melodrama is a widely misunderstood term but has its place in good storytelling. What is melodrama, and how do we write it?

Melodrama In Everyday Usage

In everyday English, if we describe a person as ‘melodramatic’ we are probably describing a high drama individual.

We’re probably talking about what we consider ‘too much emotion’. When talking about storytelling, though, melodrama is a legitimate, widely-enjoyed art form with a long, successful history. There’s no inherent pejorative meaning in the terminology ‘melodrama’.

A Brief History Of Melodrama

THE BEGINNING OF CAPITALISM

Melodrama emerged around the time of the French Revolution, which marks the beginning of capitalism and a shift towards commodification. Societies were moving from mercantile to market based economies.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Commodification had special relevance to women, because women were themselves commodities. Women and girls were married off for their family’s gain, with no autonomy. In the early modern era, women were not legal individuals, subsumed first by their fathers, next by their husbands.

THEMES TAILORED TO WOMEN

Melodramatic stories are about what happens to an individual when they are faced with a difficult circumstance. Early melodramas asked questions such as, What is it like to be married off to a man you don’t know or like? Things happened to these main characters. In real life as in melodramatic fiction, these main characters had little agency. Pride and Prejudice is classic melodrama.

MELODRAMA AND THE GOTHIC TRADITION

Like gothic fiction, melodrama has always been a popular form of storytelling rather than considered high art. No coincidence there: both types of story are about and enjoyed by women, and whatever concerns women is historically considered niche and frivolous.

MELODRAMA AND MUSIC

In earlier times, melodramatic stories were interspersed with musical numbers, though didn’t quite fit the definition of musical theatre. This convention affected how melodramatic works were plotted; with more airtime taken up by the music, there was less time available for the main narrative. When storytellers are faced with telling a story in a very limited time, they have no choice but to rely on character archetypes and plot tropes. Audiences are already familiar with these things and need nothing by way of introduction.

For this same reason, the first cinematic productions also relied on melodrama. With no words in the silent era of film, anything other than reliance upon archetype was impossible.

THE 1940S

The 1940s required stories that appealed to women, so stories emerged around the different and proper roles of women in society.

SOAP OPERA

The 20th century gave us the soap opera, a low form of melodrama. They’re not functioning as true melodramas, though. There’s a reason soap operas are shown in the middle of the day — audiences are not craving genuine emotion at that time of day. If soap operas are melodramatic, it’s because they are designed to be an emotional diversion, not a catharsis.

THE 2000S

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the way television series are funded. The makers of TV rarely know how many seasons they will be funded for. If they don’t know how long they will have to complete a story, they have no choice but to move away from the quest narrative, in which the story is over once the quest has been achieved. Instead, writers create a large cast of characters and move the camera between characters, between families, setting up a highly unusual situation and then letting the audience watch individuals’ responses to that situation by way of exposing different moralities. That’s what melodrama is.

PRESTIGE TV

Not all ‘prestige (episodic) TV’ is melodramatic. Breaking Bad is more quest than melodrama. The writers have previously spoken about one of the most challenging tasks of writing Breaking Bad: The cast of characters is very small, not to mention the writers’ strike that happened part way through season one and never knowing from season to season whether the show would be renewed. (Given the challenges around bringing that story to screen, they did a fantastic job.)

The Sopranos sits further toward the melodramatic end of the scale. The cast of characters is much larger. This is a violent, gangster world, so highly unusual (and shocking) events happen on the regular. Characters respond to that event in various ways.

Big Love, Six Feet Under and The Handmaid’s Tale are melodramas. Each of those shows places main characters in a very difficult, impossible situation. Due to their entrapped status, autonomy of the main characters is limited.

Desperate Housewives is perhaps what many people think of when they think ‘melodrama’. In fact, Desperate Housewives is a satire of soap opera (and wasn’t sold until ‘satire’ was inserted into the pitch).

