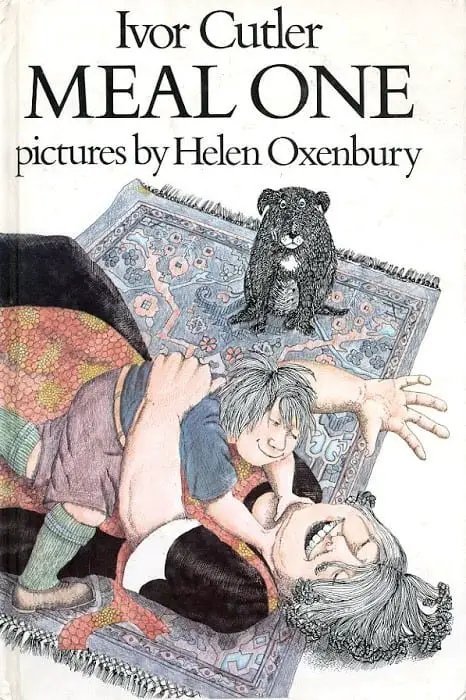

Meal One is a picture book written by Ivor Cutler, Illustrated by Helen Oxenbury, first published 1971.

I maintain you can tell if a picture book illustrator has a background in costume or set design. Likewise, you can tell if they have an animation background or a graphic design background. You can tell if they have kids in their lives and you can tell if they are an established ‘humorist’.

Ivor Cutler (1923-2006) was a humorist who, like Spike Milligan, created many things for adult enjoyment and sometimes also for kids. Like Julia Donaldson he was a singer and songwriter, though he did not challenge himself with rhyme in this particular story. (There’s often no need.)

In line with the majority of picture books created by humorists, Meal One has a crackers plot. Cutler’s obituary in The Guardian described him as an ‘unassuming master of offbeat humour whose eccentric take on the world entertained generations’.

At its heart Meal One is a playful carnivalesque story, with a ‘fun mum’ who has a childlike involvement in her son’s life. Reading this story, I’m reminded how very rare that is, even by today’s standards, in which the mother or girl is so often ‘the mature one’, the ‘example setting’ and ‘swotty’ one. If a parent is fun, it’s almost always the dad, though more likely a grandparent. The fun mother of this story is something I really appreciate about this picture book, even though I would never let my own kid dig a hole in the floor of the house as part of play.

Cutler was himself a non-mainstream parent. A line from his obituary tells us he ‘married and had two children, although the marriage did not last, and elements of his eccentric behaviour surfaced in his parenting, such as his insistence on sending his son to his first day at school in a kilt.’ Back in those days, a boy wearing a kilt was a terrible, terrible thing. This speaks admirably to his forward-looking gender transgression and open-mindedness.

SETTING OF MEAL ONE

This is a Scottish book, best read by someone in a Scottish accent, though it could equally be read in a South Island New Zealand accent, where ‘wee’ is commonly used. Writers with non-mainstream regional dialects are at an advantage when writing humour, I find, because the dialect itself becomes part of the humour.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MEAL ONE

PARATEXT

Helbert and his mother like doing a lot of things together, but their experiment with a plum stone gets out of hand.

