**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

Have you ever showed up to extend care to a loved one in their time of need, but in an uncomfortable reversal, the object of your care has made herself busy taking care of everyone else instead? “Memorial” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. Find it in Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You (1974).

ALICE MUNRO’S FICTIONAL CAREGIVERS

- “The Peace of Utrecht“

- “Images“

- “Memorial”

- “The Ottawa Valley”

- “Winter Wind“

- “Spelling”

- “Friend of My Youth”

- “Wigtime“

- “Accident”

- “Chaddleleys and Flemings: Connection”

- “Family Furnishings”

- “Soon”

- “The Ticket”

SETTING OF “MEMORIAL”

Alice Munro lived for a short time at Kitsilano Beach in Vancouver as a 20-year-old newlywed. That was 1952.

Although the author is best-known for her smalltown Ontario settings, the occasional story is set in Vancouver. “Memorial” is set in a wealthy part of West Vancouver.

In this story, too, I feel that a ‘natural-born’ Ontario woman is reluctantly in Vancouver, where she is surrounded by a completely different culture.

An Australian woman from Wagga Wagga New South Wales visits her sister in the inner-suburbs Melbourne. A New Zealand woman from Ashburton visits her sister who now lives on Auckland’s North Shore. An American woman from a small town just outside Seattle visits her sister who now lives in a wealthy part of Los Angeles. An English woman from Chipping-Warden visits her sister who now lives in London’s West Hampstead… Imperfect analogies aside, you don’t have to leave your own country to experience culture shock. Sometimes, you don’t need to leave your own family. Sisters grow up in the same place, then go on to lead very different lives.

As do best friends. Alice Munro’s “Wigtime” is another, similar example of how two girls growing up in very similar circumstances lead vastly different lives as adults.

“MEMORIAL” IN A NUTSHELL

A sister flies to Vancouver, to her younger sister. The sister has recently lost her 17-old-son in a car crash. The two women are very different. June, who has lost the son, is wealthy and super organised. Eileen is more observant, well-read, and more reminiscent of Alice Munro’s woman characters who live in smalltown Ontario. Eileen makes a good viewpoint character, wandering around the sister’s wealthy, hippie house during the function that takes place after the Memorial Service.

After the memorial party, Eileen has sex with her brother-in-law, feels a bit awkward and flies home earlier than planned.

CLOSE READING OF “MEMORIAL”

Eileen and June are sisters in their late 30s or 40s. June is the younger sister.

Whereas Eileen has so-far led a slightly chaotic life, though not atypical in its disorganised chaos, June’s life has been more ordered and extraordinary. June married a man with significant inherited wealth and does everything Properly.

The wealthy couple live a privileged lifestyle in which neither of them has to work for money. June and Ewart had three children together than adopted two young Indian girls. (I’m not sure, reading this 1970s story, what is meant by ‘Indian’. Indigenous peoples?)

DEPICTING CHARACTER IN A SINGLE SCENE

June does nothing by half measures. Alice Munro evinces this aspect of June’s temperament by opening with how she buys and makes coffee: She would never buy instant. This is a woman who grinds her own beans.

June grinds her own blend from a various carefully selected growers in a grinding machine which has, in turn, been very carefully selected after reading Consumer Reports. Even after reading the consumer report though, she’s still unhappy with her choice, regretting that she didn’t buy a bigger model.

THE GREAT CAREFULNESS DIVIDE

This short story is about caregiving, but it’s also about carefulness.

June is trained in psychology. This training reveals itself in ways Eileen finds quite irritating. Junes knows words to describe people, or thinks she does. Therapy speak entered the common lexicon in the 1970s, and Alice shows us how here. We are currently going through another cultural moment in which various therapy terms are being used — and misused — by people who have no psychology training, but are hearing various words bandied about. ‘Gaslighting’ is one. ‘Narcisissm’ is another. ‘Pyschopath’ yet another. (I’m not trained in psychology myself, so have gone out of my way to learn what these concepts mean.) The good news is, podcasts by psychologists are hugely clarifying.

What was the 1970s version of Therapy Speak? Note that June is into Gestalt Therapy, a mode which emphasises personal responsibility before change can be made. She has also learned Yoga, and attended Growth Groups (one of which Eileen has trouble taking seriously).

