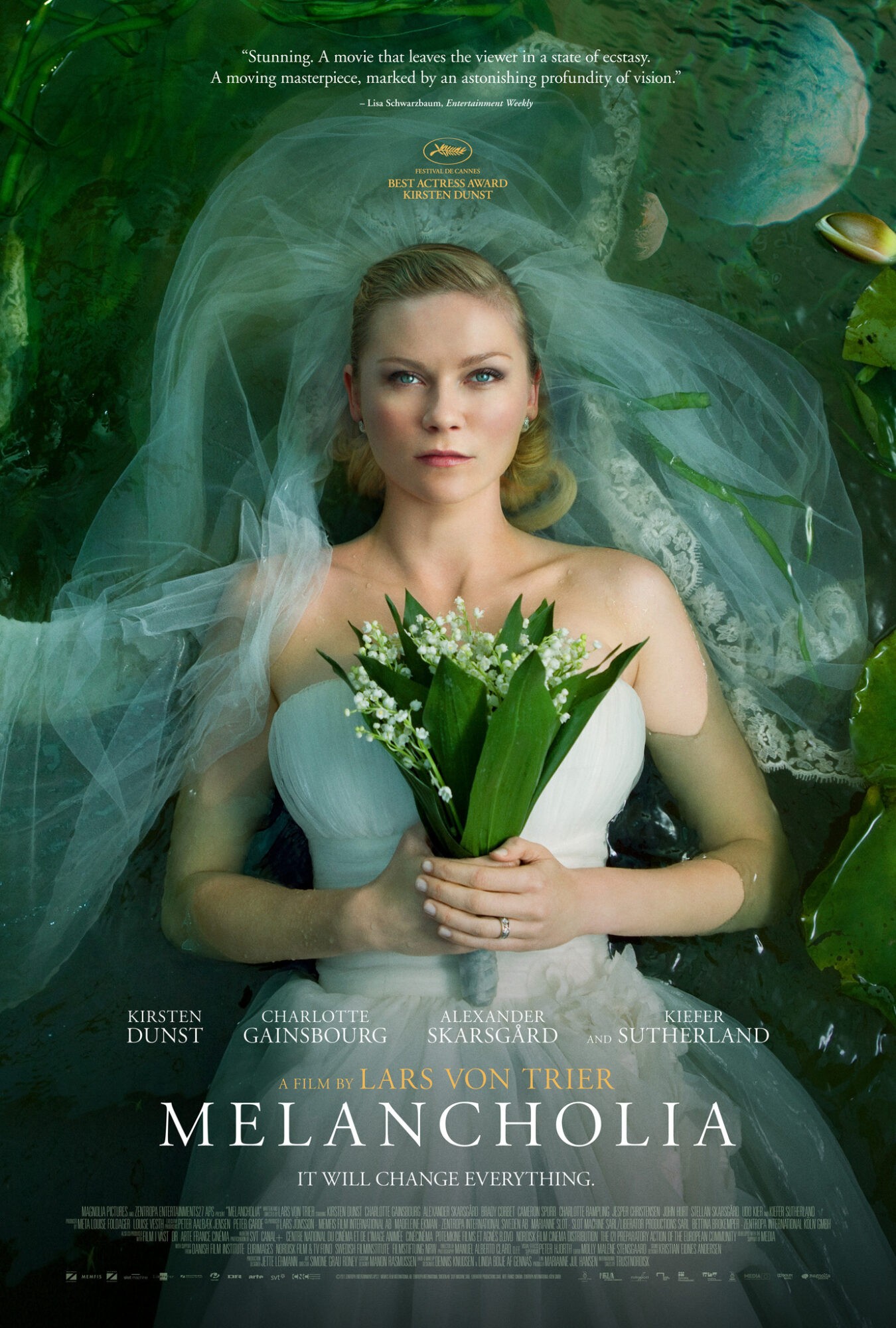

Melancholia is a 2011 film by Lars Von Trier. It’s one of those stories which has variable metaphorical resonance depending on who watches it. The Wizard of Oz and The Little Prince are also like this. We might also read it as an allegory for climate change, or for any other variety of aloneness.