MELODRAMA AND YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE

Young adult stories with a mainly female audience are often described as ‘melodramatic’, with melodrama used as a pejorative. For instance, Rotten Tomatoes says of the film adaptation of If I Stay, “Although Chloë Grace Moretz gives it her all and the story adds an intriguing supernatural twist to its melodramatic young adult framework, If I Stay is ultimately more manipulative than moving.”

Melodrama and Surrealism

In everyday English, ‘melodrama’ suffers from the same problem as ‘surreal‘. Generally, speakers use both of these words to describe something that is not realistic or unreal, when in fact the terms properly describe works of art which are more real(istic) than other works of art.

Surrealism and melodrama are related. Surrealism is a different but related kind of exaggeration. The meanings implicit in objects, people, or events become more obvious and accessible than meanings normally are in the chaotic muddle of our everyday world.

Because of its heightened, exaggerated reality, melodrama lends itself easily to symbolism, allegory, and surrealism.

How Is Melodrama Different From Drama?

Melodrama is the technique of revealing reality by concentrating on the remarkable rather than the ordinary. Melodrama is about extremes, especially extremes of circumstance and emotional reaction to that circumstance.

Melodrama is a storytelling paradigm rather than a genre. For that reason, different genres, and different stories within those genres, each have their own analogue switch relating to melodrama. Some genres tend to be more melodramatic than others. If we consider war movies a genre (they’re actually a blend of action and drama in a wartime setting), then some war movies are melodramatic (Hurt Locker), but some are quest stories instead (Saving Private Ryan, Apocalypse Now).

Many stories aimed at children (especially teens) are high in melodrama.

We might think of melodrama as the inverse of ‘quest’ arc. This is a continuum rather than a binary division. Some stories are more quest-like, some stories are more melodramatic.

When determining the extent of melodrama in any given story, ask the following: Is there a strong moral question that drives the story? Melodrama is about groups of people (families and family stand-ins), and how massive, unusual outside forces change interpersonal dynamics.

Melodrama is not about twists and turns. Melodrama won’t be using many of the techniques required by, say, thriller, which aims for suspense and perhaps for horripilation but avoids pathos.

What is melodrama for?

- Melodrama rouses strong emotions in its audience. These are stories which intend to invoke pathos. Storytellers want to make you cry. First they make you identify with their characters, then they put them through the mill.

- Melodrama invokes implicit shared attitudes.

- Melodrama presents a cast of characters — typically a family, or family stand-in — gives them an impossible dilemma and then shows how each of those individuals respond to it. Melodramatic stories are therefore domestic in nature. Also, by definition, melodrama requires a clear moral dilemma. A melodramatic story asks the audience to consider what they might do in the same situation, and to ask big, psychological questions such as, How much am I prepared to endure? How much am I prepared to risk? Am I seeing the situation correctly? Is it me that’s the problem here, or is it the world?

Pejoratively, melodrama refers to stories in which the writer tries to make the reader feel something but overdoes it and thus fails. This isn’t entirely fair use, because sometimes the writer WANTS the audience to enjoy the spectacle of characters getting all emotional without involving the audience in the drama. Melodrama can be harnessed deliberately in order to let an audience enjoy a story in a different way (from straight drama).

Why Write Melodrama ?

Sometimes visionary, heightened reality is the most real of all, because all the transitory, trivial details have been stripped away to reveal the fundamental essence of things.

The Setting Of Melodramas

Melodramas make their heroes pawns in cities which symbolise the originating problem for the hero rather than the end of the hero’s activity. The hero is a conscious agent and a conflict between morality and the violation of established laws is developed.

Symbolism.org

A feature of melodramatic settings is often darkness contrasted with light. A lot of the scenes will probably take place at night.

