, this feels Southern to me. (Do Americans get that? I have to guess.)

ERA

This is archetypal, mythical 1950s America, in which happiness consists of a wife at home wearing an apron making everyone lots of delicious food. The houses are large, the gardens manicured.

What do I mean by ‘archetypal, mythical 1950s’? Picture books are not exact depictions of real homes. When it comes to picture books, illustrations will likely include:

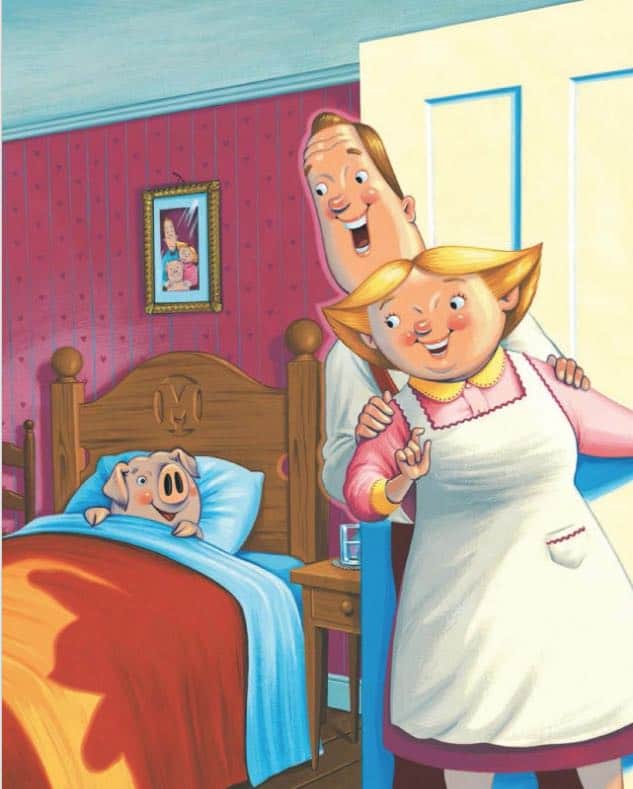

- wooden beds with sturdy bed beads and foot boards

- a chair in the bedroom

- a glass of water next to the bed, and a conically shaped bedside lamp

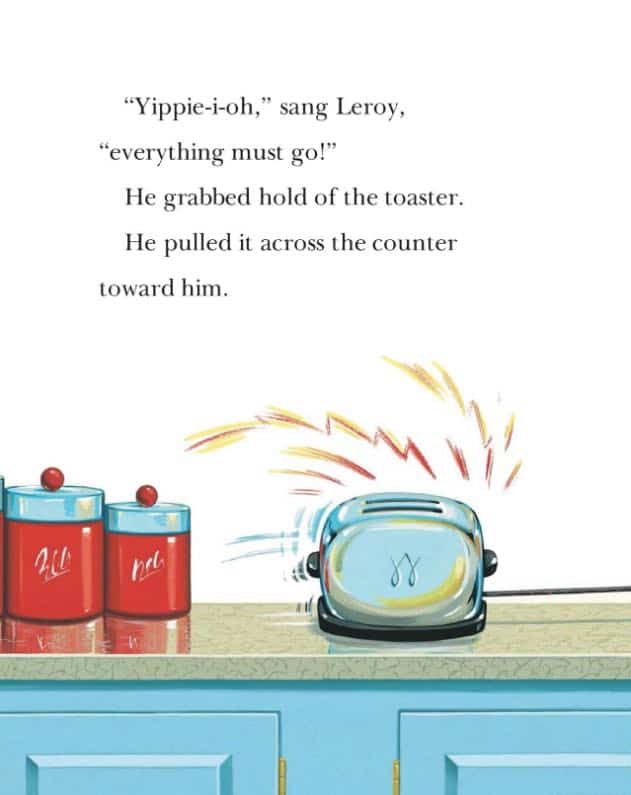

- a large, warm kitchen with 1950s appliances (e.g. the chrome toaster, which has since come back into fashion, but has a retro feel)

It has become clear in 2019, with the publication of Mercy’s origin story, that this is not literally 1950s America. Chris Van Dusen was charged with the task of drawing a cute, young, highly loveable pig, and in one interview admits that he initially forgot to age-down Mr and Mrs Watson. He subsequently put sideburns on Mr Watson and gave Mrs Watson a fringe. This suggests it was the 1970s when Mercy was young, which actually makes this 1980s America. (How long do pigs live? This is getting depressing… Okay, I looked it up: 15-20 years. Could be the 1990s.)