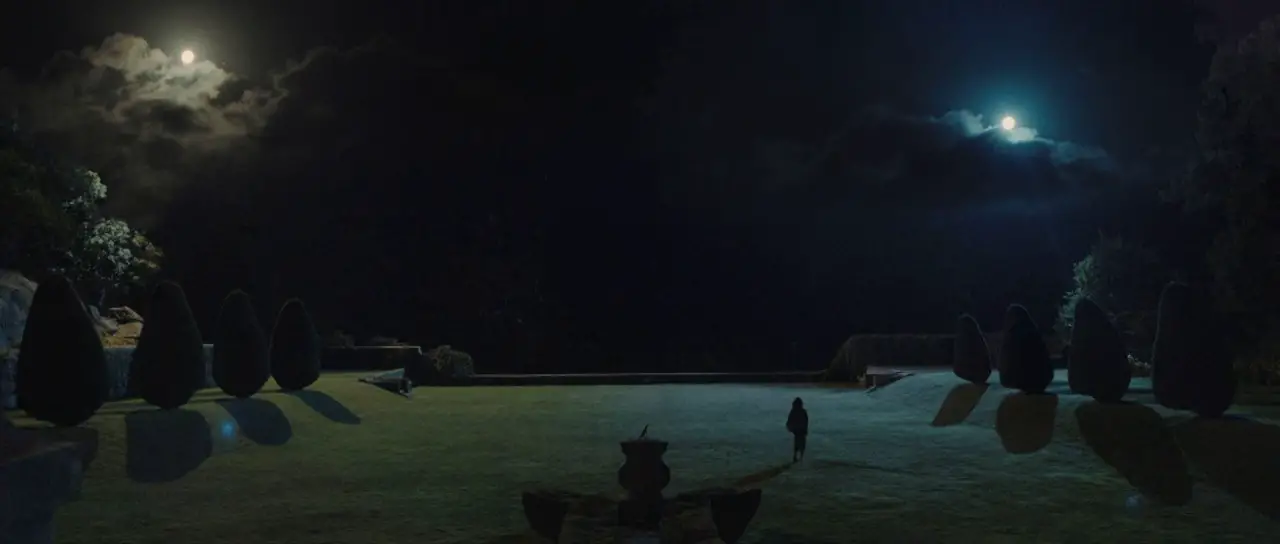

SETTING OF MELANCHOLIA

THE WINDOWS

THE PICTURESQUE AND THE SUBLIME

When talking about description of landscape, we can divide descriptions into two rough groups: Picturesque and Sublime.

THE PICTURESQUE

A peculiar kind of beauty, which is agreeable in a picture

William Gilpin, 1768

Picturesque descriptions reflect the real, objective world of the story. Content and structure are important. Romantic painters mindfully constructed their work to lead the viewer’s eye in a certain way, “from a high viewpoint to a patch of light just below the horizon” (Matthew Brennan, Wordsworth, Turner and, Romantic Landscape, 1987). I’m talking about painters, but Romantic painters influenced how writers depicted landscapes, as well. Think ‘tenderness‘.

Romantic paintings are pretty, but don’t exactly spark imagination in the viewer. By the late 1700s, Romantic painters had had their day. It was time for the age of the Sublime.

THE SUBLIME

A description in sublime mode may start with the picturesque, but then goes further with it. Sublime descriptions are supposed to spark reader imagination and spark a psychological reaction.

The sublime mode has subcategories:

- the sublime in nature (considered primary — the most reliable way to enter a sublime state is to go outside into nature)

- technological

- literary

- painting

What does sublime even mean? Depends on what kind of sublime we’re talking about. In nature, you need grandeur. Think tall mountains, the feeling of enormous sea while standing on a spit. You need wildness. You are so overwhelmed by the experience that you’re living in the moment. Worries lift. You’ll feel part of it but also like you don’t fully understand it, because your perspective is too small. This may even evoke a kind of terror, though not necessarily in a bad way. Try to imagine a positive form of terror. Also, think alienation. You’re all on your own here. I believe this describes Justine’s emotional state towards the end of the film Melancholia.

An artist (or writer) depicting the sublime may mix up the palette to describe a scene, so we can never settle on a single view. Lars Von Trier keeps asking us to look up at the sky. With each look up, the time of day is different. Then a moon appears. Ah, but is it a moon? It’s kinda blue.

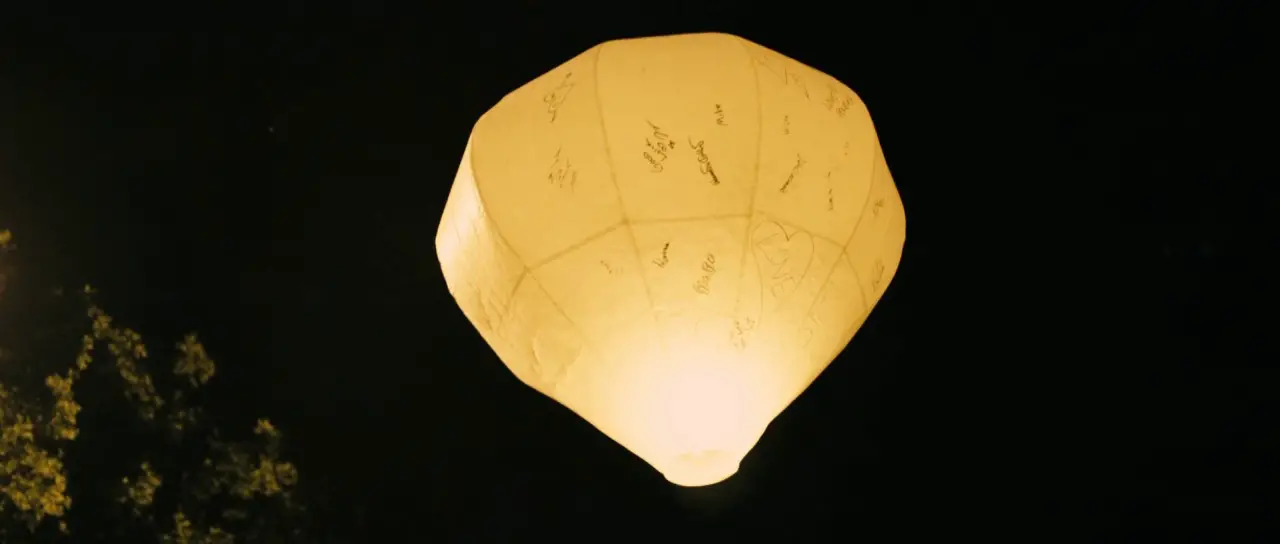

That ain’t no moon. The hot-air balloon sent up as part of the wedding ceremony prefigures the apocalyptic orb of light coming straight for them. We don’t know what’s going on, what we’re meant to be seeing or its significance. This vista is constantly changing, which is unsettling at best, building to terror.