In the 1970s, people were talking about:

- repression (from Freud)

- ‘working things through’ so as to be done with them (ostensibly)

Basically, there’s a deep temperamental difference between the two sisters: Eileen is laid back and takes things as they come whereas June is the super-organised type who becomes easily stressed out when things are not in perfect order. This affects every aspect of life, down to the organisation of a drawer. Moreover, June believes her own way of doing things is the Correct Way of doing things.

As one of the Eileens of the world, I definitely recognise the sort of person who justifies their own method by saying, “It takes less time in the end.”*

*It does not take less time. It simply feels like it takes less time because you’re doing it in smaller chunks, which in turns means your head is full up with tidying and organisation, constantly.

NOT EVERYTHING CAN BE CONTROLLED

But now, June and Ewart’s seventeen-year-old son, Douglas, has been killed in a car accident. Three other boys in the care were mostly unharmed. For all June’s care and organisation, she was not able to organise this one. This tragedy will be the ultimate test for a super-mother.

Eileen has flown in to stay with June’s family in the house. She plans to attend her nephew’s memorial service and to look after her grieving sister.

In psychology, when you attempt to control something that is ultimately uncontrollable, we call it “misapplied control.”

Because control is effective in so many situations, we can apply it in places where it doesn’t work.

However, no amount of planning can eliminate all risk. If you can’t tolerate uncertainty, you can end up fixated on trying to control what is fundamentally uncontrollable.

Attempts at control fall into two broad categories: external and internal. When faced with uncertainty, we try to manage our fears by taking external action or by trying to control our internal state.

The Paradox of Control, Every.to

ONE WAY OF DEALING WITH GRIEF: KEEP YOUR HEAD FULL OF WORKADAY THINGS

But June is dealing with her loss by keeping herself extra busy, and doesn’t seem to need any practical help from Eileen.

We have already seen how Alice Munro wrote the coffee scene at the opening of the story to illuminate the difference between these sisters. We don’t yet have any context, but it is June who brings Eileen a coffee in bed. Eileen meant to do this for her grieving sister, but made the error of assuming that June would prefer not to be woken so early. June tells Eileen that she wouldn’t have been able to manage the workings of the coffee grinder anyway, which establishes a mild passive-aggressiveness into an otherwise cosy scenario.

As the day progresses, Eileen watches her sister in action and grows increasingly unnerved by her sisters’ lack of display of weakness or grief. June hasn’t slowed down at all. She was up before dawn, got the younger kids ready for school, and next she’s on the phone, organising how various community members will be making their way to the Memorial Service…

EWART

Ewart, Eileen’s brother-in-law, is a little more obvious in his quiet grief. He shows Eileen around his carefully planned Japanese garden. Like June, Ewart is very careful in everything he does. He has accrued much knowledge about various topics, becoming expert in many areas. Eileen interprets this as a way of dealing with the lack of purpose which may otherwise come with significant inherited fortune.

‘SEXUALLY UNATTRACTIVE’ (WRITERS HAVE LONG DIVIDED ATTRACTION INTO DIFFERENT PARTS)

Eileen finds Ewart ‘sexually unattractive’ — an interesting phrasing which evinces how someone can be attractive in some ways but not in others. The ace community talks a lot about this and call it the Split Attraction Model (the SAM) — a contentious model, not least because it doesn’t hold water as a scientific model.

Still, the so-called Split Attraction Model remains a useful concept for many people when explaining how their own attraction works. Attraction comes in many forms. Other instances where literature touches on this:

Not that she was striking; not beautiful at all; there was nothing picturesque about her; she never said anything specially clever; there she was, however; there she was.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Me, she said. You see me as a full human being. That’s why you’re not attracted to me.

Sally Rooney, “At The Clinic“

Yes I am.

Sexually, but not romantically.

(the story which led to Normal People).

Note that even within individuals, each of the different attractions listed by the SAM can vary widely. Attraction is not necessarily static across a lifespan:

- Aesthetic attraction: Finding someone beautiful

- Sexual attraction: Feeling the desire to have sex with someone (sometimes called ‘physical attraction’)

- Romantic attraction: Difficult to define, since romance is partly culturally scripted. Romantic attraction can be guided by sexual and aesthetic attraction, but not always, and not in everybody. (This is perhaps the most problematic axis of the split attraction model. Romantic attraction is infamously difficult to define. Not only that, notions of romance vary across time and culture.)