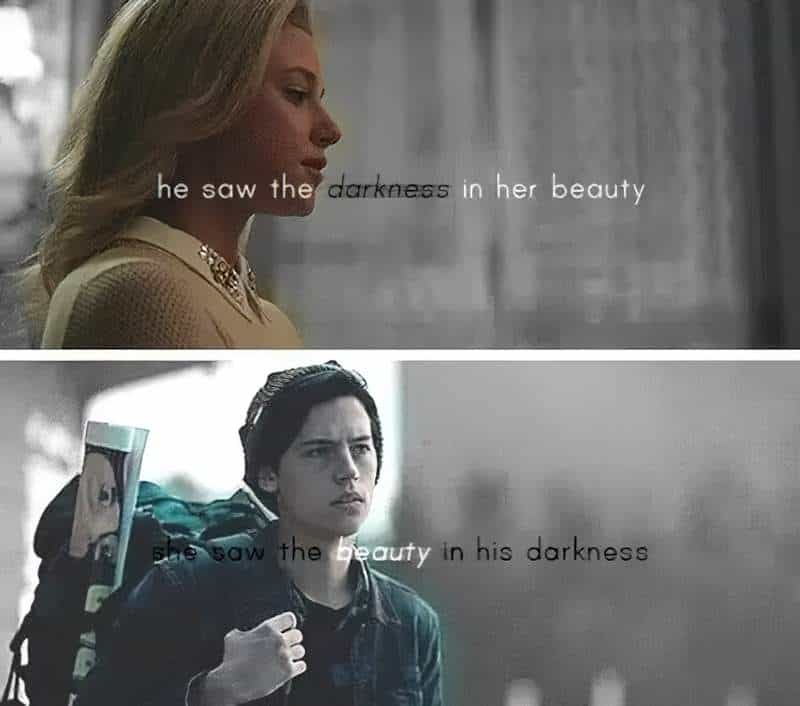

Use of colour palette in the melodramatic TV series Riverdale promotional material makes the most of this contrast:

The dark/light thing is incorporated into the character building, as shown by the taglines of Riverdale below:

Desire and Need In Main Characters of Melodramas

In traditional (quest) stories, people tend to rise to a challenge in a superhero kind of way. In real life, people are mostly victims of circumstance. Since melodrama is ‘realistic’, it goes for ‘victims of circumstance’ characterisation.

People working in film and TV (and less so in children’s literature) are told constantly that their characters require a desire (surface and underlying), and a shortcoming/need (moral and psychological). Next they’ll need to make a plan, then keep changing the plan as things go wrong for them.

These elements are present in almost all compelling stories, but because writers are told they must have them, this creates a loop in which other types of stories don’t get made.

In real life, there are people who don’t have much agency. That describes all of us at some point of other; something big happens to us and we had no say in the matter. That gives us more in common with the romantic hero than with Walter White, whose plan is to cook meth and provide for his family. The melodramatic main character does not start out with a strong desire. They may wish to simply keep going in their highly restrictive lives. They may not have the executive functioning required to make plans (this is especially true of child characters). They may not have the freedom of gender, or of race.

In melodrama desires are muted; plans are reactionary. I’ve seen the term ‘out-of-whack’ event used to describe the external force that kicks off the melodrama:

Out-of-whack event. In Aristotelian drama, the story concerns a character whose stable life is knocked out of whack by an external force. The remainder of the story concerns his attempts to put his life back into whack, and his success or failure. The out-of-whack event inaugurates the struggle.

Commonly the out-of-whack event occurs at the novel’s opening (e.g. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land, Valentine Michael Smith is brought to Earth; or Zelazny, Nine Princes in Amber, Corwin recovers his powers but not his memory). It may already be in the past (e.g. Silverberg, The Man in the Maze, the aliens tamper with Muller’s brain to broadcast evil emotions).

Glossary of Terms Useful When Criticising Science Fiction

(I’m also noticing that the term ‘Aristotelian Drama’ basically describes ‘melodrama’. But Aristotelian gives a story street cred, whereas the word ‘melodrama’ confers a whole lot of negative connotation based on whose stories we have historically considered worthy of telling.)

Why Do Melodramas Take Themselves So Seriously?