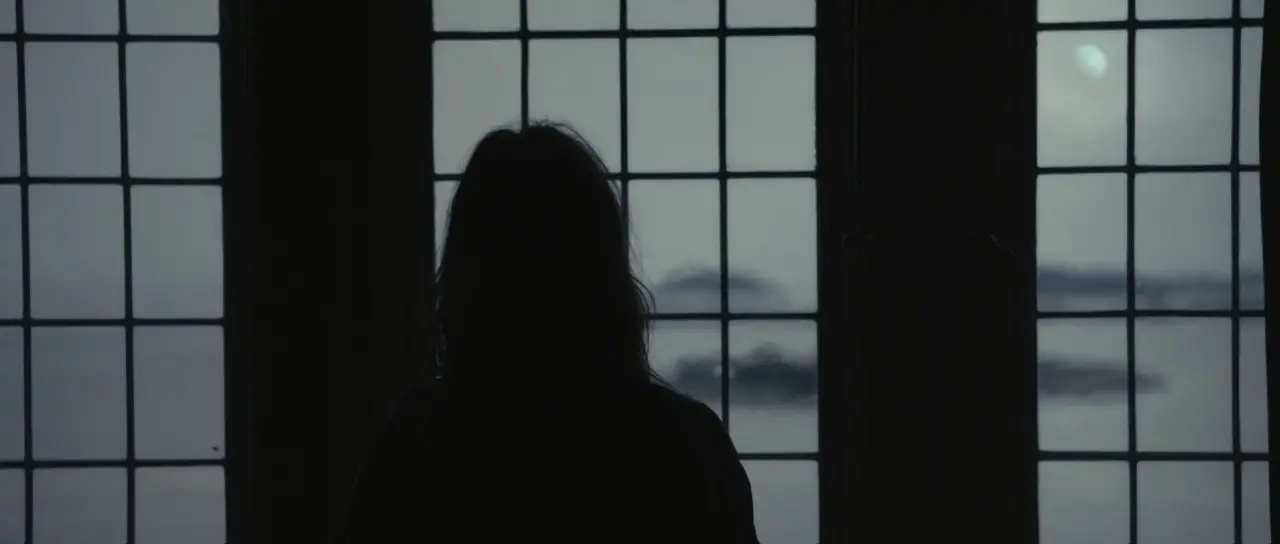

Obviously, when we’re talking about the sublime in art (and literature, and movies) it’ll look a little different. In art, obscurity is key. And text does a better job at obscuring than art or film because writers can literally leave out whatever they want to, whereas an artist or film-maker has to provide a complete picture.