Apart from all that, the following image is reminiscent of American TV shows from the 1950s and 60s, which made use of split screen. We rarely see split screen used today unless the filmmaker is deliberately evoking a mid-20th century vibe. (More correctly, the split screen has evolved. You could say we’re living in the age of the split screen — so often we are watching TV while simultaneously on the Internet.)

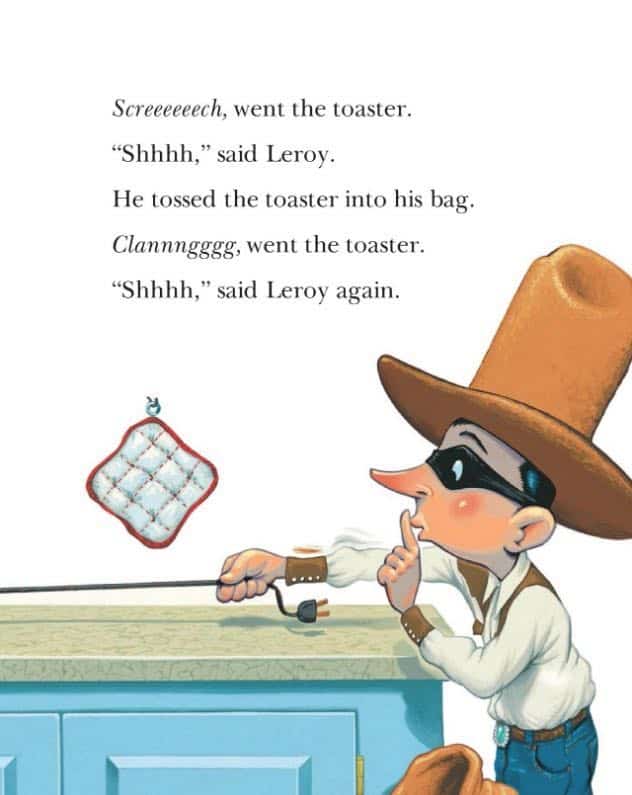

Even the cartoon convention of ‘screech’ zig-zags emerging from the toaster is reminiscent of Superhero comics from the Cold War era.

A GENUINE UTOPIA

Even in a genuine utopia, something exciting must happen. The storyteller’s challenge is to create the frisson of excitement while preserving the cosy, safe environment.

How does Kate diCamillo achieve that? First, she opens with a cosy goodnight scene. You can’t get much more reassuring than this:

Mr. Watson and Mrs. Watson have a pig named Mercy.

the opening to Mercy Watson Fights Crime

Each night, they sing the pig to sleep.

Then they go to bed.

“Good night, my dear,” says Mr. Watson.

“Good night, my darling,” says Mrs. Watson.

“Oink,” says Mercy.

Chris Van Dusen’s illustration reinforces the love that the Watsons feel for their pig — they’ve even had Mercy’s initial inscribed into her bed head. But look again. Look at the shadows. You could argue that, well, of course the shadows must be there — if the illustration contains a light source, then there must be shadows. But every single thing in an illustration is on purpose. Nothing existed here before the blank page. That strong shadow which falls across the bed? That’s ‘The Other Parents’ a la Coraline. A shadow that strong and defined gives the illustration an exciting, menacing vibe. Van Dusen could easily have made that bedspread light orange and it would’ve looked fine. The addition of that shadow is a master stroke.