Comedy doesn’t lend itself to melodrama. Comedic heroes tend to be low mimetic. Comedy derives from characters’ own shortcomings — they don’t know enough, they are full of hubris, they are always making mistakes. But comedic main characters have drive, they make plans. Terrible plans, but plans nonetheless. Comedy evokes laughter; melodrama evokes tears. Melodrama goes deeper into character than comedy, which relies on archetype, sometimes with tweaks, but archetypes as base. (This is also why Breaking Bad is less melodramatic than The Sopranos — Breaking Bad contains a lot of dark comedy, and the two don’t play well together.)

Opponents in Melodrama

In a melodrama, an event happens which robs your character of their power. Their struggle is to regain their power, and thereby achieve freedom. Whoever stands in the way of them regaining their power functions as the opponent. These opponents don’t tend to be arch nemeses and archetypal villains, but spoilt brat offspring and overprotective parents — people with their own understandable wants and needs.

The Unoriginal Plots of Melodramas

Melodrama requires a strong, tried and tested plot. That’s why melodrama tends to correlate with genre fiction.

The external events that happen in melodramas won’t be original. Audience interest derives from the characters’ various reactions to these events. Melodramatic plots are therefore routine and expected.

When plot becomes less important, character becomes more important.

Whatever happens in your melodrama, make sure it is absolutely central to the lives of your main characters. These should be people in crisis. If they’re not in crisis, you’re probably writing drama, not melodrama.

There’s nothing like impending death to rouse you from existential boredom.

Roger Ebert

Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Bridges Over Madison County is melodramatic because a woman falls in love with a man who is not her husband, in a culture where leaving her husband is not possible or okay. How does she deal with this over the course of a lifetime? She knows she’ll never love anyone like this again. The story explores how this chance encounter makes her feel, and how it makes her children feel once they discover their deceased mother’s secret life. Brief Encounter is another story with the same basic plot, yet these are clearly two very different stories. It’s not the plot that makes them different.

Young adult melodramas I Am Not Okay With This and Never Have I Ever both start with identical set ups: A teenage girl has recently lost her father. Her interiority is revealed via trips to the school counsellor, who encourages her to open up in a journal. There are other similarities because these plots are not what sets them apart; its all about the character, and these young women’s responses to the loss of their fathers.

Six Feet Under started every episode with a death, followed by the Fisher family meeting with the family to plan a funeral, more or less. The plots themselves would not have soon lost novelty if it weren’t for the highly interesting treatment of character, including dream sequences which hadn’t been seen on television before.

There are many, many stories about a city woman who faces a crisis and returns to her roots in a rural area, where she opens a café/bed and breakfast/etc, exposes a secret about her past, then meets the love of her life. Again, there is nothing unique about the plot. This opens up plenty of storytelling room to character development, crisis and… melodrama.

Notice how each of these stories listed above appeal to largely female audiences. There is a bias at work when evaluating stories from a cerebral angle: Original plots get elevated to high art, whereas varied emotional reactions in characters and audiences are criticised for being ‘tearjerkers’, lacking in originality and so on.

The Problem With Melodrama: Believability

Melodrama ignores the ordinary to concentrate on the unusual and unlikely. Ironically, it often creates a credibility problem for readers who expect mimesis in storytelling. (Many true stories are nonetheless unbelievable when transferred to the realm of fiction.)

Tips For Writing Melodrama

Tip 1: SHOW THAT THE MELODRAMATIC THING WORKS RIGHT AWAY

Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire begins with a vampire talking into a tape recorder. Either way, you know pretty clearly what you’re in for from the beginning.

Each story demonstrates its central premise: modern vampires, or shoot-’em-up spaceflight. If you’re going to write melodrama, start with melodrama.

If your story will be playing by rules other writers have used before—that vampires exist, that faster-than-light travel is possible—melodrama may be the best way to go. Work with the accepted convention. Introduce your premise with as little fuss as possible and get on with your story. Stephenie Meyer built her Twilight series on the accepted convention of vampires already established to modern readers by writers such as Anne Rice.

Tip 2: SHOW THAT THIS THING HAS WORKED IN THE RECENT PAST

Especially use this trick if you’re introducing an entirely new concept.