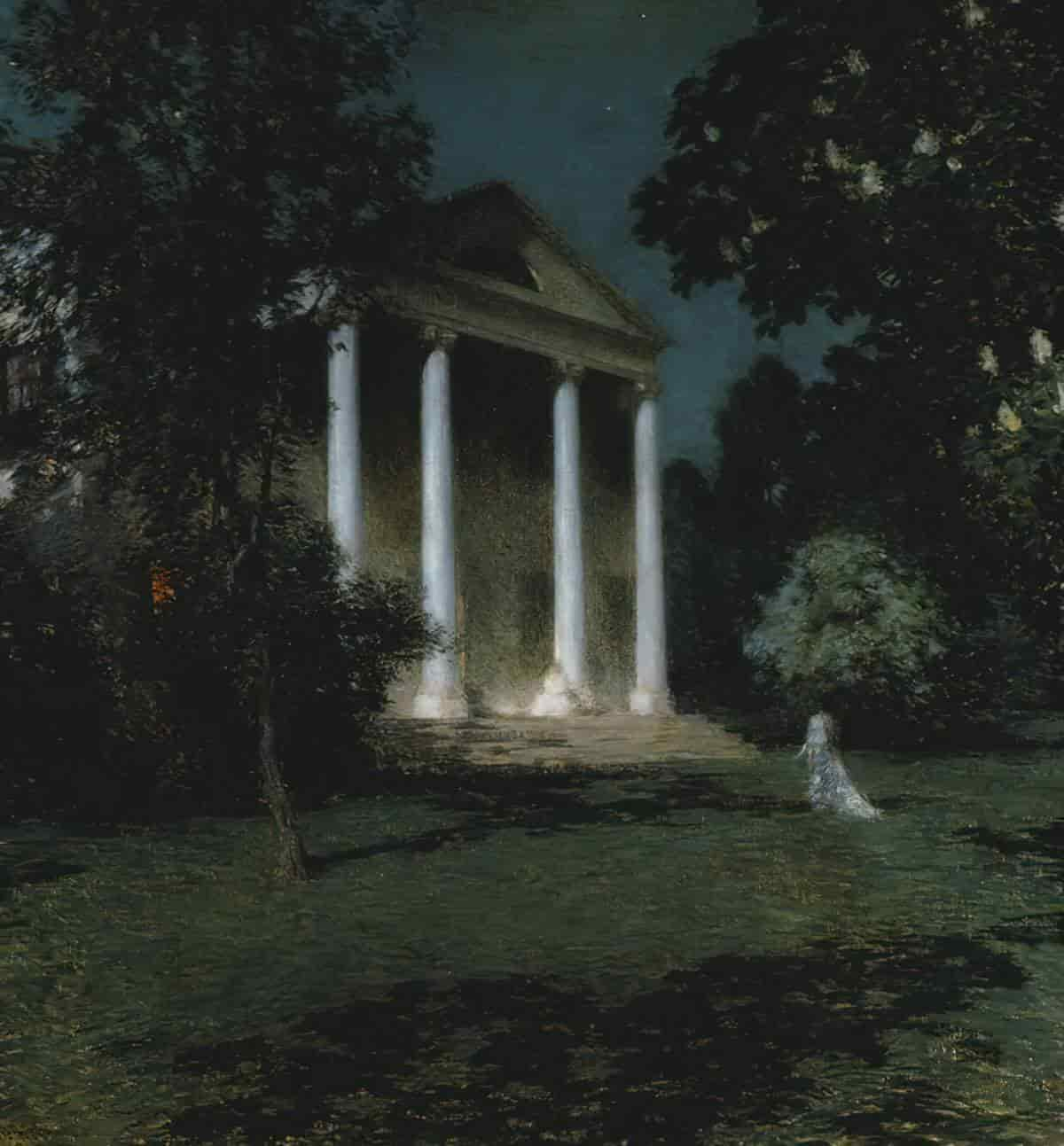

So what can painters and film-makers use? Basically, there’s an emphasis on colour and light, in place of line and form. Ideally, you want the viewer to create for themselves part of what you’re showing them. Whatever’s off the side of the frame (or left out of the story) will create a sense of obscurity, leading viewers into a sublime mindset. By light, we’re talking illumination vs. shadow.

PERIOD — a story’s place in time. Melancholia is a meld of old and new. When storytellers bring old and new together, they’re taking us out of chronos and into mythos, mythic time, where clocks no longer run chronologically. We connect with everything that came before and everything that comes after.

- A classic Gothic mansion, uplit from below like an ominous face.

- All the trappings of a modern luxurious wedding: The limousine, the manicured golf course

Across the history of art, vapour or fog is frequently used to obscure, leading us visually into the sublime.

DURATION — Two days. The wedding and after the wedding

LOCATION — This wedding venue is a heterotopia. It’s easy to imagine the rest of the world in absolute chaos right now.

ARENA — There’s mention of a nearby village, but the story focuses entirely on the characters who remain in this enclosed arena of the luxury venue. This allows for a psychological story rather than something from the action genre.

MANMADE SPACES — Importantly, the house is surrounded by a manicured golf course. Is there anything more fitting? A golf course has the appearance of belonging to nature, but it is the peak example of nature tamed by humans. The turf is a monoculture, sprayed to within an inch of its life. The sand pits are miniaturised deserts or swamps.

NATURAL SETTINGS — Main characters briefly take a trip into what passes for wilderness in this highly manicured setting when they go for a ride through trees on horses.

WEATHER — Fog is significant, as already mentioned. Other than that, the distinction between night and day is more important than any distinction between hot and cold, rainy and sunny.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — The telescope juxtaposed against the crude, wire contraption, which turns out to be pretty darn good at predicting reality.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT — We never learn exactly what’s going on in the wider world of the story but we can deduce chaos.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories. In what way are characters wrong about the veridical world of the story, and how will this be their downfall (or advantage)?

Justine’s tendency towards melancholy serves her well during the apocalypse.

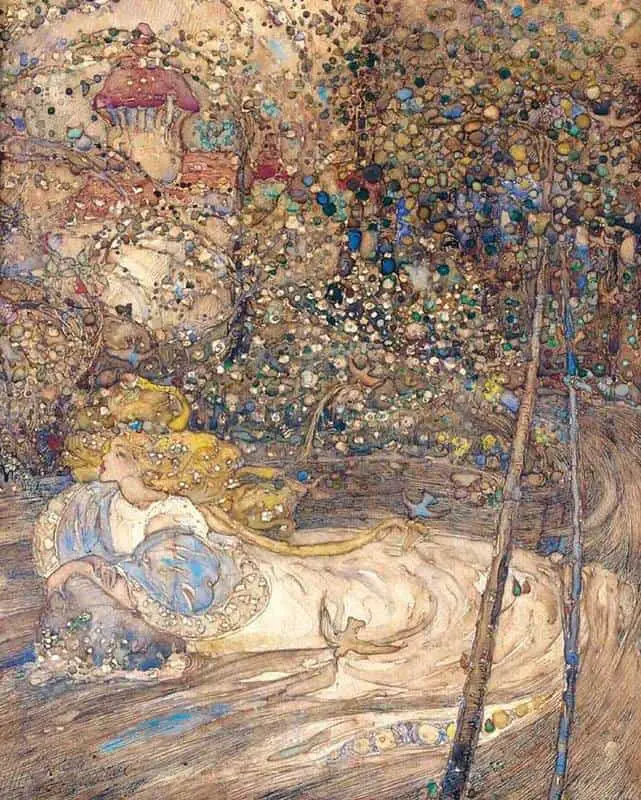

See also: Romantic Portrayals of Death in Painting by the Romanticists: Romanticists were particularly fond of showing the scary yet fascinating topic of death in their romantic paintings from The Collector

Here in Australia, musician Nick Cave used this pose for his song performed with Kylie: “Where The Wild Roses Grow”.