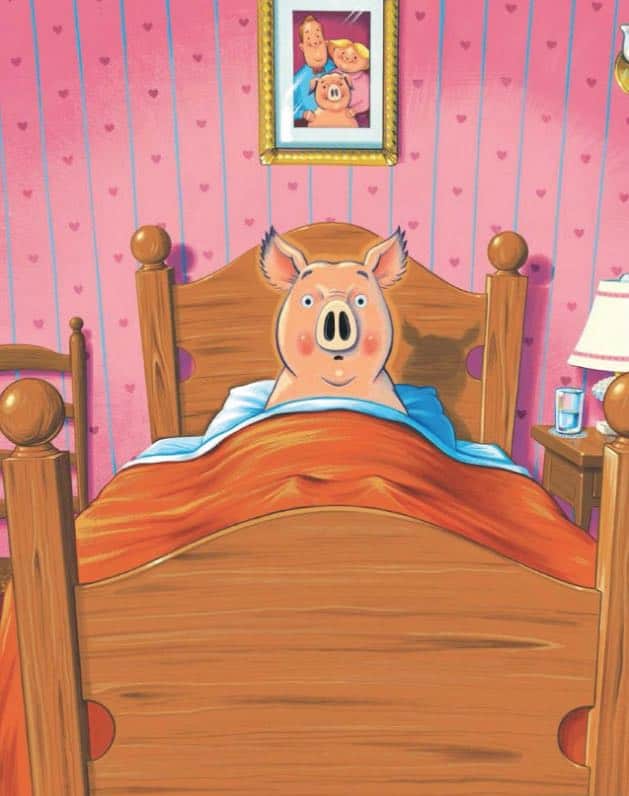

Compare with the next bedroom scene — a simple one-point perspective, which is a useful layout when the illustrator wants to avoid any scary art noir associations. In the illustration below, Mercy has heard a noise from downstairs. She’s not scared at all because she hears the toaster screech and thinks someone is making toast.

Notice how Van Dusen has avoided casting the bedroom in darkness. Yet no one has switched the light on. The brightly-lit bedroom is an outworking of Mercy’s state of mind ie. not worried one bit. And if Mercy’s not worried, readers needn’t worry either.

The shadow which does exist is of Mercy’s own head —comical rather than menacing.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MERCY WATSON FIGHTS CRIME

Marketing copy centers Opponent Leroy Ninker as the main character, with lots of fun onomatopoeia:

Leroy Ninker is a small man with a big dream: he wants to be a cowboy. But for now he’s just a thief. In fact, Leroy is robbing the Watsons’ kitchen right this minute! As he drags the toaster across the counter—screeeeeech—and drops it into his bag—clannngggg—little does he know that a certain large pig who loves toast with a great deal of butter is stirring from sleep. Soon a comedy of errors (not to mention the buttery sweets in his pocket) will lead this little man on the wild and raucous rodeo ride he’s always dreamed of!

from the Teacher’s Guide issued by Candlewick Press

I believe Leroy is the main character of this story, so will break down the structure accordingly. This is also a carnivalesque story, which has its own specific structure.

SHORTCOMING

Importantly, Leroy is not very smart. (Not sure how much he thinks toasters fetch on the black market.)

He personifies objects and can’t work out how to get out of the house without disturbing a sleeping pig. More than that, he’s burgling someone’s house and doesn’t seem to realise he should leave the scene afterwards rather than ride around on a pig!

Leroy is also endearing because of his imaginative capacity. While riding Mercy, we are told he imagines riding a dangerous bucking horse. He’s a Walter Mitty character — harmless, with big ideas about himself. This ability to sink into a paracosm is also his downfall.

DESIRE

Ostensibly, Leroy wants to steal items from other people’s houses. This is the outworking of a deeper desire, which is to imagine himself a fearsome, respected and tough bandit, reminiscent of the fantasy of the Wild West.

OPPONENT

Let’s consider Leroy as Opponent here for a moment.