marketing copy

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF MEAL ONE

An Every Child is at home

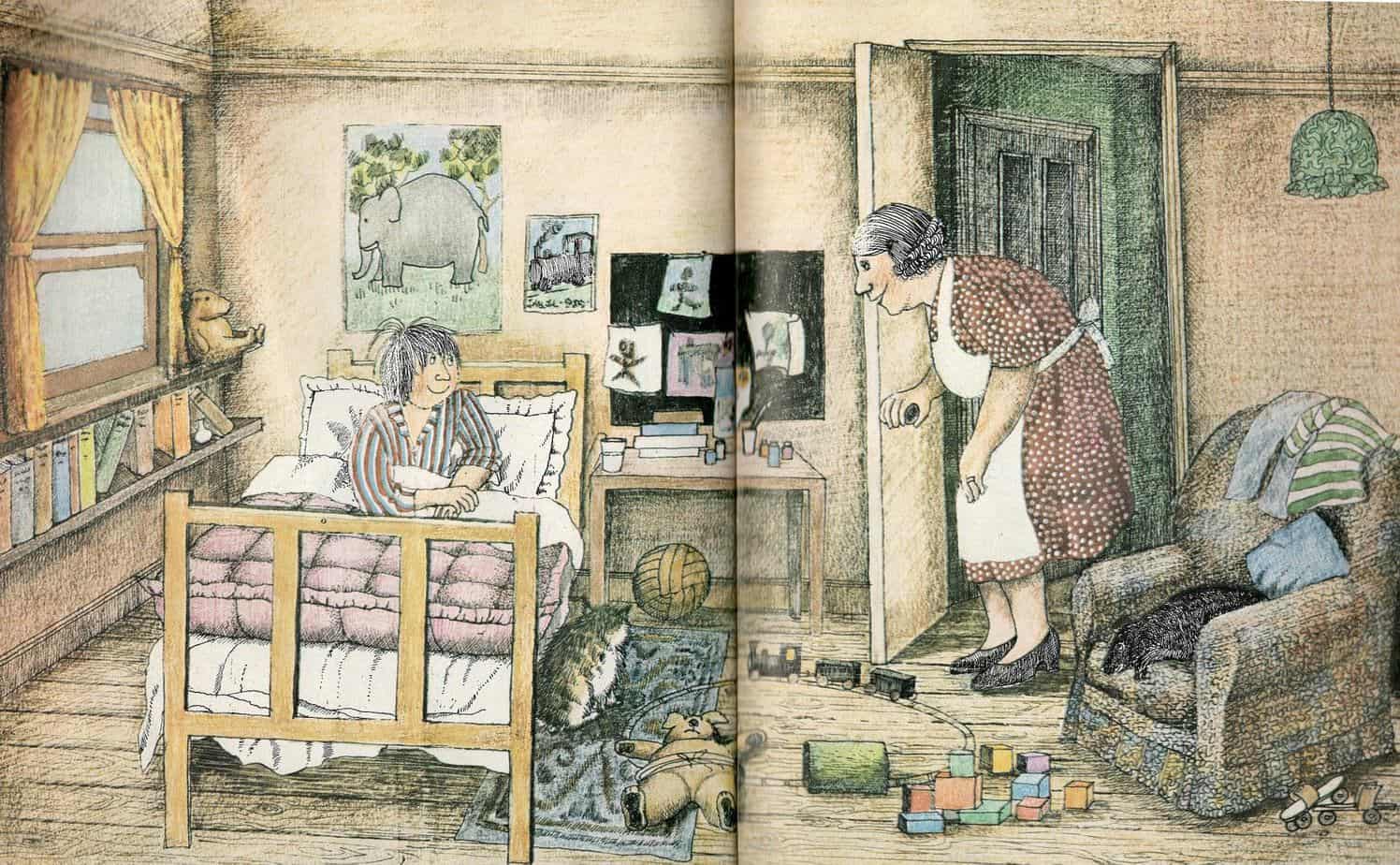

A boy, called Helbert wakes up in bed and something is unusual. This reminds me of The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka. In this case, it is simply that a plum has been put into the boy’s mouth.

I’m not sure how many young readers would be familiar with the idiomatic expression ‘to have a plum in one’s mouth’, but for adult co-readers, this affords the opportunity to play with voice and accent while reading the story aloud.

(Apart from his name, Helbert McHerbert is indistinguishable from any boy who might star in a story.)

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

“Who put it in my mouth?” Halbert wondered.

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

Before he even has time to wake up properly, the mother pokes her head out from under the bed. A marvellous inversion of how mothers in picture books are almost always comforting children who think a monster lives under the bed.

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

There is no hierarchy between mother and son; they are equals in play. This is unusual, even for a carnivalesque picture book. Usually the parent is ‘parent-like’, and exists to contrast with a carnivalesque stranger who turns up out of the blue, Cat In The Hat style.

Fun builds!