Other images of Ophelia:

STORY STRUCTURE OF MELANCHOLIA

“When I write, I write about myself and she [Justine] gets depression and it’s more or less a description of my own depression,” Von Trier has said about Melancholia. “But I see myself in both of the sisters. So, if you choose to, you can see them as two sides of the one person. That’s how I write.”

The other sister, Claire, is played by Charlotte Gainsbourgh and, as the annihilation of the planet and everything on it draws closer, she becomes more and more fragile as the intelligence and strength that was always part of Justine’s character grows.

Sandy George at SBS

PARATEXT

Two sisters find their already strained relationship challenged as a mysterious new planet threatens to collide with Earth.

Marketing Copy

Marketing copy suggests the film is, at its heart, the story of two sisters who are fighting. I suspect this is because people love the promise of a ‘bitch fight’. For this reason, the British media are constantly trying to drum up conflict between Kate and Meghan. In reality, Melancholia is the story of a community as it faces the end of everything. Films tend to focus on two characters in their marketing rather than on communities. For that same reason, Brokeback Mountain was marketed as a love story between two men, whereas Annie Proulx was very clear: It’s the story of hate in a community.

However, there may be another good reason for focusing on the ‘two’ sisters in the marketing copy of Melancholia. The symbolism of duality undergirds the story.

THE SYMBOLISM OF DUALITY IN MELANCHOLIA

- The two planets (Earth and Melancholia)

- The story is divided into two parts: The Wedding and After the Wedding

- Two sisters (Claire and Justine)

- Marriage between two people (Claire and Michael)

- The structured English garden, in which topiary mirrors itself in neat, ordered rows

- Old and new

- Joy and sadness

- Two dominant colours: Blue and yellow.

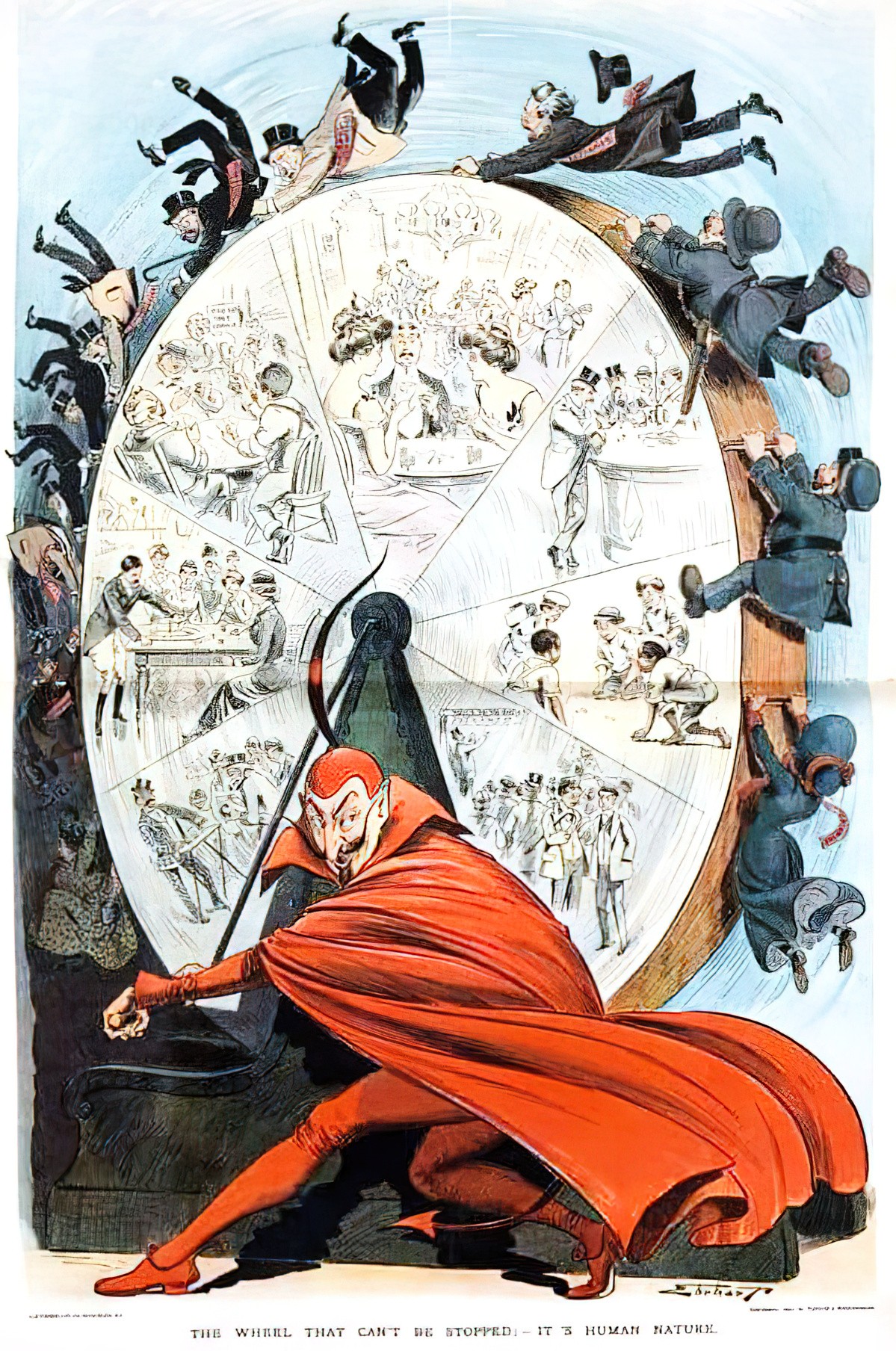

Why the duality of Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia? What’s duality doing for the viewer?