There’s no arguing with the past — it’s over. Use this obvious bit of wisdom to have a character talk about the thing before it actually appears. Or you can write about a past event for which no satisfactory explanation has ever been found. The story then demonstrates the cause in the present, which also explains the past, retroactively.

Tip 3: USE A TRUSTWORTHY NARRATOR OR CHARACTER

Establish a reasonable character, and have them take the curse/magic/fantasy world seriously. Don’t have anybody doubting it, at least not for long.

This particular storytelling trick doesn’t always work well with the most savvy of young readers. Here’s a young adult who recently shared with the Internet why she doesn’t like YA fiction — one of her main points is that in real life nobody listens to teenagers. The fact that fictional adults listen to fictional young characters can either be a refreshing change or it can trigger annoyance, but now at least you see why writers do it.

Most readers are used to fictional conventions and are also appreciative of new and original fantasy worlds. They will accept anything if it is introduced correctly.

Tip 4: JUXTAPOSE THE EXTRAORDINARY WITH THE MUNDANE

Surround your curse with tangible everyday objects and activities, described in detail. I think this explains the popularity of magical realism.

The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe opens within the (historical) reality of war, in a house that could easily exist in the real world.

Tip 5: ONE IMPROBABILITY PER STORY

If there are many odd goings-on they should all have, finally, a single cause. That one cause accepted, all the rest follows: the other oddities fall into place.

Sometimes this advice runs to “Writers are allowed one big lie per story”. But there are diversity issues that you can run into if you follow this advice. I fear this particular writing tip might be responsible for all those medieval fantasy worlds which are, when it all boils down, a retrograde white patriarchy. Perhaps writers think that they can only get away with the fantasy world itself, and that every other aspect of politics and 21st century social life must be laid upon this fantastical world otherwise we’re asking too much of readers.

Tip 6: NO UNDERCUTTING YOUR PREMISE

Don’t explain the big event which kicks off the story. Don’t explain it away or make fun of it in any other way, either. (Once you’ve made fun of it, you’re writing comedy, a melodrama killer.)

Melodrama can be ruined in other ways, too. No waking up and it was all a dream.

Tip 7: NO TALKING ABOUT THE IMPROBABILITY IN NARRATIVE SUMMARY

Especially at first, as you’re establishing the event. The improbable events must be shown in scenes rather than explained in narrative summary. Show don’t tell is not always good advice, but it’s good here.

Dialogue is especially useful when showing rather than telling, because well-rendered dialogue feels believable to an audience.

Lampshading has its uses, but be careful how and when you use it.

Tip 8: DON’T LET THE IMPROBABILITY TAKE OVER THE STORY

Write of the improbability sparingly. Don’t let the big weird event become commonplace. The amount of reality versus ‘improbably, magical thing’ has to be balanced. A story in which literally anything can happen is a story in which nothing makes sense.

In Big Love, the situation of the polygamous family living undercover is normal and ordinary 99% of the time, but has the potential to become extraordinary once in a while, which culminates when Bill runs for office. The normal, domestic scenes build credibility and also suspense, since the reader is always waiting for the secret to come out.

In other words, if you’ve got something functioning as a storytelling monster, don’t trot it out in every chapter or the reader will start to yawn. The monsters audiences imagine are more frightening than the monsters they see.

Notes above are from Anson Dibell’s book on writing: Plot and a Draft Zero podcast from Stu and Chas with Stephen Cleary.