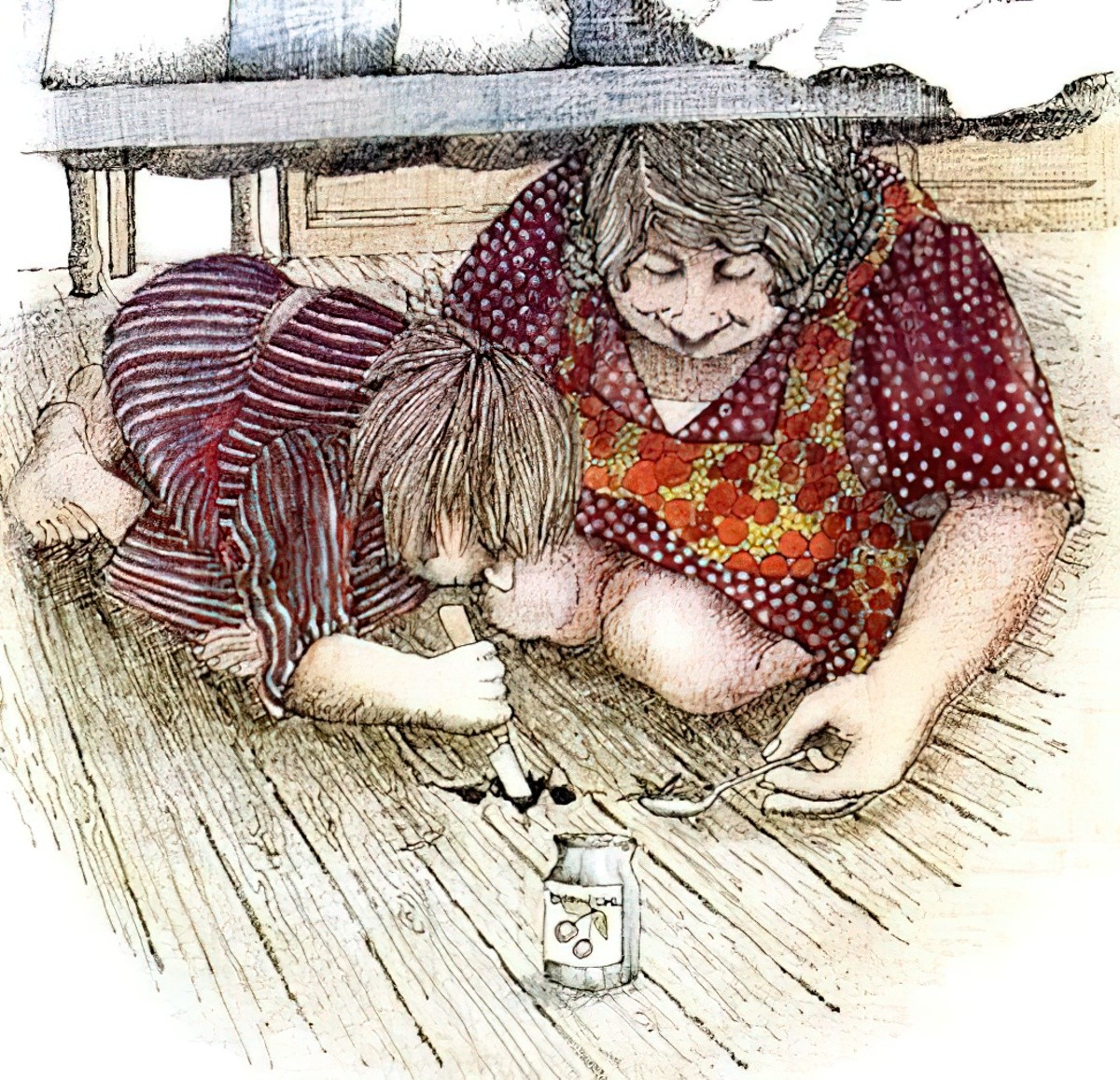

Halbert and his mum were great pals. They played football, and fighting, and ate fish and chips with their fingers. Pickled onions, too. They dug holes.

Peak Fun!

After listing a succession of slightly surprising ways to have fun (play fighting with your mum?) the story takes on a surrealist turn. Halbert eats the plum, digs a hole in the floor under his bed and plants the stone.