- Touch attraction: not a desire to have sex, but a desire to be close in other physical ways (also called ‘sensual attraction’)

- Emotional attraction: Feeling deep care for somebody

- Protective attraction: Attraction to those in your care e.g. children, pets

- Social attraction: Wanting to be around someone

Is Eileen attracted to her brother-in-law in any of these ways? It would seem she admires his knowledge and has a sophisticated understanding of his psyche. Perhaps Eileen’s understanding of Ewart is even deeper than June’s, despite June’s being married to the man, and also having the psychology degree. While June busies her mind with tasks such as the organisation of drawers, Eileen is an observer of human nature.

EILEEN AT THE MEMORIAL ‘PARTY’

Skipping over the service, Alice Munro takes us to the service, which the (close-to Eileen, third-person narrator originally calls a ‘party’, though Eileen later acknowledges that this is not a party at all).

The memorial function takes place at the house, populated by teenagers and neighbours, children and friends. Like other stories in this collection, Alice Munro describes a hippie milieu specific to the 1970s. She has shown us various iterations of hippie culture in stories such as “Walking on Water” and “Forgiveness in Families“; in this narrative she explores the wealthy, middle-aged version and their teenage children.

THE RICH-MAN NEIGHBOUR

At the after-service gathering, Eileen strikes up conversation with a neighbour man who moved to this wealthy West Vancouver suburb from North Vancouver. She notices how wealthy people have a certain way about them:

Like many rich people he seemed to be full of a sincere and puzzled, almost heavy-hearted, hope that he had got what he should.

“Memorial”

Additionally, many women will find Eileen’s gendered observation resonates:

“Always like views?” he repeated, and showed by his bent head, his tolerant eyebrows, that he was waiting to be charmed.

“Memorial”

Eileen is a little disinhibited because she’s had a few drinks, and suggests to the wealthy man that he may sometimes feel guilty for failing to appreciate the beautiful view from his beautiful house.

EILEEN WANDERS AROUND THE HOUSE

Reminiscent of how the young housemaid moves through a wealthy house during a party in an earlier Munro story called “Sunday Afternoon“, Eileen pours herself a fresh drink and wanders around the house as our viewpoint character. She comes to where the children are playing Fish, the card game.

Beyond feeling ‘intimidated by the Indian children’ in June’s presence, why might Eileen feel discomfort about her sister’s two adopted girls? Perhaps Eileen sees adoption from a disadvantaged minority as a white-lady performance, or perhaps she sees it as the ultimate example of cultural theft. (Or perhaps this is my own 2020s reading.)

ALICE MUNRO AND ELIZABETH STROUT

The book that had the greatest influence on my writing

The Guardian interview with Elizabeth Strout

The Collected Stories of William Trevor. I credit him with a great deal of my ability to find my way around a sentence. What a writer he was; he could flip over a sentence so gently, and show the underbelly in a heartbeat. His work is always quietly compassionate. Also the work of Alice Munro has influenced me. Munro and Trevor have been like two bookends in my writing life.

In a scene reminiscent of Olive Kitteridge at her son’s wedding (cf. the novel Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout), Eileen is soon exhausted by this gathering finds a room in this expansive house to shut the door and lie down.

There are various similarities between Olive Kitteridge and Eileen in this Munro short story: Both are in an environment where they feel out of place in comparison to family members from a different economic strata. Olive’s son Christopher is marrying Suzanne, a much wealthier, more highly educated young woman.

FLASHBACK TO THE DEATH OF THE SISTERS’ FATHER

While lying down, Eileen recalls when news of their father’s death arrived. He had been killed in the war.

Speaking of Therapy Speak gone mainstream, the description of the mother does, in fact, sound exactly like how Dr Ramani describes vulnerable (covert) narcissism:

Their mother who was most of the time a dangerous person, full of myserious hurts, unnameable grievances, seemed to have abandoned her usual person, to have turned neutral, undemanding, and, of all things, shy.