When something in a story world matches a story’s ending, that something prefigures the ending. The effect is a sense of fate. The duality running throughout the wedding on Earth seems to lead everyone, everything along a single, unalterable path towards the destruction of Earth. In the story world, this is absolutely true. Although the characters didn’t know it (for sure), Earth was always in Melancholia’s path. There was always a ticking clock. Duality equals fate.

Note that the theme of fate ties in with the theme of witches i.e. The Three Fates.

Note that in order to make use of the Three Fates alongside the duality thread of the story, the mother (who symbolically makes the third fate) is removed from the story after part one.

SHORTCOMING

Does Justine see what’s coming? Is she basically a visionary? The opening sequence to Melancholia works as a flash-forward at the symbolic level. But they also serve in the present at the symbolic level. There is never a point near the end where Claire carries her son across the golf course as she sinks into the turf. This represents a mental state. Likewise, Justine never drags netting behind her (or whatever that is). That’s her mental state. The long shot of Justine, Justine’s nephew and Claire, each standing apart as if staged in front of the Gothic mansion, is an envisioning of their mental state. At the end of the world they are together, just the three of them, but also completely alone. Death, like birth, can only ever be done in isolation. (Yes, even twins. Your own birth is your own birth.)

It’s tempting to call Justine a Postmodern Cassandra, who sees what’s coming yet no one believes her. But Justine isn’t exactly out and loud about her prophecy. She quietly, grimly plods her way through to the end. She is more like Oedipus in that respect. She knows her own end. But she must endure a process of catharsis, consummating prophecy.

If you see this film as an allegory for depression, you might read Justine like this: Justine has always worried about everything. This has always felt lonely. Even her own family (especially her own family) are on a different wavelength. But now the end of the world is nigh, finally Justine is the normal one. Her doomsday outlook is coming to fruition. While everyone else struggles to cope with impending doom, this is Justine’s normal state — the state where she feels most comfortable. Like someone preparing for suicide, there’s comfort to be derived from knowing there’s no tomorrow.

DESIRE

One thing that is never made clear: The extent to which everyone fears planetary collision. Over the course of the story it does become somewhat clear: The whole world can see this planet heading towards us, but experts have told the masses not to worry because there is only a very small chance that Earth will be impacted.

We can use climate change as a corollary here, though it is inverted: There is a very large chance life on Earth will be impacted by runaway climate change if nothing is done about worldwide emissions. Yet everyone sits with their own level of (dis)comfort on this one. I’m sure in your own life you know people at all points on that spectrum. Some deny outright that climate change is happening; others say it’s cyclical, nothing we can do about it. At the other end of that spectrum are people who find it increasingly difficult to function due to existential* dread.

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

Young people and children are especially vulnerable to this mindset, and I can’t blame them.

So what do the characters in Melancholia want? Reading between the lines, Justine has agreed to marry a man she never had any intention of spending the rest of her life with. Instead, she decided to spend her last few days alive having the best time of her life. What are little girls told is the most important day of their lives? Their wedding day.

What else do people do when they feel the world is ending? On her wedding day, she has sex with someone who is not her husband. Why? This feels like a reclamation of selfhood. She may officially belong to one man on paper, but desires change when an entire married life is compressed into two days. She is seeking the widest variety of pleasure she can, under the circumstances. Even her new husband won’t grieve for long. They’ll all be dead. She needn’t feel excessively guilty about that.

A pre-apocalyptic wedding also gives Justine the chance to commune with her favourite extended family members, notably her nephew, who looks up to her as a source of strength. Justine is the woman for the moment. As someone who regularly lives with a doomsday mindset, Justine has the skills to get him through their final moments alive.

OPPONENT

This is a disaster movie with an existential opponent who doesn’t care a whit about the damage it is about to wreak: The blue planet about to crash into Earth.

ROMANTIC OPPONENT

I find it interesting that other viewers feel deep empathy for Justine’s husband, Michael. (He feels like an unrounded character to me, and I didn’t feel much for him at all.)

Alexander Skarsgard as Michael probably gives my favorite performance in the film; he is totally inside the part as a loving young man who knows he has married a very sensitive woman and is trying to make her happy—and while the film is devoted to exploring her distraction and pain, it is his heartbreak, when he realizes that she does not love him enough, that is most moving.

Offscreen review: Using the Imagination of Disaster as Justification for Misanthropy by Daniel Garrett (2012)

HEAD VERSUS HEART VERSUS GUT

Matt Bird talks about a common character ensemble: Head, Heart, Gut. Once you know of it, you see it everywhere in story. In the trio of Jack, Claire and Justine, Jack is clearly the head. He has a head for business. (Even the English idiom should tell us: heads and businessmen go together.) Out of the sisters, who is the heart and who is the gut? As well as a businessman, Jack is interested in science. Scientists tell him everything’s going to be okay, and he believes them.