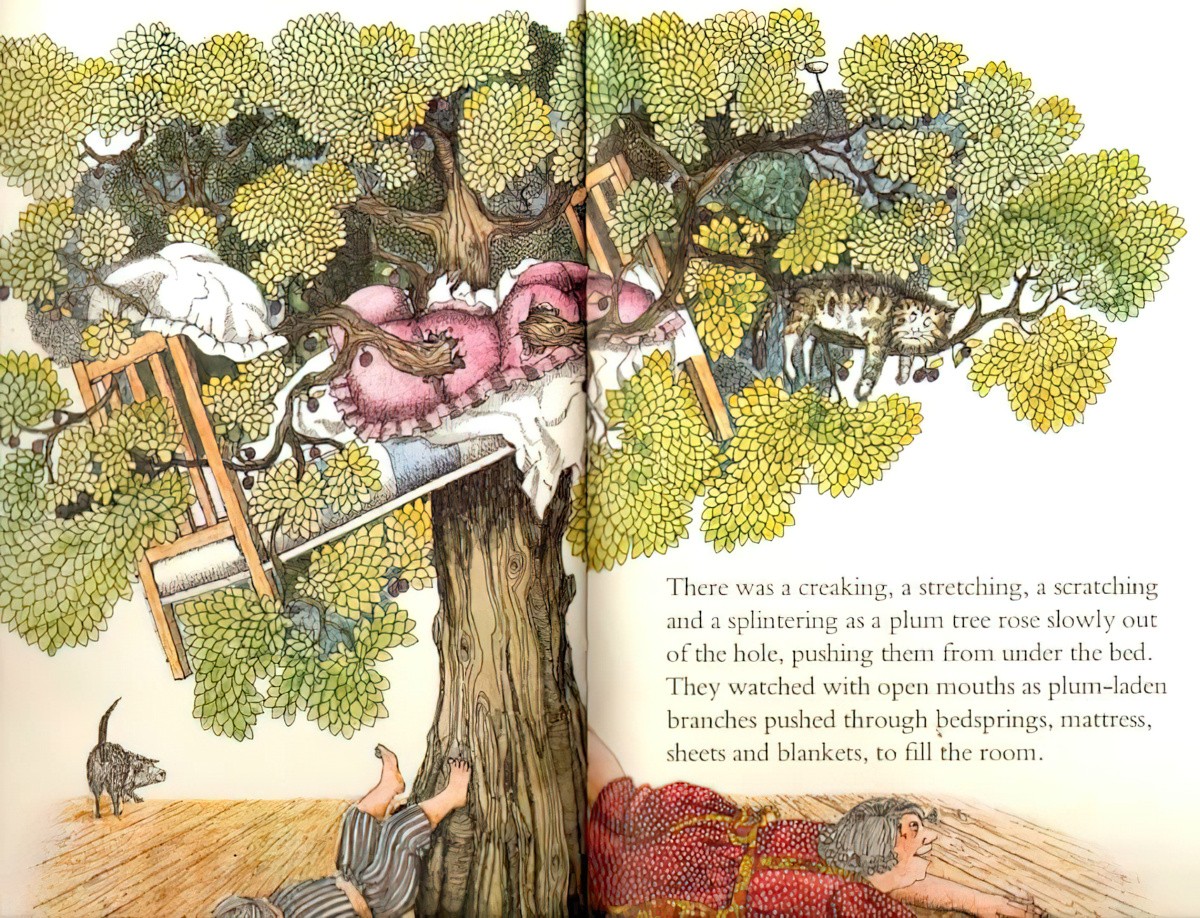

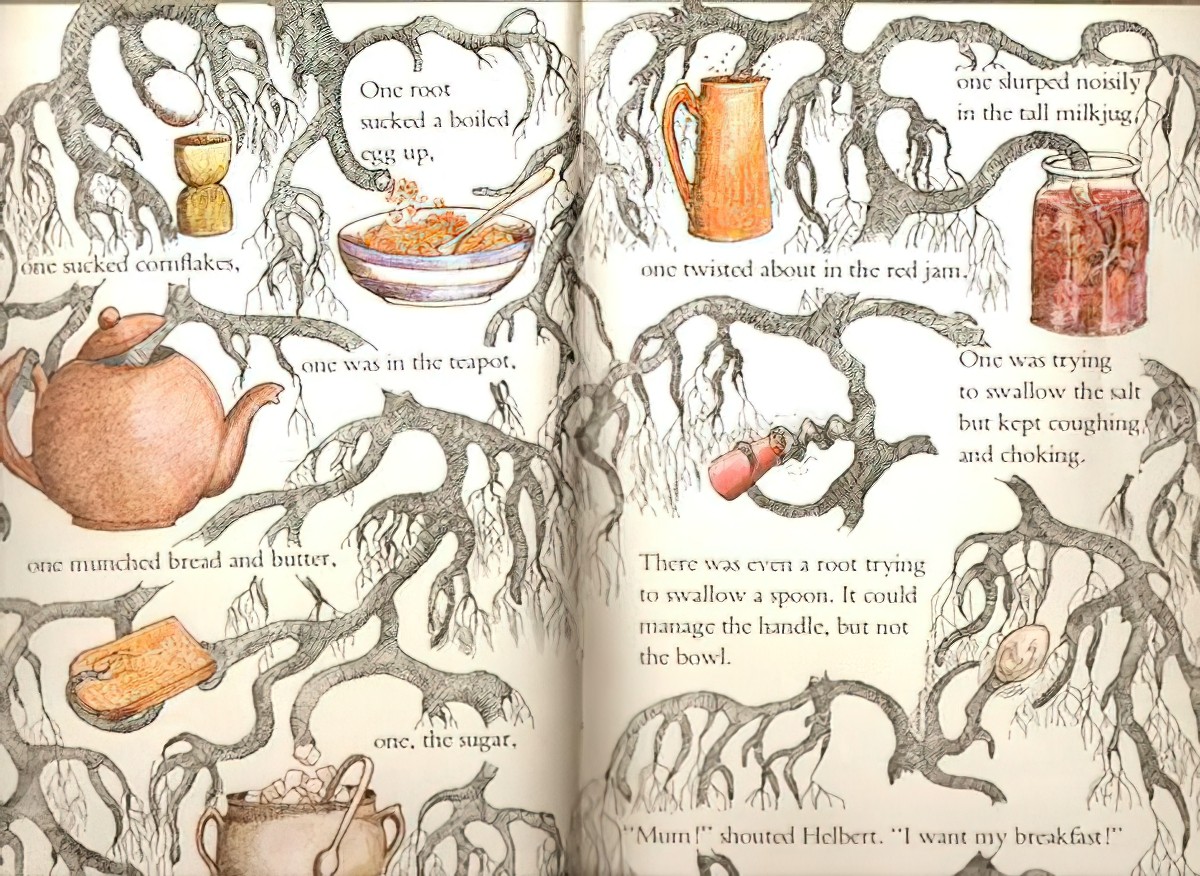

Next the story turns a bit Jack and the Beanstalk. We know what’s going to happen. A giant tree grows overnight, pushing the bed up onto its branches. Oliver Jeffers uses similar imagery in Stuck! Things stuck in trees, especially kites and cats, are a constant visual gag in children’s stories. Sure enough there’s a cat stuck in this tree as well. Helen Oxenbury depicts the cat rolling its eyes, as if in resignation. If cats had eyeballs like ours, I’m sure they would be rolling them constantly.

This is a comically inverted tree. As established by the opening of the plum, trees normally bear fruit and provide us with food. But this tree does the opposite; this tree gobbles up all their food!

Notice how this inversion begins a little earlier, with Halbert nodding his head (meaning yes) while saying ‘no’, there’s nothing happening down there. (In fact the stone is sprouting.)

Return to the Home state

This particular tale starts returning the young reader to the home state earlier than most stories, which are simply bookeneded with the reassurance of motherly adults.

Halbert’s mother starts to return to a more motherly demeanour when she expresses concern about where Halbert will sleep now that the bed is stuck in the tree. Mischievously, Halbert declares he will sleep in the tree. “Does that answer your question, Mum?!”

The mother becomes more mother-like again when she orders him down from the tree for what she bizarrely calls ‘Meal One’. This is also the title of the book, and I have no idea about the cultural context. Is there any wider-world context for this phrase? Or does she simply mean ‘the first meal of the rest of your life, post fantasy’?

This article tells us all about how the word ‘meal’ is used in Scottish dialect, but says nothing about ‘meal one’. Or maybe she just means first meal of the day? Is this Cutler’s personal word for ‘breakfast’?

The mother becomes more and more reassuringly motherly as she kisses her son’s scratches better and then she even puts his shirt on for him, despite him seeming old enough to do this himself. She then piggybacks him to the kitchen, where the rest of the peak fun ensues.