“Memorial”

In a story titled “Memorial”, we can extrapolate the Latin memoria and consider the various related English words, namely ‘memory’. This is a story about how people variously interpret memory as much as it is about remembering and honouring the recently deceased. (Now obsolete, ‘memorial’ used to mean ‘memory; recollection.)

FLASHBACK TO THE AFTERNOON’S MEMORIAL SERVICE

Now for a much more recent flashback.

Still lying down, Eileen considers the Memorial Service, in which someone gave a reading from Kahil Gibran’s The Prophet. This work is exactly 100 years old in 2023, and you can read it online at Project Gutenberg since it’s out of copyright. If you take a quick squiz you’ll see how a snippet read at a Memorial Service could easily sound pretentious, especially out of context.

Eileen considers it inappropriate, and is suspicious of the ‘fraud’ at her sister’s house:

- The fake nice-ness

- The fake happiness, the business-as-usual mentality

- The perfect coffee, the perfect house, the perfect garden

- The house full of people who may or may not have been Douglas’s friends

- Her sister’s choice of eye-shadow

- The memory of how, speaking once about their problematic mother, June insisted she’d worked through all her issues in Gestalt Therapy and was completely ‘finished with it’.

- The choice of reading at the service

Still, Munro manages to create in Eileen who does not feel superior to her sister because of this feeling of fakeness. Eileen acknowledges she is herself living in her own version of unreality:

As for Eileen, she has read a great deal, and knows how to be offended by all kinds of cheapness […] The only thing that we can hope for is that we lapse now and then into reality, thinks Eileen, and falls asleep for a few seconds, to wake up scared, fingers tightening on the glass.

“Memorial”

EILEEN AND EWART IN THE GARDEN OF EVIL

Before, when Eileen and Ewart wandered around the Japanese garden, Eileen noted how she did not find her brother-in-law sexually attractive. But now they are both drunk, June is out of the way (having taken two sleeping tablets), and it is night-time.

Ewart is outside watering plants, Eileen is getting some fresh air. They encounter each other and it no longer matters that the attraction isn’t sexual. Alice Munro makes an excellent job of conveying how a thoughtful, observant character like Eileen finds herself having sex with her sister’s husband.