Kiefer Sutherland, as Claire’s husband John, as Justine and Michael’s brother-in-law, has a dry delivery that is knowing and funny (and while this part is very different from the amoral government agent and man of action that Sutherland played in the television program 24, part of a viewer’s comfort with him depends on that familiarity).

Offscreen review: Using the Imagination of Disaster as Justification for Misanthropy by Daniel Garrett (2012)

I’d say Claire is the heart. If Jack weren’t there as a contrast character I’d say she were the head, but over the course of the film she tries to bring disparate personalities together.

Claire is ultimately about building community. Claire’s husband (the head character) believes scientists over the make-shift contraption utilised by Claire — the ring of wire which tells her the planet is getting closer. This ring definitely plays into the witch symbolism attached to each of the three women in Justine’s family. Even the number three is significant in witchcraft. Goddess triads are common in Classical mythology. Think also of Macbeth, The Three Witches of Ben Johnson etc.

The gut character often eats a lot (especially in comedy) but this is frequently replaced by an appetite for sex in stories for adults. Justine shows her sexual appetite more than her appetite for food. (I have no reason to believe she has an indiscriminate sexual appetite outside the bounds of this story. I believe, for her, sex on the golf course is a setting-specific coping mechanism.)

UNLOVING WITCH-MOTHER

Justine and Claire’s mother is no fan of marriage, having lost faith in the institution years ago. When she gives an anti-toast to the bride and groom, she’s basically casting a curse upon the marriage, which calls to mind the wicked fairy of “Sleeping Beauty“. Though the curse character of “Sleeping Beauty” happens to be a fairy, fairy tales more generally have a long history of linking mothers with witches. The history of Hansel and Gretel is a good case in point, and Anthony Browne literalised the association in his Postmodern picture book.

As far as hate sink characters go, Gaby is up there alongside Jack.

PLAN

In many stories, the idea that one decision leads fatally into an entire raft of unintended consequences comes in for intense scrutiny. A collection of random examples, based on what comes to mind:

- “The Frog Princess” is also about marriage. What happens if a young woman turns down an offer of marriage?

- “Rosamund and the Purple Jar” is a girl’s coming-of-age story. What happens if Rosamund insists on owning something without substance?

- Pig The Pug by Aaron Blabey. What happens to you if you refuse to share your toys?

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. What happens if you judge someone before really getting to know them?

Melancholia has none of that. There’s no moral decision to be made which will affect the outcome. There is literally nothing anything anyone can do in this scenario, except prepare psychologically for the end. Since death comes for us all eventually, Melancholia is a universal story. We spend our whole lives preparing for death.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Each character deals with the End in their own way.

Jack eventually realises the scientists were wrong. He would rather kill himself in private than face he was wrong to the women in his life.

Meanwhile, Justine guides her sister and nephew through this last few days of their lives because she was made for this moment.

ANAGNORISIS

This story has an external anagnorisis and an internal, psychological one.

External Revelation: Melancholia will be hitting Earth after all. Everyone is about to die. We know this moment because John kills himself.

Internal Revelation: It is time to prepare for the end. Justine is the best at this, which is why the movie focuses on her.

What does anagnorisis look like on screen?

NEW SITUATION

Well.