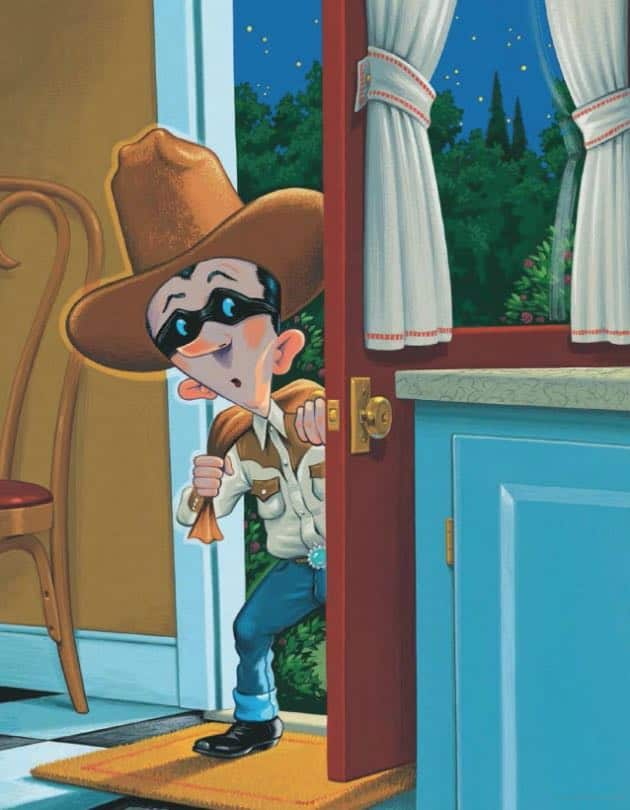

Leroy Ninker is introduced in an ominously tinted scene. This is the archetypal robber, with the eye mask, the sack flung over his back. These would make him generic, much like the robbers in Walter The Farting Dog, in which generic robbers are useful. But diCamillo is turning the robber himself into a comedic character, and a comedic character requires a distinguishing feature or two. Kate diCamillo has made use of a mash-up of archetypes to arrive at a unique man:

- archetypal robber

- archetypal child who wants to grow up to be a cowboy.

Leroy is basically a Cat In The Hat character, who turns up when he isn’t meant to and wreaks havoc. While wreaking havoc, the child viewpoint character (Mercy) has a lot of fun.

Before she lets Mercy have fun, diCamillo reveals Leroy as an unthreatening character, despite his sticky fingered ways. He contains several layers of comic irony:

- A small man with a big hat (in which the hat symbolises his self-importance)

- He makes plenty of noise himself while telling the toaster to be quiet

- He has sticky fingers both literally and metaphorically, because his favourite food is butterscotch.

But what about the enduring opponent of Eugenia Lincoln next door? It’s a rule of this setting that the sisters must appear at one point, in which the narration switches point of view. It’s also necessary for the plot to work, because Leroy turns out to be Mercy’s comrade in fun.

PLAN

Leroy will break into Mercy’s house and see if he can get away with stealing things. He will wear his cowboy costume because this is basically cosplay.

His Plan looks set to fail when Mercy trots downstairs thinking someone is making toast. Instead, expectations are foiled, because Mercy doesn’t realise this guy is a burglar. How does diCamillo turn this into a comedic situation? First there’s the comedic obliviousness — characters who don’t realise what we realise are always laughable (dramatic irony). But on top of that, diCamillo slows the pacing right down. Narratologists would say the story is set to ‘pause’.

One way a writer can achieve that is by saying what is not happening. This was pointed out to by by Jane Alison in her book Meander, Spiral, Explode. Mercy sees that there is no toaster, no bread and no butter. But she wholly fails to see what IS there; she is single-mindedly fixated on buttered toast.

BIG STRUGGLE

In a carnivalesque story, the ‘Battle’ is an episode of extreme fun. Here it is the comedic sight of a tiny bandit cowboy riding a pig, all the while thinking he’s an actual cowboy.

Comedy is heightened when we are shown other characters enjoying the spectacle with us. Eugenia and Baby come in handy for that — they are functioning not so much as Opponents but as the two old men from The Muppet Show who make sardonic comments about everyone else in their vicinity.

ANAGNORISIS

The characters experience no anagnorisis because this is a comedic story in which the characters remain less knowledgeable about their situation than the readers, who have seen a broader picture. We’ve seen Mercy going to bed, the inside of Eugenia and Baby’s home, the arrival of the robber and the conversations between the police officers. This is true omniscient narration, and keeps the reader in audience superior position, feeling smart.

The revelation is simply a conclusion of fun. If we haven’t realised immediately we now know that Leroy’s penchant for butterscotch is going to be his downfall, because Mercy will accost him for it. Significantly, diCamillo made sure to ‘casually’ mention (twice) that Leroy enjoys butterscotch. (I was very slow on the uptake and didn’t even connect butterscotch sweets to Mercy’s love of buttered toast.) By the time we see Mercy on top of Leroy we’re wondering what she’s after. Then all is revealed: She’s sniffed out the treats!

NEW SITUATION

We might assume Leroy is taken to prison, though subsequent tales in the off-shoot series reveal that Leroy finds gainful employ at the cinema. The rule of this series is that everyone sits down to enjoy buttered toast. Order has been restored.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Some people enjoy wine and food pairing — I enjoy pairing children’s stories with stories for adults. Compare Mercy Watson Fights Crime with “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” by John Cheever.

FURTHER READING

THEFTS from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.