Why has Cutler decided to return the mother to a reassuring motherly state earlier than in most carnivalesque comedies for young children? Because the mother and the prankster are one and the same character. The child reader enjoys fun, but also needs to enjoy the reassuring presence of a parent who is not altogether off their rocker, but caring.

Peak Fun continues…

This is where the tree is eating up their breakfast. The mother now sees what the boy sees. Adults who finally see the fantasy their child has already seen are fairly common, as are stories in which the adult never sees it at all. An example where the mother doesn’t believe her young son until given the fright of her life is It’s The Bear! by Jez Alborough.

This wacky part of the story is an example of cryptobotany, a feature of Gothic Horror. The subgenre of cryptobotany was pioneered by Phil Robinson who wrote “The Man Eating Tree” in 1881.

Another example is “The Story of the Grey House“. Guests stay at a secluded country mansion but are strangled and drained of blood by a demoniacal creeper growing among the shrubbery.

See also “The Purple Terror“, written in 1899 by Fred M. White.

Return To Normality

There’s now a record scratch and the story returns to the original waking up scene, but this time there is no plum in the child’s mouth. Comedically, Halbert asks who didn’t put a plum in his mouth. The mother joins in this minor fun by saying, “Me!” She then piggybacks him downstairs to breakfast.

The reader may well wonder if this entire adventure was a dream. Almost any carnivalesque story can be read in this way, perhaps especially surrealist ones like this, where one strange and disconnected thing happens after another.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

This is why I’m not all that motivated to discover if there’s any history behind the phrase ‘Meal One’ as an alternative to ‘breakfast’. I have no real reason to conclude it’s anything other than Cutler’s own idiolect.

If you enjoyed this story, you’ll probably enjoy the picture books of Robert Munsch. Alongside relatively logical stories such as the classic Paperbag Princess he also writes madcap stories such as Aaron’s Hair.