MELODRAMA AND CONTAINMENT CULTURE

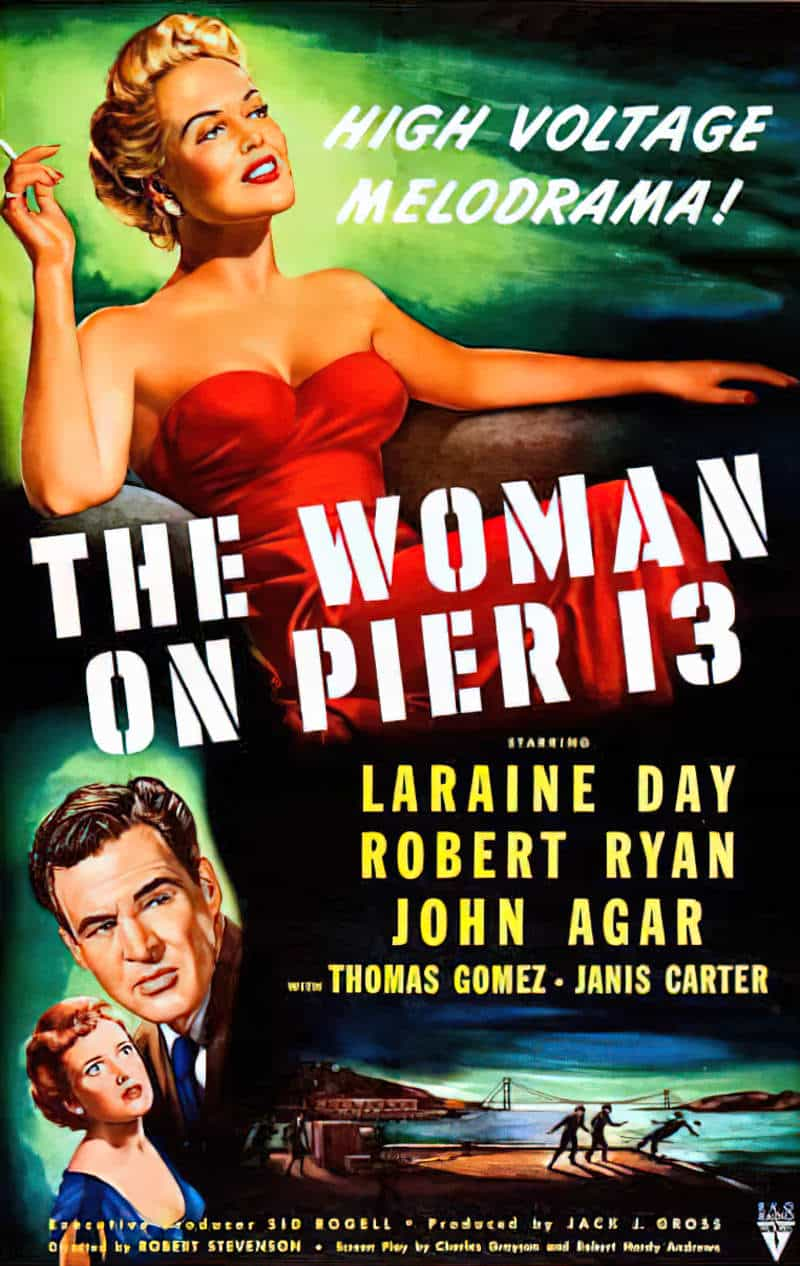

The long 1950s, which extend back to the early postwar period and forward into the early 1960s, were a period of “containment culture” in America, as the media worked to reinforce traditional family values and suspected communist sympathizers were blacklisted from the entertainment industry. Yet some brave filmmakers and actors still challenged the status quo to produce indelible and imaginative work that delivered uncomfortable truths to Cold War audiences.

Triumph Over Containment: American Film in the 1950s (Rutgers University Press, 2021) offers an uncompromising look at some of the era’s greatest films and directors, from household names like Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick to lesser-known iconoclasts like Samuel Fuller and Ida Lupino. Taking in everything from The Thing from Another World (1951) to Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), acclaimed film scholar Robert P. Kolker scours a variety of different genres to find pockets of resistance to the repressive and oppressive norms of Cold War culture. He devotes special attention to two quintessential 1950s genres—the melodrama and the science fiction film—that might seem like polar opposites, but each offered pointed responses to containment culture.

This book takes a fresh look at such directors as Nicholas Ray, John Ford, and Orson Welles, while giving readers a new appreciation for the depth and artistry of 1950s Hollywood films.

New Books Network

RELATED WORD

DUENDE

Duende is a Spanish word to describe a heightened state of emotion, expression and authenticity. Poet Federico García Lorca writes about it at Poetry In Translation.