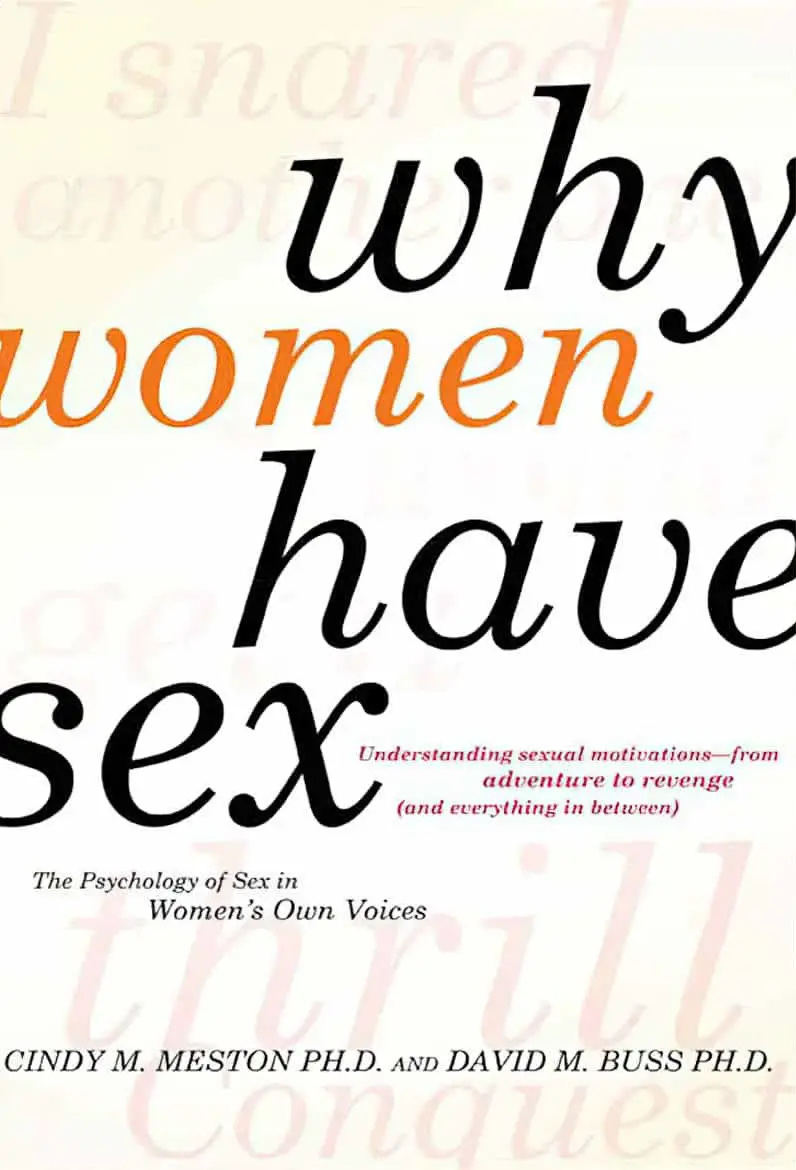

Also of interest: Episode 50: How Many Reasons Are There To Have Sex? At Least 237 of Justin Lehmiller’s Sex and Psychology podcast, which goes into the many reasons why people have sex. It’s not always to do with sexual attraction. People have sex for many reasons. This episode focuses on why women have sex, as he speaks to the author the book Why Women Have Sex: Understanding Motivations from Adventure to Revenge (and Everything in Between).

Meston and Buss reveal the motivations that guide women’s sexual decisions and explain the deep-seated psychology and biology that often unwittingly drive women’s desires–sometimes in pursuit of health or pleasure, or sometimes for darker, disturbing reasons that a woman may not fully recognize.

Why Women Have Sex uncovers an amazingly complex and nuanced portrait of female sexuality.

- sex as a defensive tactic against a mate’s infidelity (protection)

- to boost self-confidence (status)

- as a barter for gifts or household chores (resource acquisition)

- as a cure for a migraine headache (medication)

- etc.

How might a psychologist explain why Eileen acquiesces to Ewart? Munro has already established that Eileen does not find him sexually attractive. We know from the asexual community that attraction is not the only reason why people may choose to have sex. Aside from the liquor, what forces are at play?

Something to do with care, I feel. June has been unreachable as a receptacle for Eileen’s offer of care, and now she drunkenly allows her caregiving to fall in Ewart’s direction. After all, women are acculturated into caring for men. Women caring for other adult women, especially the able-bodied, is a much more difficult dynamic. And that’s where the backstory involving the mother comes in. Neither of these women is likely to feel easy around a grown adult female relative, probably because of the dynamic which was established long ago by the narcissistic mother.

Do you agree with Eileen that Ewart is craving the opposite of his wife as a way of dealing with immense loss? Is Eileen the ‘brief restorative dip’?

JUNE’S REVELATION

Eileen flies home early, having betrayed her sister. Packing to leave, she finally gets something real from her sister, who reveals that her son wasn’t killed by the car crash itself, but was instead crushed afterwards, having escaped unharmed from the car. The car had been on its side, then toppled onto him.

Of course, this must be symbolic for the sisters. We have two events mirrored. In the same way, June and Eileen’s sisterly relationship has ‘toppled’ not due to the horrific event itself, but because of what happened in its wake.

Eileen asks June how she knows about this. June had been told by one of the mothers, whose son was also in the car crash. When Eileen responds that such information cannot be a kindness, we know she is thinking about what she, herself, might reveal at this moment.

Readers might extrapolate that the sisters’ relationship will never be quite the same again. We can also deduce that Eileen will never tell June that she had sad garden sex with Ewart, because she would consider this an unkindness.

Also, we’ve gotten to know the two women by now. Whereas June likes ‘completeness’, whether that be in her organising of drawers or organisation of an event, or talking things through in therapy, Eileen is able to sit with messiness. Not everything needs to be ‘worked through’, she understands.

So in fact, the sisterly relationship could go bad, or (assuming Ewart keeps quiet) their already slightly-distant relationship might remain the same, precisely because of Eileen’s ability to sit with untidiness in all its various forms.