RESONANCE

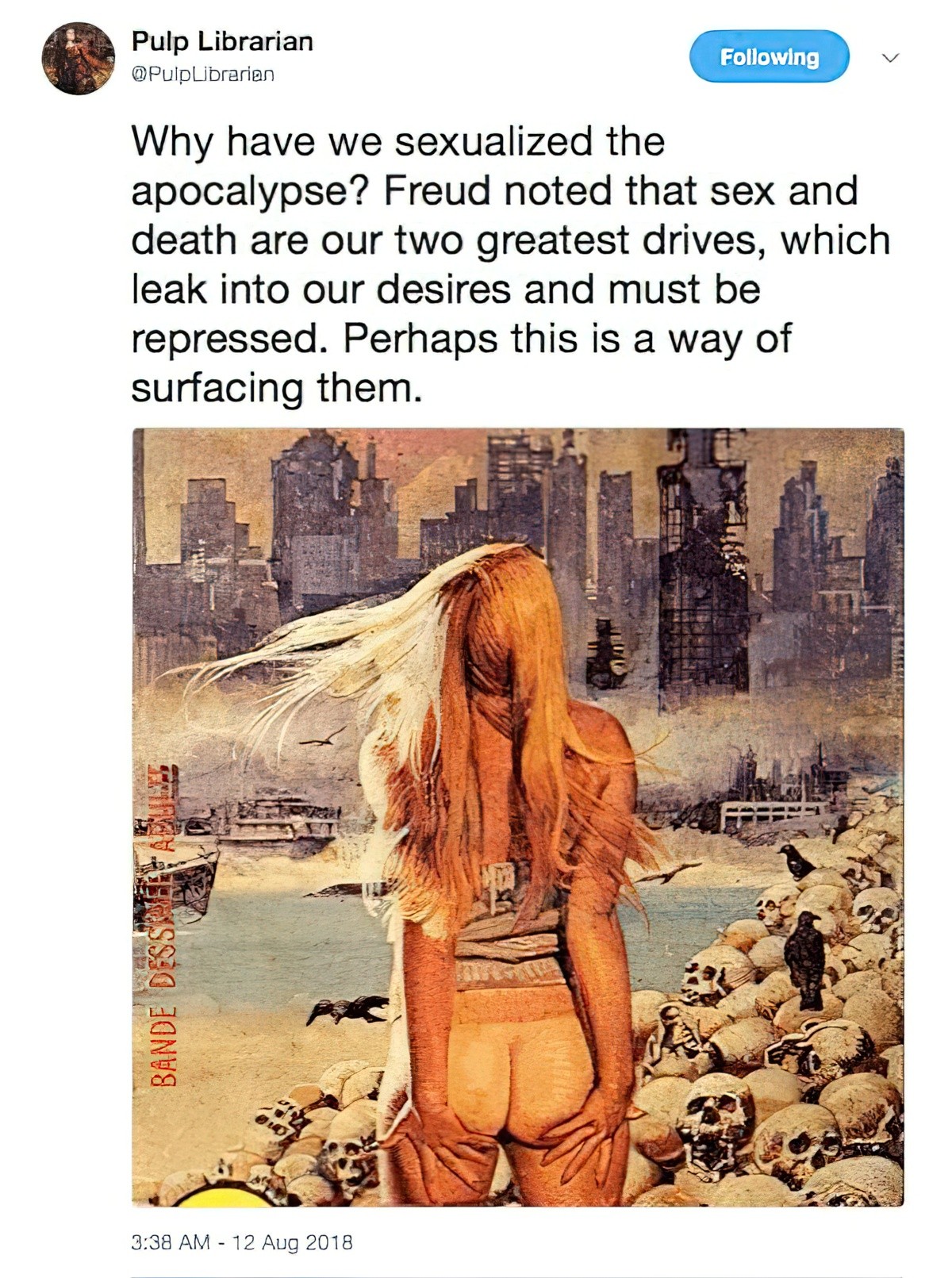

THE SEXUALISATION OF APOCALYPSE

I am weary of apocalypse stories, and not because it feels like we’re living in an apocalypse right now. (Also true.) So often they take communities back to an idealised (never true) 1950s version of humanity, in which men and women divide into separate tribes-within-tribes. Stories enact a masculine fantasy about saving the world and protecting their women.

Dystopian stories for adults feel mostly pitched at men, which is probably why the apocalypse has become sexualised. We might also go the Freudian route:

But Melancholia is a little different. This is not a sexual male fantasy at all. In fact, the designated hot guy (played by Alexander Sarsgard) disappears before the mid-point, because he never was the point. When Justine offers herself naked next to the river, she is making herself one with the universe in mental preparation for oblivion. This scene calls to mind witch rituals of yore. Throughout history, witches have been the most persecuted minorities, which also makes for powerful reclamation.

SHIRLEY JACKSON’S THE SUNDIAL

For an interesting compare and contrast, check out The Sundial by Shirley Jackson (1958). In Jackson’s novel, Aunt Fanny knows when the world will end….

Aunt Fanny has always been somewhat peculiar. No one is surprised that while the Halloran clan gathers at the crumbling old mansion for a funeral she wanders off to the secret garden. But when she reports the vision she had there, the family is engulfed in fear, violence, and madness. For Aunt Fanny’s long-dead father has given her the precise date of the final cataclysm!

MARKETING COPY FOR “THE SUNDIAL”

Jackson uses the end of the world imagery to create comfort for the wealthy family. They are not put off by the world ending, as Eggener writes of the romantic sublime’s attachment to parsing out the wealthy against the common. While there is a sense of subversion of the “ideals of domestic tranquillity and security,” it is not at the villager level—the Hallorans are the ones who ultimately take the world’s overall decay in stride. Their reaction is to protect themselves and their established order inside the mansion’s walls, creating happy domesticity by selection and compartmentalization of their existing rooms that will one day be worshipped, not by the outsiders, but by the chosen ones with particular objects of importance. Their space is the chosen space, their rules and regulations are enforced from the inside out.

“Homespun” Horror: Shirley Jackson’s Domestic Doubling by Hannah Phillips

FURTHER READING

Melancholy and the Landscape: Locating Sadness, Memory, and Reflection in the Landscape (Routledge, 2018)

Written as an advocacy of melancholy’s value as part of the landscape experience, Melancholy and the Landscape: Locating Sadness, Memory, and Reflection in the Landscape (Routledge, 2018) situates the concept within landscape’s aesthetic traditions, and reveals how it is a critical part of ethics and empath. With a history that extends back to ancient times, melancholy has hovered at the edges of the appreciation of landscape, including the aesthetic exertions of the 18th century. Implicated in the more formal categories of the sublime and the picturesque, melancholy captures the subtle condition of beautiful sadness.

interview at New Books Network

In this episode of High Theory, Laura Stokes talks about melancholy. One of the four humors in ancient humoral medicine, melancholy, or black bile, is a fluid substance and spiritual principle that was thought to move within the human body. A proper quantity of black bile allows one to be calm and contemplative, thoughtful and withdrawn. A superabundance produces sadness, indigestion, and a host of other evils. Research is a melancholy practice; scholars are prone to melancholic dispositions.

High Theory Podcast